Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

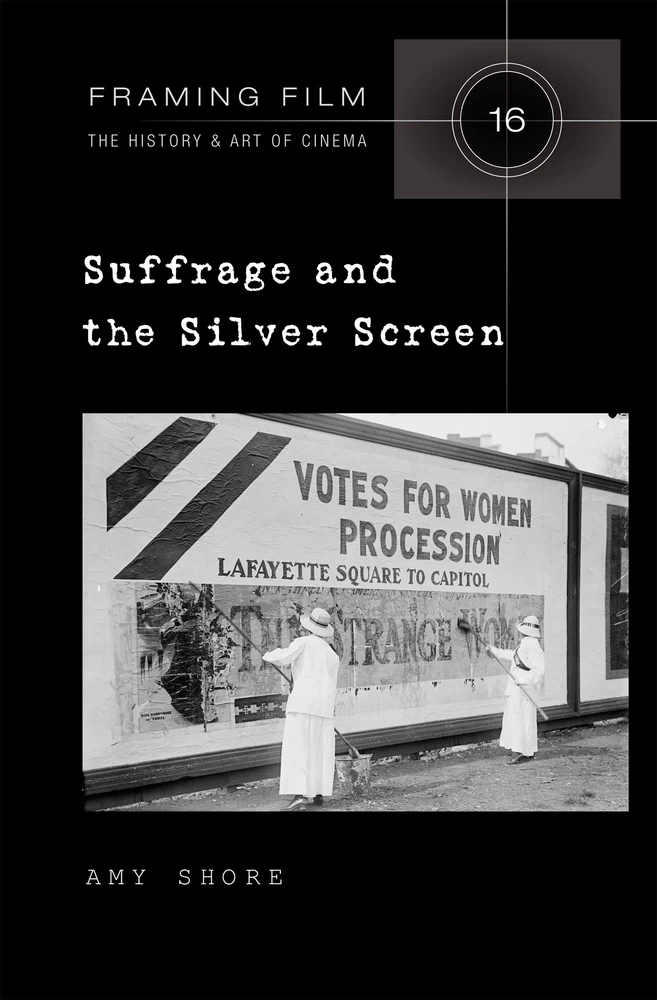

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- Advance Praise

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Reprints & Permissions

- Chapter 1. Suffrage and Cinema, A History of Visual Activism

- Footnotes or Landmarks? The Place of the Suffrage Films in American History

- Chapter Overview

- Chapter 2. Suffrage Saints on the Lower East Side

- Chapter 3. Making More than a Spectacle of Themselves

- Chapter 4. Inventing National Pastimes: Nationalizing Suffrage and Cinema

- Chapter 5. Suffrage Stars

- Chapter 6. What Do 80 Million Women Want?: Answering the Question of Suffrage Desire

- Chapter 7. Producing a National Suffrage Imaginary

- Chapter 8. Suffrage, Cinema and the Emergence of Modern Feminism

- From Natural Right to Social Responsibility: Transformation of the American Woman Suffrage Movement for the Twentieth Century

- A Note on Historical Amnesia

- Chapter 2. Suffrage Saints on the Lower East Side

- Saints and Civic Housekeepers: Suffrage Hagiography in the Progressive Era

- Inventing Saint Susan: Sentimental Identification and Sanctified Spectatorship

- Anointing a Movement, Sanctifying Cinema

- Chapter 3. Making More than a Spectacle of Themselves

- From Street to Stage to Screen: Suffrage Spectacle and Converging Fields of Reception

- A Continuum of Suffrage and Cinematic Activism

- Chapter 4. Inventing National Pastimes: Nationalizing Suffrage and Cinema

- Chapter 5. Suffrage Stars

- Star Systems for Suffrage and Cinema

- Jane Addams and the Desire for Action

- Anna Howard Shaw and the “Heavenly” Female Gaze

- Stars and Fans

- Chapter 6. What Do 80 Million Women Want?: Answering the Question of Suffrage Desire

- A Balanced Approach to Suffrage

- Suffrage and the Man

- 80 Million Women Want ____?

- Chapter 7. Producing a National Suffrage Imaginary

- Negotiating the National: Congressional Committee/Congressional Union

- Your Girl and Mine

- Chapter 8. Suffrage, Cinema and the Emergence of Modern Feminism

- Notes

- Chapter 1. Suffrage and Cinema, A History of Visual Activism

- Chapter 2. Suffrage Saints on the Lower East Side

- Chapter 3. Making More than a Spectacle of Themselves

- Chapter 4. Inventing National Pastimes: Nationalizing Suffrage and Cinema

- Chapter 5. Suffrage Stars

- Chapter 6. What Do 80 Million Women Want?: Answering the Question of Suffrage Desire

- Chapter 7. Producing a National Suffrage Imaginary

- Chapter 8. Suffrage, Cinema and the Emergence of Modern Feminism

- Bibliography

- Index

I am deeply grateful to Peter Lang Publishing for including this book in the Framing Film: The History & Art of Cinema series. Frank Beaver, the series editor, has been an enthusiastic and diligent editor. It is an honor and privilege to have such an esteemed film historian guide me through this process and find my own research worthy to include in this series.

Research for Suffrage and the Silver Screen began during my time as a graduate student at New York University where my dissertation advisor, Chris Straayer, provided invaluable insight and guidance. She was the kind of mentor that one rarely encounters in academia. She embodies the best of the term “educator,” and I am honored to have been one of her pupils.

I am also indebted to Shelley Stamp and Anna McCarthy who gave freely and generously of their time, intellect and energy. The ideas they provided shaped the book significantly; the warmth and support they provided in emails and meetings ensured the completion of the manuscript. Bill Simon has been a true and reliable critic—in the best sense of the word—throughout my entire academic career, particularly in his contribution to this book. Susan Zaeske brought a wealth of knowledge about women’s history and public policy that dramatically re-shaped my thinking about numerous elements of my argument.

While researching the book, I was lucky to work with the finest archivists, librarians, curators and administrators in the country. Rosemary Hanes from the Motion Picture and Television Division of the Library of Congress should be commended for her efforts to identify and catalog films and related materials made by or about the suffrage movement. The scope of this book is a direct reflection of her work, for she is the one who helped me identify the archives where I found a majority of my primary research. In addition, the entire staff of the Manuscripts Division at the Library of Congress helped me cull through volumes of suffrage documents to identify priceless information. Without their guidance, I would surely still be sifting through boxes of letters, memos and scrapbooks looking for relevant material. Martha Sachs, Curator of Special Collections for the Penn State Harrisburg Library, went above and beyond the call of archiving duty to help me secure the best quality reprints of suffrage ← vii | viii → cartoons that are included in Chapter 2. Thank you as well to the archivists at the Museum of Modern Art for helping me access rare film stills.

At SUNY Oswego, where I currently teach, my colleagues and students have introduced me to an entirely new way of thinking about the world of cinema, both in terms of theory and practice. Very special thanks to Bennet Schaber who has been my comrade in the creation of the Cinema and Screen Studies Program and continues to astonish me with his ability to see what no one else can see in a film, phenomenon, student or colleague. My students are my peers at Oswego, and several who served as my teaching assistants have contributed to the completion of this book: Jill Matyjasik, Michael Potterton, Allain Daigle, and Kim Behzadi.

As this is my first book, I have to take this opportunity to thank the many people in my life who have helped me directly or indirectly in my career. A great deal of thanks to the late Judy McInnis, my undergraduate advisor at the University of Delaware. She is the person who first believed in my academic skills, and for that, I am eternally grateful. Thank you to Iris Morales who not only gave me my first “real” job, but inspired me with her activist filmmaking to write this book. A very special thanks to Sy Fliegel, the late Colman Genn, Harvey Newman, Bill Colavito, Frank San Felice and the rest of the gang at the Center for Educational Innovation-Public Education Association (CEI-PEA). My work with CEI-PEA gave me a guiding principle for writing this book: in the end, the book must serve an educational purpose, not my ego.

Thank you to my peers who entered into academia with me, as they are the ones who helped me find what the late Robert Sklar would have called my “intervention” in film studies. Thank you to Janeen LaForce, my graduate school roommate, for those early years of all-night read-throughs of term papers, treks through blizzards to buy our first feminist film books, and road trips to lousy diners in Connecticut. Our friendship helped me maintain enough sanity to ultimately complete this book. Thank you to Roger Hallas for becoming my first friend in graduate school and standing by me through thick and thin. His attentive reading of chapters—both in its original dissertation form and its reincarnation as a book—made this work 100 percent better than it would have been otherwise. Our shared commitment to the study of activist filmmaking made me feel like I had at least one reader out there for whom this book would make a difference.

Last, but by no means least, I must thank my family. My greatest blessing in life is that I was born to two people who would always believe in and support me unconditionally. My father encouraged me to become a feminist and my mother modeled how to live that ideal. My brother provoked me at a young age to take up the position of a feminist—as annoying brothers can do—and now stands beside me as an enthusiastic supporter. ← viii | ix →

Finally, my husband and daughter are the two funniest, most obsessive, adventurous and loving people in my life. I know without a doubt that should we need to march in the streets tomorrow for a cause as great as suffrage, they would be by my side. In fact, they would probably lead the way. To Philip and Maya, my eternal love and gratitude.

Reprints & Permissions

Portions of this book have been previously published in other formats, and I would like to thank the publishers for allowing me to reprint that scholarship in this book. A portion of “Chapter 5: Suffrage Stars,” was published as “Suffrage Stars,” in Camera Obscura, Vol. 21, issue. 3, 63, pp. 1–35. (Copyright, 2006, Camera Obscura. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of the present publisher, Duke University Press, www.dukeupress.edu.) “Chapter 3: Making More than a Spectacle of Themselves,” appears in a modified format in Reclaiming the Archive: Feminism and Film History, Vicki Callahan, Ed., Wayne State University Press, 2010, pp. 309–328. (Copyright, 2010, Wayne State University Press. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Wayne State University Press.) ← xi | x →

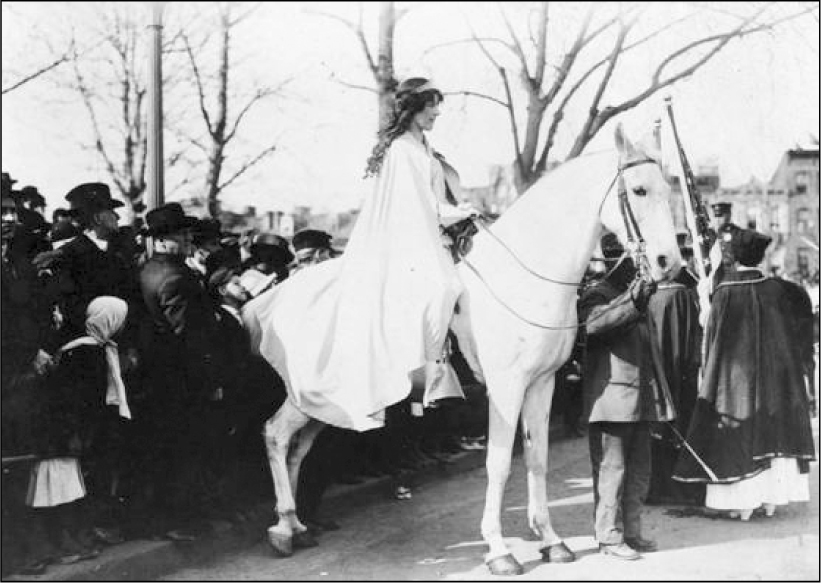

Figure 1. Inez Milholland at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C. (George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsc-00031)

Figure 2. National Woman’s Party picketing the White House, Washington, D.C., 1917 (The Social Welfare History Project: http://www.socialwelfarehistory.com/organizations/national-womans-party/) ← x | xi →

Suffrage and Cinema, A History of Visual Activism

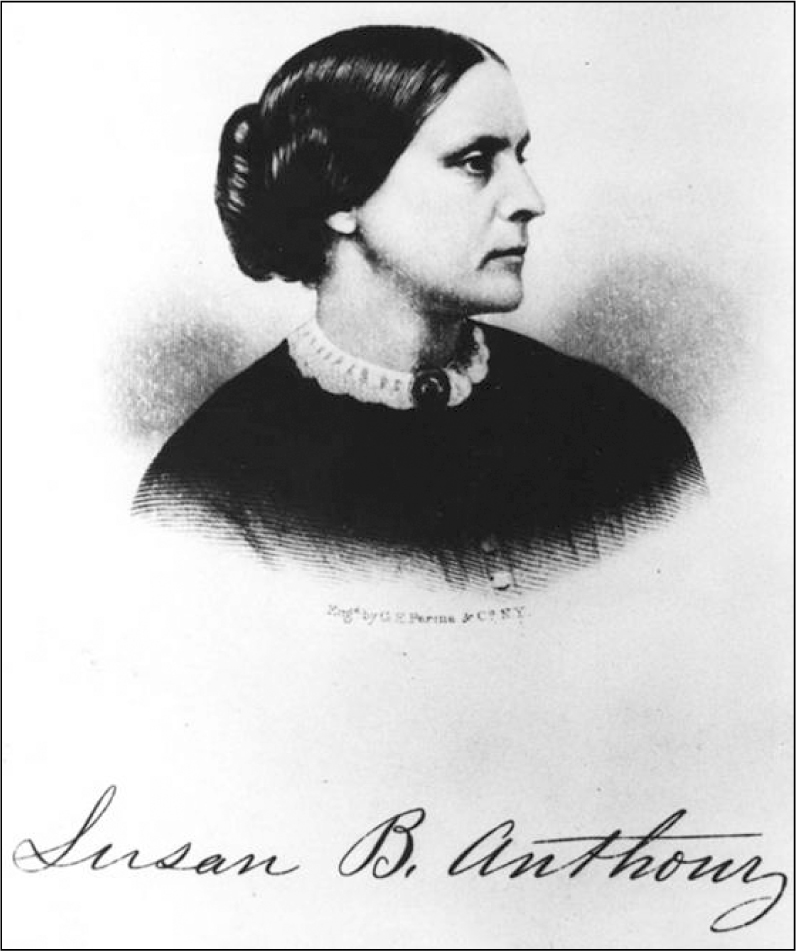

Ladies in white marching down New York City’s Fifth Avenue, Inez Milholland leading the first national suffrage parade dressed as the suffrage “herald” atop a white horse, silent females staring into cameras as they formed the first-ever pickets in front of the White House, images of Susan B. Anthony’s profile in her signature black dress with white lace collar. These are some of the images of the American woman suffrage movement that were circulated in mass during the 1910s to help win the vote by transforming the American woman suffrage movement into a mass movement for the twentieth century. Through posters, plays, pageants and more, the American woman suffrage movement became a modern mass movement by using visual culture to transform consciousness and gain adherents to the cause. As part of this transformation, suffrage organizations produced several films and related cinematic projects in the 1910s. Most were produced in conjunction with a studio, two projects were made for local distribution, while four films were full-length feature productions for national distribution. The works were intended to fulfill the mandate that Harriot Stanton Blatch, leader of the Women’s Political Union (WPU), described in adversarial, yet religious language: “The enemy must be converted through his eyes.”1

This activist use of film was one of the first instances in the United States that a social movement recognized and harnessed the power of cinema to transform consciousness and, in turn, transform the social order. In Suffrage and the Silver Screen, I study how the suffrage movement accomplished this formidable goal. I claim that the cinematic works of the suffrage movement are an important part of the tradition of feminist filmmaking. I also argue that the study of these films as organizing tools can broaden the entire field of feminist ← 1 | 2 → film studies by reuniting questions of feminist filmmaking practice with questions of feminist film theory. Moreover, they extend our understanding of the woman suffrage movement by showing how suffrage organizations mobilized the power of cinematic identification to generate pro-suffrage identities among both local and national audiences. Indeed, suffrage and cinema formed a productive union in the 1910s in which cinema helped generate communities of supporters for the suffrage movement while the movement helped recruit moviegoers to cinema.

Figure 3. Susan B. Anthony circa 1860 (The Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, FRDO 1057: http://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/douglass/exb/womensRights/FRDO131.html)

This productive union between suffrage and cinema is evident in a brief sketch of the works studied in this book. The movement’s cinematic works ranged from lantern slide shows in New York City’s nickelodeons to multi-reel ← 2 | 3 → melodramas shown across the country. They included one of the only “sound” films made during the 1910s—a kinetophone entitled Votes for Women (1911) made at Edison Studios and distributed throughout the Northeast. They also included performances by well-known leaders of both the American and British suffrage movements, including Anna Howard Shaw, President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), Jane Addams, Vice-President of NAWSA and founder of the American settlement house movement, Emmeline Pankhurst, founder and leader of the militant British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), and Harriot Stanton Blatch, head of the WPU. These leaders of the movement were transformed into “suffrage stars,” headlining films distributed as far apart as Boston, New York, Baltimore, St. Louis, Los Angeles, Portland (Oregon), and Montreal.

The suffrage movement also made innovative use of cinematic melodrama to make sentimental appeals to national audiences. Early film critic Vachel Lindsay described one of the melodramas, Your Girl and Mine (1914), as one of the early masterpieces of propaganda films.2 These films turned melodramatic heroines into suffrage heroines and in so doing presented to women across the nation powerful suffrage figures with which they could identify. This process of identification, I argue, was a central strategy by which suffrage and cinema came together to generate followers for the suffrage movement and audiences for cinema.

Footnotes or Landmarks?

The Place of the Suffrage Films in American History

Considering the innovative nature of the films, their focus on social change and their contemporary critical praise, one would assume that they would be among the most-studied works within cinema studies. In particular, one would expect that these works by the suffrage movement would be written about as constituent of the early years of feminist filmmaking. In fact, they remain little more than footnotes in the histories of cinema, feminism and social change. Only three scholars have given the films any measure of study, with Shelley Stamp’s 2000 study of women and early cinema representing the first effort to incorporate the films into a specifically feminist history of American cinema.3

The reasons for the limited study of the suffrage films can be accounted for in several ways. First, all but two of the films are lost. Without the primary object of study—the film—most researchers simply move on to other objects. This is a prevalent problem within studies of early cinema since many of the films either deteriorated or burned because of the nitrate base in their production. In addition, without an appreciation for the long-term value of ← 3 | 4 → films to society—they were seen for the most part as passing forms of entertainment—libraries, museums and other archival sources did not preserve films during the first decades of cinema.

Details

- Pages

- X, 242

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433117817

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453911242

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454192398

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454192404

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1124-2

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (April)

- Keywords

- movement consciousness social order cinema

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 242 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG