The Souls of Yoruba Folk

Indigeneity, Race, and Critical Spiritual Literacy in the African Diaspora

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. A Call … to the Souls of Yoruba Folk

- Chapter 2. Theories of Diasporic Indigeneity and Black Feminisms: Living and Imagining Indigeneity Differently

- Chapter 3. In Dialogue With the Souls of Yoruba Folk: Engaging a Yoruba Worldsense—Overtly Christian, Covertly Yoruba

- Chapter 4. At a Crossroads: Esu, Language, and the Politics of Critical Spiritual Literacy

- Chapter 5. “They’re not always right but they’re older”: The Polemics and Paradoxes of Seniority in Yoruba (Indigenous) Culture

- Chapter 6. The Response: “Ohun ti o wa leyin offa, o ju oje lo” [What follows six is more than seven]

- Chapter 7. An Open Letter to Teachers: Pedagogical Implications and Applications of The Souls of Yoruba Folk

- Bibliography

- Series Index

| ix →

“A child doesn’t belong to the father or the mother: A child belongs to the ancestors.” This ancient African proverb bears cosmological witness and offers a scholarly imperative to (re)member our existence as Black people and the central work of providing education that engages our histories, our present conditions, and our futures. But this call is also a recursive one: It is a call to look inward, to look backward, and to look forward for understandings of how to move in ways pleasing to those on whose shoulders we stand. The Souls of Yoruba Folk: Indigeneity, Race, and Critical Spiritual Literacy in the African Diaspora brings together all of these dimensions in an important example of what Adefarakan describes as a “personal and political effort to de-pathologize African spirituality and shift the popular imagination (African and otherwise) from its profound reliance on re-circulated colonizing scripts about African Indigenous spirituality, to ones that are affirming, nuanced, and grounded in an African-centered, feminist, and anti-colonial politic.” Locating this work in the conceptual tradition of W. E. B. DuBois’ notion of double-consciousness, this text raises and inquires into the important, often contradictory, and always complicated ideals that DuBois raised for the African in America, namely the unreconciled (and possibly unreconcilable) nature of the souls of Black people who live in diasporic spaces, spaces that too often render us inferior through dominance ← ix | x → and oppression of our minds, bodies, and souls. Here, Adefarakan adds to the spiritual and scholarly legacy set by DuBois, pointing to the ways that colonization within Western thought have produced scant studies in social sciences, education, and cultural studies by or about African spiritualities in diaspora. More specifically, as one of the most popular expressions of Indigenous spirituality in the African diaspora, Adefarakan shines a light on the soul of Yoruba folk as a nuanced “diasporic indigeneity.” In important ways, she extends DuBois’ notions and our understandings of double consciousness and spiritual strivings to ones that are not solely bound by physical space or location, but as realities in diasporas as well. I was particularly struck by ways that the Yoruba elders and community member participants in this text made sense of being Yoruba people who often overtly pushed down or masked Yoruba spirituality, religion, and traditions while simultaneously lifting up Christianity and/or Islam as their “only” forms of religious practice in Canada. What we learn in The Souls of Yoruba Folk: Indigeneity, Race, and Critical Spiritual Literacy in the African Diaspora helps us to better understand these seemingly contradictory realities and points us to the serious consequences and costs of being Black in diaspora(s), where forgetting is often encouraged, “necessary,” and a political strategy of survival.

Each chapter of The Souls of Yoruba Folk: Indigeneity, Race, and Critical Spiritual Literacy in the African Diaspora is one that causes you to pause as Adefarakan deftly turns our taken-for-granted and often narrow lenses of spirituality and helps us to open them wider, especially in her study of those often lumped into the collective “African,” or “American,” or “indigenous” and extends it to include the “Nigerian,” the “Canadian,” and the “Yoruba.” In doing so, we come to see the powerful nature of what it means to be spiritual in the African diaspora a little bit more clearly and expansively. In the final chapter of this critical work, Adefarakan pens a letter to teachers, putting forth moral and ethical dilemmas and imperatives for our work of teaching children with Indigenous African spiritualities in mind and heart. With passion grounded in her research as well as her personal identity as a Yoruba woman teacher and mother, she argues the need for children in general and Black children more specifically to have deep spaces within the school context to develop skills of critical spiritual literacy. As I have argued in my own work, such spaces and skills, by necessity, must be centered on helping students “learn to (re)member the things they’ve learned to forget” in order to make informed decisions about the direction and desires within their spiritual identities and lives. ← x | xi →

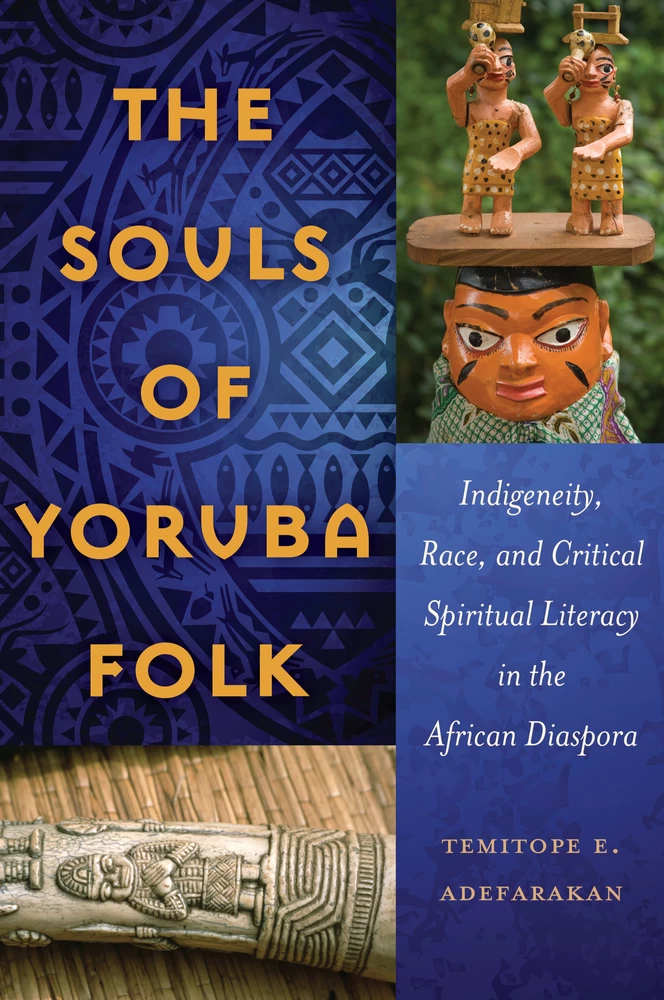

I want to say a few words about the cover images found on The Souls of Yoruba Folk: Indigeneity, Race, and Critical Spiritual Literacy in the African Diaspora. Adefarakan selected the beautiful gelede of the Ketu-Yoruba people. The gelede performance is an important and sacred ceremony that pays homage to the spiritual powers of women, especially the elder women known by the Yoruba as “our mothers.” Through performances of music, dance, song, and the actual mask and dress, the gelede maskers appeal to and encourage the community and our mothers to use their extraordinary powers for the well-being of the society. Analytically, this performance can be seen as a form of commentary on social matters of the community that is at once secular and sacred. And this powerful book that the reader holds in their hands is an echo of the same spirit. Adefarakan helps us to understand the nuances of indigeneity, race, and spirituality amongst the Yoruba in Canada. In a profoundly endarkened feminist way, she also encourages us to (re)cognize the gifts of our mothers and to (re)member that they are, as the Yoruba believe, the “owners of the world.” Thus, we must (re)member not for ourselves: We must do this for our children. The Souls of Yoruba Folk: Indigeneity, Race, and Critical Spiritual Literacy in the African Diaspora is a brave text. May we listen carefully to the wisdom of the ancestors as they teach us through this important volume.

Cynthia B. Dillard, Ph.D. (Nana Mansa II of Mpeasem, Ghana, West Africa)

Series Editor, Peter Lang, Black Studies and Critical Thinking Series—Spirituality and Indigenous Thought

| xiii →

Modupe Olorun Eleda mi [I give thanks to God my Creator].

To the Most High Olorun Olodumare, the Divine Supreme Being and Creator of our Universe, I am grateful for the strength and courage endured through the years it took to journey The Souls of Yoruba Folk, and especially for the gift of my son along the way. I am grateful for the many people sent during this time who joined me on the journey, at different points, for different reasons and purposes. Some are still with me, while others have diverged to take their own paths. I give thanks to have experienced their presence in my life and the imprints they have left both in my life and this book.

I thank the 16 Yoruba community members for their indispensable contribution, who, upon agreeing to participate in this project, made it rich and unique. This book could not have happened otherwise: Thank you for having the courage to voice your experiences and for sharing them with me. I am also grateful to Toronto’s Yoruba Community Association (YCA), whose staff and members have been extremely supportive.

What is now The Souls of Yoruba Folk: Indigeneity, Race, and Critical Spiritual Literacy in the African Diaspora began as my doctoral dissertation; hence, I remain grateful to my thesis committee: Dr. George Dei, my thesis supervisor and mentor, I thank you for the staunch critical support and unwavering belief in the importance of this topic. Dr. Tara Goldstein, I am eternally grateful ← xiii | xiv → for your scholarly expertise and overall support primarily because your door was always open. Never did you doubt that I could do this and your kind and encouraging words always kept me going. Dr. Martin Cannon, thank you for your support and keen ability to critically engage my work in such a way that it strengthened my scholarship and challenged me to think about research from various perspectives, especially from that of the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island.

Dr. Cynthia B. Dillard … where do I begin? A woman who initially was the external examiner for my doctoral dissertation, I am ever so grateful for your sistership and mentorship in this work, as lived praxis. Simply put, this book would not have been possible without your patient support and confident faith that it would happen. And it did. Mo de dupe [So I thank you]. Your scholarship has been indispensable as an exemplar of writing about spiritual life in the academy, and I continue to learn and grow, taking cues from your life as an African feminist academic grounded in our Indigenous spirituality.

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 169

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433126093

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453915837

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454195634

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454195641

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433126086

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1583-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (July)

- Keywords

- canadian immigrants canadian imigrants diaspora spirit multiculturalism

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2015. XVI, 169 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG