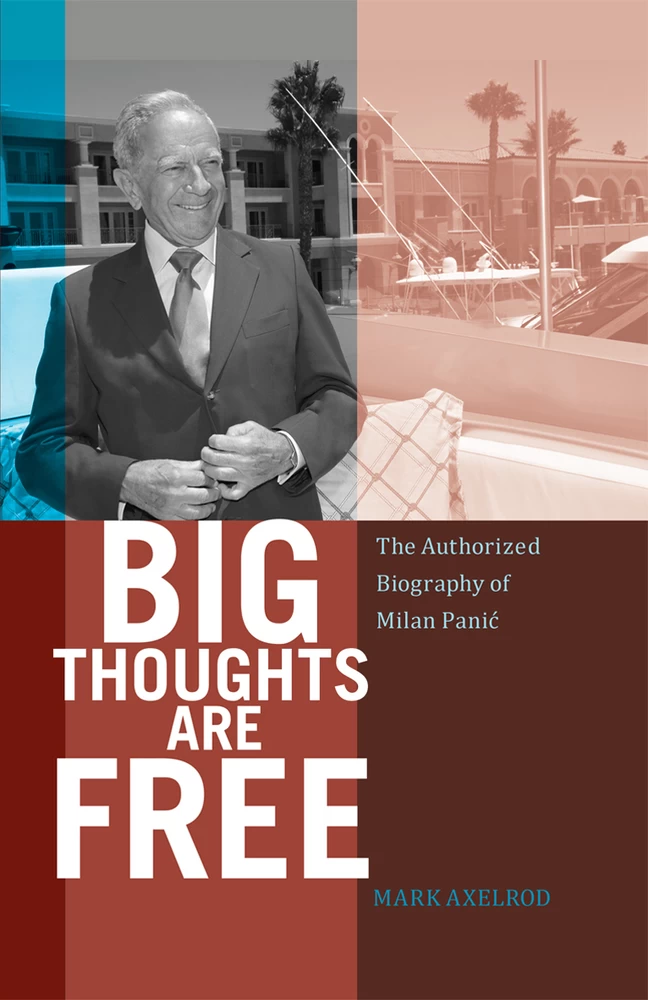

Big Thoughts are Free

The Authorized Biography of Milan Panic

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- CONTENTS

- Preface

- Foreword

- Chapter 1. A Day in the Life of Milan Panić

- Chapter 2. A Yugoslavian Context (1918–1929)

- Chapter 3. Belgrade, The White City (1926–1929)

- Chapter 4. A Belgrade Life, War, and the Aftermath (1929–1941)

- Chapter 5. Coming to America

- Chapter 6. Family Life and Times of Milan Panić

- Chapter 7. The Rise of ICN

- Chapter 8. The Rise of Milan Panić

- Chapter 9. American Politics 101: The Bayh Influence

- Chapter 10. The Call to Duty: Prime Minister and the Milošević Connection

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Appendix

- Index

| ix →

The term “Renaissance man” has been liberally used to connote people with many talents or areas of knowledge. In fact, a more accurate definition relates to people who have acquired a profound knowledge in broad-based areas of life.

The above difference in definition is significant. Although many people have many talents, most are masters of none. Such people may more closely fit the definition of dilettante rather than Renaissance man.

The people of any age who acquire and demonstrate a profound knowledge in the intellectual, physical, social and artistic dimensions of life are indeed a select few. In the past, individuals like Zhang Heng, Isabella d’Este, Leonardo da Vinci, Akbar the Great, Benjamin Franklin, and Isaac Newton are prime examples. Their talents and knowledge not only covered many areas, their impact in those areas was influential, if not profound.

It is more difficult to categorize modern Renaissance men since one’s impact in a particular area takes time to gestate. But likely prospects include Winston Churchill, Dr. Maya Angelou, and Steve Jobs.

After reading Mark Axelrod’s provocative and passionate account of the life of Milan Panić in Big Thoughts Are Free, I venture to add an authentic example of another modern Renaissance man. In Milan Panić we discover a multi-faceted man whose impacts in the intellectual, physical, social, and artistic areas of life know no bounds. ← ix | x →

As an intellectual, Milan Panić headed the scientific team that discovered, developed, and produced Ribavirin, a drug that has saved millions of lives through its treatment of hepatitis C.

In the physical realm, Milan Panić was a junior champion in biking and went on to become a member of the Yugoslavian national biking team.

As a man of the world, Milan Panić served as prime minister of the Federal Republic of Serbia. He was the first American citizen to hold such a high office for another nation.

And in the arts, Milan Panić has been a transformational leader in the world of opera and ballet.

What are innate attributes and special circumstances that nurtured the development of a person like Milan Panić so that he was able to transcend the traditional boundaries of human endeavor? In telling the story of a true Renaissance man, Mark Axelrod’s Big Thoughts Are Free answers this question and, in doing so, brings the remarkable story of Milan Panić to life. It is an important story that needs to be told.

Dr. James Doti,

President, Chapman University

| xi →

I never knew who Milan Panić was prior to being introduced to him through the office of Dr. James Doti, president of Chapman University. I had heard some rumors about him. That he was “difficult to deal with,” had a very clear “mind set,” was prone to “getting his way,” et cetera, which, for a long-time CEO of a major international corporation, wouldn’t be unusual. Somehow, those things didn’t dissuade me from wanting to meet him and discuss the possibility of writing his biography, which, as I was to discover, would be the fifth attempt at writing one. One could argue about what happened with the other four and go into a long narrative about that; needless to say, for various and sundry reasons, they didn’t work out.

My first meeting with Milan Panić and his main assistant Alexandra Novak, was, as I recall, not unlike what I had anticipated. Milan Panić was not merely a spry 83-year-old, but a very energetic 83-year-old. As we discussed the possibility of my writing his biography, the word “laconic” came to mind. Terse, to the point. Whether that would be in business or politics or in closing a book deal, Milan Panić was to the point. Regardless of the fact there were four previous attempts at writing his biography, he knew what he wanted, and when he wanted it, and he was direct about telling me. At one moment in our discussion he said he was very “opinionated.” I responded, “So ← xi | xii → am I, so I imagine we’ll get along well together.” And, to a great degree, we have.

One of the things that impressed me the most about Milan Panić was his notion of fairness. In principle, we had agreed to a timeline and fee for writing the biography, but, of course, it had to be “legitimized” by his attorneys. The original agreement was about one page long that stipulated my responsibilities, their obligations, deadlines, and fees; however, after the attorneys got the agreement it became a nine-page, single-spaced discourse in narrative obfuscation that spanned almost five months of negotiation. Very annoying. My first response to reading it was to recall the famous line in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 2 (1591) in which Dick, the butcher, a character few can ever remember, utters the immensely unforgettable line, “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” To which Cade replies, “Nay, that I mean to do. Is not this a lamentable thing that of the skin of an innocent lamb should be made parchment? that parchment, being scribbled o’er, should undo a man?” (Act 4, Scene 2, pp. 71–78).

Of course, everyone since has taken the line out of context, in that it was Dick’s idea to kill all of England’s lawyers as his contribution to the faux revolutionary Jack Cade who, by his response, was a firm believer that lawyers were mere paper shufflers whose raison d’être was to make life rather miserable for the common folk. When, in a subsequent meeting, I quoted the Shakespeare line, Milan Panić, who had not read the contract and was out of the country when I received it, laughed. At a later encounter I had with Panić about attorneys he actually tossed in accountants as well. So it goes.

I then told him that based on a reading of the contract by two attorneys (one of whom was my brother) and an accountant the overwhelming consensus was not to sign it, for a number of reasons that I was not articulate enough to enumerate. I did mention, however, that the line in the contract that read that I would submit a “professionally written biography” that was of “artistic taste” begged numerous questions. My response caused Milan Panić to laugh as well, but as I said before, Milan Panić wanted to be fair. I understood that, based on his previous experiences with writers who, for one reason or another, wrote something other than a biography, his attorneys wanted to be cautious and prudent about his affairs, but I also told him that we had first met almost three months earlier and the contract writing had taken almost a month to close and was still in flux. Since we were on a tight deadline (his 85th birthday being the point of destination) I said that we had wasted a lot of time already, and although even five months later* there was no contract in hand, it did ← xii | xiii → bring up the notion of fairness, and it brought up something else; namely, Panić’s almost reverential attitude towards getting things done.

And that brings me back to the word “laconic.” Without hesitation he said two things: 1) Have your attorney/accountant strike out anything he doesn’t like and send it back, and 2) I’ll pay you something upfront so you can get started immediately. I asked him what he meant by “immediately” and he responded, “right now.” I said, “Can I go home first?” to which he reservedly laughed. In other words, part of him literally meant, “right now,” which was totally in keeping with Milan Panić’s character. Eventually, of course, we finally negotiated a contract without killing any attorneys, but the entire sequence of events was very revealing about Milan Panić and the way he liked to get things done, and given the way I liked to write, the process was mutually acceptable.

Unfortunately, allowing attorneys to settle things, especially rather simple things, can create problems where none were intended, since about six months later the legal team still hadn’t come up with a contract that was equitable. One might have thought they were re-structuring the bankruptcy of the Ford Motor Company and not putting together a rather simple “work for hire” contract. Be that as it may, it essentially put me six months behind a 24-month project that should have taken 36 months to finish with a deadline that was fast approaching. Finally, a contract was signed. But I digress.

Since that first meeting, Milan Panić and I had met multiple times: in his office, in his home, on his yacht, and each time we met I learned something new, something insightful and always something refreshing about the man. For the most part, his candor was exceptional, and even though there were subjects he was reluctant to talk about (e.g., the war years, his son’s death) we were able to find a time and a place to discuss those things that were difficult to address.

Unlike Panić’s previous “biographers” Gali Kronenberg and Manojlo Vukotić, I had been writing for over four decades and had published extensively in the United States, Europe, and Latin America. Though I appreciated the attempts that both of those writers made at writing his biography, I also saw the flaws in those attempts. What both of those writers had in common was their inability to get the facts straight and, failing that, they had decided, in Kronenberg’s case, to write fiction, and in Vukotić’s case, to speculate on the truth. I had no intention of doing either.

Whereas Kronenberg decided, for whatever reason, to write a “biography” that was less a biography than it was a fictional children’s story, and Vukotić ← xiii | xiv → decided to write a “biography” that relied less on research and more on conjecture, I had decided to give a backstory to Milan Panić’s life before approaching his biography. To that end, I believe there needs to be a context for Panić’s life, and that is why I begin with an overview of Yugoslavia and Belgrade after 1914 and before 1929—the time of Panić’s birth—before writing about what happened subsequent to his birth. I think it is important to understand the background of Yugoslavia and the socio-political and cultural aspects of the country, since a lot of what transpired in those years (and after) would have a major impact on Panić’s formative and later life.

So, where does one begin talking about the life of Milan Panić? I believed there needed to be a historical, cultural, and political context for his life, and so with that in mind I divided his life into three main parts: The Yugoslavian Years (1929–1956); the American and Entrepreneurial Years (1956–1992); and the Political and Entrepreneurial Years (1992–Present). But before that begins, I thought it would be of interest to include what I call “A Day in the Life of Milan Panić.”

* The actual contract wasn’t agreed upon until January 8, 2013.

| 1 →

·1·

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF MILAN PANIĆ

To get an immediate appreciation for the character of Milan Panić, it might do well to take a day in his life as a kind of point of departure. To do that, I thought a trip I took with him and others to Avalon on his yacht, Bellissima, would be a good place to begin to give one a sense of who Milan Panić is, especially outside the office, and his approach to life.

On the particular day in question, Panić awoke between 6:30–7:00 a.m., after which he rode his normal 30 minutes on the stationary bike, an exercise that had its beginnings when he was a youth in Belgrade, and had contributed to his athletic excellence and been a part of his life ever since. Afterwards, he showered and came downstairs with his son, 12-year-old Milan Jr., and the two of them had breakfast together, though his was “light.” As he told me, “I totally changed from eating a very heavy European breakfast to having a very light breakfast. I have coffee for breakfast, a Diet Coke, vitamins, and, sometimes, a little Cheerios, the ones for the heart.” One may argue about the relative healthfulness of his breakfast, but one cannot argue about his fitness, which, as I was to discover, is better than a lot of men 30 years his junior. Breakfast over, he and Milan Jr. played a little bit before preparing food for his guests that he had invited to the ship, then they went to the store to pick up a little more food before coming to the boat. ← 1 | 2 →

Details

- Pages

- 319

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453914472

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454192640

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454192657

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1447-2

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (July)

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG