Fragile Memory, Shifting Impunity

Commemoration and Contestation in Post-Dictatorship Argentina and Uruguay

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Contentious Presents, Unsettled Pasts

- Chapter 1: Memory Matters: Towards a Definition of the Commemorative Site

- Chapter 2: A Tale of Two Transitions: Shifting Impunity in the Long Aftermath of State Repression

- Chapter 3: Of Memorials and Victims: Liminal Sites of Homage in Buenos Aires and Montevideo

- Chapter 4: Returning to the Scene of the Crime(s): Transformative Trajectories of Sites of State Terrorism

- Chapter 5: Transitory Transmissions of Memory in Argentina and Uruguay: The Ebbs and Flows of the Escrache and its Recent Iterations

- Conclusion: Fragile Memory, Shifting Impunity: Fissures, Entrepreneurs and Sites in Dialogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series Index

| Figure 1 | Plaza de Acceso [entrance square], Parque de la Memoria, Buenos Aires. |

| Figure 2 | Monumento a las Víctimas del Terrorismo de Estado [Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism], with Río de la Plata in the background, Buenos Aires. |

| Figure 3 | Memorial de los Detenidos Desaparecidos [Memorial to Disappeared Detainees] and Parque Vaz Ferreira, Montevideo. |

| Figure 4 | Close-up of names on the Monumento a las Víctimas del Terrorismo de Estado, Buenos Aires. |

| Figure 5 | Close-up of names on the Memorial de los Detenidos Desaparecidos, Montevideo. |

| Figure 6 | Casino de Oficiales [Officers’ Mess] used as clandestine detention centre, Escuela Mecánica de la Armada [Navy Mechanics School] (ESMA), Buenos Aires. |

| Figure 7 | Pabellón Central [Central Pavillion], ESMA, Buenos Aires. |

| Figure 8 | Entrance to Punta Carretas Shopping Centre, Montevideo. |

| Figure 9 | Information plaque, ESMA, Buenos Aires. |

| Figure 10 | Musicians at the escrache against Oscar Hermelo, Diagonal and Lavalle intersection, Buenos Aires. Photo credit: Alessia Minarelli. |

| Figure 11 | Participants graffiti the ground outside Hermelo’s office with slogans such as ‘Fiscal de la Impunidad’ [Impunity Lawyer], Buenos Aires. Photo credit: Alessia Minarelli. |

All photos belong to the author unless otherwise stated. ← vii | viii →

Fragile Memory, Shifting Impunity would not have seen the light of day were it not for the immeasurable support, dedication and kindness of so many people. The seemingly sage advice of ‘turn your thesis into a book’ does not truly capture the vast amount of work that goes into converting thesis to book manuscript. Although this book has its roots in my Master’s thesis and in my Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded doctoral research (the former completed at the University of London, the latter at the University of Leeds), it has evolved into something quite different. This is, in part, because the objects and contexts under consideration are rapidly shifting, meaning that the book revisits the debates explored in my doctoral thesis, yet explores several new avenues of research.

This study is based on ethnographic research undertaken over a period of years in Buenos Aires and Montevideo, between October 2007 and September 2008, and March 2009 and August 2009. Funding was made possible by a fieldwork grant awarded by the AHRC and from Abbey Santander to carry out fieldwork in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. The Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at University College Cork generously funded my visit to Argentina and Uruguay in August 2013.

Without these periods of fieldwork, this project would lack nuanced insight into post-dictatorship memory. I would like to thank all my interviewees for their openness, advice and willingness to discuss the themes of this work. I have tried as much as possible to faithfully represent the opinions, assertions and claims made by my interviewees. Special thanks should be given to Gonzalo Conte, of Memoria Abierta, for sharing his expertize with me. The staff at the Pro-Monument Commission in Buenos Aires, particularly María Scheiner and Luz Rodríguez, were more than willing to assist on my many visits, as were the guides at the Parque de la Memoria and the ESMA (Escuela Mecánica de la Armada [Navy Mechanics School]). In Montevideo I have been blessed with the help of Magdalena ← ix | x → Broquetas of the Universidad de la República and Laura Bálsamo at the SERPAJ Centro de Documentación. My many interviewees have been a constant reminder of the importance in not forgetting that the issues at stake here are not just the object of academic study. Of the many personal histories and experiences, two stand out: Vera Jarach, whose life has been marked not once but twice by the horrors of state repression and violence, losing her grandfather at Auschwitz and only daughter to the nefarious clutches of the Argentine junta. There is Ernesto Ledjerman, fighting for justice for his parents, who were murdered as they fled Pinochet’s Chile for Argentina. Only recently, he came face to face with one of the men involved in his parents’ murder in a well-publicized television interview. Their tireless activism is not only a source of inspiration, but a timely reminder of the ways in which the past continue to impact the present.

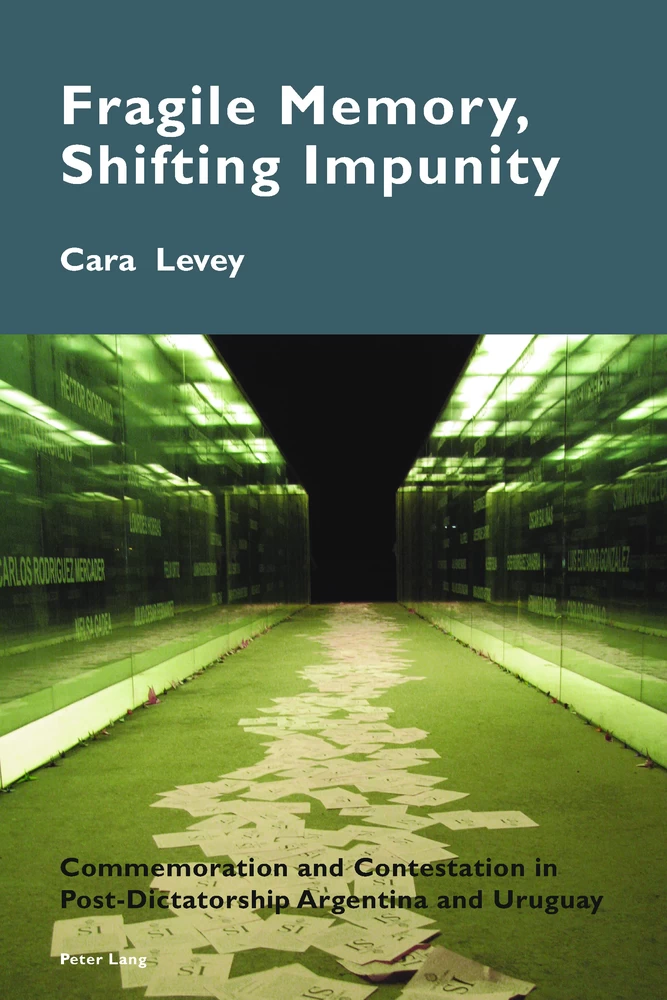

I wish to thank my PhD supervisors: I am grateful to both Ben Bollig for his unwavering support from the moment that I first approached him with the idea for a doctoral project in 2007, and to Paul Garner, who challenged me to think more critically about my work. I must express my gratitude to all the academic and support staff at the Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at the University of Leeds, whose help, as well as friendship, has made the completion of this study not only much a much smoother process, but a more enjoyable one. I am indebted to Brigitte Sion for our many discussions about the Parque de la Memoria [Memory Park] and to Cath Collins for sharing her ideas and encyclopaedic knowledge of Chilean commemorative sites. Laurel Plapp was a fantastic editor. I cannot thank her enough for her support and patience over the last few years. I am grateful to both the Cultural Memories series editor and anonymous reviewers for their insightful and helpful comments, which have permitted the book to realize its potential. Jo Richardson deserves thanks for her careful proofreading of the final draft of this manuscript. Heartfealt thanks go to Cecilia Brum, for providing a cover image that conveys, in so many ways, what the book is about. Thanks also to the many friends I have made through this research, in particular Diana Battaglia, Kristina Pla, Dan Ozarow, Laura Rodríguez and Chris Wylde. Fran Lessa deserves a special mention for her friendship, support and incisive comments on Chapters 2 and 5, and I am indebted to Ale Serpente for our stimulating discussions on postmemory, invaluable to Chapter 5. ← x | xi →

The final part of this book project was completed at University College Cork, my new academic ‘home’ since February 2013. I wish to thank the College of Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Sciences for giving me a Publication Award, and the National University of Ireland for awarding me a Publication Grant. Most invaluable has been the intellectual stimulation and encouragement that I have received since arriving at UCC, particularly from my friends and colleagues in the Department of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies, who have listened and helped find solutions. My heartfelt and sincere thanks also go to Nuala Finnegan and Helena Buffery, whose expertize, guidance and encouragement have profoundly influenced the final stages of this work.

Finally, it is my family to whom I am most indebted. To my husband, Teddy, for his patience and unwavering belief that this manuscript would be completed. To my parents, Ralph and Diane, and my brother Andrew, for the endless post-dinner debates on politics, history and current affairs, fostering a keen sense of curiosity and teaching me far more than I could ever have learnt in a classroom. I was lucky enough to spend a lot of time with my grandparents, in spite of the distance between us. They were all keen storytellers and documenters of the past, be it through family photo albums, or my grandmother’s memories of her childhood as an evacuee in South Africa. The time I spent with them taught me much about the way in which events that are distant in both geography and time can resonate with future generations, sometimes in quite surprising ways. My grandmother, Kit, and my granddad, Norman, were extremely proud to see me complete my PhD, but were not here to see the publication of this book. This book is dedicated to their memory, to that of my grandmother, Rena, and to my granddad, Ivan Levey, the ‘original’ academic in the family. ← xi | xii →

Introduction: Contentious Presents, Unsettled Pasts

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

—William Faulkner1

Years after the end of brutal and repressive civil-military dictatorships in Argentina (1976–83) and Uruguay (1973–85), questions over how state repression should be addressed continue to haunt the urban landscape and trouble public conscience. In late 2009, controversy erupted in Uruguay over the filming of an advertisement for the soft drink Sprite (owned by the Coca Cola Corporation). It was claimed that, during the shoot, the Memorial de los Detenidos Desaparecidos2 [Memorial to Disappeared Detainees], constructed in the late 1990s in homage to Uruguay’s detenidos-desaparecidos [disappeared-detainees], was temporarily covered up by the production company, rendering it camouflaged against Montevideo’s Vaz Ferreira park. Human rights organizations and their supporters denounced the multinational’s use of the site as an attack on the memory of Uruguay’s disappeared and criticized the local government for neglecting the Memorial.3 However, Uruguay was not the only country in which the treatment of dictatorship-era memory caused considerable furore. In early 2013, the Argentine media ran a story on an end-of-year barbecue hosted that previous December by the Justice Minster, Julio Alak, at the most emblematic of the dictatorship-era ← 1 | 2 → clandestine detention centres, the Escuela Mecánica de la Armada [Navy Mechanics School, or ESMA], a designated ‘space for memory’ since 2004.4 Amidst calls for Alak’s resignation and the inevitable public outcry over the appropriateness of holding a barbecue in the place where prisoners’ bodies had been incinerated on pyres, several voices emerged in defence of the celebrations. Among them, Hebe de Bonafini, the well-known leader of one of the two factions of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo [Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo], stated that ‘se puede hacer todo en la ESMA’ [anything can be done in the ESMA], hinting towards the fluidity of the ‘space’ and the multiple and unrestricted uses to which it might be put.5 Indeed, Bonafini, whose two sons and daughter-in-law were disappeared during the dictatorship, has organized cookery classes in the former clandestine detention centre with a view to ‘traer vida a un espacio de muerte’ [bringing life to a space of death].6 Her stance was echoed some months later by Buenos Aires politician, Juan Cabandié, a child of desaparecidos, who welcomed festivities in the ex-ESMA7 and stated that it should be a place for the resignification of the past.8

Although there are glaring differences between the two controversies – in particular, the ESMA’s status as the actual site of human rights violations – both reveal the contestation to which sites of memory are subjected throughout their lifespans, as well as memory’s inherent contentions. They ← 2 | 3 → signal that, rather than draw a line under the past and promote closure of historical interpretation, mobilization around sites of violence or the creation of a memorial precipitates new debates over the past and its interpolation with the present. Such ‘irruptions of memory’ point to the potential and perceived threats facing such sites in terms of their temporary erasure or desecration (demonstrated by the Sprite cover-up) or in debate over a site’s new function (sparked by the ESMA celebrations).9 Meanwhile, these controversies are not exclusive to the post-construction phase of memorials, but are two examples of the many issues that beset commemorative sites from the moment they are first conceived and which reverberate beyond their completion. Whilst the ESMA conversion and construction of the Uruguayan Memorial should be viewed within the broader upsurge in public memory projects in Argentina and Uruguay since the 1990s, the persistence of commemorative debates throughout the long aftermath of dictatorship reveals that although local and national governments have, in recent years, increasingly sanctioned, supported and acknowledged commemorative sites, their precarious future is indicative of the lack of a clear official policy on commemoration. Although both episodes highlight the pivotal role of victims, their families and survivors in territorial disputes over the past as well as in the condemnation of violations more generally, they also indicate the importance of post-dictatorship governments in commemoration. It is this constellation of state and societal actors, and the struggles both within and between them, which comprise the focus of this book, the first to offer a nuanced comparison of the convoluted trajectories of commemorative sites in post-dictatorship Argentina and Uruguay. ← 3 | 4 →

Fragile Memory, Shifting Impunity: Unsettling Sites in Contentious Presents

Adopting an interdisciplinary and actor-centred approach to commemoration shifts focus away from exclusively material or cultural studies readings of marches, memorials and monuments, to explore their emergence and transformation, considering the activism and controversies in relation to broader debates on memory, truth-seeking and justice vis-à-vis the past.Indeed, Fragile Memory, Shifting Impunity constitutes the first book-length study to directly compare types of commemorative sites from Argentina and Uruguay, focusing specifically on the debates, controversies and actors. In recognition of the diversity of groups and individuals who promote, lobby for and mobilize around memory in Argentina and Uruguay, I draw on Elizabeth Jelin’s term ‘entrepreuners of memory’.10 Many of these ‘entrepreneurs’ are those directly affected by state repression: former political prisoners, returned exiles and the relatives of those murdered and disappeared. These so-called afectados, according to Gabriel Gatti, a sociologist working on human rights violations and also a relative of disappeared Uruguayans, illustrate the interface, and indeed blurring of boundaries between, ‘genetic-based’ activism on one hand and ‘affiliation’ on the other.11 However, commemorative processes have more recently involved the active and peripheral participation of a widening circle of actors: members of post-dictatorship generations; those with a limited personal connection to repression; or those enlisted in a professional capacity, like state and societal actors, curators and artists. In this study, the term is also extended beyond those who hope to establish through the sites a lasting link between the past and the present to those who tacitly support commemoration of the recent past and even those who oppose, contest or sabotage particular ← 4 | 5 → commemorative initiatives or attempt to eliminate connections with the past.12 The foregrounding of processes of activism and mobilization and the myriad ways in which state and societal actors contest commemoration, alongside the controversies, obstacles and debates that have emerged between them over the longue durée, permits valuable insight into the construction of memory in all its complexity, an approach that is both timely and necessary, given the political, judicial and societal shifts that have taken place locally, regionally and internationally during the four decades since the end of the dictatorships. Responding to the paucity of research that has attempted such a long view – as discussed in more detail in Chapter 1 – I propose that close analysis of the trajectories of Argentine and Uruguayan commemorative sites is instructive for a study of the factors that influence commemoration, such as past and present national and municipal policies and the strategies of civil society organizations.

In doing so, this study takes the ‘politics of memory’ as a departure point to explore the relationship between memory, the actors involved and the wider debates on justice and impunity. As suggested by Collins, Hite and Joignant, in their important work on post-dictatorship Chile, the ‘politics of memory’ is a relatively new subfield in the global study of memory, as political scientists traditionally steered clear of memory, viewing it as too subjective. When memory was studied by political scientists, it tended to be considered vis-à-vis institutions rather than as an object of study per se.13 However, more recently the political nature of memory has been expanded to include ‘both policies of truth and justice and the way in which a society interprets its past’.14 We should, then, acknowledge memory’s presence in high politics and the judicial sphere, as well as in ← 5 | 6 → extra-institutional and grassroots endeavours to construct memory. This global trend, as Collins, Hite and Joignant’s work on Chile perhaps suggests, has repercussions for Latin America, in which the traumatic past remains part of the lived experience of many citizens and the struggles for accountability are pending. Here, Jelin urges us to conceive the ‘policies of memorialization’ as ‘part of a larger arena of transitional politics’,15 as well as inherently political processes: ‘first, because their installation is almost always the result of political conflicts’ and second, ‘because their existence is a physical reminder of a conflictual past’.16 In this vein, Gatti has argued that memory policies are not only fuelled by the need or desire to fill the void left by the forced disappearance characteristic of the Southern Cone dictatorships, but that these policies are motivated by the search for justice and restitution.17 This aspect is highlighted by the considerable overlap between the actors and groups invested in the struggles for justice on one hand and commemoration on the other. In focusing on the actors and debates, I draw attention to the ‘micropolitics’ of memory, analysing a carefully selected group of commemorative sites within shifting contexts of impunity. Restoring complexity to the politics that underpin commemorative practices in each country reveals a spectrum of conflicts, some that are site- or country-specific and others which speak more broadly to general concerns about memory and justice. Hence, this book’s title – Fragile Memory, Shifting Impunity – denotes its overarching aim: to frame the struggles for memory within shifting contexts of impunity in order to understand the extent to which they constitute a form of non-institutional, reparative or societally undertaken justice (a challenge to impunity through non-judicial means or ← 6 | 7 → alternative ways of ‘doing’ justice), or whether they contribute directly to legal accountability and the post-dictatorship struggles for justice.

Fragile Memory, Shifting Impunity: An Itinerary

Chapter 1 revisits the contentious concept of ‘memory’ in order to set out the original theoretical approach adopted in this study and to establish the term ‘commemorative site’ as a means of analysing the heterogeneous case studies. The starting point is memory’s close relationship to what we know as ‘history’: a reference to the ways in which memory of historical periods or events are manipulated and reworked, as well as the historical development of memories over time. Discussion of memory as a collective phenomenon helps to contextualize the ‘politics of memory’, particularly the fissures generated by commemorative endeavours and the different meanings, stakeholders and visions pertinent to sites of memory. The chapter’s aim is not to offer an exhaustive definition of memory, but to account for the ways in which memory and its (dis)contents are shaped in and by the present, as well as explore the different physical places and symbolic spaces in which proponents of memory intervene. The final part of the chapter moves from the general and theoretical to a comparative and contrastive review of the literature on commemoration and contestation in Argentina and Uruguay, setting out the originality of my approach to this area of study.

Having established that trajectories of memorialization are highly contingent on context-specific distinctions, Chapter 2 sets out the contextual framework, briefly introducing the contrasting experiences of state terrorism in Argentina and Uruguay. The bulk of the chapter is concerned with examining the distinct ways in which state and society addressed crimes committed by past governments in Argentina and Uruguay. In doing so, it distinguishes the fluctuating impunity characteristic of the aftermath of state terrorism, delineating clearly the various overlapping judicial, political and societal shifts that have taken place between the early 1980s and the present. ← 7 | 8 →

Details

- Pages

- XI, 295

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034309875

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035308303

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035394948

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035394955

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0830-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (June)

- Keywords

- Human rights violation Argentina Uruguay Dictatorship State repression

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2016. XI, 295 pp., 11 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG