Poor, but Sexy

Reflections on Berlin Scenes

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

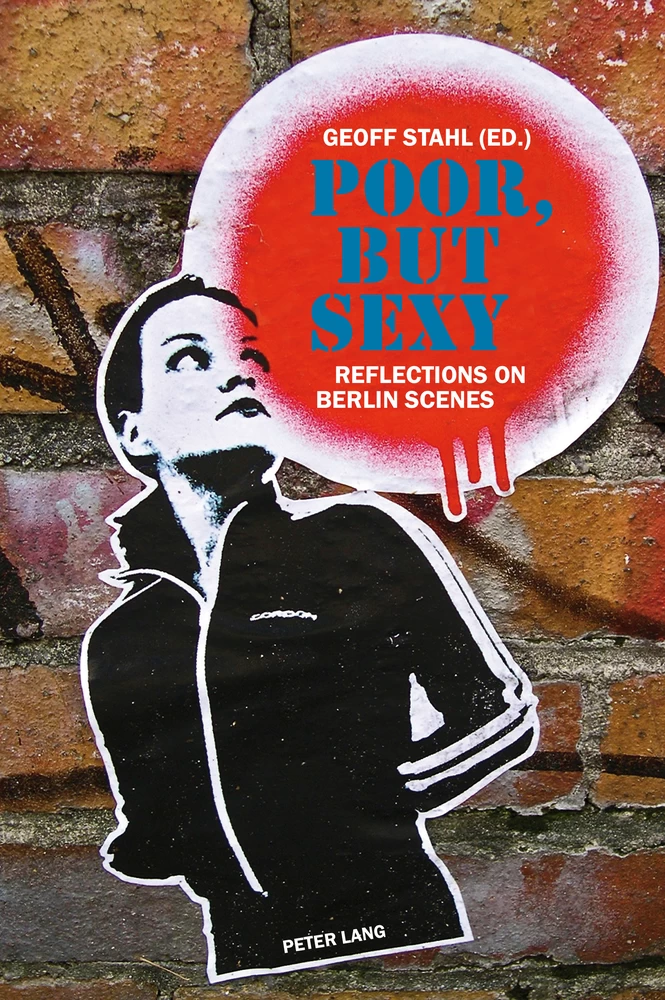

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Editor

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Poor, But Sexy: Reflections on Berlin Scenes

- Introduction

- Works Cited

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Out on the Scene: Queer Migrant Clubbing and Urban Diversity: Kira Kosnick

- In the Mix

- An Eye For It

- Migrant Identities

- Migrant Socialities

- Scenes of Club Culture

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- Russendisko and the German-Russian Folklore Lineage: David-Emil Wickström

- Kasatchok Superstar: The German-Russian Folklore Lineage

- Apparatschik

- Russkaja

- ‘False Russians’: The Stereotyped Strike Back

- The Bigger Picture: Ost Klub and Balkanisierung

- Discography

- Works Cited

- The Reassessment of all Values: The Significance of New Technologies and Virtual/Real Space in the Trans-National German Pop Music Industries: Christoph Jacke and Sandra Passaro

- Introduction: The Current Discussions Concerning Pop Music

- Pop Music’s Dissemination and Marketing Process

- Production: Music Between Niche Product and Mass Product

- Distribution: Are Advertising, Journalism and Public Relations Becoming Superfluous for Pop Music?

- Reception: Land of 1000 Opportunities Versus Lost in Cyberspace

- Processing: From Creativity to the Production of New Products

- Interim Conclusion: Neither the Beginning Nor the End But Right in the Middle

- The Survey of Experts in Berlin

- Approach

- The Respondents

- Interview Results

- Use and Challenges: New Digital Technology and Techniques

- Accomplishments of the World Wide Web

- Individual Use and Media Competence

- Changes on the Social Level

- The Re-evaluation of All Values

- Barriers and Occupational Fields

- Real and Virtual Spaces

- Pop Music: A Cultural Asset

- Forecasts: Prop<yosals for the Future

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- The Scene of Scenes: Berlin Underground Parties, Neither Movement nor Institution: Carlo Nardi

- Introduction

- Methodology

- A Premise

- Underground Parties

- Rhetoric of the Local

- Rhetoric of the Global

- From Employed Work to Self-Entrepreneurship

- Behind the Scene

- Conclusions

- Works Cited

- Berlin Capitalism: The Spirit of Urban Scenes: Anja Schwanhäußer

- Squatting a New Level of Capitalism

- Berlin: A Site for the Fusion of Economy and Subculture

- Kosmonauts of the Underground

- Understanding the Party

- Doing Something

- Enjoying the Moment

- Consuming Drugs

- Holiday Communism

- Example 1: Delinquent fashion

- Example 2: Shopping frenzy

- Example 3: Entrepreneurial Squatters

- The New Capitalism

- Spirit

- Works Cited

- Field Configuring Events: Professional Scene Formation and Spatial Politics in the Design Segment of Berlin: Bastian Lange

- Fuzziness of New Creative Markets

- Field-Configuring Events (FCE): Micropolitics in Space

- Space and Spacing as Analytical Categories: Understanding the Formation of Urban Based Markets and Creative Scenes

- Research Methodology

- Empirical Findings

- The Berlin Case: Launching an Entrepreneurial Project

- Preparing the Place

- Forming Identities: “Universal Dilettanti”

- Playing (with) the Places

- Conclusions: Re-considering Field-Configuring Events (FCE) in Creative Industries

- Field-Configuring Events

- Spaces of Experience: Professional Experiences

- Works Cited

- Berlin’s Underground Filmmakers & Their (Imagined) Scenes, Inside and Beyond the Wall: Ger Zielinski

- Towards Film Scenes

- Berlin Represented as a Cinematic City

- Spaces of Berlin

- Underground Cinemas and Scenes

- Knokke

- Underground Becoming Visible, 1969

- Scene Art

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- Breaching the Divide: Techno City Berlin: Beate Peter

- Works Cited

- Getting By and Growing Older: Club Transmediale and Creative Life in the New Berlin: Geoff Stahl

- Festivals and Cultural Tourism

- The Festive City

- CTM: Origins and Orientations

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- The Unbearable Hipness of Being Light: Welcome to Europe’s New Nightlife Capital: Enis Oktay

- Works Cited:

Poor, But Sexy: Reflections on Berlin Scenes

Introduction

The scene opens up the conversation on the dreamwork of the city, how it arouses dreaming, the desire to be seduced by the present—the dream of the eternal present—in a way that can make it enduring. It is through the idea of the scene what we can begin to recover the notion of the great city as exciting because such an approach leads us to rethink the interior dream of Gesellschaft, the dream that we might be strong enough… to cancel the opposition (between Gemeinschaft-Gesellschaft) and to preserve the difference, that is, to dream the dream of Gesellschaft (that a society can be memorable, that this present can live in time). (Alan Blum, The Imaginative Structure of the City, 2003 176)

In the twenty-plus years since the fall of the Wall, Berlin has undergone an immense transformation on a scale not seen in any other European city. This dramatic urban makeover has been as much cul-tural and social as it has material and symbolic. Alongside the renovation of the city’s built environment, as well as its reputation, a large part of this urban reconstruction has been the foregrounding of the city’s many cultural activities. This has been a process that has reaffirmed and reinvigorated Berlin’s near century-long status as a cultural hub for artists, entrepreneurs and a host of other creatively inclined individuals. This profound overhaul also generated a frenzied entrepreneurial energy, an effervescence made manifest in the many gallery, music, theatre, film, design, new media scenes borne out of the offices, bars, cafés, squats and club cultures of neighbourhoods such as Mitte, Prenzlauer Berg, Kreuzberg, Neuköln, and Friedrichshain. The proliferation and diversity, as well as the success and failure, of these kinds of cultural spaces reaffirms Berlin as a city able to provide a unique urban stage among European cities, its foundations resting on the legacy of a well-established bohemian pedigree that has made possible and, as Rolf Lindner (2006) suggests with regard to cities more generally, makes plausible ← 7 | 8 → its current role as creative city and de facto (sub)cultural capital of Europe. While drawing on its cultural heritage, its attractiveness as a demi-monde is tied also to a sense of creative promise, a complicated appeal that is bound up in a reputation spread through word of mouth, artistic and social networks, urban “boosterism” campaigns, the proliferation of cultural policies, numerous creative funding bodies and academic institutions, urban planning directives, and attractive investment opportunities. The many rhetorical and discursive framings of Berlin as a multi-faceted space of reinvention and possibility situate it as a rich semiotic resource, at one and the same time an iconic city signalling an openness and tolerance to artists, ex-pats and entrepreneurs, as well as an eminently marketable repository of images of a contemporary, up-to-date, and innovative city, neatly tailored to the imperatives of current city-brand managers.

This tension, pitched between those who seek to value Berlin’s cultural spaces as ends in themselves and those that see them as means to other, perhaps more nefarious, purposes (i.e. pecuniary), is a plight shared by many cities. In Berlin, however, the reliance on a fraught promise of good things to come has a particular valence and has taken both an imaginative and material form that has given the city’s contemporary cultural spaces a distinctive character. Janet Ward (2004), for example, has referred to the reimagining of the city over the last fifteen years as helping to constitute what she refers to as the ‘virtual Berlin,’ where the ‘becoming Berlin’ remains only that: a city always imagined, promised, yet forever unrealised. The efforts undertaken to market the city’s thousands of square-metres of office space to investors, on the assurance of good returns and vibrant markets, have for the most part unfolded in vain (minus perhaps the countless hotels and hostels which have sprung up in Prenzlauer Berg and Mitte to cater to an expanding tourist industry). A percentage of these buildings still remain either empty, partially, or only temporarily occupied. While new media start-ups, artists, and a host of entrepreneurs fill many of these spaces, overall the uptake has been slow and not nearly reaching the occupancy rate that their rapid renovating aspired to generate. As Ward suggests, in framing Berlin as a ‘virtual city,’ the symbolic wins out over the material, as the attractiveness of a city’s many cultural spaces remains caught up not in financially lucrative investment appeal, but rather in ← 8 | 9 → what Lindner (2006) has referred to as the dense mesh of textures found in cities. In drawing upon its troubled mythologies, its complex layers of history, and its unstable economic state, it demonstrates the city’s creative resilience as well as highlights the many dilemmas and paradoxes that shape the dream, in Blum’s above sense, of the pursuit of a creative life in Berlin.

Those textures have been brought to life in other ways as well. Ward’s thoughts on post-Wende Berlin also offer a salient counterpoint to the city’s more recent slogan, “Be Berlin,” an attempt to resemanticise Berlin that signals a notable shift in the orientation of the city’s branding strategies. As Ward notes, it has long been argued that Berlin has never fully realised its potential to be a Weltstadt, a “world city.”In the 1910s, to take an early example, Karl Scheffler suggested that Berlin was a city always becoming, never being; or some years later, as Joseph Roth would note in 1930, ‘Berlin is a young and unhappy city-in-waiting’ (1996 125). The various ideologies wrought upon Germany in the ensuing decades brought with it the massive destruction and razing of the city both during and after World War II. This, along with the departure of its manufacturing sector, its primary revenue base, ensured its maturation into a world-class metropolis remained stunted. As Ward, among a number of scholars, notes, the fall of the Wall and reunification of the city did little to improve Berlin’s long-held desire to be a Weltstadt, with chronically high rates of unemployment, the loss of an industrial-based economy, and turbulent in- and out-migration. While the fortunes of some might be changing, particularly those working in the new media and tourism sectors, an invocation and invitation to be Berlin remains haunted by potential rather than realisation, still encumbered by becoming and not yet being.

There is of course more to this phrase ‘Be Berlin.’Launched by the Berlin Senate with much fanfare in 2008, its exhortation is an attempt to eschew this near-century long agony of status-anxiety, to have the city and its citizens resolutely, and finally, “be.”The nature of its address, however, stresses the need for individuals, rather than the city itself, to “be,” and by “be” could mean any number of things. With its clear emphasis on innovation, however, it affixes “being Berlin” to entrepreneurialism, which comes with its own ideological baggage. In a ← 9 | 10 → precarious urban context where responsibility is downloaded onto individuals, and as the German welfare state has withered under austerity measures and economic rationalisation over the last decade, one hears in this insistence the reverberations of neoliberalism, ‘a project of institutional reorganisation, sociospatial transformation and ideological hegemony,’ that has underwritten the erosion of federal and municipal support and diminished once robust cultural subsidies in Berlin (and elsewhere) (Brenner, Peck and Theodore, 2012 13). In this context, if, as Roland Barthes (1986) reminds us, the city is a discourse, this new slogan ‘Be Berlin,’ typically represented as set within a distinctive red speech balloon, works to speak for and through its intended addressees, and thus interpellate and produce an unsettled and restless urban subjectivity as well as an ambiguous civic identity, or, in linguistic terms, a more troubling individualised, atomised parole to the city’s collective langue.

Barthes (1972) has also reminded us that ‘myth is a type of speech’ and in “Be Berlin” there is an ideological and ontological sleight of hand at work. There is an expectation to inhabit Berlin such that the addressee take on the habitus of the city, commit to being a Berliner, whatever that may mean, but to also serve at the same time as an ambassador for the city. As the campaign patter suggests (disavowing the city’s previous incarnation as Schaustelle, or Showcase, Berlin which made a spectacle of its massive renovation. See Ward, 2004; 2011, for more on this), Berlin is not about large-scale events, but about things happening at the level of the innovating individual. The suggestion then is that people will find a way to make their life in Berlin “eventful,” the city again a site of possibility, a locus for reconstructing one’s self and actualising creative potential. More importantly, the labour of selling Berlin, of being branded a Berliner and bearing the brand of Berlin, of taking on the onus of promoting and celebrating its civic assets, is now expected to be both the burden as well as hallmark of a good citizen.

This entreaty to ‘Be Berlin’ also fits into agendas tied to the city being cast now as a model “creative city,” with its many scenes being continually celebrated as part of the urban package. The creative city, a term also emptied out of meaning at the exact moment of its ubiquity as cultural policy buzzword, has been made synonymous with Berlin. An assortment of the issues related to the creative city play themselves ← 10 | 11 → out in many of its scenes. In this sense, this volume’s titular term “scenes” is one that presently enjoys currency among city marketers and brand managers, as well as sociologists, urban anthropologists, and popular music as well as media studies scholars. As Will Straw (1991) has described it, and as it is being used by many of the contributors in this collection, a scene is a cultural space within which sit a number of institutions, ranging from bars, cafés, universities, and clubs, which in concert facilitate the generative intersection of a number of social and cultural phenomena, from film, to theatre, to music-making where a fecund assortment of activities serve to inform, influence and help cultivate one another. Alan Blum (2003) has contributed to this notion of the scene as a distinctive urban social form, noting its status as an ‘occasion,’ a privileged time and place whereby a form of collective life unfolds that ties itself to the city by being in the moment, ever present, up-to-date. Blum suggests that in the city can be found a variety of scenes, from gay to bar to restaurant scenes, each of which provide a context where a certain life of quality of life and life of quality are cultivated. He describes these scenes as examples of being private in public, their appeal underpinned by a feeling of shared intimacy. Along these lines, scenes demonstrate the value of collective life in the city in part because they serve as incubators and insulators from which an alluring social power emanates (Stahl 2004).

This social power is more deeply rooted in what Richard Sennett (2008) has argued are the two essential virtues that cities provide: subjectivity and sociability. In the city, the ability to define one’s own needs, through differentiation and distinction, the existential thrill of finding one’s sense of self (to experience the diversity of the city in order ‘to live with multiplicity within themselves’) is married to the elective affinities confirmed through a coming together with like-minded others, affirming the social power of collective life (109). Scenes exist as crucibles where both these virtues can nourish one another in highly intense and mutually reinforcing ways, and it is this energy that pulses through a city’s cultural spaces, and serves as a catalyst for yet more creative activity, but also, when tamed, can signal or anticipate a scene’s eventual decline. They are times and places where, as Blum reminds us, art and the commodity are held together in productive tension. On this point, and because they matter to the social, cultural ← 11 | 12 → and economic life of any city, the wax and wane of these kinds of social energies generated by the city’s various scenes are invariably used as a measure of its cultural vitality, as indices, which, in a globalised cultural economy, are important “quality” attractors for artists, knowledge workers and investors. In post-industrial cities, such as Berlin, this is a dominant organisational logic for brand marketing. You can see it, for example, and again contrary to how the ‘Be Berlin’ campaign imagines it, in the way large scale events such as festivals have become an important part of the culturalisation of the city, where entire infrastructures are assembled, promotional campaigns launched, and tourist packages put up for offer. From the film-based Berlinale to the fashion-fête Bread and Butter, festivals have become ways of harnessing and capitalising on the energies and expertise that nourish, and are nourished by, scenes. You can discover it also in the club culture in Berlin where there exists a particularly salient example of the experience economy, and the attendant tourist industry, that post-Wende Berlin increasingly relies on. Tobias Rapp (2010), for example, has written of the ‘Easyjet Set,’ groups of tourists, coming primarily from the UK, who fly in to Berlin for a weekend of partying at clubs such as Berghain and Panorama Bar, or come for a fashion week such as Bread and Butter. Berlin incarnated in this way is packaged as a phantasmagoric site of cultural consumption embedded in a European as well as global tourism industry. In its club culture and its myriad festivals, the social, cultural, material and symbolic dimensions of Berlin are charged with an intensity, ‘buzz’ in marketers’ as well as Richard Florida’s (2005) term, that inflect one another, coalescing to form a city-as-sign and city-as-scene, which puts culture, often problematically, at the fore of Berlin’s contemporary urban identity.

This troubling notion of ‘urban buzz’ and its bearing on the social and cultural production of urban space can be yoked together with the connotative power of “being Berlin”, and the title of this collection, Berlin as ‘poor, but sexy,’ in order to bring in to focus the scaffolding upon which the chapters that follow can better be set. Alan Blum’s (2010) commentary on Richard Florida and the latter’s celebration of the “creative city” makes apparent how these three points can be put ← 12 | 13 → into fruitful relation to one another, pointing to the Gestalt of this collection, particularly around the links between scenes, creativity and the “creative city”:

The platitude of creative city (and person) is a formula made accessible to any generation for thinking of its life at present as consequential and of one’s self as “interesting” and free from being marked by the past in ways that might hinder its self expression as such. Thus, a platitude such as “creativity,” when applied to persons or collectives, is a formula for self identification and for describing one self as special, a strategy of self enhancement that Florida discovers people and collectives to require, a gesture reminiscent of the “power of positive thinking.”In giving a positive feeling to all, the formula is a way of doing assurance by diagnosing a population in a manner designed to encourage good feelings about one self.(Blum 2010 76)

Here, suggests Blum, the creative city is framed by Florida as a vehicle for personalised actualisation, with Sennett’s urban virtues now cast as one-dimensional aids to self-improvement. More importantly, Blum’s critique of Florida’s banalisation and simplification of the city as locus for creativity usefully moves us away from the salubrious potential implied in “Be Berlin,” and instead helps in recalling that earlier cheekier, and ambivalent, platitude of Berlin as ‘poor, but sexy’ (‘arm, aber sexy’).

First uttered by Berlin’s mayor, Klaus Wowereit, almost ten years ago, this refrain, ‘poor, but sexy,’ had once cast Berlin as the cool, subcultural capital of Germany and Europe. Today, however, it is reduced to a faint-praise brand, stretched to the breaking point over thousands of handbags, its meaning thinned out across t-shirts, postcards, documentaries, songs and websites. It follows that its usefulness as a Berlin motto is nearly exhausted. This could, in one way, be put down to simple demography. The cachet associated with eking out a subsistence existence, even if done stylishly, seems less romantic these days, certainly among members of an ageing creative labour force, Florida’s “creative class,” who are also now seeking sustainable means to support new families, their creative energies channelled into another kind of fecundity found in child-centric neighbourhoods such as Mitte and Prenzlauer Berg (Buck 2008). Given these social facts and fates, and the ensuing decade’s changing economic imperatives, the slogan’s ← 13 | 14 → cheekiness has lost its descriptive purchase. In response, Wowereit has since modified his declaration, minus some of its poetry: ‘We want Berlin to become richer and still remain sexy’ (FAZ 2011). Even he recognises it comes across a bit tattered nowadays, a tacit acknowledgment of its (and his) guilt as an accomplice in giving a more instrumentalised shape to cultural life in the New Berlin. Its ability to capture the subcultural character and street-wise sensibility of Berlin looks to be waning in the face of marketing and branding forces assembled to mine, and thus better realise as well further ironise, the semiotic richness of the phrase’s self-deprecation, a point made even more acute when it is pitted against the euphoric, upbeat incitement to “Be Berlin.”

Details

- Pages

- 225

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034313391

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035106237

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035199000

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035199017

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0351-0623-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (June)

- Keywords

- queer filmmaking techno scene club culture

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 225 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG