Santiago de Compostela

Pilgerarchitektur und bildliche Repräsentation in neuer Perspektive

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Titel

- Copyright

- Zitierfähigkeit des eBooks

- Über das Buch

- Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Vorwort

- Santiago und die Pilgerstraßen – Die schriftlichen und baulichen Zeugnisse im neuen Fokus / Santiago y los caminos de peregrinación – Construcciones y testimonios escritos desde una nueva perspectiva

- Imagines Cathedralis Ecclesiae Compostellanae: The Mediaeval Basilica in the Drawing of the Obradoiro Square by the Canon José de Vega y Verdugo (1657)

- De qualitate aecclesiae: Architectural Description in the Pilgrim’s Guide to Santiago de Compostela

- Die Capella episcopalis – Überlegungen zur topographischen Lage der Privatkapelle von Erzbischof Gelmírez

- Frenesí jacobeo y restauración monumental La catedral de Santiago de Compostela a mediados del siglo XX

- Die Kathedrale von Santiago in neuer Perspektive / La catedral de Santiago desde una nueva perspectiva

- The Mysteries of Santiago

- New Perspectives on the Romanesque Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

- Neue Forschungen zur Baugeschichte der Kathedrale von Santiago de Compostela – bauliche Entwicklung und Bauphasen des Langhauses

- Die Kapitelle im Langhaus der Kathedrale von Santiago de Compostela

- Die Choranlage unter Peláez und Gelmírez – Bau- und Planungsabschnitte

- New Thoughts on the West Crypt of Santiago de Compostela

- Der Westbau von Santiago de Compostela

- The Populated Porch: Figures and Foliage in Spanish Sculpture before the Pórtico de la Gloria

- From Transfiguration to Parousia Examining the Development of the West Portal of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

- Zu Mateo und seiner Inschrift am Pórtico de la Gloria

- Laster, Feindbild und der polylobe Bogen: Die Kathedrale von Santiago de Compostela und der Islam

- Trascoro oder Hallenlettner? – Zum mittelalterlichen Lettner der Kathedrale von Santiago de Compostela

- Santiagos Stellung innerhalb der Romanik Spaniens und Frankreichs / Santiago en el contexto del arte y de la arquitectura románica de España y Francia

- La escultura de San Isidoro de León y su relación con otros talleres del Camino

- Der Pórtico de la Gloria im Beziehungsgeflecht der nordspanischen Skulptur

- L’architecture de Saint-Sernin de Toulouse et ses liens avec Saint-Jacques de Compostelle

- Cluny und Santiago

- Grabkult der Heiligen und apostolische Konkurrenz Pilgerkirchen im aquitanischen Kulturraum als Modelle für Santiago de Compostela

- Saint-Trophime in Arles und Saint-Gilles-du-Gard Neuere und aktuelle archäologische Forschungen zu den romanischen Kirchenbauten und ihren Skulpturenfassaden an der provençalischen Via Egidiana

- Santiago – Rome – Jerusalem: Old Issues, New Proposals

- Das Prinzip der Junktion Antike Zeitzeugenschaft vom Fernando-Kreuz bis zum Pórtico de la Gloria

- Autorenverzeichnis

- Bildnachweise

Abb. II: Santiago de Compostela, Kathedrale, Pórtico de la Gloria, Tympanon, Evangelist Markus.

Abb. II: Santiago de Compostela, Kathedrale, Pórtico de la Gloria, Tympanon, Evangelist Markus.

← 8 | 9 →

Seit Antonio López Ferreiros epochalem Werk zur Geschichte der Kathedrale von Santiago de Compostela vor mehr als einem Jahrhundert hat die Erforschung dieses einzigartigen Bauwerks, seiner künstlerischen Ausstattung und seiner historischen Bedeutung zu Beginn des 21. Jahrhunderts einen neuen Höhepunkt erreicht. Nicht nur als zunehmend frequentiertes Pilgerzentrum, auch als Objekt der kunsthistorischen, baugeschichtlichen und historischen Forschung ist die Kathedrale mit ihren Annexbauten als Höhepunkt der Kunst und Kultur am Pilgerweg wieder in aller Munde. Treibende Kraft dieses neuerlichen wissenschaftlichen Interesses an Santiago und seiner Kathedrale ist die gleich auf mehreren Ebenen manifeste Erkenntnis, dass mit den herausragenden Arbeiten von López Ferreiro zur Geschichte und der grundlegenden Dissertation von Kenneth John Conant, 1926, zum Bauwerk eben nicht alles gesagt ist. Viele Fragen bleiben vielmehr bis heute offen bzw. werden kontrovers diskutiert, wobei die unterschiedlichen Gattungen, insbesondere die Skulptur, meist in separaten Untersuchungen, meist weitgehend losgelöst vom Bauwerk selbst und den Bedingungen eines komplexen Bauablaufs, abgehandelt werden.

Für die Herausgeber dieses Kolloquiumsbandes und ihr Team aus Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftlern sowie Studierenden der Universitäten in Bern und Cottbus sowie der Hochschule RheinMain in Wiesbaden führte dies zu zahlreichen langen Tagen, mehr noch zu langen Nächten in der Kathedrale mit dem durchaus schwer erreichbaren Ziel, Neues zum umfangreichen Forschungsstand beizutragen und die Diskussionen um alte, gleichwohl aber brennend aktuelle Forschungsfragen durch neue Beobachtungen und Perspektiven zu bereichern. Diese neuerlichen Forschungen stellen den Baubefund selbst in den Mittelpunkt und erschließen das Bauwerk als Quelle für die Erarbeitung einer architekturbasierten Baugeschichte, die eng mit der geisteswissenschaftlichen Kunstgeschichte zusammenarbeitet. Hierbei mussten beide Seiten von liebgewonnenen Vorstellungen und in Handbüchern etablierten Bildern Abschied nehmen. Bei dieser Art der Forschung geht es weniger um richtig oder falsch, sondern um einen fortlaufenden Erkenntnisprozess, der tatsächlich ergebnisoffen ist und dessen Resultat sich erst nach und nach aus einer Fülle von Einzelbeobachtungen ergibt.

Die Santiago-Forschung stellt ein besonderes Kapitel der Wissenschaftsgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts mit dezidiert artikulierten Meinungen dar – man denke nur an Kingsley Porters Schlachtruf „Spain or Toulouse“ und seinen transnationalen Ansatz, das Netzwerk der Pilgerstraßen für die Betrachtung von Architektur fruchtbar zu machen, oder die Diskussion um die Zuschreibung des Westbaus der Kathedrale an Meister Mateo und seine Werkstatt durch den jüngst verstorbenen Serafín Alvarez Moralejo, der den Forschungen zu Santiago seit den 1970er Jahren so wichtige Anstöße geben konnte, und an die Arbeiten Michael Wards, die aus der Sicht einzelner Disziplinen zu teilweise unvereinbaren, aber umso forcierter vorgetragenen Interpretationen des Bauablaufs führten.

Demgegenüber ist es heute die Vielfalt der Methoden, verbunden mit Ergebnisoffenheit und einer konzertierten Bau- und Quellenerfassung, die eine Interpretation der komplexen Befunde aus der Sicht aller beteiligten Disziplinen erst kohärent möglich macht. Dass diese Arbeit, trotz aller Anstrengungen, mit Lust, Freude und nicht wenigen Erfolgserlebnissen verbunden ist, verdanken wir der offenen und freundschaftlichen Atmosphäre innerhalb unserer Teams und der äußerst fruchtbaren Zusammenarbeit mit den Kollegen der wissenschaftlichen Einrichtungen vor Ort. Hierfür danken wir allen Beteiligten, Unterstützern und Freunden des Projektes von Herzen.

Mit der Berner Tagung im März 2010, deren Ergebnisse hier vorgestellt werden, wurden zwei Ziele verfolgt: wir wollten unsere seit 2004 durchgeführten Forschungen vorstellen, ihre Ergebnisse mit den international renommierten Fachleuten der Santiago-Forschung diskutieren sowie gleichzeitig den Forschungs ← 9 | 10 → stand im internationalen Maßstab reflektieren und durch fruchtbare Diskussionen bereichern. Unsere Forschungen zum Bauablauf, zur Baugeschichte und Bauplastik sowie den historischen Quellen in Santiago wären nicht möglich gewesen ohne die großzügige Unterstützung der Gerda Henkel Stiftung, der Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, des Schweizerischen Nationalfonds (SNF) sowie die andauernde großzügige Förderung durch Herrn Alfred W. Doderer-Winkler. Ihnen sei an dieser Stelle im Namen aller Projektbeteiligten herzlich gedankt.

Zu danken ist auch dem Kathedralkapitel von Santiago de Compostela, insbesondere seinem emeritierten Dekan Don José María Díaz Fernández, der unsere Arbeiten in der Kathedrale und auch die Vorbereitungen zur Berner Tagung großzügig und mit außerordentlichem Interesse unterstützt und auch den Weg nach Bern nicht gescheut hat, um an der Tagung teilzunehmen. Ihm und dem Museo de la Catedral de Santiago de Compostela, seinen damaligen Direktoren Don Salvador Domato Búa und Don Alejandro Barral Iglesias sowie dem Director Técnico Ramón Yzquierdo Peiró, der Comisión de Cultura y Arte und der Fundación Catedral de Santiago mit ihrem Präsidenten, Don Daniel C. Lorenzo Santos, dem jetzigen Dekan, Don Segundo Pérez López, dem Erzbistum sowie allen übrigen kirchlichen Stellen in Santiago gebührt besonderer Dank für die fruchtbare Kooperation, die große Unterstützung unserer Arbeiten und den organisatorischen Aufwand, der nicht selten nötig war, um die Bedürfnisse der Wissenschaft mit denen des täglichen Betriebs der Kathedrale zu koordinieren.

Die Erforschung großer, komplexer Bauwerke, wie der Kathedrale von Compostela mit ihren reichen Ausstattungsstücken und umfangreichen schriftlichen Quellen ist heute, dies zeigt die über hundertjährige Forschungsgeschichte, von einem einzelnen Forscher nicht mehr zu leisten – viel zu komplex sind die technischen Anforderungen und viel zu umfangreich die Quellen und Vergleichsobjekte. Die Kathedrale von Santiago ist zudem ein besonderes Beispiel für ein breites internationales Forschungsinteresse – renommierte Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftler aus Spanien, Amerika, Deutschland, England, Frankreich und der Schweiz arbeiten derzeit an unterschiedlichen Fragen rund um das Bauwerk, seine Geschichte und die Vergleichsbauten, insbesondere in Frankreich. Ihnen allen sind wir sehr dankbar, dass sie unserer Einladung nach Bern gefolgt sind und nun auch wesentlich zur Publikation der Tagung beitragen. Die Erforschung eines so umfangreichen Objektes ist ohne die breite Unterstützung und Diskussion durch internationale Fachleute nicht möglich. Und wir hoffen, dass die Berner Tagung und ihre Publikation Anfang und Anregung bieten für neue interdisziplinäre Forschungsprojekte und -kooperationen im Kontext der Architektur des Pilgerwegs. Eine geeignete Plattform wurde in den letzten Jahren mit den Lecciones Jacobeas Internacionales der Unversidade de Santiago de Compostela mit ihrem Co-Direktor Miguel Taín Guzman eingerichtet, dem wir für seine stete Unterstützung vor Ort sehr danken möchten.

Das vorliegende, umfangreiche Buch spiegelt mit seinen drei Teilbereichen das volle Programm der Tagung wider: Einmal Santiagos Stellung innerhalb der Pilgerstraßen, basierend auf den mittelalterlichen Quellen und den liturgischen Praktiken, zweitens zum Bauwerk selbst und seiner künstlerischen Ausstattung mit Ansätzen einer Neuinterpretation der Bau- und Ausstattungsgeschichte sowie schließlich Santiagos Stellung innerhalb des künstlerischen Austausches mit Nordspanien, Frankreich und Italien.

Neueste Forschungsergebnisse und etablierte Forschungsmeinungen trafen schon während der Tagung aufeinander und charakterisieren auch die vorliegende Publikation. Naturgemäß bleiben die vielen neuen Entdeckungen und Einzelbeobachtungen am Bauwerk nicht ohne Kommentar und ihre Interpretationen, die teilweise etablierten Forschungsmeinungen widersprechen, wurden kontrovers diskutiert. So ist es auch aus der Anlage der Tagung heraus durchaus beabsichtigt, dass unterschiedliche Wertungen in der vorliegenden Publikation nebeneinander stehen. Die Widersprüche zeigen eindrücklich, dass mit dieser Tagung ebensowenig ein Ende der Forschung in Sicht, noch ein allgemein verbindlicher Erkenntnisstand erreicht ist. Die Beiträge sind vielmehr als neuer Anfang zu verstehen und versammeln Aspekte, die die Perspektive auf das Bauwerk und seine Geschichte verändern und im Idealfall neue Wege der Forschung aufzeigen. Als gemeinschaftliche Forschergruppen der Universitäten Bern und Cottbus haben wir ← 10 | 11 → versucht, unsere derzeitigen Erkenntnisse soweit wie möglich kohärent darzustellen und so eine Zwischenbilanz unserer langjährigen Forschungen vorzulegen.

Viele haben zum Erfolg der Tagung in Bern und zum Erscheinen der vorliegenden Publikation beigetragen. Katrin Kaufmann, Sarah Keller und weitere Studierende, insbesondere Laura Hindelang und Jasmin Riedener sowie Wissenschaftler und Mitarbeiterinnen des Sekretariats des Instituts für Kunstgeschichte der Universität Bern haben sich für die perfekte Organisation der Tagung und die Publikation eingesetzt. Anke Wunderwald, Annette Münchmeyer, Roland Wieczorek, Rex Haberland und die Studierenden Josefine Kaiser, Sina Akik, Manuela Fritzsche und Christopher Jarchow aus Cottbus haben für die schöne Begleitausstellung mit neuen Bauaufnahmen und Fotografien der Kathedrale gesorgt, die zum großen Teil in den entsprechenden Beiträgen dieser Publikation wiederzufinden sind. Anke Wunderwald und Judit Vega Avelaira haben mit ihren dichten Kontakten nach Spanien und ihren immer wieder bereichernden inhaltlichen Anmerkungen erheblich zum Erfolg der Tagung und zur Entstehung der Publikation beigetragen. Ihnen allen sei an dieser Stelle herzlich für ihren Einsatz und ihre konstruktive Mitarbeit gedankt. Wir danken darüber hinaus ganz besonders dem SNF und der Hochschulstiftung der Burgergemeinde Bern für ihre großzügige Unterstützung, dem Beer-Brawand Fonds, der Ellen J. Beer Stiftung und dem Hüttinger-Hahnloser-Fonds. Die Publikation und ihre Vorbereitung wurde großzügig vom SNF finanziert.

Die nun vorliegende Publikation der Tagung wird nicht nur von den beteiligten Autorinnen und Autoren mit Spannung und Ungeduld erwartet. Sie hat sich aus den verschiedensten Gründen verzögert, wofür allein die Herausgeber verantwortlich sind. Wir hoffen dennoch, dass die zahlreichen und umfangreichen Beiträge in diesem Buch dazu beitragen, die wissenschaftliche Diskussion um die herausragende Stellung der Kathedrale von Santiago de Compostela in der Kunst- und Baugeschichte neu zu entfachen und zu bereichern, und dass sie zu neuen Forschungen an diesem faszinierenden Ort Anlass geben. ← 11 | 12 →

Santiago und die Pilgerstraßen – Die schriftlichen und baulichen Zeugnisse im neuen Fokus

← 12 | 13 → ← 13 | 14 →

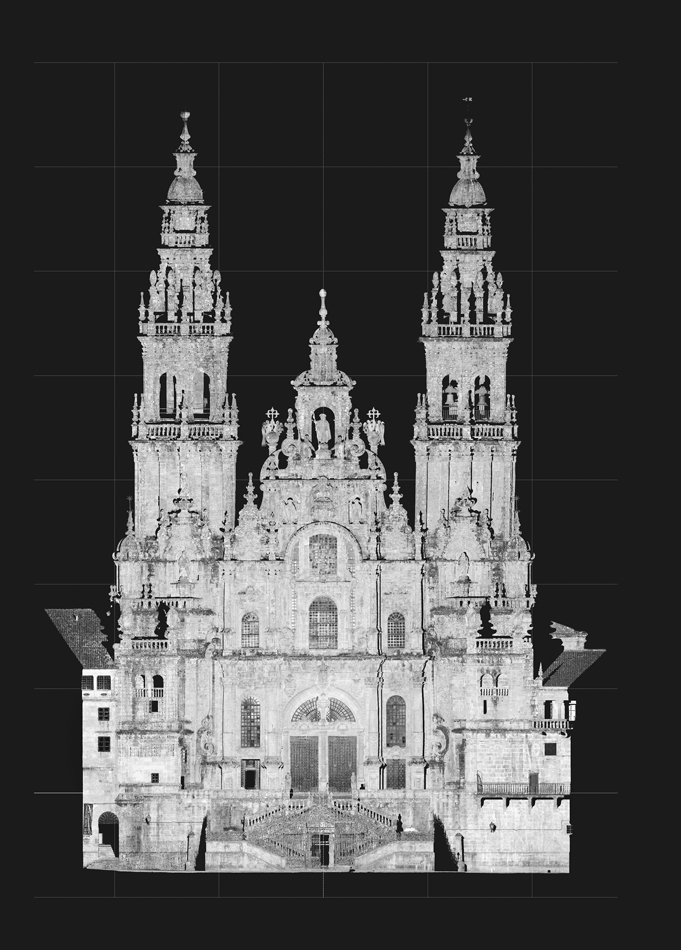

Abb. IV: Santiago de Compostela, Westfassade, Gesamtansicht, Laserscan.

Abb. IV: Santiago de Compostela, Westfassade, Gesamtansicht, Laserscan.

← 14 | 15 →

Imagines Cathedralis Ecclesiae Compostellanae:

The Archive of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela includes an exceptional manuscript in relation to the history of the building, entitled Memoria sobre obras en la Catedral de Santiago (Report of Works in the Cathedral of Santiago) written between 1656 and 1657 by the then young canon Jóse de Vega y Verdugo.1 This report was addressed to the cathedral’s Chapter with his ideas for the renovation of the old Basilica of the Apostle, and is a fundamental work of seventeenth-century Spanish artistic literature,2 classified by the historian Sánchez Cantón as one of “the few theoretical Spanish testimonies that refers to the Baroque style”.3 Its origin is explained by the Counter-Reformation and the desire to renew Spain’s cathedrals, in order to acclaim the Eucharistic cult, the image of the saint in the temple and the relics.4 Effectively, in the folios of the manuscript the canon proposes renewing the mediaeval elements in the main chapel (the altar table, the front panel and altarpiece made on the orders of Archbishop Gelmírez; the image of St. James from the thirteenth century, and the baldachin of Archbishop Fonseca); modifying the monstrance of Antonio de Arfe; and re-opening the legendary crypt containing the Apostle’s tomb, a proposal that led to the first exploration of the Roman mausoleum some years later.5 The last few pages contain two sections dedicated to explaining his ideas for altering certain features on the façade facing on to the Obradoiro Square (entitled “Espexo y torres”, folios 39v.–45v.) and the Quintana Square (entitled “Quintana”, folios 46r.–48r.). In the first, he supports carrying out work on the towers and their roofs, adding a new structure for the bells on the South Tower, building the North Tower at the same level as the South Tower, and covering both structures and the central rose window with three slate spires in the same style as those used in the monastery of El Escorial. However, for the Quintana square he proposed constructing a new façade from the Clock Tower to the Holy Door, in order to conceal the Quintana entrance to the south transept and the mediaeval chevet with its ambulatory and numerous chapels, from the view of local inhabitants and pilgrims.

The Memoria is composed of fifty-one folios6 measuring 310 × 218 mm, consisting of bifolios or several loose folios stitched together,7 written ← 15 | 16 → and illustrated by Vega y Verdugo himself.8 Structurally it is a unitary manuscript, with the same type of paper, watermark9 and sepia ink, with the exception of two folios with the text written in black ink that were added subsequently using tabs, of the two drawings of the baldachin and of the three exterior views of the cathedral.10 It conserves the original folio numbering up to page 48, although it is partially crossed out and/or modified from folio 35 onwards.11 In the text it is possible to distinguish that it was written in two separate stages, separated by a few days or weeks, or at most a few months. One part reaches as far as folio 39r., with the canon’s project to renew the main chapel, with the second part beginning on folio 39v up to folio 48, with his proposals to reform the façades and their corresponding plans.12 This extension can be seen in the index, as by including more text, the author was obliged to extend it, adding folio 5, written in black ink, with the titles of the new sections. It should be remembered that the index is the last part to be written in any type of work, and once it is considered to be complete, then numbering the whole manuscript correlatively until reaching the end, in this case folio 48.13

What makes the manuscript truly exceptional is that it is illustrated with twelve magnificent drawings of the cathedral, its furnishings and religious items from its main chapel, as well as plans with new proposals: these are the drawing of the sacrarium of the monstrance of Antonio de Arfe which was intended to be removed (fol. 23a), his project for the urn of the Monument for Holy Thursday (fol. 23b), the monstrance of Arfe with the new pedestal (fol. 24r.), the Romanesque altarpiece of Archbishop Gelmírez (fol. 27r.), the appearance of the tabula inserted in a chest in the time of Vega y Verdugo (fol. 29r.), his designs for the construction of a new cenotaph for the apostle’s remains (fol. 31r.), his first design for the baldachin (fol. 36), his second design for the baldachin (loose drawing), the appearance of the façade in the Obradoiro Square at the time (loose drawing), his project for its reformation (loose drawing), a diagram showing how to install the slate on the spires he proposed building in the Obradoiro (fol. 40v.) and finally, the appearance of the façade in the Quintana Square at the time of writing the text (loose drawing). Unfortunately, the last four designs are currently split off from the original manuscript. They are four bifolios of different sizes, which are kept loose in the Collection of Maps, Plans and Drawings of the Archive.

The chronology of the Memoria is immediately prior to the appointment of Vega y Verdugo ← 16 | 17 → as the churchwarden (fabriquero), a post he held from 1 May 1658,14 which allowed him to put into practice many of the ideas it contains. However, as previously mentioned, it can be seen that the text was written at two different times, although separated by a short period. The first part, dedicated to the renovation of the main chapel, dates from between 26 May 1656, the date when several silver candlesticks made by Andrés de Campos Guevara were delivered, which are criticised in the manuscript,15 and an uncertain date from the same year prior to the arrival in the cathedral of a design from Madrid for a new monstrance,16 a fact which the author does not mention in the chapters dedicated to this piece of furniture, despite its importance, as it had still not occurred. In the case of the chronology of the second part, dedicated to the drawings of the façades that interest us here, I coincide with García Iglesias17 in associating it with the chapter act of 8 June 1657, when the chapter decides to construct the first Pórtico Real of the Quintana Square, with the “assistance” of Vega y Verdugo, “for having offered himself for this purpose”.18 The declaration of the introduction to this appendix, where the author affirms that:

Although I only had the intention of writing the work of the main chapel of the Holy Apostle, on seeing the main door of the Church that is in need of precise adornment, and furthermore the façade on the Quintana that faces towards San Payo, I have not wished to do so, if at any moment this is a question of importance, I have put down my opinion in writing,19

when no reference had been made in the previous chapters to the outside of the cathedral, indicates that it was written at a later date, and probably connected to the assistance being offered. Also, this statement shows that it was written in relation to the concerns that arose regarding the condition of the main chapel, forming a unitary, finished programme for the renovation of the cathedral building as a result of concerns voiced by the chapter at two specific moments in time that were very close together.

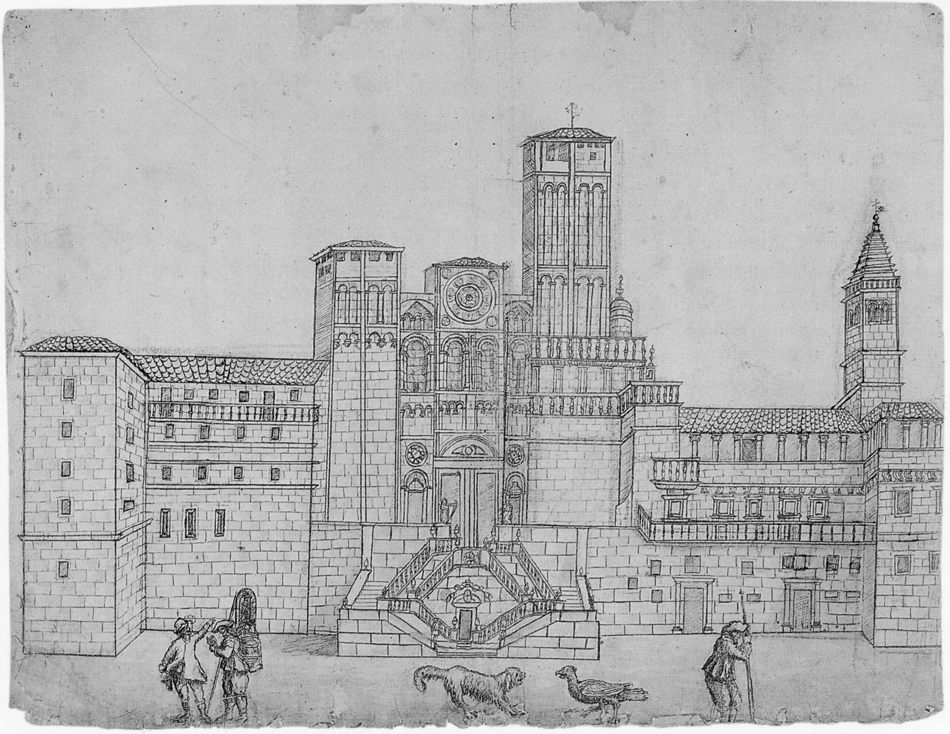

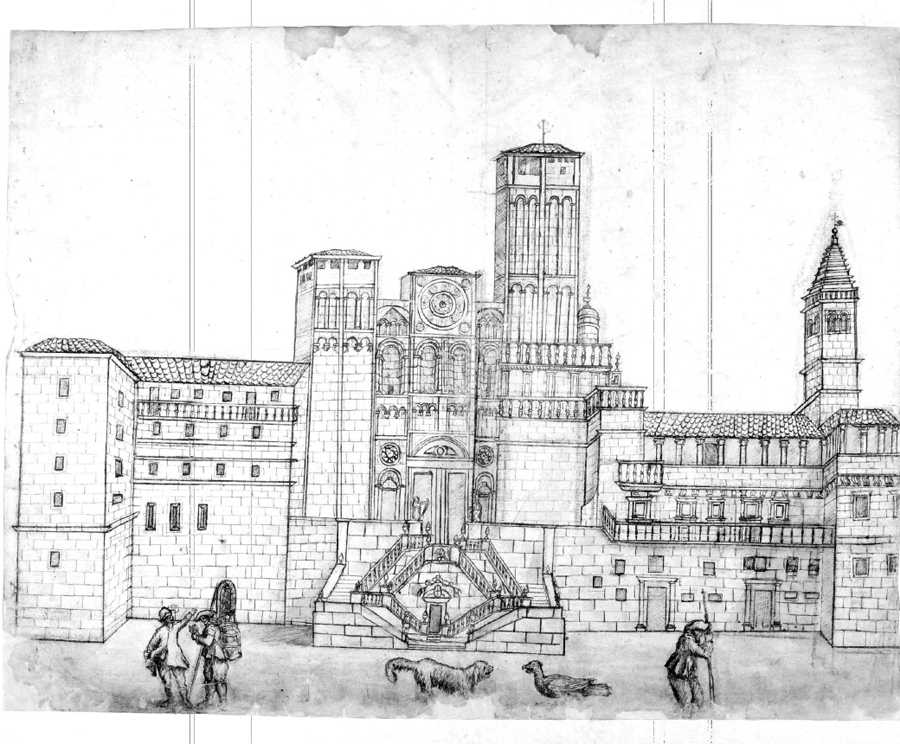

Two of the twelve drawings included in the Memorial merit our special attention. I refer to the urban views of the Obradoiro and Quintana squares, which show the precise topography of the cathedral buildings in 1657. This means that they show the Romanesque cathedral as it was before the radical Baroque reforms carried out on the building in the second half of the seventeenth century and in the first half of the eighteenth century,20 a fact already highlighted in 1976 by Gaya Nuño21 (figs. 1–2). These are the oldest existing drawings of the mediaeval cathedral that have survived to the present day, with the drawing of the Obradoiro square representing an exceptional document for studying the façade built by Maestro Mateo, which is studied in this paper.22

The purpose of these two drawings was to indicate the appearance of the cathedral on the date when the Memorial was written, and to support both the text, which analyses the Canon’s ideas for its reform, as well as the plans – now lost – which contained the author’s projects for the renovation. ← 17 | 18 → Indeed, the drawing of the Obradoiro had a series of plans stuck to the top, “which fold down (and) are in the air”,23 with the design of what had to be “added or extended”.24 Also, the drawing of the Quintana Square had a single fold-out plan, which in this case was stuck to the left-hand margin of the paper, the mark of which can still be seen, which is mentioned in the manuscript when the author states “the following drawing shows how it is today (referring to the façade in the Quintana) and that which is attached shows what must be added”.25

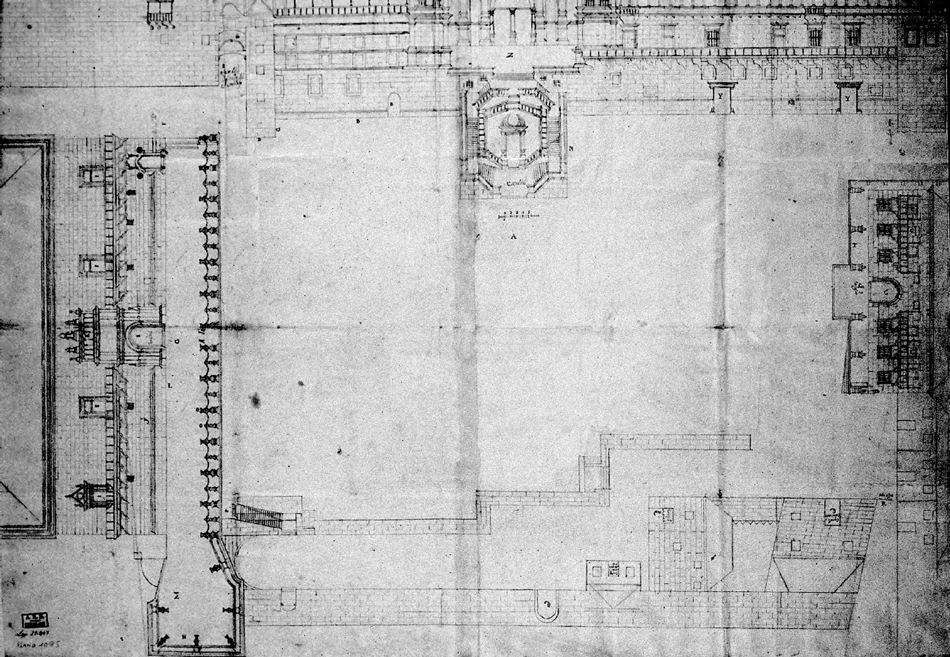

Fig. 1: J. de Vega y Verdugo: view of the Obradoiro Square.

Fig. 2: Black and white computer image of the Obradoiro Square based on the view by Vega y Verdugo. ← 18 | 19 →

Fig. 3: Modern-day view of the buildings and the square drawn by Vega y Verdugo.

The fact that both drawings, together with the project for the Obradoiro, were rediscovered separately from the manuscript in 1934 by Carro García26 leads to me suspecting that they were unstitched from the original by José María Zepedano some time around 1870 in order to publish two lithographs of the two façades.27 I also think the attached plans were lost at this time, as they were a nuisance.

In technical terms, both the view of the Obradoiro and the view of the Quintana were made by the author on site and not from memory, as it seems he did with other drawings in the manuscript which contain a large number of mistakes (fig. 3).28 These are two “natural views” or “urban profiles”, according to the classification ← 19 | 20 → of Fernando Marías for Spanish urban chorographies from the Modern Age,29 of the façades of the two most important squares in the city, drawn from several real and specific points of view, situated directly over the terrain, with a wide angle of view.30 The view of the Obradoiro was drawn by Vega y Verdugo from several points to the west of what was then called the Plaza del Hospital Real, close to where Rajoy Palace now stands but which did not exist at that time, and from more or less the retaining wall built in this area before the slope leading to the Huertas gate in the city wall (fig. 4).31 The drawing was made from two main points; the principal point on an axis with the entrance to the crypt and the central door of the cathedral (which would explain the head-on perspective of the staircase and the conical perspective of the sconces of the Archbishop’s Palace and the Chapter Palace), and another, secondary point from in front of the Archbishop’s Palace (which would explain the use of the cavalier perspective to give a three-dimensional effect to the cathedral’s towers, the main rose window and the Torre de la Vela, doing away with the vanishing effect provided by the conical perspective). Also, the vanishing point used and the ground plan in the drawing suggest that the artist was in an elevated position, roughly at the height of the cathedral’s door, something fre ← 20 | 21 → quent in the Italian urban representations in illustrations from the period.

Fig. 4: Plan of the Obradoiro Square by Francisco das Moas from 1745, showing the containing wall on the western side, from where Vega y Verdugo made his drawing (National Historic Archive, Consejos, MP and D, 1.095).

The fact that the drawing was made from different points in the square would also explain the errors in the representation of the Chapter Palace, whose far right section is partly hidden behind the College of San Jerónimo, meaning that the author had to move to the entrance of the Rúa do Franco to complete it. Another reason is the size of the paper used for the drawing, which forced him to reduce the size of the building shown, which here is also symmetrical with the Palace on the opposite side. In summary, the vanishing points used in the drawing are opposed as a result of the author’s lack of skill, leading to implausible perspectives. The reason for this incoherence lies in the application of a conical perspective in some parts, and the cavalier perspective in others, in order to give a sense of volume to the buildings.

The image, like that of the other square, is situated chronologically at a moment when paintings of urban landscapes were becoming an independent artistic genre in Europe.32 The author has drawn them first in carbon on two double folios of paper in situ in both squares, and then, we imagine in the comfort of the studio in his home, finished them with sepia and black ink. This suggestion is based on the fact that in Vega y Verdugo’s will from the third of August 1658, he declares that in his home there is a room “for painting” with five easels, and where I am convinced he completed the drawings from our manuscript.33 He acquired a love of painting during the years he lived in Rome, which would explain his technique, his concepts of symmetry and proportion included in the manuscript, and also his subsequent contacts with artistic circles in Compostela.

The layout of both urban views and the presence of typical characters from the city of Compostela is due to the fact that the author conceived them as an imitation of the Italian urban views he was fond of: in 1650 he bought seven framed “maps”34 and in 1661 “a map on paper”35 which may well have been choreographies of cities, and in 1670 the pilgrim and priest Domenico Laffi, from Bologna, gave him a collection of drawings by Italian painters he knew he would like, although he does not mention their theme.36 In effect, in the drawings of Compostela there is a clear influence of the paintings the author may have seen while he was in Italy and perhaps in Naples, due to his relationship with the Count of Oñate:37 for example, the urban scenes of the Sistine Library in the Vatican, from 1585–1590,38 or the equally anonymous scene of the Plaza Mayor de Madrid in Castel Nuovo dating from the middle of the seventeenth century. However, I think it is more likely that he was influenced by engravings of Roman buildings and squares that had been in fashion since the end of the fifteen hundreds, aimed at tourists, pilgrims and travellers, such as those by Etienne Dupérac, Philip Galle or Giovanni Battista Falda, amongst others.39 Out of the two, the view of the Obradoiro – despite lacking any type of scale – has especially notable qualities, and was described by Virginia Tovar as one of the most beautiful architectural Spanish drawings of the seventeenth century.40 ← 21 | 22 →

The mediaeval cathedral in the drawing of the Obradoiro

As already mentioned, the urban view of the Obradoiro Square shows the appearance of the façade that encloses the old Plaza del Hospital Real to the east at the time when the second part of the Memoria was produced in 1657, described by Vega y Verdugo as “one of the finest in Spain” (fig. 1).41 Specifically, it shows in certain detail three of the most representative buildings of the institutional and religious life of the city. I refer to the Archbishop’s Palace, the cathedral and the Chapter Palace, the last of which is referred to in the manuscript as “the Rooms of the Fabric and Chapter” (“los Quartos de la Fábrica y Cabildo”).42 Unfortunately, only the front part of the three buildings is shown, concealing the rear in order to do away with the problem of correctly decreasing the sizes of the most distant buildings by applying the laws of perspective. Similarly, we also see that greater attention has been paid to the drawing of the front of the cathedral, which is what really interested him for proposing his projects, suppressing information and even making mistakes in the way the other two buildings were represented.

Out of the three buildings that were drawn, the cathedral is the most transformed, with this representation constituting the only image that still remains of the late Romanesque façade built by Maestro Mateo at the end of the twelfth century as a monumental enclosure for the cathedral and to protect the magnificent sculptures of the Pórtico de la Gloria (compare figs. 1 and 3).43 It consists of a central front, which underwent a number of reforms in the Modern Age that are shown in the drawing, and was destroyed in 1738 when the architect Fernando de Casas created the current Baroque façade,44 and two towers of uneven height that were never completed. The front is laid out in three sections, with the central section being the widest, which correspond to the three interior naves of the cathedral. In the first level are the three entrance arches, which are not open how they were conceived by Maestro Mateo, who, however, had closed off the three interior arches of the Pórtico de la Gloria with wooden doors. Indeed, the external spans were reformed for the first time in 1520 by the master stonemason of French origin, Martín de Blas, author of the magnificent doorway of the Royal Hospital, following a design by Maestro Fadrique.45 The aim was to install four new wooden doors to close them off. This would lead to dividing the great central arch, measuring some eight metres,46 referred to in the document as the Trinidad arch, into two entrances to allow the two wooden doors to be installed. According to the contract, Martín de Blas divided it using a mullion made of jasper, supporting the two smaller arches it contained. The opening between the main arch and the two smaller arches were used to install a pane of glass or skylight that allowed light to shine into the ← 22 | 23 → cathedral and illuminate the Pórtico de la Gloria. Its final appearance must have been similar to the main entrance in the western façade of the cathedral of Ourense we can see today, which was also divided in the sixteenth century in the same way described in the contract for the entrance in Compostela.47

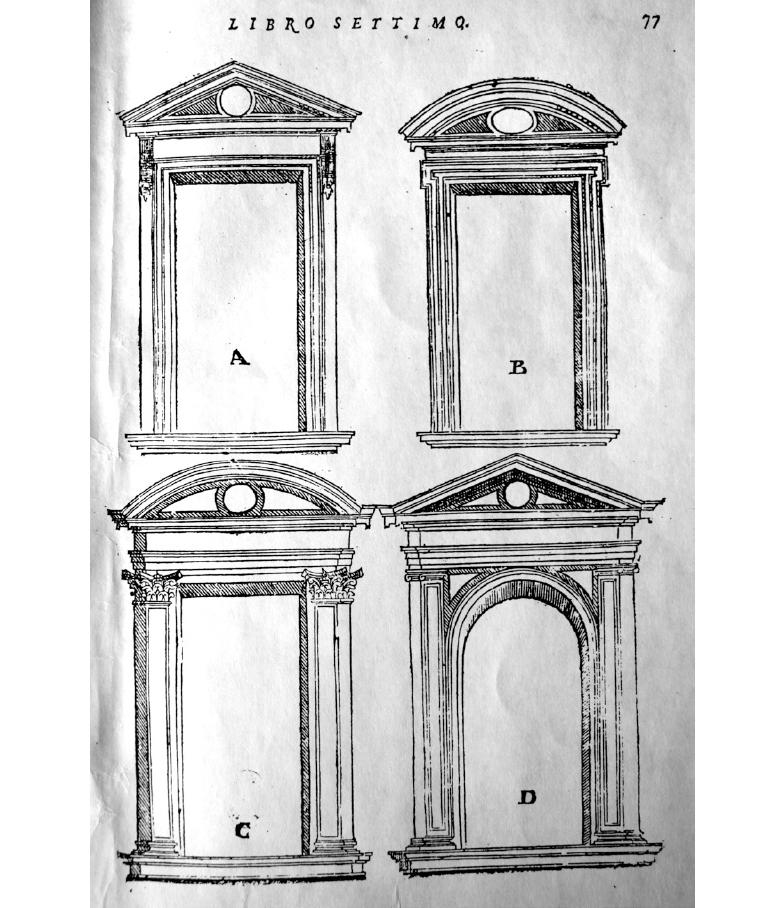

This layout does not correspond to what we see in the drawing, where the tympanum is decorated with a stone tondo in the style of the doors of Serlio (fig. 5). This, as Alfredo Vigo states, is due to a subsequent, undocumented reform, datable to the beginning of the seventeenth century, and possibly connected with the construction of the new staircase, which we will discuss later on in this paper.48 The tondo and the rest of the tympanum were probably perforated in order to allow light to shine through onto the Pórtico de la Gloria (fig. 2), a process which had already been proposed in the previous century, and which Fernando de Casas used in the Baroque façade.

Martín de Blas is also responsible for the reformation of the side arches, although in the drawing they still have their mediaeval appearance. He moved the wooden doors from the side arches of the Pórtico de la Gloria to the corresponding arches in the main façade,49 which must have had similar proportions, as well as installing glass windows, shown in the drawing and which may have led to the destruction of the mediaeval tympanums. A lack of information prevents us from knowing if other works were also carried out on both arches in the seventeenth century. However, I suspect Martín de Blas eliminated the mediaeval interior tympana from the side arches of the Pórtico de la Gloria as well and possibly opened the two circular windows in both arches. The aim of these interventions was to allow more light to enter the interior of the basilica.

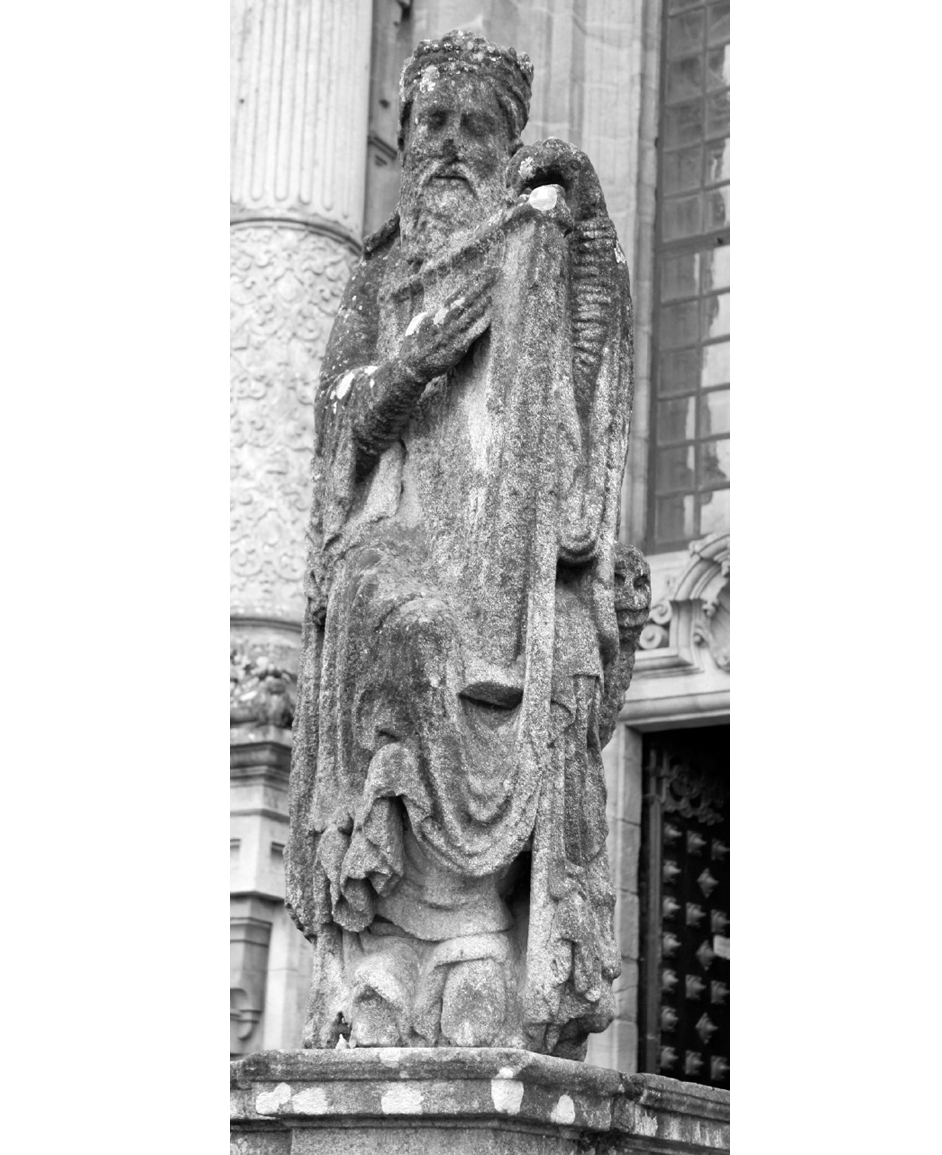

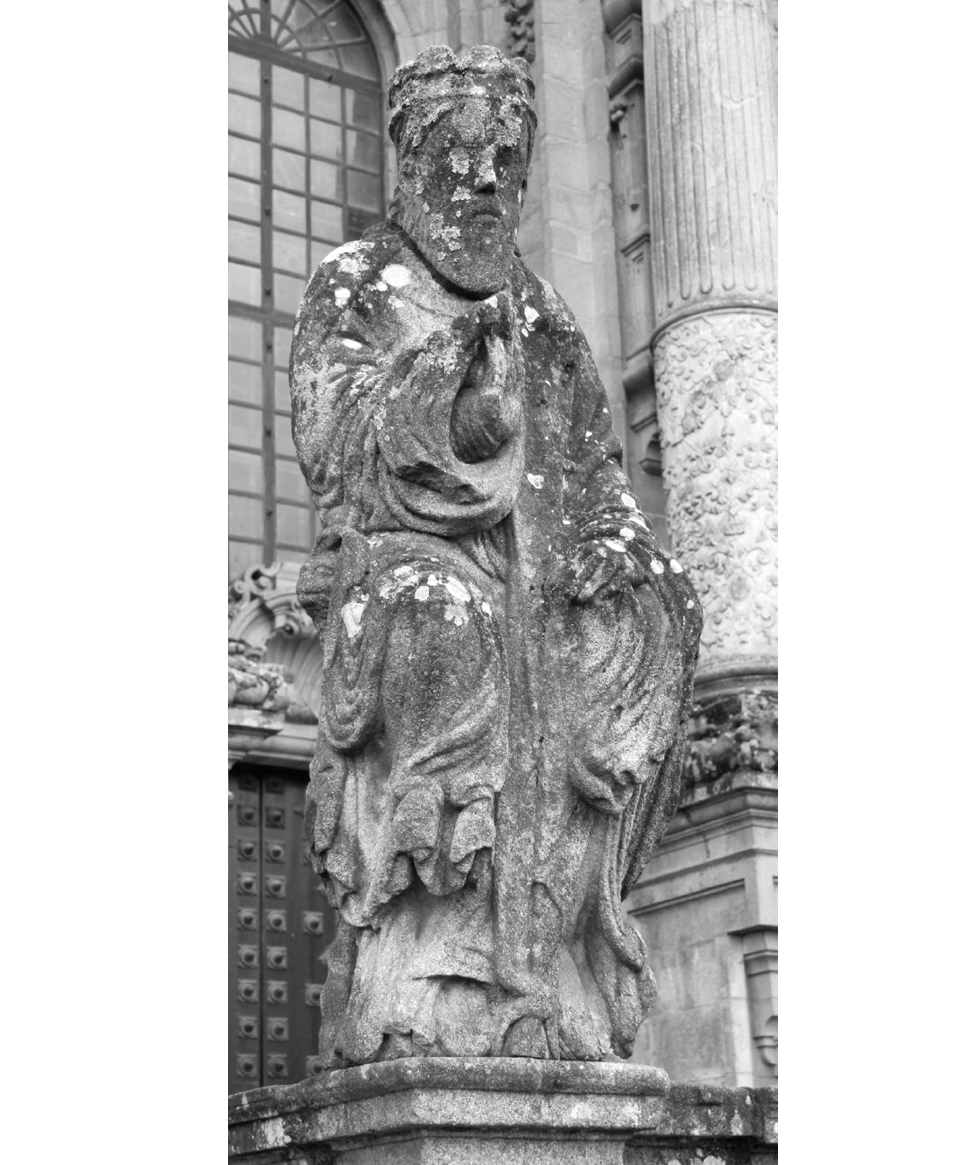

Both projects in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries led to the destruction of much of the three doorways created by Maestro Mateo, and the dismantling of at least part of its magnificent sculptural decoration. This is probably when the images of David and Solomon were moved onto the terrace, where there are seen in the drawing and still remain to this day (figs. 6–7).50 Here it is possible to clearly see two seated figures and the harp of the first, but not Solomon’s sceptre or his old head, as the original was lost and its current head is a later addition. According to Yzquierdo Perrín, both are column statues from the central door, which after being moved to their new position were re-carved at the back in order to complete them.51 ← 23 | 24 →

Fig. 5: Doors (Sebastian SERLIO, Tutte l’opere d’architetture et prospetiva, Venice 1619, Book VII, 77).

Fig. 6: Maestro Mateo, David.

Fig. 7: Maestro Mateo, Solomon.

Also, the two small Romanesque rose windows with a geometric design that stood above the side entrances were saved from the reforms, and are shown to be identical in the drawing. We know roughly where they were positioned due to the fact that their counterparts have survived inside the Pórtico de la Gloria, with all four allowing light to enter the side naves. Fortunately, the appearance of remnants of one or both has made it possible for a reconstruction to be made by Chamoso Lamas, now on display in the Cathedral Museum, and to know their correct size, a diameter of 1.95 metres (fig. 8).52 ← 24 | 25 → The current counter-façade still preserves the discharging arches that once contained the side doors and rose windows shown in the drawing, which facilitated the eighteenth-century Baroque reform.53

Fig. 8: Possible remnants of the rose windows from the Obradoiro square in the Cathedral Museum.

The second level ends with a cornice with simple semicircular arches based on what seem to be modillions. In the drawing they are distributed in four sections, one for each of the side naves and two for the main nave, separated by a central panel. Each section has three small arches, and they have been drawn with their order clearly defined, although without any type of decoration. Contradicting the simplicity of the drawing, Yzquierdo Perrín considers this location containing the cornice with five arches, richly decorated with busts of angels by Maestro Mateo in its interior, which now stands in the Cathedral Museum.54 However, after analysing a series of well-preserved mediaeval façades clearly influenced by Maestro Mateo, such as the façade of San Esteban de Ribas de Miño, in Saviñao, and Santa María de Cambre, I am inclined to think that the pieces of the Museum may have actually belonged to the eaves that once was located over the west side of the central entrance created by Maestro Mateo, and was destroyed, as I have already said, in the two interventions in the sixteenth century and early seventeenth century. This would be the reason why they do not appear in our drawing.55 ← 25 | 26 →

Fig. 9: The two interior discharging arches from the side windows of the tribune.

Fig. 10: Mediaeval storey that contained the large rose window of the Obradoiro façade, drawn by Vega y Verdugo.

Details

- Pages

- 432

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034314299

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035108583

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035198430

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035198447

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0351-0858-3

- Language

- German

- Publication date

- 2015 (July)

- Keywords

- Pilgrim's Guide Romanesque Baugeschichte Kirchenbau Nordspanische Skulpturen Fernando-Kreuz

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien. 2015. 432 S.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG