Beyond Borders

Queer Eros and Ethos (Ethics) in LGBTQ Young Adult Literature

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

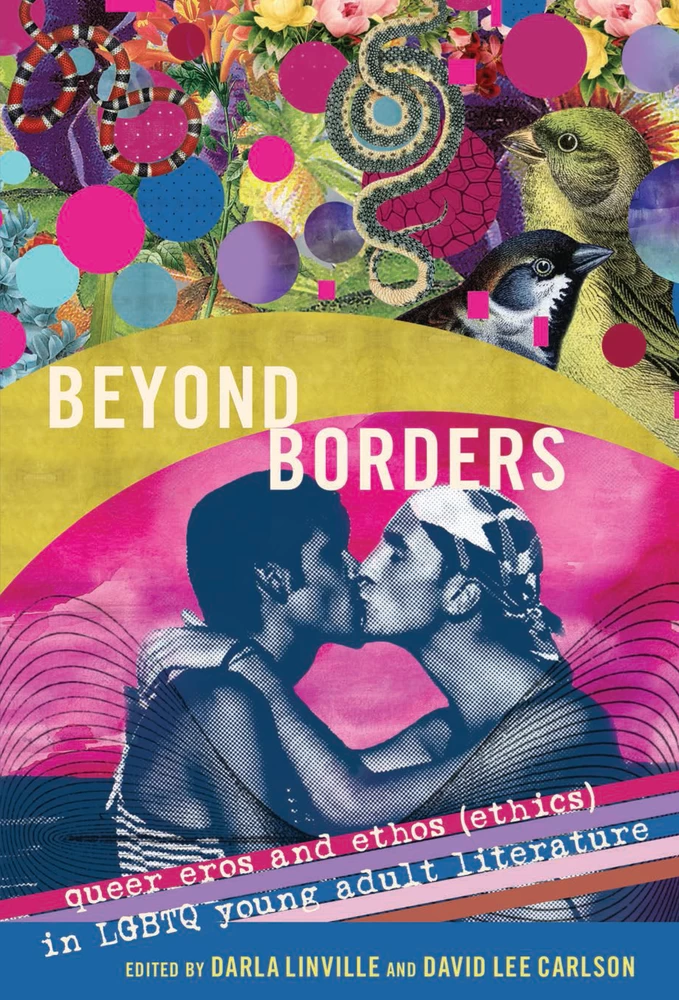

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword: Telling New Stories

- Section One: Queering Theory

- Chapter One: Out of the Closet and All Grown Up: Problematizing Normative Narratives of Coming-Out and Coming-of-Age in Young Adult Literature

- Chapter Two: Queer Recognition and Interdependence: LGBTQ Young Adult Literature and the Contemporary Moment

- Chapter Three: Billy Elliot, Swan Lake, and Shifting Queering Effects

- Chapter Four: Friendship as/and Shared Enmity

- Section Two: Queering Identities

- Chapter Five: At the Intersections of Identity: Race and Sexuality in LGBTQ Young Adult Literature

- Chapter Six: Destabilizing the Homonormative for Young Readers: Exploring Tash’s Queerness in Jacqueline Woodson’s After Tupac and D Foster

- Chapter Seven: After Homonormativity: Hope for a (More) Queer Canon of Gay YA Literature

- Chapter Eight: Creating Spaces of Freedom for Gender and Sexuality for Queer Girls in Young Adult Literature

- Section Three: Queering Curriculum

- Chapter Nine: Exploring the Tensions of Reading LGBTQ YAL With Higher Education Student Affairs Professionals

- Chapter Ten: Reading YAL Queerly: A Queer Literacy Framework for Inviting (A)Gender and (A)Sexuality Self-Determination and Justice.

- Chapter Eleven: Queer Literacies: A Multidimensional Approach to Reading LGBTQ-Themed Literature

- Chapter Twelve: Openly Straight: A Look at Teaching LGBTQ Young Adult Sports Literature through a Queer Theory Youth Lens

- Afterword to Beyond Borders: Queer Eros and Ethics in LGBTQ Young Adult Literature

- Contributors

As an English teacher and a public and school librarian, we began our careers listening to young people search for stories that they needed or wanted to hear. Many sought adventures, superhero action tales, or romances. Just as often young people search for stories that help them figure out who they are, that reassure them that they are not the only one, and that allow them the opportunity to explore various ways of being in the world through the eyes of a character in a novel. As adults working in these positions we often try to steer young people to good books—those considered to be literature as well as those stories that support messages we want young people to get. The message we want to send often depends on the situation that the young person is in, as well as the beliefs we hold as adults. Young adult (YA) publishing has to contend with this fraught context—to be literary and chaste enough to appeal to the adults charged with promoting it to teens (English teachers, school and public librarians, and parents) and to be accessible and relevant enough to appeal to teens as a direct audience. And, of course, what is meant by each of these categories is quite subjective, with tastes in both adults and teens subject to change.

As queer theorists, in this collection we ask if young adult literature can do even more than represent works of literature or entertainment. A theme that runs through the chapters in this volume reminds readers that lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, questioning, intersex bodies are still too often invisible in adolescent spaces—schools, church groups, afterschool activities, sports, online communities—and that when these young people identify themselves they too often ← VII | VIII → face violence and harassment. Many authors in the collections talk about the dire statistics for LGBTQQ youth, and certainly that is a consideration for thinking about why we need better and more varied representation. At the same time there are more images of LGBTQQ youth in popular culture, media, and even in gay-straight-trans alliances in schools, and sometimes these images work to be inclusive of certain queer bodies but not others, or propose a “correct” way to be queer (McCready, 2004; Rasmussen, 2006). Within this discursive and material context, the chapters in this volume ask readers to imagine other spaces, representations, ways of being, identifications, and inclusions of LGBTQQ characters and stories. These authors ask what other representations of queerness and adolescence might exist. And what does queering adolescent literature offer to young people and the adults who work with them? And what is queerness about, beyond sexual practices? What other possibilities exist besides gay marriage or suicide for queer or gender-creative (Miller, in press) teens?

This collection offers a new theorization of young adult literature that looks at questions of ethics and Eros as well as classroom practices, all firmly grounded in queer theory. This volume compiles essays from various authors exploring the queerness of young adult literature that contains lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, and questioning characters. It also contains several examples of ways to approach teaching these novels with a queer approach in the secondary English Language Arts classroom. It contains essays that use theories in novel and creative intersections with literature, although many opportunities still exist to theoretically examine this area. We propose this collection as a beginning of this conversation.

We have found in talking with young people that they often feel like Bobby, in !Out of the Pocket (Konigsberg, 2008), when he expresses frustration about being known as “the gay kid.” Like Bobby, teens we know are out and proud of their LGBTQ identities, but also want to be seen as someone with other facets, interests, and talents, and to be identified by their sexual or gender identities only when that is relevant to the setting. They do not want to hide their sexual or gender identities, nor do they want their other characteristics to be subsumed by those identities. Similarly, authors of teen novels with LGBTQQ characters have worked toward providing images of LGBTQQ youth who are queer or gender creative, but whose storylines incorporate that factor as a character element rather than the central plot problem. This expansion of the images of LGBTQQ characters in young adult literature is welcome and laudable, and all the contributors to this collection would, we think, raise a toast to the young adult authors and publishers responsible for expanding and complicating this genre. At the same time, we encourage authors and publishers to keep pushing the edges to make these characters more representative of other young people whose experiences are less often found in popular culture: immigrant or undocumented youth, trans youth, non-White youth, and non-middle-class youth. As is pointed out in the chapters ← VIII | IX → in this volume, young people and the adults who work with them seek images that counter stereotypes and offer possibilities for identities beyond the current boundaries.

QUEERING THEORY

The problem with boundaries and stereotypes is that they sanitize and uncomplicate complex relationships. The notion that intimate friendships and amorous bonds can be messy endeavors forms the basis for this section. Although each of the authors employ different epistemologies and theoretical threads, each of the authors in this section highlights the complicated nature of the struggles within oneself to be in relation with others. Hence, the ethics in Eros remains an elusive, confusing, and chaotic course that is fraught with uncertainty, risk, and strife. As Benozzo, Koro-Ljungberg, and Adamo state, “Human bodies move. They do not only dance according to the rules” (current volume, p. 45). A vital aspect of this messiness is the profound sense of vulnerability that characters in LGBTQ novels feel about their sexuality and desires. Each of the authors explore this vulnerability in different ways, exposing it as either a gift of “shared estrangement,” fluidity, and recognition, or as an opportunity to govern and control another. Eros within the ethical relationship with another can function as either a gift of inclusivity and involvement or as a means to control another person based on one’s wishes to maintain normative standards and boundaries. Therein lies the continual and constant ethical struggle of the Eros between people. A profound hope exists in each of these chapters. A liberatory tone echoes throughout the section in that the possibility for ontological fluidity generates a nominal freedom that ferments in the uncomfortable messiness of human relationships. A freedom that takes work, that requires historical analysis of taken-for-granted notions such as development and adolescence, and willful shifts in perceptions that clean up the space for individuals (specifically LGBTQ) to dance, to sing, and to be.

QUEERING IDENTITIES

The chapters in the Queering Identities section complicate who we think of as the LGBTQ teen character. Each of these chapters examines storylines in which characters are exploring their understanding of non-heterosexual or gender nonconforming identities, but this exploration is not the central crisis of the story, or is complicated by other identity explorations. These characters are negotiating identity in relation to other ideas about themselves that are important, and exploring how they fit within the various identities that define their lives. Homonormativity ← IX | X → may require us to think of LGBT as white and middle class, and characters of color as straight, as if the communities were mutually exclusive. However, they are not, and representations of the intersectional spaces where actual young people reside are helpful for those looking for reflections of themselves in the pages of a book. These chapters help complicate the stories of queer characters, girls, characters of color, and the families in these characters lives. The stories represented here weave a richer tapestry of representation of who LGBTQ people might be and how they fit into communities.

Sybil Durand examines the story of Ray, or Liu Rui-yong, in Paul Yee’s Money Boy. Ray’s family moved to Canada from China when Ray was a young boy, and he represents what Blackburn and McCready say is a growing segment of LGBTQ youth in the U.S. and Canada, that is, “non-White, nonnative speakers of English who understand their sexual identity from a non-Western or, at the very least, dual cultural frame of reference” (Durand, p. 73, citing Blackburn & McCready, 2009, p. 228). Ray’s goal is not to escape his Chinese neighborhood in Toronto or to assimilate into White gay support group space, where his immigrant status makes him an outsider as well. Durand teases apart the conflicts Ray experiences in his identifications, the distaste he feels for the effeminate Chinese gay man that he recognizes, and his search for a place in which both his Chinese identity and his gay identity can coexist with his sense of his own masculinity. Her examination of these tensions using intersectionality as a framing theory explores the ways that Ray’s Chinese identity, within the context of Toronto, comes with various cultural expectations, both from other Chinese Canadians, including his family, and from the “Westerners” who make up the crowd at school who have become supportive of another, popular boy who came out this past year. His negotiation of the identities immigrant, gay, son, Chinese, and teen offers rich observations about the ways these identities do not exist on their own but each exert influence on Ray’s life in a dynamic tension with other identities. This text, and Durand’s analysis of it, offer many new possibilities for young people looking for representations of non-White queerness and for teachers looking for stories that tell more complicated narratives about how we each make a place for ourselves within the communities in which we live.

Jill Hermann-Wilmarth and Caitlin Ryan also explore intersections of identity in the middle grades story After Tupac and D Foster by Jacqueline Woodson. They focus on the interactions of a secondary character, Tash—the older brother of one of the main characters—with other characters. The young girls who narrate the story offer insight about Tash’s place in the family, in the neighborhood, and in his community of non-heterosexual and sometimes gender nonconforming young men of color. They demonstrate the ways that Woodson makes a queer character central to the story by having other characters show acceptance, love, and approval for Tash and his gender performance. The main characters offer reframing or censure for ← X | XI → those who do not treat Tash right, and enable readers to come to understandings about Tash’s experiences of injustice. Hermann-Wilmarth and Ryan demonstrate this queered narrative in “the ways that Woodson makes positive language around queer identities available, relies on conceptions of family that don’t depend on heteronormative perspectives, and shows queer people as existing in larger communities, both predominantly queer and predominantly straight” (this volume, p. 86). Hermann-Wilmarth and Ryan demonstrate the ways this narrative queers heteronormative notions of families and relationships, and contest images of adults and children that are commonly available in young adult and middle grades literature.

Will Banks and Jonathan Alexander explore what it means to create queer characters and identities in their chapter. Banks and Alexander compare more recent titles (Openly Straight by Konigsburg and Two Boys Kissing by Levithan) in YA literature with earlier novels that explored same-sex attraction in YA characters (I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth The Trip by Donovan and The Man Without a Face by Holland) for their portrayal of queer experiences and messages about what it means to be “gay.” They argue that contemporary novels, rather than providing more open-ended options for identities and life trajectories, tend to offer the same options that earlier novels are critiqued for, or even foreclose options more than those earlier novels. By neatly wrapping up the narrative in a “positive” ending with identity resolved, the authors argue that newer, third-wave LGBTQ YA novels limit the exploratory possibilities that earlier texts offered. Banks and Alexander argue against literary homonormativity, in which non-heterosexuality is rendered privatized and depoliticized and becomes normative, because it limits the identity possibilities presented in YA fiction with queer characters, and also limits the options opened to young people to explore through literature. They explore the possibility of reading queerer narratives in the older novels, and suggest that rather than dismissing them as negative and harmful, we can read them in conjunction with more contemporary work for a fuller picture of queer possibilities.

Darla Linville looks at the discursive possibilities offered for girls desiring girls in the narrative of The Difference Between You and Me by Madeleine George. Linville argues that both characters who narrate most of the story, Jesse and Emily, critique dominant images of girls and lesbians, engage in discursive negotiations with the borders of those identities, and claim or reject normative identifications at different times in the story. Linville demonstrates that the character Jesse rejects both heteronormative and homonormative identifications and ideas about community, family, and friendship when she advocates for a politicized and radical community for herself with other likeminded individuals in her school and outside of it, and beyond her age group. She also shows that the narrative offered by Emily resists the label bisexuality but ardently claims the passion she feels for Jesse, and for her more normative image in school. Emily’s complexity offers possibilities for girl identities beyond those often seen in YA fiction. Linville’s analysis offers a new ← XI | XII → reading of this novel, which has been critiqued for missing the queer possibilities by having Emily not come out of the closet.

QUEERING CURRICULUM

The chapters in this section provide examples of how LGBTQ young adult literature can be used in classrooms and professional development to queer the conversation of schools and other educational settings about queer youth. Each of the authors in this section explicitly mentions the ways that LGBTQQ youth are often stigmatized in educational settings, harassed or bullied by peers, and then too often blamed for their victimization by adults who may feel frustrated by the young person who seeks to transgress what are often framed as “appropriate” boundaries. Because discrimination directed at non-heterosexual or gender nonconforming youth may still be widespread, the examples and guidelines offered in these chapters provide an opening for teachers, teacher educators, student services professionals, or school leaders to begin the conversation with peers or with students in their own settings about changing social norms around gender performances and sexual identities.

Jacqueline Bach and Chaunda Allen Mitchell explore the possibilities for complicating student services personnel perceptions of LGBTQ college students through the lens of YA literature. Through a reading group that discussed novels with LGBTQ characters, student services staff were able to examine the many ways college students may be exploring their gender expression or sexual attractions. These storylines offer the opportunity for those who work with students to discuss the complexities of a story without violating a real student’s privacy, and then to apply the discussions to the real lives of students they work with. This chapter introduces a new opportunity to use YA literature that focuses on LGBTQ youth to expand the possibilities for understanding the various ways students may define their sexual and gender identities, and to hear about what they are feeling from inside their heads. In other words, the examples provided in Bach and Allen Mitchell’s chapter show how LGBTQ YA literature may provide an opportunity to queer student services personnel’s beliefs about LGBTQ college students.

sj Miller’s chapter introduces the Queer Literacy Framework and how its tenets can be applied in the secondary English classroom. Miller’s framework contains a list of dispositions that teachers teaching within a queered framework should adhere to, and offers examples of what those dispositions and theoretical assumptions would mean in terms of various presentations of gender, identity, subjectivity, and worldview. Miller asks us to see the injustices in limited presentations of gender roles, presentations, and identities, and to understand how historically those have been limited without a natural imperative or referent. Acknowledging ← XII | XIII → students’ bodied realities, through literature and in classrooms, offers everyone a larger perspective and enables students to feel really included and accepted within the stories that shape their lives.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 227

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433129544

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453917039

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454191261

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454191278

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433129537

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1703-9

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (February)

- Keywords

- sex adult literature LGBTQ Coming-out

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2016. 242 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG