Black Queer Identity Matrix

Towards An Integrated Queer of Color Framework

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

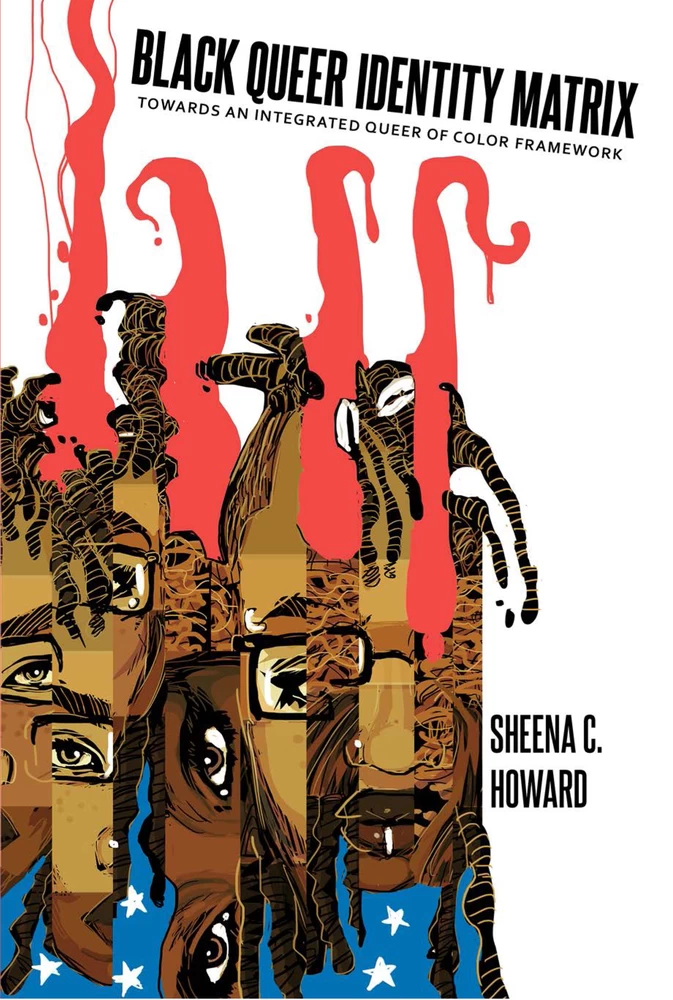

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- Advance Praise

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Intersectionality of Black Lesbian Female Identity

- Chapter 2: Towards an Integrated Queer of Color Framework

- Chapter 3: The Emergence of the Black Queer Identity Matrix

- Chapter 4: Black Queer Identity Matrix: Theoretical Framework

- Epilogue

- Index

Queer has been used as a term to describe homosexual men since the early part of the twentieth century (“Queer”); however, in the mid-to-late-1980s the term began to be redeployed as part of a utopian political project that sought to constitute and position a fluid, sexual subjectivity outside of the “heteronormative” discourses of masculine/feminine gender and homo/heterosexuality.

—Halferty, 2006, p. 125

I’m more inclined to use the words “black lesbian” because, when I hear the word queer I think of white, gay men.

—Isling Mack-Nataf (quoted in C. Smyth, 1996, p. 280)

I have to work hard to be queer. And even then, I do not think I make it. I am pretty comfortable being a lesbian. I mean, I think I get lesbianism, lesbian identity; I do not think queer is as easy to get.

—Whitlock, 2010, p. 81

I have long struggled with the term “queer.” The term has a long evolving history. Although queer studies has the potential to transform the way scholars theorize sexuality in conjunction with other identity formations, the paucity of attention given to race and class in queer studies represents a significant theoretical gap (Johnson, 2001). I went back and forth several times on the title of this volume because of the use of the term “queer” and its lack of inclusion of people of color from its inception.

First, queer is used in this volume to identify anyone on the spectrum of sexual orientation outside of heterosexuality. Second, this book focuses specifically on the Black lesbian community; however, the use of the term “queer” in the title is to indicate that the work done in this book can and should be expanded upon to include any community within the queer community. Thus, it is my hope that from here, specifically racial minorities on the queer spectrum, use this as a vehicle to studying, exploring, and analyzing their own communities through an intersectional lens or through a queer matrix lens.← vii | viii →

When I was little, around the age of six or seven, I remember the word “queer” being used to describe anyone who did not conform to heterosexuality; however, it was used in such a derogatory and insulting way. I feared to ever be called a “queer”—it sounded like one of the worse things to be called. When I first learned of queer theory during my graduate studies at Howard University, I immediately cringed at the use of the word. It was so embedded in my cultural memory as a term loaded with negative connotations. It became clear to me that scholars and activists had attempted to reclaim the term and use it as an inclusive word to describe nonheterosexual communities under one umbrella. Upon accepting the idea of “queer” as an inclusive term to describe sexual minorities, I again took issue—and still take issue—with the lack of racial inclusion within the body of literature around queer theory. It became evident to me that queer theory emerged from a Eurocentric platform in which the LGBTQ of color community was not taken into consideration, similar to the feminist movement, in which Black women felt (and were) excluded. It is because of this that I have struggled with embracing the term “queer” and using it as a catalyst or starting point in this volume. Ultimately, I have come to believe that queer theory has indeed led to the emergence of this volume, for without my disappointment in the queer theory paradigm, I would not be compelled to move scholarship or discussion toward a more integrated theoretical or conceptual framework. I view the work in this volume and the ultimate emergence of the Black Queer Identity Matrix as a voice within queer theorizing that offers a means of resistant expression within a given social and cultural context.

The Black Queer Identity Matrix represents research and theory that includes the experiences and ideas shared by ordinary Black, lesbian women who provide a unique angle of vision on self, community, and society. Black lesbian women are positioned within structures of power in fundamentally different ways than White queer men and women. Black lesbian organizations have faced and continue to face pushback from both the White gay community and the White lesbian community across the country. The gay rights movement is not only for gay white men. This seems to be self-evident; however, so often the visibility of the Black lesbian community is limited especially as it relates to representation within the media and politics. Thus, I would like to see a Black LGBTQ framework that re-centers the African American standpoint—that is, the historical, social and cultural underpinnings of the African American experience—as the starting place for theory and discussion through a more inductive social scientific approach as opposed to creating a theory that stems from a Eurocentric platform.← viii | ix →

I realize that this book posits a theoretical framework that deals specifically with a minority group and the common (or not so common) experience of said group, and with that comes the immediate criticism of “essentialism” or “anti-intellectualism” from scholars. I write this book in preparation of that criticism, knowing that the fear of that criticism is much less important than the significance of this work. For any work focusing on the collective of a minority group faces the critique of essentialism.

References

Halferty, J. (2006). Queer and Now: The Queer Signifier at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre. Theatre Research in Canada, 27(1/2), 123–154.

Smyth, C. (1996).What Is This Thing Called Queer? In D. Morton (Ed.), Material Queer: A LesBiGay Cultural Studies Reader (pp. 277–285). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 107

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433122330

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453911891

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454199564

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454199571

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433122323

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1189-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (September)

- Keywords

- necessity baseline minority group proposal

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 107 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG