One Hundred Years after Japan’s Forced Annexation of Korea: History and Tasks

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Chapter I: Agendas relating to the Forced Annexation of Korea by Japan

- The Choshu Faction’s Invasion of Korea: Violation of Law and Morality

- Korea-Japan Relations in Modern Times and the Annexation of Korea: An Assessment of the Response to Japan during the Korean Empire Era

- The Russo-Japanese War and Japan’s Annexation of Korea: Considering the “Russia” Factor

- Commander-in-Chief of Staff Otani Kikuzo of the Japanese Army Stationed in Korea During the Pre- and Post-Eulsa Protectorate Treaty Periods

- Typology of the Protectorate

- Chapter II: Colonialism in East Asia and Japan

- Disorder of East Asia and Colonialism

- Observation of Colonial Rule during the Period of Japanization: Focusing on the Loyalty Oath of Imperial Subjects

- Japan’s Colonial Rule of Korea and the Response of the Korean People

- Japan’s Aggression in Northeast China and the Concept of the Inseparability of Manchuria and Korea: Yamagata Aritomo’s Policy Plan

- The Formation of “The Crowd” in Colonial Taiwan: A Study from the Perspective of Historical Sociology

- Chapter III: Illegality and Invalid of Japan’s Annexation of Korea

- Towards Recognition of the Crime of Colonialism: The Lesson of Japan’s Violent Annexation of Korea

- The Liquidation of History in East Asia

- Reexamination of the 1910 Treaty of Japan’s Annexation of Korea from the Viewpoint of Historical Justice and International Law

- Reassessing the Japanese Annexation of Korea from the Perspective of International Law: The Illegality of the Annexation and the “1965 Korea-Japan Claims Settlement Agreement”

- Chapter IV: Historical Perception and Remaining Tasks

- The One Hundredth Anniversary of Japan’s Forced Annexation of Korea and Korean Residents in Japan

- Repentance for Past Misdeeds and Choice for the Future

- Creating a Framework for Dialogue on East Asian Historical Issues

- The Republic of Korea-Japan Agreement and Remaining Challenges

- An Act of War: The U.S. Seizure of Hawai’i

- Chapter V: Historical Justice and Awareness of Reconciliation

- Joint Statement by Korean and Japanese Intellectuals: 1910 Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty Is Null and Void (Full Text)

← 20 | 21 → Chapter I: Agendas relating to the Forced Annexation of Korea by Japan← 21 | 22 →

← 22 | 23 → The Choshu Faction’s Invasion of Korea: Violation of Law and Morality

Professor Emeritus, Seoul National University

1.Introduction

The view that Japan’s colonization of Korea was inevitable because Japan was an outstanding student at adapting modern Western civilization whereas Chosun (the Great Han Empire) was not, is still widely accepted in both countries. This interpretation of history is the basis for the common Japanese belief that the annexation of Korea was legal. Colonial modernization theory has been revived recently in the guise of “objective historiography.”

In fact, Japan’s proactive acceptance of Western civilization following the Meiji Restoration enabled it to modernize more quickly than Korea. It is also true that later on when Chosun started to accept modern Western culture, it requested Japanese assistance. However, the idea that Chosun civilization was backward is a creation of the Japanese people or government, which denied the will of Koreans for enlightenment. The Treaty of Kanghwa, Korea’s first modern act of international relations, was said to be the result of Japan’s endowment. Japan’s propaganda portrayed the Sino-Japanese War the struggle of civilization to expel barbarianism. The “internal reforms” demanded by Japan at the time of this war were undoubtedly an intervention in domestic affairs, yet were praised as necessary for civilizing the savages. A more serious problem is that Japan’s claim to a civilizing mission served as justification for illegal activities and crimes against humanity that occurred during its seizure of Chosun’s national sovereignty. A critical understanding of this history is necessary for correcting the erroneous view that Japan legally annexed Korea.

A more general set of ideas about imperialism supported the perception that Japan’s early modernization led to its colonization of Korea. This view validates Japan’s appropriation of Korea’s national sovereignty on the grounds that such action was a general trend during the era of imperialism. Despite its popularity, this thinking ignores the history of Korea-Japan relations. Soon after the Meiji Restoration, Japan proclaimed invasion of Chosun/the Great Han Empire as its national goal, naming it Seikanron (case for conquering Korea). Even admirers of the Meiji Restoration do not dispute that Japanese imperialism began at this time with the appropriation of ← 23 | 24 → Korean national sovereignty. Japan’s invasion and rule over Korea aligned with Japan’s samurai culture that cultivated expansionism; it was not a byproduct of Western imperialism. Perhaps this is why Japan, unlike Western powers, does not sincerely apologize to its former colonies.

2.The Reality of “Seikanron”: Premodern Expansionism

The defeat of the Western Army of the late Toyotomi Hideyoshi at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 inaugurated the era of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Mori Terumoto was Commander of the Western Army and was based in Hiroshima. Ieyasu became Shogun after the battle and restructured the roughly two hundred daimyos that formed the Bakufu ruling system into three groups. The daimyo related to the Tokugawa family were called Shinpan, those associated with the Eastern Army were known as Fudai, and those belonging to the Western Army became Tozama daimyo. The Shogun led Bakufu politics, involving Shinpan and Fudai but largely excluding Tozama out of retribution. Commander Mori of the Western Army was exiled to the remote area of Hagi and his economic base of 1,300,000 koku was reduced to 370,000 koku. This was the beginning of Choshu Han during the Tokugawa era. Shimazu of Satsuma, who also belonged to the Western Army, fared better as he was able to remain at his home base of Kagoshima and kept 730,000 koku. Political alienation of the Tozama domains fuelled animosity. Thus, when the arrival of Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships” stirred up political unrest 250 years later, the three Tozama forces of Choshu, Satsuma, and Tosa led the movement to overthrow the Tokugawa Bakufu.

The most important task during the last days of the Bakufu was dealing with Perry’s demand to open Japan to trade. The Bakufu were not at all ready when Commodore Perry’s fleet arrived; thus they sought advice from everyone – including the Tozama daimyo. This action was considered the first time the Bakufu stepped outside of “the privacy of Tokugawa” and inquired into “the public world.” However, a new study on the Bakufu’s response to Perry’s arrival and demand to open Japan suggests otherwise. This may signify the likelihood that previous conceptions were rooted in anti-Bakufu sentiment. According to this research, since 1842 the Bakufu leadership received “Oranda Betsudan Fusetsu Gaki (Extra News Reports),” annual intelligence reports from Holland on important events in the West. Thus in 1850, they were well aware that Perry’s fleet departed from Norfolk and was due to reach Japan after stopping in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Okinawa. It was recently discovered that after obtaining this crucial information about Perry’s fleet, the Bakufu leadership signed the treaty as a proactive measure for maintaining their rule. They were fully prepared in ← 24 | 25 → advance of Perry’s arrival; they sent delegates to Uraga to welcome the fleet when it arrived.1

As is widely known, the slogan of the anti-Bakufu forces was “Sonno Joi” (Revere the Emperor and expel the barbarians). Expelling the West can be seen as a closed-door policy, contrary to accepting Western civilization. Although it might be effective for uniting the nation against the invaders, it is possible that it was an anti-Bakufu strategy to legitimize the revolution. Anti-Bakufu forces considered entering into a diplomatic relationship with the West as a disgrace to the “divine nation.” They sought to “expel the barbarians,” but after battling with the West they turned to “enlightenment.” The Choshu forces fired on the joint naval forces of four nations at Shimonoseki in 1864. They attacked the Western fleet to “expel the barbarians,” but realized the tremendous disparity in military prowess; they stopped fighting and quickly switched to learning about the West’s technology. It was inevitable that they would change their objectives since defeat meant suicide under the samurai code. The Meiji Restoration, in essence, began as an effort to overcome military inferiority rather than as a deep appreciation for Western civilization.

The samurai leaders from Choshu who led the Meiji Restoration were students of the scholar Yoshida Shoin at his school Shoka Sonjuku between August 1856 and December 1858 They later became leaders of the Meiji Restoration and directed the invasion of Chosun and The Great Han Empire. Yoshida taught them the concept of “Seikanron”; the students realized their teacher’s vision when they forcibly annexed Korea.

The following narrative demonstrates that Meiji forces invaded Korea as an extension of Seikanron. First, after visiting Seoul as a special Imperial envoy to coerce Korea into signing the “Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty,” Ito Hirobumi sent a messenger to Yoshida Shoin’s grave to report on the treaty’s successful conclusion.2 The third Resident-General who also was responsible for the “annexation of Korea,” Minister of the Army Terauchi Masatake remarked: “The annexation of Korea has realized the dream that Hideyoshi failed to achieve; if they were alive, the three samurai (Kobayakawa Takakage, Kato Kiyomasa, and Konishi Yukinaga) would have been happy.”3

← 25 | 26 → Recently, Suda Tsutomu examined Yoshida Shoin’s introduction of Seikanron and how the early modern Japanese viewed Chosun. He argues that the contents of Joruri, a type of entertainment for the lower class, and Kabuki both tell stories about Japan’s military superiority over Chosun. For example, the Three Han Invasion (Sankan Seibatsu) by Empress Jingu and the Hideyoshi Invasions are popular subjects. Suda asserts that through these pastimes, the “early modern Japanese” came to view the “weak Chosun” as an object of contempt. During the Tokugawa era, Chosun was seen as such a servile country that even its king begs the Japanese army for his life. He analyzes how Yoshida Shoin’s Seikanron was introduced based on this common Japanese sentiment.4 This contempt originated with soldiers returning from the “invasion of Chosun.” Because the purpose of their heroic exploits was subjugation of a foreign country, the pleasure and excitement it evoked created a self-replicating cycle. If Yoshida Shoin’s Seikanron was based on such sentiments, the “invasion of Korea” that his students realized could not be considered “modern.”

Joruri and Kabuki often point to the Mimizuka, or “the Ear Mound,” as evidence of Toyotomi’s military superiority. It is said the Ear Mound was created to demonstrate the superiority of Toyotomi’s soldiers in front of Hokoji, which was meant to be the most impressive temple of the time to demonstrate his authority. When Tokugawa Ieyasu opened the Bakufu, however, he destroyed Hokoji, leaving only the Ear Mound to become a subject for folk entertainment. Nonetheless, the Meiji government celebrated the three-hundredth anniversary of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s death and built the Toyokuni Shrine, nationally promoting Toyotomi worship. This important evidence demonstrates that from the beginning, the Korean policy of Choshu forces leading to the “annexation of Korea” was pursuing Toyotomi’s “invasion of Korea.”

3.Crime against Humanity – Assassination of Empress Myungsung

The assassination of Empress Myungsung on October 8, 1895, is one of the most shocking events in modern Korean history. The revelation that the ← 26 | 27 → assassins were Japanese led to fierce international criticism that significantly damaged Japan’s position in the world. The new resident minister, Miura Goro, led the attack, but it is still not known why and under whose orders the assassination was carried out.

Until now, the pro-Russia policies of the Chosun royal family were the most widely accepted motive for the murder. In the 1990s, however, Choi Mun-Hyung published an analysis of this topic from the perspective of international politics. The Empress had involved Russia in order to stop Japan’s attempt to force Korea into becoming a protectorate during the Sino-Japanese War. In short, the assassination was the Japanese government’s retaliation against the Empress’s policy. Choi contends that the leader of this operation was Miura’s predecessor, Inoue Kaoru.5

The Korean-Japanese historian Kim Mun-Ja published a ground-breaking work on this event in 2009.6 He analyzed previously unexamined Japanese military documents and discovered that the vice-chief of the Imperial General Headquarters (Daihon’ei) Yamagata Aritomo and others supervised the assassination. The Imperial General Headquarters was an organization formed during wartime for the Emperor, in which the chief-of-staff was Emperor Hirohito and Major General Kawakami held the highest post as vice-chief. The background of the operation revealed by this study follows below.

The Japanese military under the first Ito Hirobumi cabinet imposed a second conscription of soldiers to increase the army to 300,000 men. It was a strategy to combat Qing China, which was said to maintain one million troops. Over the next seven years, the Japanese government concentrated on building up the military, allocating sixty to seventy percent of the national budget to military expenditure. This escalation led to the start of the Sino-Japanese War in July 1894. At this time, the military leadership, including the Imperial General Headquarters, seized the telegraph lines in the Korean peninsula that dated to the 1880s7 and acquired superiority in communications. When the Tonghak Peasant Revolution began, Qing China demanded Chosun to request troops, providing Japan with an opportunity for ← 27 | 28 → “simultaneous dispatch.”8 Japan’s Oshima brigade entered Seoul with 8,000 soldiers through Inchon.

On July 23 at 12:30 AM, the Japanese Army sent one battalion of troops to Kyongbok Palace, confined the Emperor to the palace, and occupied the Bureau of Transportation and Communications. The Japanese Army headed south right away, starting the war by attacking the Qing army at Sunghwan and Pungdo on July 25. With control over the communications system, the Japanese won the war in seven months.

A bigger problem, however, arose after the war. At the Shimonoseki Treaty signed on April 17, 1895, Japan was to receive reparations of 300 million yen as well as the Liaodong peninsula and Taiwan. However, the Triple Intervention forced the return of the Liaodong peninsula within six days. Japan had no choice but to concede, because they still had not renegotiated their unequal treaties vis-à-vis the Western powers. The Liaodong peninsula was a crucial bridge to Manchuria as well as a blockade against Qing influence over the Korean peninsula. The return of this land was not only a lost opportunity, but also a failure to achieve the war’s main objective: influence over the Korean peninsula. Given the enormous war effort, the military adamantly refused to concede.

On May 12, Yamagata Aritomo, who held the highest position within the Choshu military faction, sent a message to the Foreign Minister concerning his plan to station a battalion of troops to defend telegraph lines in Chosun, as well as to protect Japanese residents. The military’s suggestion gained momentum when the Privy Council decided to “abandon” the Liaodong peninsula on May 26. The ruler of Chosun replied that he could not allow this to happen. Ambassador Inoue, who was temporarily back in Japan, proposed providing Chosun with three million yen. He suggested that Japan needed to pay to use telegraph lines in Chosun because Chosun owned them. He offered to pay 500,000 yen each to the royal family and the government, and an extra two million yen for building the Kyungin Railroad. His strategy was to use the railroads to maintain influence over Chosun.

On the other hand, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs attempted to use diplomatic means to resolve the Army’s suggestion. They submitted a request for resident troops in the name of Kim Yun-sik, Chosun’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, so that Japan’s approval would justify stationing the Japanese army. However, the sovereign of Chosun notified the Japanese embassy in a timely fashion of the need for the complete withdrawal of 6,000 Japanese troops as soon as possible. Chosun also refused Inoue’s proposal for compensation. On July 11, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs replaced ← 28 | 29 → Inoue with Miura Goro who was previously a lieutenant general, indicating the Emperor’s decision to yield to the will of the military. Then Kawakami, the vice-chief of the Imperial General Headquarters, ordered him to assassinate the Empress. This scheme meant to threaten Chosun’s Emperor and force him to surrender in fear. The strategy was to involve Taewongun so that he would take the blame for the Empress’s assassination, then to form a pro-Japanese regime under a state of emergency. Originally, scheduled to be over by 4:00 AM in order to hide the Japanese initiative; however, Taewongun’s involvement delayed the operation so it ended between 5:30 and 6:00 AM.

Kim Mun-Ja’s work clearly proves the military’s leadership role in the event by revealing the list of names that participated in the operation, including the fifty men (“hired muscle”) and the eight officers who commanded the Japanese garrison under Vice-chief Kawakami and Resident Minister Miura.9 Second Lieutenant Miyamoto Taketaro delivered the final blow that fatally wounded the Empress.10 After the incident, Imperial General Headquarters court-martialed the eight officers in Hiroshima, but concealed the fact with silence.

The ensuing reports by journalists and diplomats – who were essentially accomplices to the incident – about “the first blow” to the Empress were revealed later as attempts to mask the real culprit. Following the Empress’s death, the most important task was to conceal that Imperial General Headquarters was behind the murder. The murder of the Korean Empress by the Japanese military to coerce Kojong for invasion of Korea is a historical scandal. Among the Choshu faction, the drive to realize Seikanron is the only basis for this crime against humanity. Although Kawakami Soroku (1848–1899) was from Satsuma, he was assimilated into the Choshu military ← 29 | 30 → faction when the army was established during the early days of the Meiji Restoration.11

4.Illegal Seizure of National Sovereignty

A.Normal Treaties during the Early Involvement with the Korean Peninsula

There was an enormous difference between Japanese attitudes toward Korea before and after the Sino-Japanese War. Beforehand, they tried to prepare all the necessary legal requirements, abiding by international law with the objective of reducing Qing influence in Chosun and establishing a firm legal basis for their new relations with Chosun.12

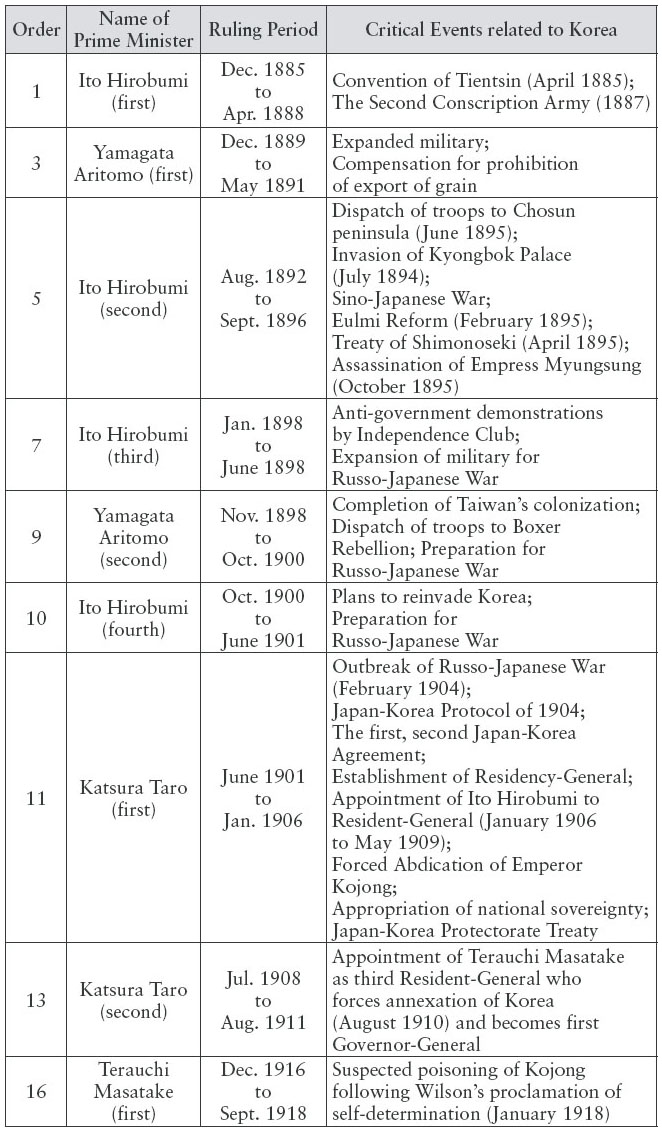

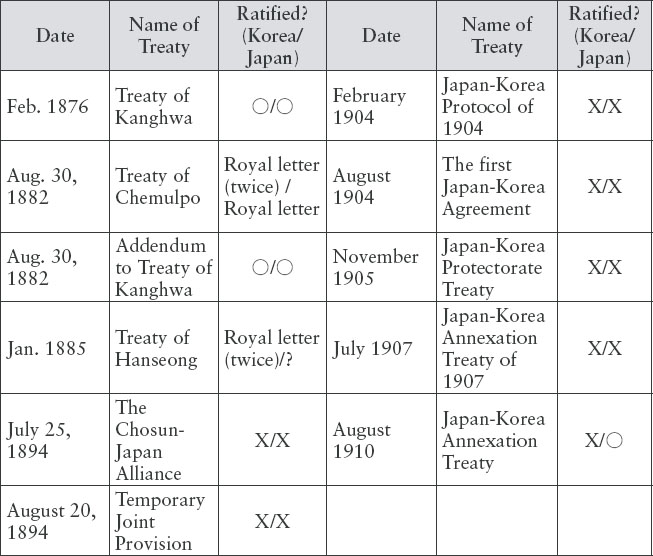

As shown in Table 1, Japan signed four important treaties with Chosun before the Sino-Japanese War. The Treaty of Kanghwa established the ← 30 | 31 → first diplomatic relations between the two nations; it contained all the requirements for both parties on carte blanche and ratification. The Treaty of Chemulpo on July 17, 1882 required Chosun’s compensation for the death of Japanese officers and the burning of the Japanese embassy during the Imo Military Rebellion. Japan demanded, not only ratification of the document, but also a message of apology from the Emperor of Chosun.13 Since Chosun was unable to deny the casualties Japan suffered during the incident, they had to yield to this demand.14 The official documents dated “the eighth month of the year of Imo” (the received date was October 20, 1882, by Bureau of Records) and sent to Japan reveal that Minister of Rites Yi Hoe-jeong expressed regret to the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs for not preventing Japanese casualties.15 Japan considered this document as the sovereign’s message equivalent to a letter of apology, sending the imperial response (which was described as “internal letter” in Chosun) through Resident Minister Hanabusa Yoshitomo. The Chosun government then sent the Emperor’s message that suggested friendly cooperation through normalization between the two countries on August 7 (lunar calendar), through Envoy Cho Byung-ho and Officer Yi Cho-yeon. The exchange of these letters between the two sovereigns provides certifying documentation beyond the ratification documents.

Table 1: Important Events during Terms of Office for the Prime Ministers in the Meiji Government belonging to the Choshu Faction

← 32 | 33 → The Japanese government attached an addendum to the Treaty of Kanghwa and the Treaty of Chemulpo and processed them together. The contents of the addendum include items such as extending the sphere of open ports (Wonsan, Pusan, and Inchon) from fifty nautical-miles to one hundred nautical-miles and permitting domestic travel by diplomats; this sub-treaty was ratified by a separate process.

Table 2: Modern Treaties Korea and Japan and Their Ratification Status

The Treaty of Hanseong signed on January of 1885 concerned a fire at the Japanese Embassy and injuries during the Kapsin Coup. This time, Chosun cornered Ambassador Takezoe Shin’ichiro by strongly arguing that Japanese and not Koreans burned the Embassy and ran away.16 Japan dispatched Minister of Foreign Affairs Inoue Kaoru as ambassador plenipotentiary to contest this position. Inoue made concerted efforts to insist on expressing regret through a royal letter, while minimizing the compensation.

← 33 | 34 → The Chosun government’s response was as follows.17 It acknowledged that the burning of the Embassy and attendant injuries occurred unexpectedly and would send a royal letter to recognize Japan’s decision to dispatch an ambassador plenipotentiary (henceforth “Royal Letter No. 1”). The Emperor avoided personal involvement by appointing the Chosun minister plenipotentiary indirectly by a royal command to the Prime Minister. After negotiations were concluded, Chosun sent another royal letter along with a delegation composed of Deputy Minister of Rites and Deputy Minister of Defense, which conveyed a “sentiment of forbearance” (henceforth “Royal Letter No. 2”). Both of these royal letters were manuscripts without the Emperor’s royal seal. The only Chosun document related to the Treaty of Hanseong with a seal (The Seal of Foreign Office) is the letter of inquiry sent by the Head of Chosun’s Foreign Office Kim Yun-shik to Japanese Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru. This letter of inquiry states the fact that the Deputy Minister of Rites and the Deputy Minister of Defense are appointed to deliver the Royal Letter No. 2. Royal command and Royal Letter No. 1 were sent together, perhaps in order to show how the letter was written, but these were did not have a seal. The condition of these documents shows Chosun’s attempt to minimize the level of apology that Japan demanded.

The Treaty of Hanseong also clearly expresses the two sovereigns’ views on the contents of the treaty. Ambassador Plenipotentiary Inoue Kaoru firmly refused to negotiate when the Chosun Minister Plenipotentiary forgot to bring the General Power of Attorney (issued by the Prime Minister on royal command) to the negotiation table on January 17, 1885. However, it has not been identified whether the Japanese Emperor issued the corresponding ratification when a Chosun delegate went to Tokyo to deliver Royal Letter No. 2. Considering that Chosun and Japan both emphasized that this treaty was initiated by Japan’s demand to negotiate through the ambassador plenipotentiary, the Japanese Emperor’s acceptance of Royal Letter No. 2 can be considered his form of ratification. In fact, the Japanese Emperor never again raised the subject of the Treaty of Hanseong.

B.Japan’s Change of Attitude after the Sino-Japanese War: Introduction of an Informal Agreement that Excludes the Emperor of Korea

As examined above, the format of the treaties signed between Chosun and Japan had no deficiencies. However, the situation changed in July 1894, when Japan started the Sino-Japanese War.

Details

- Pages

- 352

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631660522

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653054729

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653971316

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653971323

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-05472-9

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (April)

- Keywords

- Ostasien Imperialismus Kolonialismus bilaterale Beziehungen

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2015. 352 pp., 7 coloured fig., 4 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG