How to Become Jewish Americans?

The «A Bintel Brief» Advice Column in Abraham Cahan’s Yiddish «Forverts»

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table Of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Jewish Immigration from Eastern Europe

- 2.1 Russian Jewish Emigration to the United States

- 2.2 Reasons for Emigration

- 2.3 Demographic Characteristics

- 2.4 The Cultural Baggage of Immigrants

- 3. The Forverts – Origins and Ideology

- 3.1 Creating a New Form of a Yiddish Press

- 3.2 The Origins of A Bintel Brief

- 4. A Bintel Brief: Characteristics and Content

- 4.1 Main Characteristics of the Column

- 4.2 The Structure of A Bintel Brief

- 4.3 The Role of the Editor and His Answers: Guidance and Authority

- 5. The Situation of Russian Jewish Immigrants in America

- 5.1 Separating the Desirables from the Undesirables: The Dillingham Commission

- 5.2 Coping with Prejudices against Jewish Immigrants

- 5.3 Abraham Cahan’s View on Acculturation: Necessary Steps towards Successful Integration

- 5.4 Facing a New Life – A Bintel Brief as First Aid to Jewish Immigrants

- 5.5 Conclusion

- 6. The Language of A Bintel Brief

- 6.1 Yiddish in the United States

- 6.2 Attitudes towards English among Eastern European Jewish Immigrants

- 6.3 Languages in Contact – The Americanization of Yiddish

- 6.4 Writing about Language: The Use of Yiddish and English as a Topic in A Bintel Brief

- 6.5 Conclusion

- 7. Changing Roles and Values in Jewish Family Life

- 7.1 The Emigration of Jewish Families: The Impact of Family Life

- 7.2 Patterns of Jewish Family Life

- 7.3 Jewish Families in A Bintel Brief: Challenges of Changed Social Structures

- 7.4 Conclusion

- 8. Between Heartaches and the Missing Matchmaker: Love and Marriage

- 8.1 Love and Marriage in the Jewish Shtetl

- 8.2 Love as a Central Theme in Abraham Cahan’s Writing

- 8.3 Courting and Gender Relations in Urban American Life

- 8.4 Caught Between Infatuation and Commitment: The Growing Importance of Love

- 8.5 In Search of Guidance: The Choice of a Suitable Spouse

- 8.6 Intermarriage: A Controversial Issue and Its Possible Consequences

- 8.7 Love Stories and the Life Novel

- 8.8 Conclusion

- 9. Socialism and Unionism: Jewish Work Life in the United States

- 9.1 Jewish Socialist Aspirations Prior to Emigration

- 9.2 Equal, Yet Different: The Jewish National Question

- 9.3 Jewish Radicalism in the United States

- 9.4 Abraham Cahan’s Involvement in the Radical Movement

- 9.5 Socialist Ideas in A Bintel Brief: Torn between Loyalty and Opportunity

- 9.6 Labor Unions as a Form of Immediate Help

- 9.7 Conclusion

- 10. Creating a New Jewish Identity: Jewish Faith or Culture?

- 10.1 Religious Re-Orientation within the Russian Jewish Community

- 10.2 Judaism in America

- 10.3 Integrating Judaism into American Life

- 10.4 Combining Socialism and Jewish Identity

- 10.5 Ethnic and Religious Identification

- 10.6 Conversion as the Ultimate Betrayal

- 10.7 Jewish Relations with Gentiles

- 10.8 Conclusion

- 11. Conclusions

- Appendix: Contents of Letters

- Bibliography

Verther redaktor fun “forverts”! Ikh bevunder dem shtarken tsutroyen un gloyben, vos ayere lezer hoben in dem “bintel brief.” Mir kumt for, az bay aykh zitst der hekhster rikhter fun land un mishpt ale sorten pasirungen fun leben mit seykhl, mit yoysher un mit treyst vort.1

In the quote above, taken from the popular A Bintel Brief column in the Yiddish New York newspaper Forverts, a young man expresses his admiration and respect for the editor. After its first publication on January 20th, 1906, the A Bintel Brief column ran as the most enduring feature of the Forverts2 for over seven decades. Roughly 55,000 letters appeared in the newspaper, followed by empathetic pieces of advice from the editorship. A Bintel Brief offered the readers of the Forverts the opportunity to write about whatever problems bothered them in their lives. Then selected letters were printed together with the editor’s advice. The problems the writers described in their letters were far more than cries for help or justice. In the column, the editor offered a variety of stories, ranging from tragic autobiographical accounts to amusing short anecdotes from Jewish immigrant life. What they all had in common was their richness in detail which made those stories such a success. Ninety years after the first published letter and twenty-seven since the last, Jeffrey Shandler in his article for the English version of the Forverts, The Jewish Daily Forward, recalls how to many readers A Bintel Brief embodied “the ← 9 | 10 → essence of the Eastern European Jewish immigrant experience” what “remains a compelling artifact of Yiddish-speaking Jewry’s dynamic American experience.”3

The following study taps this rich source of information about the lives of Eastern European Jews in the United States. As the first finished and accessible extensive study of the A Bintel Brief column, it encompasses more than a decade worth of letters, starting with the first letter in 1906, offering the reader an outline of the general structure and contents of A Bintel Brief, before zooming in from the general overview to a specific concern of the Jewish community on the Lower East Side – their first encounters with American mainstream culture. In a detailed analysis of the column, the study focuses on the efforts of the Jewish readership of the socialist Forverts towards their integration into American society by re-defining their Jewish identity.

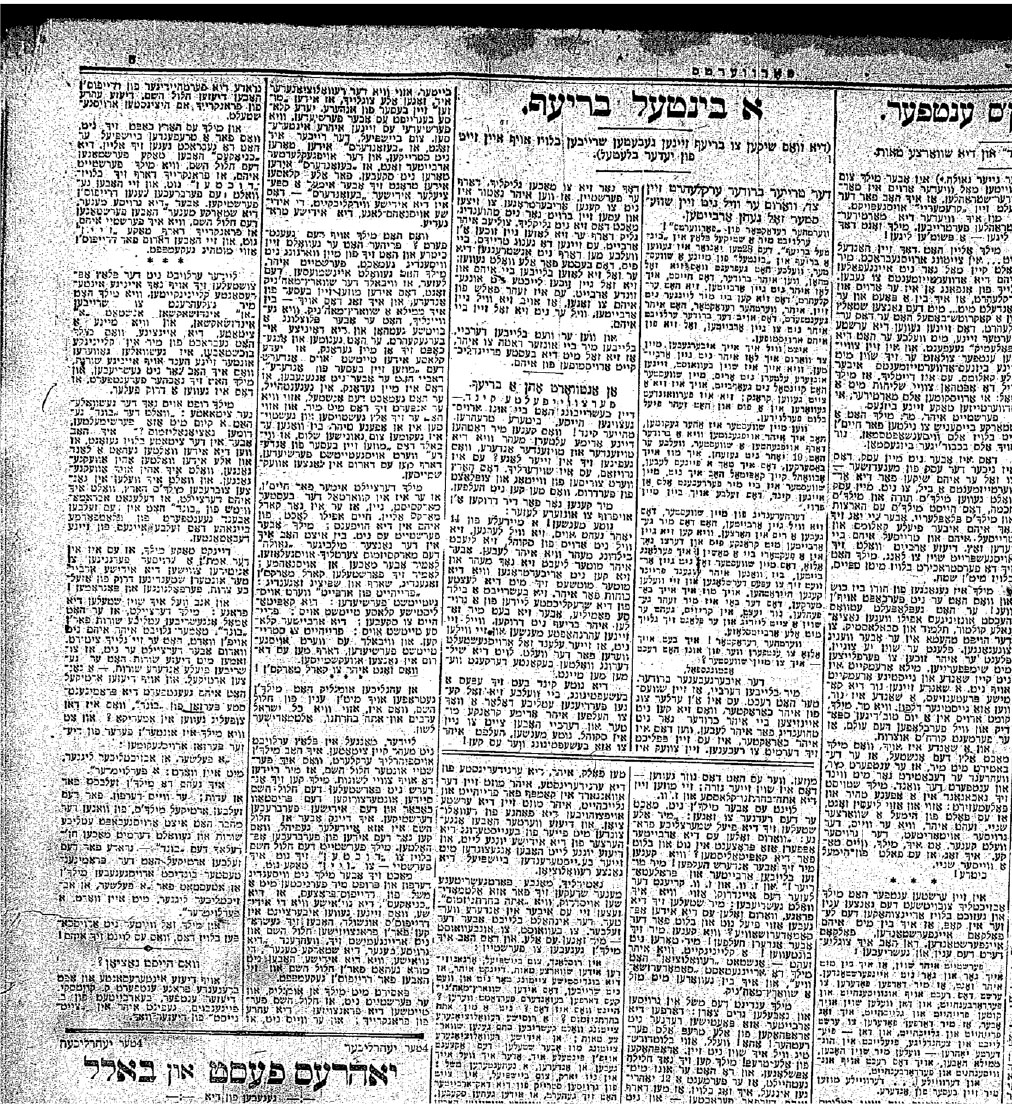

Fig. 1: “A Bintel Brief.” Forverts 7 Feb. 1908: 5, print.

The Forverts was founded during the greatest wave of emigration from Eastern Europe to the United States. Between 1880 and 1914 almost 2,000,000 Jews left the Pale of Settlement, an area in the western part of the Russian Empire designated by the Russian government for Jewish settlement.4 The Pale encompassed great parts of present-day Belarus, Lithuania, Moldova, Ukraine, parts of western Russia as well as eastern Poland, all incorporated into Imperial Russia at that point of time. Even though large Jewish communities could also be found in eastern Galicia, then part of Austria-Hungary, the majority of Yiddish-speaking Jewish communities in Eastern Europe was located in the Russian Pale of Settlement. While some families tried to find their fortune in South America, most Russian Jewish emigrants chose the United States as the country of their destination, thus creating a considerable potential readership for the Forverts. As the circulation of about 200,000 copies shortly after World War I suggests, the Forverts remained of great relevance for the opinion-building of the Yiddish speaking community in New York City and beyond for several decades.5

The rapid influx of immigrants as in the case of Russian Jews6 had great impact on the formation of the immigrant community itself as well as on their American neighbors. A clash of cultures was bound to occur on a large scale, as the Jewish immigrants and their traditions faced the gentile American way of life. In addition to the foreign American culture, the poorly educated Russian Jews experienced grinding poverty. Upon their arrival in the United States, it took some time before the miserable economic situation of those Jewish immigrants could change. Thus, Jewish immigrant life in the United States soon turned out to be both frustrating and fulfilling at the same time, as Harvey and Rima Greenberg point out in their brief psychological study of the A Bintel Brief column.7 The poverty might have been frustrating, but those immigrants could hope for a better life than in Russia because in the United States they experienced ← 11 | 12 → equal rights under the law, the right to practice their faith, a life in safety from pogroms and persecution, and the right to vote.8

In Russia, religious and political persecution of Jews was omnipresent at that time. Following the May Laws of 1882, many Jews were forbidden to resettle in the rural areas of the Pale.9 As a consequence, Jews of working age felt forced to move to cities like Odessa, Minsk or Kiev in order to try and make a living in the few permitted occupational fields available to them. There, they encountered the modern secular lifestyle of thriving industrial cities and the growing socialist and anarchist movement.

The Jews who could not make a living in the towns and cities of the Pale, chose to emigrate overseas. Within a short time, they moved from a small rural town (shtetl) into a city like New York with its urban lifestyle. As the letters to the A Bintel Brief editor reveal, many writers relocated directly from small, under-developed provincial shtetlakh with a dominating Jewish population to the metropolitan area of industrialized New York. Their old modes of life were no longer adequate and seemed partly outdated, for the lifestyle in the United States brought forward the challenges of a modern city. In addition, Jewish immigrants, just like other newcomer groups, were likely to bring problems with them that had appeared within their community in their country of origin. The main problems, however, were directly connected to American mainstream culture. First, in New York, Jewish immigrants found themselves in a largely gentile surrounding. Even though they moved into Jewish neighborhoods at first, the boundaries between gentile and Jewish quarters proved to be permeable, thus allowing immigrants to move and work outside the limitations of their Jewish homes. Second, those influenced by socialist ideas from Russia, could join the growing Jewish labor movement in the United States which promised to improve their miserable economic and social status.10 This way, socialism on the one side, and the secular lifestyle of New York on the other side, constantly challenged Jewish Orthodox religious rituals as well as century-old Jewish traditions concerning gender roles, the observance of religious laws or suitable occupations. In their letters to the editor, the writers vividly describe in detail how they try to reconcile their Yiddish identity with an American lifestyle, thus giving a deep and thorough insight into Jewish immigrant life at that point of time. ← 12 | 13 →

Previous Research on A Bintel Brief

The popular A Bintel Brief column has not gone unnoticed by historians as well as sociologists. Yet despite numerous quotes from the column, an extensive study of its contents is lacking. Instead of a detailed content analysis, the A Bintel Brief column remains a side note to Jewish life on the Lower East Side. Thus, the study at hand aims at closing this gap in information by providing a thorough analysis of the A Bintel Brief column and its contents at a decisive time of Jewish immigration to the United States.

The advice column A Bintel Brief was inextricably tied to the ideas of its co-founder and later editor-in-chief Abraham Cahan. He was the driving force behind the Forverts, directing the newspaper to great popularity and economic success in New York and beyond. An immigrant himself, Cahan experienced the United States through the lenses of a Russian Jew, immigrant and new American. He tried to combine all three parts in his life as a publisher, journalist and community leader. When leafing through anthologies on Jewish immigration history in America, the reader will notice how historians like Irving Howe or Ronald Sanders include quotes by Cahan more frequently than by other prominent Jewish immigrants. Cahan’s articles, Yiddish as well as English, parts of speeches, and comments are used to illustrate how a Jewish journalist and social critic viewed the Jewish immigrant situation in the United States. Because of his involvement in shaping the public opinion of the Russian Jewish community in the United States, Cahan can certainly be viewed as a reliable and well-established authority on the Jewish immigrant situation of his times.

Just as his journalistic achievements, Cahan’s literary work has received considerable attention by critics. Most prominently, his novel The Rise of David Levinsky (1917) and the novella Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto (1896) have been the center of attention among literary critics.11 So far most of the research on Cahan’s journalistic work has focused mainly on his English writings for the Commercial Advertiser and other English-language New York newspapers, but scholars have recognized the importance of Cahan’s Yiddish publications as well, which is indicated by the number of references to Cahan and his Yiddish journalistic contributions in various introductions to New York’s Lower East Side ← 13 | 14 → history as well as general Jewish immigration history.12 Even though many of Cahan’s Yiddish quotes are taken from his times at the Forverts (which again shows that this phase in Cahan’s life is considered to be very important), overall, more research has been conducted on Cahan’s English writings, before his time as the editor-in-chief of the Forverts.

Cahan himself supplied a considerable amount of information about his editorship at the Forverts in his autobiography of five volumes Bleter fun mayn lebn,13 of which Leon Stein translated the first and second volume into English.14 The remaining three volumes, containing Cahan’s accounts of his first years in the United States and the founding of the Forverts remain available only in Yiddish. Also, while Moses Rischin published an extensive study on Cahan’s articles for the Commercial Advertiser,15 the interested reader will search in vain for a comparable publication analyzing Cahan’s journalistic work at the Forverts. However, Isaac Metzker’s two compilations, which print a translated selection of the A Bintel Brief column and have been reprinted by several publishers, illustrate the persisting interest in Cahan’s journalistic work.16 Altogether, Metzker translated over 120 letters, ranging from the very beginning of A Bintel Brief in 1906 to 1980. As Metzker explains in his introduction to the first volume, he condensed some of the letters.17 Also, most of the editor’s answers to the letters were ← 14 | 15 → summarized. In some cases Metzker even presents only a very short synopsis covering the essence of the editor’s reply to the letter. In search of suspenseful stories, Metzker selected the letters to be printed in his book according to his own interests. In the introduction to the first volume, he explains his intentions: “In selecting the letters my purpose was to choose those which depict the true story of the immigrants, uprooted from the Old World, who came here determined to build a new life.”18 The selected letters show only a very small fraction of the letters published in those seven decades and the reader should not consider them as being representative for the entire column. Rather, they give an entertaining, yet momentous glimpse of A Bintel Brief that is meant to entertain a general readership.

Among the various sources of information about the column, four studies of A Bintel Brief deserve special attention. The first known study of A Bintel Brief was initiated by William Thomas, the founder of the Chicago School of Sociology. Thomas discovered the letters in 1918 while working on Americanization studies sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.19 He wanted to examine how Eastern European Jewish immigrants arrived at new definitions of their changed situation in the United States.20 Thomas studied the foreign language press “as a major instrument for creating a sense of community among immigrants feeling the clash of the old and the new in America from a sociological point of view.”21 With the aid of his assistants Thomas translated about one thousand letters. According to Marvin Bressler, Thomas was impressed by the “extraordinary versatility of the Bintl Brief as a research source.”22 To him “the existence and the popularity of the Bintl Brief was an attempt on the part of the community to find in the editor a secular rabbi-surrogate to perform the community function which had been traditionally reserved for religious authority.”23 Unfortunately, Thomas died in 1947 before he was able to finish his ← 15 | 16 → often interrupted study of the newspaper column. A contemporary of Thomas, George Wolfe independently translated two six-month periods of A Bintel Brief as parts of his M.A. thesis in the years 1929–1933.24 With only few remaining copies of Wolfe’s research and their poor condition, however, his findings are not readily available as a basis for further studies of A Bintel Brief.25

In his attempt to delve deeper into the contents of A Bintel Brief, the Chicago sociologist Robert Park, just like Thomas, never completed his study of A Bintel Brief. Some of his initial results, though, Park included in his writings on social control in the 1960s. There he explains how Cahan, above all, tried to create a new kind of press for the common reader.26 Up to the point of the foundation of the Forverts, Jewish newspapers and weekly magazines had been targeted at an intellectual elite, written in a language that Eastern European Jews with their rather limited education could only partly understand, and addressing issues that did not relate to problems of working class immigrants. When Cahan took over the Forverts, he wanted to establish a newspaper that would be written in a widely understood language among Jewish immigrants, namely Yiddish, and take up problems that would interest a general readership.27 A Bintel Brief can be considered the most prominent feature of the newspaper that fits his concept, because there the reader could find problems of real people coming directly from the Jewish quarters onto the pages of the Forverts.

The most recent study of the A Bintel Brief column is a B.A. thesis by Jeremy Asher Dauber of Harvard University.28 Dauber focuses on creating a theoretical framework for the analysis of advice columns, their creation, dissemination, and reception in general. In his thesis, Dauber uses A Bintel Brief solely as a case study to illustrate how his cultural theories operate. He studied the letters between 1906 and 1909 and chose the representation of love and relationships for his case ← 16 | 17 → study. During his research, Dauber was able to gain access to Wolfe’s thesis and therefore mainly refers to Wolfe’s findings and Bressler’s brief study of Jewish behavioral patterns in A Bintel Brief as secondary sources on this advice column.

Beside those four projects by Park, Wolfe, Thomas and Dauber, to the present day no extensive research has been conducted on the column, its contents or impact. Several introductions to the history of Jews in the United States have printed a few A Bintel Brief letters or quotes from letters to illustrate the Jewish immigrant situation during the first two or three decades of the 20th century. Sanders, for instance, devotes an entire chapter in The Downtown Jews to the “Bundle of Letters.” Even though the subtitle of the publication is Portraits of an Immigrant Generation, it remains a loosely constructed biography of Cahan. Like Howe in How We Lived and The World of Our Fathers (among others), Sanders outlines how Cahan came up with the idea of A Bintel Brief, but does not reveal any substantial information about the contents of the column. Interestingly, in World of Our Fathers no other name appears more often than Abraham Cahan, no newspaper more than the Forverts, and no novel more than The Rise of David Levinsky.

In addition to Metzker’s compilation, the A Bintel Brief column has received attention in a number of popular sources also targeted at a general readership with no intention of further extensive research. Naturally, the Jewish Daily Forward itself regularly publishes articles referring to its former column on its website.29 Addressing a readership that was not yet born when the column appeared, the children’s website of PBS devotes a page to the A Bintel Brief advice column in its “Big Apple History” of New York.30 Other sources with information about A Bintel Brief are Wikipedia or even a group in the popular social network Facebook. In most cases, however, those sources refer to a few selected letters from Metzker’s selection, thus limiting the interested reader’s view on A Bintel Brief. Nevertheless, they support the assumption that A Bintel Brief continues to fascinate readers over forty years after the publication of the last letter.

The popularity of the A Bintel Brief column among its Yiddish readers at a decisive point of time of Jewish immigration to the United States and the considerable attention the column has received by scholars of Jewish American history serve as a motivation to analyze how the topic of acculturation is presented in the letters and answers by the editor. The study will encompass an unprecedented ← 17 | 18 → number of letters which will allow to draw reliable conclusions about the tensions and problems concerning the acculturation process within the Forverts readership. Instead of using the column as a side-note to Jewish life on the Lower East Side, exemplified in a few excerpts taken from the column, the A Bintel Brief will be at the center of the following study. The number of letters referred to exceeds all previous attempts, as it does not need to limit itself to the selections by Metzker or Dauber, thus allowing a new perspective on A Bintel Brief.

How to Become Jewish American? – Acculturation of Eastern European Jews

The impressive circulation indicates that Abraham Cahan directed an influential mass medium ready at hand.31 Against the backdrop of the popularity of the Forverts, the issue of opinion shaping with the help of the newspaper suggests itself further research when analyzing the A Bintel Brief column. Historians like Irving Howe further confirm the importance of the Forverts as an important source of information for Jews on the Lower East Side. As a column consisting of letters from readers, the problems presented come from within the community rather than their neighbors outside the Lower East Side, thus pointing at concerns which some Jews might not have dared to share outside the protected space of a Yiddish newspaper. Consequently, the A Bintel Brief column could supply its readership with information on life in America and thus directed their interpretation of American mainstream culture.

Eastern European Jewish immigrants arrived in the United States with high hopes for economic and social improvement. At the same time, however, those individuals were shaped by the Yiddish culture of the Pale of Settlement32 where ← 18 | 19 → they had lived their lives relatively secluded from Russian culture. In the Pale, Jews had defined themselves and were defined by their gentile neighbors, and by their religion as well as culture, which were tightly intertwined. Upon their arrival in the United States, those immigrants could not take off their culture like a garment, but needed a phase of transition in order to become familiar with American customs. This balancing act between their Yiddish identity and the acceptance of American mainstream culture as a safeguard against economic and social disadvantage serves as the guiding research question in the following analysis of A Bintel Brief. It incorporates the assumption that Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe searched for a way to become Americans without entirely discarding their Yiddish identity. The following study provides a systematic approach to the question of acculturation, supported by the considerable number of more than 9,500 letters published between the first A Bintel Brief column in 1906 and 1918. In a detailed analysis of the column, the approach to acculturation as presented in the column will be assessed. Considering Cahan’s work as a novelist and journalist for American newspapers, it can be assumed that the topic of acculturation appeared in A Bintel Brief just as often as in his other publications. In his answers, the editor articulates the tensions within the Yiddish-speaking readership in order to reveal how the writers handle differences between their culture and American urban customs. The purpose of this study will be to identify how the editor presents the issues in relation to the topic of acculturation.

In her thesis on Jewish-American literature Claudia Görg explains how the self-perception of Jewish authors changed from the first to the second generation with a complete turnaround.33 Accordingly, I will determine the process of becoming a Jewish American as presented in A Bintel Brief during the time-span chosen for the analysis by identifying which parts of their Yiddish culture and religion the immigrants considered essential to their Jewish identity. In the almost exclusively Jewish shtetl, its inhabitants directed their family lives but also work and schooling according to the prescription of Orthodox Judaism as well as century old traditions. They did not have to accept a secular lifestyle in public while retreating to the private sphere of their homes to practice their religion. As a consequence, the lines between purely religious prescriptions as Judaic scriptures ← 19 | 20 → dictated them, and elements of folk culture became fluid. In the United States, however, religion was a private matter, subordinated to secular legislation as well as American mainstream culture which incorporated countless denominations.

In order to create a complete picture of the editor’s presentation of acculturation, the analysis differentiates between problem groups as to their relation to the acculturation process of Eastern European Jews. The need to acculturate in order to ensure economic and social advance was greater at the workplace, for example, than in matters of love. In my analysis I will show in which areas of their daily lives those immigrants adopted American ways and in which situations they insisted on retaining their shtetl traditions. In a next step, the motivation underlying their choices needs to be clarified. The process of becoming Jewish Americans as represented in A Bintel Brief mirrors mainly the point of view of the editor and his readers who identified themselves with his ideas. Other groups within the Eastern European Jewish community, with no interest in the socialist movement, for example, or religious community leaders, might have pursued different goals concerning their integration, disagreeing with Cahan’s worldview in some points.

More than a century after the first letters were published, it cannot be proven to a satisfactory degree how many of the letters published in the A Bintel Brief column had been originally sent in by readers. However, it needs to be kept in mind that authenticity was propagated in the A Bintel Brief column and the readership of the Forverts readily accepted the letters as original documents. As this study analyzes the topic of acculturation of Eastern European Jews in A Bintel Brief, it will examine the topic as presented in this advice column with a focus on the adjustments suggested to the readership by the editor as well as by the writers in their letters. Thus, the main objective remains to define what ideas about the future of Yiddish culture in the United States the influential Forverts propagated by its choice of letters in print.

In the effort to analyze how the Eastern European Jews expressed their encounters with American mainstream culture in A Bintel Brief, the anthropological concept of acculturation will be used as it has been applied to describe changes of cultures in contact. In the course of research on culture contact, the definition of acculturation has undergone a number of revisions, thus offering differing points of view on this subject. In the study at hand, the early definitions of acculturation will used as they represent the view on this field of research closest to the first studies on A Bintel Brief. Robert Redfield, Ralph Linton, and Melville Herskovits provided the first systematic definition of acculturation to gain scholarly attention. They set assimilation apart from acculturation, with ← 20 | 21 → assimilation being a phase of acculturation. To them, acculturation can be described as a cultural change that occurs when two cultures meet rather than the adoption of the dominant culture:

Acculturation comprehends those phenomena which result when groups of individuals having different cultures come into continuous first-hand contact, with subsequent changes in the original cultural patterns of either or both groups… under this definition acculturation is to be distinguished from … assimilation, which is at times a phase of acculturation.34

According to this definition, the term acculturation does not define the degree of acceptance of a foreign culture. The authors explain that acculturation can result in different degrees of acceptance. In some cases, the members of the contact groups decide to adopt the greater portion of another culture while giving up most of the older cultural heritage, resulting in assimilation.35 However, acculturation can also lead to adaptation where both original and foreign traits are combined so as to produce a smoothly functioning cultural whole.36 In the case of adaptation the individual may rework the patterns of the two cultures in contact “into a harmonious meaningful whole,” or retain “a series of more or less conflicting attitudes and points of view which are reconciled in everyday life as specific occasions arise.”37 According to Linton, those elements of the minority culture of which the dominant group openly disapproves, will quickly lose their value in the eyes of the minority group and will be abandoned more readily. Linton gives the example of national costumes or practices that are ridiculed by Americans and are therefore given up by ethnic minorities long before other, less obvious ethnic traits are given up.38

However, not all scholars adhere to this distinction of assimilation as the highest form of acculturation. Especially Park’s definition deserves mentioning, as he was highly interested in A Bintel Brief as the object of his research. Park speaks of social assimilation as a form of acceptance of merely the social norms of the host country. He defines social assimilation as ← 21 | 22 →

… the process or processes by which peoples of diverse racial origins and different cultural heritages, occupying a common territory, achieve a cultural solidarity sufficient at least to sustain a national existence. … In the U.S. an immigrant is ordinarily considered assimilated as soon as he has acquired the language and the social ritual of the native community and can participate, without encountering prejudice, in the common life, economic and political. The common sense view of the matter is that an immigrant is assimilated as soon as he has shown that he can “get on in the country.”39

Park’s definition implies that an immigrant can be considered as assimilated as soon as external traits like dress, manner, English pronunciation are indistinguishable from the average American person. Along Park’s definition, intrinsic cultural traits that are not necessarily displayed in public can be retained by the ethnic minority.40

To Milton Gordon, acculturation is a less intense form of assimilation, with integration of the minority into the dominant group as the highest form of assimilation. Gordon defines acculturation as cultural assimilation, which is likely to be the first of the types of assimilation to occur among an ethnic group.41 Cultural assimilation does neither mean marital assimilation, nor the maintenance of primary relationships or private contacts between the host group and the minority. More likely, the minority group will externally assimilate but limit its interactions with the host society to second hand contacts in business situations and in public life. This type of assimilation is likely to occur within the foreign-born immigrant community.42 Among the first American-born generation, however, as Gordon explains, structural assimilation is likely to take place. This implies a large-scale entrance of members of an ethnic group into institutions and cliques of the host society on first hand contact. Gordon sees an “inevitable connection” between structural assimilation and marital assimilation.”43 Through private first hand contact, both groups spend a reasonable amount of time together and closer relationships, like marriage, are more likely to occur. The rising rate of mixed marriages between Jews and gentiles in American society proves this point. It ← 22 | 23 → explains why intermarriage was not seen as a problem during the first years of Jewish immigration, as reflected in the letters sent to the Forverts.

The consequences of assimilation are profound. To Gordon, the price of structural assimilation “is the disappearance of the ethnic group as an entity and the evaporation of its distinctive values.”44 The ethnic group is then fully absorbed by the host society. Therefore, it can be said that as long as the ethnic group exists as an entity, it will never accept all aspects of the dominant culture but rather select certain aspects that can conveniently be borrowed.

In the study at hand, the term acculturation will be used according to Redfield, Linton, and Herskovits as a neutral umbrella term to describe the adjustments made by two cultural groups who respond to their mutual contact. I will describe the adjustments as supported by the Forverts editors and readers before establishing to what degree A Bintel Brief column supported acculturative trends among their readers.

Park confirms the importance of contact between minority group and host society in his Introduction to the Science of Sociology. He writes that even slight contact is sufficient for the transmission of cultural elements, but “the rapidity and completeness of assimilation depend directly upon the intimacy of social contact.”45 Special attention is given to the participation of immigrants in the life of the community he lives in. To Park, “participation is both the medium and goal of assimilation.”46 In order to be able to participate in society, immigrants above all, must learn English. Secondly, as Park notes, the immigrant “needs to know how to use our institutions for his own benefit and protection.”47 Immigrants coming to the United States need to get to know their rights, but also their duties as citizens. Those are two points that have become clear to Cahan as well, as will be shown later. To Cahan, mastering the English language and knowing one’s duties as well as rights as an American citizen are central motifs, as the answers to A Bintel Brief make clear. Summed up, the process of assimilation in Park’s eyes is of psychological rather than biological nature. People grow alike in character, thoughts, and institutions. To Park, assimilation is at least partially possible without intermarriage.48 As assimilation ultimately means intermarriage and the loss of ethnic identity, in Park’s eyes, intermarriage can be avoided ← 23 | 24 → by the ethnic group even beyond the first generation immigrant group without putting its acculturation at stake.

The relationship between host society and minority group appears as another important factor for acculturation in research. A good relationship between both groups encourages the integration of the minority. To Linton, respect towards each other appears to be central in such a situation. In his eyes, “if one group admires the other, they will go through a great deal of inconvenience to be like them, while if they despise them, they will put up with a good deal of trouble and inconvenience not to be like them.”49

Details

- Pages

- 414

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631657591

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653050981

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653975611

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653975628

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-05098-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (November)

- Keywords

- Jewish Daily Forward Ratgeberkolumne Ostjüdische Immigranten Akkulturation

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2015. 414 pp., 1 b/w ill., 18 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG