Clerical Exile in Late Antiquity

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Approaches to Clerical Exile in Late Antiquity: Strategies, Experiences, Memories and Social Networks

- Part I: Clerical Exile and Social Control

- Constantine and Episcopal Banishment: Continuity and Change in the Settlement of Christian Disputes

- Mapping Clerical Exile in the Vandal Kingdom (435–484)

- Enforced Career Changes, Clerical Ordination and Exile in Late Antiquity

- Part II: Clerics in Exile

- Dionysius of Alexandria in Exile: Evidence from His Letter to Germanus (Eus., h.e. 7.11)

- Exile, Identity and Space: Cyprian of Carthage and the Rhetoric of Social Formation

- Exile and the Dissemination of Donatist Congregations

- From Hippolytus to Fulgentius: Sardinia as a Place of Exile in the First Six Centuries

- Banished Bishops Were Not Alone: The Two Cases of Theodoros Anagnostes, Guardian and Assistant

- Part III: Discourses, Legacies and Memories of Clerical Exile

- Tracing the Imaginary in Imperial Rome

- Amputation Metaphors and the Rhetoric of Exile: Purity and Pollution in Late Antique Christianity

- Receptions of Exile: Athanasius of Alexandria’s Legacy

- “I Will Never Willingly Desert You”: Exile and Memory in Ambrose of Milan

- List of Contributors

The present volume results from the international research project “The Migration of Faith: Clerical Exile in Late Antiquity (325–c.600)”. The project is a collaboration between the Department of History at the University of Sheffield, the Seminar für Kirchengeschichte at the University of Halle, and the Department of Culture and Society at Aarhus University, with the Abteilung Byzanzforschung at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the HRI Digital at the Humanities Research Institute and the German Historical Institute in London as further project partners. It is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from 2014 to 2017. Ten chapters of this volume are revised versions of papers delivered at the XVII International Conference on Patristic Studies held in Oxford from 10 to 14 August 2015. For the publication of this volume we commissioned three further chapters (the two chapters by David M. Reis and Éric Fournier’s chapter on amputation metaphors). We have been very fortunate to work with such inspiring and diligent contributors and are pleased to present our findings to a wider audience so swiftly. In addition, a number of colleagues have supported the volume’s development and we would like to take this occasion to express our warmest gratitude to all of them.

At the University of Sheffield, we would like to thank John Drinkwater, Katie Hemer, Joseph Lewis, Simon Loseby, Máirín MacCarron, Harry Mawdsley, Dirk Rohmann, Giulia Vollono and Meredith Warren for reading, responding to and discussing draft versions of several chapters in this volume in the “Late Antique Reading Group”. Their feedback has been invaluable. Special thanks go to Harry Mawdsley and Jan Rausch for English proofreading, and to James Pearson for technical help.

An der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg danken wir herzlich den Hilfskräften am Lehrstuhl für Ältere Kirchengeschichte für ihre zuverlässige Arbeit. Beate Gienke, Franziska Grave, Juliane Müller und Malina Teepe haben sich mit großem Engagement der Aufgabe angenommen, den Fußnotenapparat und die Texte nach den Richtlinien für die Reihe ECCA zu bearbeiten. Ferner danken wir den Mitherausgebern von ECCA, Anders-Christian Jacobsen (Aarhus) und Christine Shepardson (Knoxville), für die Zustimmung zur Aufnahme des Bandes in die Reihe. Hermann Ühlein (Essen) vom Verlag Peter Lang danken wir für die freundliche und geduldige Betreuung bei der Entstehung des Buches.

Aarhus Universitets Forskningsfond takkes for støtte til bogens udgivelse. Tak også til Nicholas Marshall og andre medlemmer af Center for Studiet af ← 7 | 8 → Antikken og Kristendommen. Fra Datahistorisk Forening takkes Finn Verner Nielsen og Knud Viuf for at gøre en elektronisk database udarbejdet i 1989 af Merete Harding tilgængelig.

Sheffield / Halle / Aarhus, in June 2016

Julia Hillner / Jörg Ulrich / Jakob Engberg

Approaches to Clerical Exile in Late Antiquity:Strategies, Experiences, Memories and Social Networks1

Abstract: This chapter serves as both an introduction to the present volume and as an introduction to the underlying research project “The Migration of Faith: Clerical Exile in Late Antiquity (325–ca. 600)”. It lays out the overall aim of the volume to examine the immediate and long-term impact the exile of leading Christian clerics had on late antique communities. It further explores the benefits and challenges of social network analysis to enhance our understanding of this impact, a particular method championed by the “Migration of Faith” project.

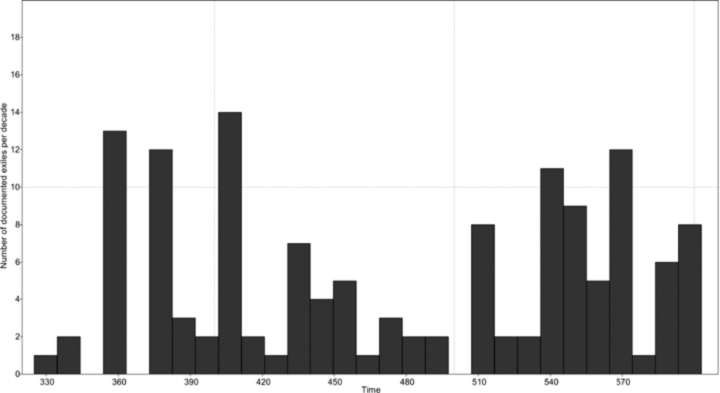

Between the time of the council of Nicaea in 325 and the end of the reign of emperor Justin II in 578, around half a thousand Christian clerics or ascetics were forced to leave the location of their office under a process that historians usually call “exile”.2 These figures, relating to the late Roman empire, rise even further when we take into account evidence covering the post-Roman kingdoms from the mid-fifth century on.3 Often, although by no means exclusively, such forced movement was a result of civic authorities’ interference with theological controversy. It is hence not surprising, as Figure 1 shows, that incidents of clerical exile seem to have multiplied around the time of intense theological debates under imperial patronage or instigation, for example under Constantius II (337–361), Theodosius I (379–395), Honorius (395–423), ← 11 | 12 → Theodosius II (408–450), Justinian I (527–565) and Justin II (565–578). Many of the iconic Christian leaders of the time famously suffered one or more periods of exile, including Athanasius of Alexandria, Meletius of Antioch, John Chrysostom, Nestorius of Constantinople, Fulgentius of Ruspe or Severus of Antioch. Over the course of this period, exiled clerics’ journeys involved over four-hundred physical places as locations of departure, arrival, or return, ranging from the Isles of Scilly in the North-western corner of Europe to Pityus on the eastern shore of the Black Sea to the “Great Oasis” (Oasis Magna, today’s El-Kharga) in the south of Roman Egypt. Clerical exile hence connected the centre and periphery of the Roman empire and its Western successor states in a way that seems to defy the progressive political fragmentation of the ancient Mediterranean in this period.4 What is more, according to our current state of research, around one thousand individuals, both male and female, can be identified as having been affected by this phenomenon: as judges, escorts, guards, friends, companions, messengers, correspondents, as visitors, servants, family members, hosts, members of congregations (old and new), as rivals, theological opponents, promoters of cult and translators of relics, or successors in post. Since such more marginal people are not usually the object of interest of late antique authors reporting on exile, our sources only allow us to name and count some of them. Therefore, recorded numbers certainly only present the tip of the iceberg. ← 12 | 13 →

Figure 1: Chronological Distribution of Recorded Cases of Exile between 325 and 6005

By all accounts, then, the forced movement of late antique clerics was an enormous social and geographical phenomenon that encompassed both the late Roman and the post-Roman world, even considering the spread of these figures over a period of nearly three-hundred years. Even more clearly, it was also a casus scribendi: the amount of legal, documentary, epistolary, polemical, pastoral, narrative and even epigraphical evidence for late antique clerical exile is truly impressive for a period that, compared with other periods of history, is seriously under-documented. In fact, late antique clerical exile was such a text-productive phenomenon that it would be hard for any historiography on the late antique Church not to engage with it in some fashion.

Given the wealth of material, it is surprising that the first monograph study of late antique exile, Daniel Washburn’s Banishment in the Later Roman Empire, 284–476, only appeared in 2012.6 This study took a comprehensive approach, investigating both lay and clerical exile. Washburn has done scholarship an excellent service by highlighting a particular late antique purpose of exile that responded to emerging Christian concepts of “crime” and “punishment”: contrary to other penal measures, exile had both the ← 13 | 14 → potential of “social hygiene”, removing the contagious offender from the community, and of “improvement”, opening the possibility of return upon change of behaviour.7 Yet, historians still have to define what was specific about “clerical” exile – and different from “lay” exile – during late antiquity: for example, its exact legal nature and relationship to ecclesiastical penalties such as deposition and excommunication, in the face of both collaboration and competition between civic and ecclesiastical authorities regarding the administration of justice over clerics in late antiquity;8 the relationships between different kinds of clerical exile: those initiated by Church Councils, those initiated by emperors, and those that can be better described as “flight” to avoid arrest; the corresponding legal and perhaps penitential procedures involved, including those leading to recall; authorities’ motivations behind choosing exile over other penalties for clerics, also given that there were immense changes to political authority in the late Roman west in particular; the corresponding purposes of clerical exile, particularly where clerics were not apparently exiled in the context of religious controversy as seems to have happened especially in some post-Roman kingdoms;9 the practicalities and the possibilities to enforce exile of clerics, and how these relate to the nature of political authority on the one hand, and the choice of location such as islands or monasteries on the other; the experiences of exiled clerics, such as the absence or presence of material maintenance; the effects on and influence of the communities and individuals exiled clerics left behind, took with them, met or were in contact with, in short, their socio-spatial networks; the opportunities and challenges clerical exile presented for cultural encounter, conversion and exchange of ideas and concepts, given that Christian identity was by no means fully formed in this period; and, most importantly, clerical exile’s corresponding legacies on the shaping of Christian identity, leadership, as well as late antique concepts and practices of space. ← 14 | 15 →

Of course, historians and theologians have considered many aspects of late antique clerical exile before, but their efforts have often focused on illuminating either the legal nature of and motivations behind its imposition, particularly in the context of the Trinitarian controversies, or on the fate and writing of individual famous clerics in exile, not on the phenomenon as a whole and its role in the making of a Christian society in late antiquity.10 This volume ← 15 | 16 → will begin to chart this territory, by considering clerical exile not as an event and individual experience, but as a process, ranging from the imposition of exile, over experiences in exile, to the commemoration of exile, which affected many. The aim of this Introduction is to establish a rigorous methodological framework in which further advances in this field can be made.

Clerical exile in late antiquity has its own unique epistemological challenges. As is true for any historical phenomenon, knowledge about clerical exile was mediated through contemporary or later produced texts and objects, and any analytical enquiry therefore has to begin by treating it as a construct, narrated and rationalised retrospectively. In the case of clerical exile, more often than not, information about a particular incident of the phenomenon derives from literary contexts, whose interests lay in telling larger stories about the Christian past, present and future, about ecclesiastical or ascetic authority, and about related heroes and spaces, either on a universal or a local scale. As we will see in this volume, both the reinterpretation of clerical exile as renewed persecution during the late antique Church’s quest for “orthodoxy”, reminiscent of Christian persecution under pagan emperors, and the positioning of clerical exile within the emerging phenomena of late antique asceticism and of episcopal leadership loom large and cast a distinctive shadow on our sources. To answer the specific questions raised above, for example on legal nature, locations, and social effects of clerical exile, we therefore need to develop precise methodological strategies of dismantling our stories for “factual” data. Yet, while acknowledging that there are probably ← 16 | 17 → historical “truths” behind many clerical exile stories, we also need to ask ourselves to what extent such dismantling is possible or desirable in each individual case. For example, it may be difficult to recover the precise legal circumstances of Constantine’s banishment of Athanasius of Alexandria to Gaul following his deposition at the Council of Tyre in 335. According to Athanasius himself, he was exiled due to a charge of treason his opponents concocted (interference with the grain supply from Egypt to Constantinople), which allegedly alarmed the otherwise sympathetic Constantine, and certainly not on theological grounds.11 It was important for Athanasius to sever any potential link his audience could draw between his exile and his deposition decided at Tyre in order to divest the council’s doctrinal position, and his theological rivals, of imperial endorsement. Yet, historians, who have to rely solely on Athanasius’ testimony, cannot be so sure of Athanasius’ correct depiction of the legal situation.12 Nonetheless, Athanasius’ version of events is important as it gives us a glimpse into the literary afterlife of clerical exile. All stories about clerical exile aimed to provide “models” of clerical exile, and – however changing, conflicting or complementary – these models may have shaped how late antique audiences, including other exiled clerics themselves, understood and repurposed the phenomenon and its place within the development of Christianity. As has been shown for Christian martyrdom, the creation of the martyr did not happen in the actual event of their death (fictitious in some case anyway), but in the act of commemoration. The martyr was important as “an idea or set of values that a community held dear”.13 The same, this volume shows, may over time have become true for the exiled cleric, even though this development was not without controversy.

1. Strategies, Experiences, Memories

The chapters of this volume are, with three exceptions, revised versions of papers presented at the XVII International Conference on Patristics Studies in August 2015, in a workshop convened by the Sheffield-based, AHRC-sponsored international research project “The Migration of Faith: Clerical Exile in Late Antiquity, 325–600” (2014–2017), led by Jakob Engberg, Jörg Ulrich and myself. The workshop brought together colleagues working in a range of disciplines (theologians, medieval historians, ancient historians and classicists) and from a number of national academic cultures (Austria, Britain, ← 17 | 18 → Canada, Denmark, Germany, Spain, United States). Unlike the sponsoring research project, which starts with the Council of Nicaea and to which I will return further below, the workshop also considered third-century evidence on clerical exile. Since one of the purposes of this volume is to discuss exile as a literary paradigm, extending the chronological parametres is crucially important. Christian clerics had of course been exiled by Roman authorities long before 325, during the foundational period of early Christian persecutions, with potential repercussions on how later Christians thought and wrote about exile in a post-persecution context. In addition, this long view allows better to measure the astonishing rise of exile as a penalty for clerics from Constantine on, and as a significant topic of Christian writing. The latest incidents of clerical exile examined in this volume date to the early sixth century, when exile had long become the established penalty for troublesome clerics, a development that arguably started to influence how lay offenders were treated from this period on.

Within these nearly three-hundred years of history, the volume explores a wide range of evidence from around the Mediterranean, including Vandal North Africa. The chapters are arranged in a way that roughly follows a late antique clerical exile’s “journey”, within a framework that is both conceptual and chronological. The first group of chapters (Fournier, Mawdsley, Rohmann) approaches clerical exile from the perspective of those imposing it. They highlight the measure’s flexibility that made it attractive to a variety of political, theological and penal strategies, but also its ability to respond to a core requirement of Christian punishment, initially for clerics, but increasingly also for lay people, and felt by late Roman and post-Roman political leaders alike: the avoidance of the death penalty. The next group of chapters (Reis, Ulrich, Heil, Engberg, Vallejo Girvés) shifts the focus away from a top-down scenario of social control and conflict management to the historical contexts in which exiled clerics lived through their fate. They include the examination of influential Christian authorities in exile, such as Cyprian of Carthage, Dionysius of Alexandria and Fulgentius of Ruspe, over, perhaps deliberately so, much less well known clerics in exiles, such as “Donatist” leaders, to the activities and functions of exiles’ companions, both men and women. The final chapters (Reis, Fournier, Barry, Natal) direct their gaze onto the discursive rationalisation of exile, of those who pronounced exile, those who were subject to it, and those who were never exiled themselves. In their hands, stories of exile were transformed into symbolic currency, able to promote or undermine civic and ecclesiastical authority.

The volume opens, appropriately, with Éric Fournier’s view on Constantine’s adoption of exile as a strategy to settle inner-Christian conflict, the first Roman emperor to do so. Constantine’s wavering attitude towards ← 18 | 19 → inner-Christian conflict is sometimes considered inconsistent,14 but Fournier argues that we need to see Constantine as more of a “hands-off” and hence traditional emperor in religious affairs than sometimes thought. His main interest was not in coercing individual belief, but in “collective profession of unity”. He respected the ancient tradition of conciliar decision-making of the Christian Church, and followed up decisions on deposition and excommunication with exile when asked to do so, choosing another tradition, a penalty reserved for the elites, in order to safeguard the prestige of clerical office. Of course, there were some procedural innovations under Constantine, such as the convening of “appeal” councils during the “Donatist” controversy, and these set a precedent, tying Church and Empire closely together. Overall, however, Fournier reminds us of the continuities, rather than the novelties, in Constantine’s adoption of clerical exile.

Inconsistencies also play a role in Harry Mawdsley’s study of Vandal kings’ embracing of exile as a measure to deal with recalcitrant clergy. Employing pioneering quantitative and digital analysis of geographical trends regarding locations both of exiled clerics’ home communities and of exile under Geiseric and Huneric, Mawdsley shows that the two kings pursued very different penal strategies when imposing clerical exile. While Geiseric was interested in economic survival in the Vandal core territory of Zeugitana, and did not distinguish between lay and clerical exile, Huneric’s aim was to enforce religious conformity across Vandal North Africa by targeting Nicene Church leaders. Paradoxically, Huneric’s concepts of social control mirrored contemporary developments in the Roman empire, which by the fifth century had adopted a more authoritarian supervision of clerical dissidents than Constantine ever had.

Dirk Rohmann’s chapter returns us to the fifth- and sixth-century Roman empire, and continues to explore the relationship between lay and clerical exile. Rohmann demonstrates that the social and legal status of Christian clerics (among others evidenced by their exemption from the death penalty), in combination with the emergent practice of Christian asylum, brought about a new form of exile also for lay individuals: forced clerical ordination, often in a remote provincial city. This development arguably responded to the increased requirement for Christian emperors to show themselves merciful, while at the same time solving the problems that came with keeping political rivals – the “criminals” for whom forced ordination is mostly attested – alive. Yet, it should be noted that, while contemporary sources may present forced ordinations as an imperial strategy, and over time the practice may have revolutionised the concept of “lay exile”, we should understand it more as an experiment, not the least because it was less a penalty than a by no means ← 19 | 20 → automatic outcome of negotiations between the “criminal”, Christian institutions and imperial authorities.

With its emphasis on both penal strategies and individuals’ attempts to escape and subvert such strategies, Rohmann’s contribution links the part of the volume that focusses on social control to the part dealing with specific exiled persons and groups. Again this part starts with the discussion of trail-blazing historical figures, Cyprian of Carthage and Dionysius of Alexandria, both in exile during the mid-third century Christian persecutions. David M. Reis concentrates on Cyprian of Carthage’s first exile during the persecution of Decius, which, not unlike the cases investigated by Rohmann, was not an outcome of a judicial sentence, but of flight, but without the protection provided by the later institution of Christian asylum. Reis shows how Cyprian struggled to justify his behaviour against the example of those who had faced violent persecution and death, the confessors and martyrs. His chapter argues that in the process Cyprian redefined the category of the confessor-martyr, by adding the voluntary taking on of suffering through flight to the legitimate responses to persecution. In a similar vein, Jörg Ulrich’s discussion of the exile of Dionysius of Alexandria during the persecution of Valerian shows that third-century bishops did not only labour to defend voluntary flight, but even legal exile. Through carefully sorting out the narrative levels in a letter Dionysius wrote to a possible confessor, preserved in Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History, Ulrich shows how Dionysius attempted to shape the memory of his exile against accusations about this comfortable experience, by presenting the latter as part of a divine plan that allowed him to continue his work for the Christian community as a bishop through liturgical activity, miracles and staying close to the urban centre. Both Cyprian and Dionysius of course presented a lens through which late antique clerics, after Constantine, could interpret their exiles, at a time when a fatal end through persecution was not an option anymore. There was hence not only legal continuity of exile as an elite penalty from the third century, as Fournier argues, but also the groundwork of a new martyrology of exile was laid in this period.

In the next chapter, Uta Heil revisits Vandal North Africa, this time from the perspective of another epochal clerical exile, Fulgentius of Ruspe. Like Reis and Ulrich focussing on an exiled cleric’s own writing, Heil charts the chronology of Fulgentius’ works and aligns it with his ca. fifteen-year-long exile under Thrasamund. This allows Heil to show that Fulgentius’ prominence and his social network, particularly in the East, grew substantially during his time in exile and that his exile had a profound effect on his theological thought. As Heil puts it, Fulgentius’ exile was like a “think tank”. Fulgentius became a sought-after expert on theological questions, even by Thrasamund himself, who interrupted the bishop’s exile to seek his advice on the Christological quarrels in the Eastern Church. The chronological gap between Reis’s and ← 20 | 21 → Ulrich’s chapters on the one hand and Heil’s chapter on the other allows us to appreciate the immense “normalisation” of clerical exile over the intervening two-hundred and fifty years. As Heil also shows, Fulgentius’ entire clerical training had been shaped by witnessing exile under Huneric, at a time when, as Harry Mawdsley describes in the volume, hundreds of clerics had been forcibly moved. In early sixth-century North Africa, exile, then, had almost become part of an episcopal career.

Jakob Engberg continues to investigate the mechanisms of network-building in and through clerical exile, again in North Africa. His focus is not on individual exiles, however, but on the effect of exile on an entire religious group, so-called “Donatists”, over the fourth and into the early fifth century. Engberg shows that the disparity between the frequency of normative legal and “Catholic” sources demanding exile for “Donatist” clerics, and sources that name or describe concrete incidents of “Donatist” exile, in Africa or elsewhere, is truly striking. Rather than leading us to conclude that “Donatist” exile did in fact not happen, Engberg argues that a number of factors could play a role in our difficulties to reconstruct it, both external (the low survival rate of Donatist literature) and, more importantly, intrinsic to Donatism: In contrast to many other late antique Christian writers, Donatist writers may in fact not have seen exile as a cornerstone of “Donatist” identity, for practical, “ethnic” or theological reasons. As such, even where it does not allow us to trace dissemination of Donatism itself, the “silence” of Donatist sources throws the ubiquity of references to exile in “Catholic” texts into sharp relief, but also questions its purpose.

Details

- Pages

- 283

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631665978

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631694275

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631694282

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653060515

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-06051-5

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (September)

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2016. 283 pp., 4 b/w ill., 5 coloured ill., 4 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG