Disrupting Gendered Pedagogies in the Early Childhood Classroom

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

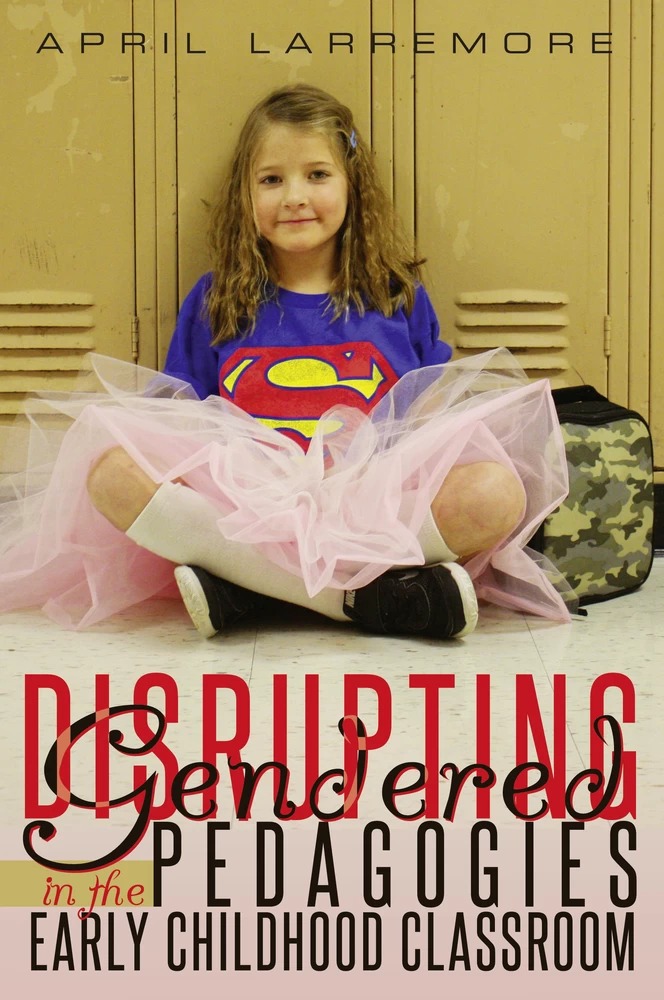

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This ebook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Can I Rethink My Kindergarten Teaching?

- Chapter 2. Critical Autoethnography and Possibilities for Reframing Teaching Practices

- Chapter 3. Disrupting Dominant Constructions

- Chapter 4. Gender and the Schooling of Girls and Boys

- Chapter 5. Shifting Identities, Multiple Subjectivities, and the (Re)Making of a Teacher

- Chapter 6. Creating Liminal Classroom Spaces: Acknowledging My Disruptive Teacher Voice

- Chapter 7. A Letter to Teachers Who Would Be Critical, Disruptive and Transformative

- Chapter 8. Moving Forward in the Journey: Creating a Critically Conscious Classroom

- References

← x | 1 →Chapter 1

Can I Rethink My Kindergarten Teaching?

For many early childhood teachers and professionals, interacting with children about complex and contested issues is fraught with feelings of uneasiness and anxiety. For an unfortunately small number of other teachers, an openness to challenging dominant societal beliefs is considered important if this questioning leads to classroom interactions and pedagogical behaviors that can increase acceptance of diversity with/for children. This book is about one kindergarten teacher’s attempts to reframe classroom power relations—to be willing to challenge the accepted and suitable definition of the “good” teacher—to be willing to be labeled a “bad” teacher if students can benefit from perspectives and interactions that have not been labeled good, developmentally appropriate, or acceptable. I am that kindergarten teacher.

Living with diverse cultures, identities, knowledges, and ways of being in the world, some early childhood educators have called on a variety of approaches and perspectives to meet these positive yet complex challenges of diversity and multiplicity (Grieshaber & Cannella, ← 1 | 2 →2001). The reconceptualization movement in early childhood education has brought about new spaces and lenses through which a different way of thinking about children as subjects has emerged. Looking at early childhood educational practices through diverse feminisms, poststructural, and critical lenses, teachers have, and can, reflexively consider their own positions within discourses and ways that normalizing is unconsciously perpetuated and marginalizes those who are perceived as different.

In our current context, the ways early childhood teachers see, understand, and respond to young children’s work, play, and language are positioned within their knowledge of childhood, teaching, and learning. These knowledges are often monocultural, Universalist, and limiting. In the early childhood classroom, this mindset is oftentimes informed by developmentalism, which in turn is the basis for developmentally appropriate practice (DAP; Bredekamp & Copple, 1997). Developmentalism refers to the overdependence on developmental ways of seeing young children within DAP (MacNaughton, 2000), a knowledge base informed exclusively by developmental psychology that universalizes the child and childhood (Burman, 2008). Concern about this normalizing grand narrative and related other forms of educational marginalization is why I became determined to rethink and reframe my teaching. I chose as my particular focus the narrow developmental interpretation of those who are younger as asexual, ignorant, and innocent. As a teacher, for many years I have perpetuated this view.

Uneasiness and Pressures to Be the Asexual Good Teacher

Despite the intimate links that exist between gender and sexuality, the dominant discourse of childhood has constructed children as innocent, asexual, and too young to understand, thus positioning sexuality as irrelevant to their young lives and yet, at the same time, troublesome for them. For many early childhood teachers and professionals, interacting with children about issues concerning gender and sexuality is fraught with feelings of uneasiness and anxiety. While many early childhood ← 2 | 3 →teachers control expressions of sexuality as if they were biologically determined, researchers who work on sexuality argue that these expressions are more than just sex, but rather they include all of the cultural practices adopted by individuals, in this case young children, such as kissing games, through girlfriend/boyfriend practices, romantic ideals (e.g., pretend families, dating, and marriage rituals), stories, movies, and television shows, as well as daily involvement in sexually based social and legal societal institutions (e.g., marriage). In questioning the belief that children are too young to understand these displays of gender and sexuality, Robinson (2005) has directed our attention to the degree to which these heterosexual assumptions and behaviors are everyday yet unacknowledged routine practices in early childhood settings (Blaise & Taylor, 2012). Young children are gendered through early childhood practices, such as playing mothers and fathers in the dramatic play center, chasing games on the playground, mock weddings, lining children up by gender, and the selection of children’s literature that portrays only the makeup of heterosexual families (Janmohamed, 2010; Robinson, 2005; Skattebol & Ferfolja, 2007). While oftentimes unquestioned or unobservable, sexualities are never completely silenced or removed from early childhood settings (Mellor & Epstein, 2006).

Those who draw upon scientific and Western understandings of child development in order to make sense of young children and their behaviors tend to have concerns about the sexualization of childhood and the loss of innocence. For this reason, most adults either quickly shut down the conversations/behaviors/play or ignore them. Teachers (and parents) often view this silencing as protecting children from hearing or seeing what might be perceived as too sexual in nature and therefore inappropriate. By purposefully disregarding these types of behaviors, children are constructed as asexual. Even in cases where adults consider the play or behavior sexual in nature, they may explain away the child’s actions by saying s/he is too young to really understand what s/he is doing. All of these notions of childhood are founded on the belief that sexuality does not occur until adolescence, a time far removed from a child’s early years (Blaise, 2009). Because of this Western belief in childhood innocence and the fact that adults commonly associate sexuality with sexual intercourse only, very few ← 3 | 4 →studies have been carried out on the sexual knowledge and understanding of young children (Brilleslijper-Kater & Baartman, 2000).

Challenging the revered notion of childhood innocence, there is a body of research (Blaise, 2010) that indicates that young children are enthusiastic to talk about gender and sexuality and do have a considerable amount of knowledge regarding their ability to determine sex differences, name sexual body parts and their functions, and describe what they know about adult heterosexual behaviors. Research has increasingly highlighted how young children themselves are both active and knowing shareholders in seeking and regulating sexual knowledge and engaging in the policing of gender performances of other children and adults, within rigid boundaries of what is widely considered appropriate masculine and feminine behaviors (Alloway, 1995; Davies, 1989. 1993; Grieshaber, 1998; MacNaughton, 2000). Additionally, some research has begun to denote the significant role of the curriculum and educators’ pedagogical practices in constructing and normalizing children’s gendered identities (Robinson, 2005; Robinson & Diaz, 2000, 2006). For example, as part of a participatory action research project, which developed work that supported sexualities equalities in the elementary school classroom, the No Outsiders Project explored ways of addressing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) equalities through the use of storybook readings in English primary schools (Cullen & Sandy, 2009). As part of the study and subsequent to earlier feminist poststructural work (Blaise, 2005; Davies, 1993; Sears, 1999), Cullen and Sandy (2009) proposed that one method to consider was to provide young children with the know-how to deconstruct narratives and subjectivities with their classmates and teachers and to equip them with the ability to question the privileging and silencing of “other” discursive subjectivities. This work suggests that in order to open up identities and render them understandable for young children, we must first voice the unspeakable (Allen, Allen, & Sigler, 1993) by talking openly about sexual and gendered identities in elementary school classrooms. For some in the field of early childhood education, this knowledge has resulted in rethinking their approaches to the gendering of identity in their own classrooms (Hughes & MacNaughton, 2001).

Details

- Pages

- 141

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433133022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453918128

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454199090

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454199106

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433133015

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1812-8

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (April)

- Keywords

- Sexuality Gender Class

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2016. 141 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG