Nouvelles perspectives sur l’anaphore

Points de vue linguistique, psycholinguistique et acquisitionnel

Summary

Le propos du présent ouvrage est double : proposer un bilan épistémologique mettant au jour, parmi les modèles et approches proposés, ceux qui ont résisté au temps (et aux modes) ; pointer les aspects du phénomène anaphorique qui nécessiteraient des investigations complémentaires. En abordant l’anaphore de manière interdisciplinaire, ce livre vise aussi à décloisonner des domaines de recherche qui trop souvent s’ignorent : il rétablit le dialogue entre approches linguistiques, psycholinguistiques et acquisitionnelles, tout en faisant place aux perspectives orientées vers la logopédie et le TAL (Traitement Automatique du Langage).

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Couverture

- Titre

- Copyright

- Sur l’éditeur

- À propos du livre

- Pour référencer cet eBook

- Table des matières

- Avant-propos

- Indexicals and context: Context-bound pre-requisite(s), ongoing processing and aftermaths of the discourse referring act: Francis Cornish

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Text, discourse and (mainly) context, and their harnessing in indexical reference

- 3. Deixis, anaphora and “anadeixis”, and the distinctive indexical properties of various context-bound expression types

- 3.1. Deixis, anaphora and anadeixis

- 3.2. The distinctive indexical properties of a range of (English) phoric expression types

- 4. The contexts assumed and created by the operation of deixis, anadeixis and anaphora

- 5. Summary and Conclusions

- Acknowledgement

- References

- Anaphores et coréférences : analyse assistée par ordinateur: Frédéric Landragin

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Nature des chaînes de coréférence et problématiques associées

- 2.1. Les chaînes de coréférence et leurs maillons

- 2.2. Unités, relations et schémas pour l’annotation de chaînes

- 2.3. Types d’hypothèses linguistiques concernées

- 3. Visualisation de chaînes de coréférence

- 4. Calculs sur les chaînes de coréférence

- 5. Conclusion

- Références bibliographiques

- Annotation des expressions référentielles et profondeur de traitement: Michel Charolles

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Les expressions référentielles : approches linguistiques et annotation dans des corpus

- 2.1. Singularités de l’annotation manuelle

- 2.2. Etiquettes permettant d’identifier les référents

- 2.3. Difficultés dans l’affectation des indices référentiels

- 2.4. Sélection des expressions référentielles

- 2.5. Difficultés dans la sélection des référents auxquels peut renvoyer une expression anaphorique

- 3. Approches psycholinguistiques

- 3.1. Traitements à profondeur variable des ambiguïtés de rattachement syntaxique

- 3.2. Focalisation et profondeur de traitement des expressions référentielles

- 3.3. Traitement peu approfondi des pronoms

- 4. Discussion des données comportementales sur le traitement des pronoms

- 4.1. Polysémie des pronoms ambigus ?

- 4.2. Encombrement de la mémoire de travail et possible simplification du modèle référentiel

- 4.3. Incidence de la tâche et illusions sémantiques

- 5. Conclusion

- Références bibliographiques

- L’emploi du clitique ils à valeur indéterminée en français : entre interprétation anaphorique et interprétation existentielle: Laure Anne Johnsen

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Propriétés sémantiques et référentielles du clitique il

- 2.1. Morphologie et sémantique du pronom « il » dans le système des clitiques du français

- 2.2. il : une expression anaphorique marquant la continuité référentielle

- 3. Ils à valeur indéterminée : une interprétation anaphorique ?

- 3.1. L’anaphore indirecte

- 3.2. L’anaphore pronominale indirecte

- 3.3. Le traitement anaphorique de ils à valeur indéterminée dans les travaux antérieurs

- 3.4. Approches linguistiques alternatives

- 3.5. Approches psycholinguistiques

- 3.6. Approches typologiques

- 4. Cadre d’analyse et bilan intermédiaire

- 5. Etude empirique : ils à valeur indéterminée dans un corpus de français parlé spontané

- 5.1. Corpus et méthodologie

- 5.2. Tri des occurrences

- 5.3. Résultats

- 5.4. Discussion : la référence indéterminée de ils : de la dénotation d’une classe vague à l’expression d’un agent postiche

- 5.4.1. Les interprétations « universelles »

- 5.4.2. Les interprétations existentielles

- 5.4.3. Limites

- 6. Conclusion

- Références

- Ce que nous enseignent les « aphorismes » lexicalisés: Marie-José Béguelin

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Extension du phénomène

- 3. Symptômes d’autarcie

- 3.1. Indices d’ordre paradigmatique

- 3.2. Indices syntagmatiques

- 3.3. Indices sémantiques et référentiels

- 3.3.1. Caractère effaçable de l’indice.

- 3.3.2. Difficulté à restituer un catégorisateur précis.

- 3.3.3. Flottements possibles dans l’accord du participe passé.

- 4. Défis pour l’analyste

- 5. Facteurs déclenchant

- 5.1. Réinterprétation d’emplois anaphoriques indirects.

- 5.2. Réinterprétation d’emplois cataphoriques à longue distance.

- 5.3. Insertion paradigmatique favorable.

- 5.4. Phénomènes citationnels.

- 5.5. « Dérive générique ».

- 5.6. Euphémismes allusifs.

- 6. Perspectives

- Bibliographie

- Anaphores louches et dualités: Alain Berrendonner

- 1. But de cette étude

- 2. Anaphores louches

- 2.1. Cette appellation recouvre une espèce particulière d’anaphores dont (3) donne un exemple:

- 2.2. Lieu ou occupants ?

- 2.3. Individu collectif ou classe ?

- 2.4. Un objet ou son nom ?

- 2.5. Type ou classe ?

- 3. Anaphores pas louches…

- 3.1. C’est notamment le cas de (8)

- 3.2. D’autre part, Corminboeuf (2011) a proposé d’ajouter à la liste des anaphores louches celle de (9) :

- 4. Modélisation

- 4.1. Hypothèse I : anaphores associatives ?

- 4.2. Hypothèse II : la notion de dualité

- 5. Conclusion

- Références

- JANUS: A framework for studying noun-phrase anaphor resolution: Alan Garnham

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Anaphoric Reference: A Fundamental Question

- 3. The JANUS “Model”

- 3.1. Backwards-looking functions of anaphoric expression in JANUS

- 3.2. Forwards-looking functions of anaphoric expression in JANUS

- 3.3. Prediction from JANUS – looking back

- 3.4. Predictions from JANUS – looking forward

- 3.5. Predecessors of JANUS

- 3.6. Centering Theory

- 3.7. The Informational Load Hypothesis

- 3.8. Two major omissions of the ILH

- 4. Backward-looking functions of anaphoric expressions

- 5. Experimental Work on NP anaphora

- 5.1. The role of anaphoric form

- 5.2. Search Procedures for Different Types of Anaphor: Demonstratives vs Pronouns

- 5.3. Use of World Knowledge in Anaphor Interpretation

- 5.4. Use of Background Knowledge

- 5.5. Antecedentless Anaphors

- 5.6. Inferences based on Lexical Entries

- 5.7. Implicit Causality of Verbs

- 5.8. Early use of Implicit Causality Information

- 5.9. Social (Gender) Stereotypes

- 6. Conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Ambiguity avoidance in noun-phrase anaphora: The repeated name advantage: Wind Cowles & Laura Dawidziuk

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Overview of factors for NP anaphora

- 3. The Repeated Name Penalty

- 4. Ambiguity Avoidance and Antecedent Competitors

- 5. The Experiment

- 5.1. Methods

- 5.1.1. Participants

- 5.1.2. Design and Stimuli

- 5.1.3.Procedure

- 5.2. Predictions

- 5.3. Results

- 5.3.1. Subject NP anaphor

- 5.3.2. Added Predicate

- 6. General Discussion

- 7. Conclusion

- References

- Référence et démonstratifs… entre accessibilité et (dis)continuité ?: Marion Fossard

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Première Partie : Entre accessibilité… et (dis)continuité

- 2.1. Construction du matériel expérimental

- 2.2. Tâche 1 : Jugement d’acceptabilité

- 2.2.1 .Méthode

- 2.2.1.1. Participants

- 2.2.1.2. Plan expérimental et procédure

- 2.2.2. Résultats

- 2.2.3. Discussion

- 2.3. Tâche 2 : Continuation de fragments de texte

- 2.3.1. Méthode

- 2.3.1.1. Participants

- 2.3.1.2. Plan expérimental et procédure

- 2.3.2. Résultats

- 2.3.3. Discussion

- 3. Deuxième Partie : Entre accessibilité… et (dis)continuité

- 3.1. Matériel expérimental utilisé dans les expériences 1 et 2

- 3.2. Méthode (expériences 1 et 2)

- 3.2.1. Participants

- 3.2.2. Plan expérimental et procédure

- 3.2.3. Prédictions (expériences 1 et 2)

- 3.3. Résultats (expériences 1 et 2)

- 3.4. Discussion

- 4. Conclusion

- Remerciements

- Références

- L’anaphore à petits pas : remarques sur le pronom celui-ci anaphorique: Georges Kleiber

- 1. Introduction

- 2. L’enjeu

- 3. La pluralité n’est pas un trait définitoire

- 3.1. Les contre-exemples

- 3.2. Une double justification

- 3.2.1. La réponse de De Mulder (1999) : en termes de token-réflexivité

- 3.2.2. La réponse de Demol : en termes de topicalité

- 4. Pour le maintien de la pluralité

- 4.1. Deux conditions préalables

- 4.2. Réexamen des contre-exemples

- 4.3. Quelques justifications supplémentaires

- 5. Pour conclure

- Bibliographie

- L’anaphore démonstrative en français et en néerlandais : étude empirique de cas de divergence et leurs répercussions en L2: Gudrun Vanderbauwhede

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Différents processus anaphoriques liés au SN démonstratif français

- 3. Le SN démonstratif anaphorique en français et en néerlandais

- 3.1. Affaiblissement de la force instructionnelle du SNdém français par rapport au SNdém néerlandais

- 3.2. Des contraintes linguistiques plus générales influençant le fonctionnement du SN démonstratif en français et en néerlandais

- 3.3. Des normes stylistiques différentes

- 4. Le SN démonstratif anaphorique en français et en néerlandais en L2

- 5. Conclusion

- Bibliographie

- Comment des mères racontent-elles une histoire à leur enfant ? Usage des expressions référentielles dans le dialogue mère-enfant: Geneviève De Weck & Anne Salazar Orvig

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1 Deixis et anaphore : quelle conception pour étudier le langage adressé à l’enfant ?

- 2. Les études sur la référence chez les enfants

- 3. Pourquoi étudier les productions des mères ?

- 4. Méthodologie

- 4.1. Population

- 4.2. Situation d’observation et recueil des données

- 4.3. Axes d’analyse

- 4.4. Résultats

- 4.5. Première mention des référents

- 5. Reprises immédiates des référents

- 6. Réactivation des référents

- 7. Discussion et conclusion

- Références

- Résumés des chapitres, en français

- Résumés des chapitres, en anglais

- Rattachement institutionnel et adresses électroniques des auteurs

Avant-propos

Les éditrices du présent volume n’auraient peut-être jamais eu l’occasion de collaborer, ni même d’échanger des informations à propos de leurs travaux respectifs, si elles n’avaient occupé, dans l’annexe « ruelle Vaucher 22 » de l’Université de Neuchâtel, des bureaux contigus… ? À l’évidence, la topographie des locaux mis à disposition par l’université ne demeure pas sans effets sur le devenir de la recherche scientifique, ce dont témoigne la genèse du présent volume.

Tout a commencé le jour de novembre 2010 où Marion Fossard – auparavant professeure adjointe à l’Université Laval (Québec) – est arrivée à l’Université de Neuchâtel pour y occuper, à l’Institut des Sciences du langage et de la communication, une chaire d’orthophonie-logopédie nouvellement créée. Elle-même et son équipe se sont installées dans les bureaux jouxtant ceux qui, depuis 2008, abritaient le groupe de recherche animé par Marie-José Béguelin, alors professeure ordinaire de linguistique française et directrice de l’Institut1. Dès ce moment, les échanges informels entre l’équipe de logopédie et celle de linguistique française, sur le pas de porte des bureaux ou autour de la machine à café, ont joué un rôle de catalyseur, faisant émerger une réflexion et un projet communs.

Certes, les deux nouvelles collègues venaient d’horizons scientifiques différents (psycholinguistique expérimentale d’une part, linguistique descriptive du français d’autre part), mais elles s’étaient toutes deux intéressées de près à la thématique de l’anaphore ; elles avaient aussi, l’une et l’autre, entretenu des contacts avec trois spécialistes renommés du domaine, Francis Cornish, Michel Charolles et Georges Kleiber (signataires des chapitres 1, 3 et 10 de ce livre).

Marie-José Béguelin avait consacré une vingtaine de publications à l’anaphore en français, parues entre les années 1988 et 2000, dont certaines rédigées avec Denis Apothéloz et Alain Berrendonner. Elle y avait étudié ← VII | VIII → les phénomènes anaphoriques en contexte, dans une perspective écologique, avec pour objectif de rendre compte non seulement des emplois standard des marqueurs concernés (pronom personnel, élément zéro, SN démonstratif ou défini, SN incluant un adjectif anaphorique tel que premier, autre, etc.), mais aussi de leurs emplois non normatifs2. Depuis quelques mois, sa collaboratrice Laure Anne Johnsen avait entrepris une thèse sur l’approximation référentielle, réalisée dans le cadre d’un projet soutenu par le Fonds national suisse de la recherche scientifique (FNS), intitulé « Syndèse et asyndèse dans les routines paratactiques »3. Marie-José Béguelin avait également œuvré pour accueillir à l’Université de Neuchâtel, en tant que chercheuse visiteur, Gudrun Vanderbauwhede, auteure d’une thèse remarquée de l’Université de Louvain sur l’anaphore démonstrative, traitée dans une perspective à la fois contrastive et didactique4.

Quant à Marion Fossard, elle avait soutenu en 2001 à l’Université de Toulouse une thèse de doctorat intitulée Aspects cognitifs de l’anaphore pronominale: approche psycholinguistique et ouverture neuropsycholinguistique auprès de deux patients atteints de démence type Alzheimer ; elle avait conduit plusieurs études de psycholinguistique expérimentale sur la résolution des pronoms personnels et démonstratifs et, en collaboration notamment avec Francis Cornish, une étude sur l’emploi des pronoms dits indirects, en français et en anglais. Ses réseaux s’étendaient aux pays anglo-saxons : Grande-Bretagne (où elle a séjourné auprès d’Alan Garnham, signataire du chapitre 7), et aux États-Unis (où elle a travaillé avec Wind Cowles, co-auteure avec Laura Dawidziuk, du chapitre 8). Plus récemment, à l’Université Laval, elle ← VIII | IX → avait bénéficié d’une subvention « Nouveau Professeur » du Fonds Québécois de Recherche sur la Société et la Culture5, en vue de mener à bien une étude expérimentale sur la référence démonstrative (dont les résultats sont présentés au chapitre 9 de ce volume). Dans la foulée, elle s’apprêtait à soumettre au FNS un projet – accepté depuis – sur le thème « Discours et théorie de l’esprit : utilisation d’indices référentiels et prosodiques pour évaluer l’attribution de connaissances aux autres en situation d’interaction verbale »6.

S’ajoutait à cela le fait que Geneviève de Weck7 et Simona Pekarek Doehler, autres membres de l’ISLC, étaient également les auteures d’études importantes sur l’anaphore. Toutes les conditions semblaient donc réunies pour organiser en Suisse un colloque interdisciplinaire sur ce thème, donnant l’occasion d’une confrontation entre chercheurs de la jeune génération et spécialistes expérimentés. Le colloque en question s’est tenu à Neuchâtel les 4 et 5 avril 2012, avec le soutien du FNS et de la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences humaines de l’Université ; le présent volume constitue un prolongement des échanges scientifiques qui ont eu lieu à cette occasion.

Phénomène discursif éminemment complexe, l’anaphore met en jeu des mécanismes informationnels, mémoriels et inférentiels variés, que de nombreux modèles, linguistiques et psycholinguistiques, ont cherché à capter au cours des dernières décennies. Plusieurs sous-disciplines – syntaxe, sémantique, pragmatique, psycholinguistique, analyse conversationnelle, didactique, traitement automatique du langage (TAL), linguistique historique, typologie linguistique – se sont saisies de cette problématique qui, outre l’intérêt qu’elle présente pour la compréhension des stratégies référentielles et interprétatives en langue naturelle, fait aussi l’objet, sur le ← IX | X → terrain, d’importants enjeux sociétaux : remédiation des déficits rédactionnels en contexte scolaire, diagnostic des retards de langage ou des pathologies dégénératives, extraction informatisée des connaissances, traduction automatique… L’inflation des travaux sur l’anaphore, au cours des années 1980-2010, a toutefois fait obstacle à une mise en commun des acquis de la recherche, particulièrement nécessaire pourtant à l’heure où les modèles en concurrence sont confrontés à de nouveaux défis, notamment ceux posés par l’annotation et le traitement de vastes corpus, oraux et écrits.

Dans le contexte ainsi esquissé, nous avons souhaité entreprendre un bilan épistémologique, visant à mettre au jour, parmi les modèles et approches proposés, ceux qui ont résisté au temps (et aux modes). Ce faisant, il s’agissait aussi d’illustrer le cours pris par les recherches récentes sur les marqueurs référentiels dans différents sous-domaines des sciences du langage, en vue de faire émerger les aspects du phénomène anaphorique qui nécessitent des investigations complémentaires et, autant que possible, des collaborations transversales. En abordant la thématique de l’anaphore de manière interdisciplinaire, ce livre vise donc à décloisonner des domaines de recherche qui trop souvent s’ignorent ; il relance le dialogue entre approches linguistiques, psycholinguistiques et acquisitionnelles, tout en faisant place aux perspectives orientées vers la logopédie et le TAL (voir le chapitre 2, signé par Frédéric Landragin).

Au terme de cet avant-propos, nous tenons à exprimer toute notre reconnaissance au FNS, qui a soutenu et continue à soutenir nos recherches ; à la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences humaines de l’Université de Neuchâtel, sans le soutien financier de laquelle cet ouvrage n’aurait pu voir le jour ; à Emmanuelle Narjoux, pour la correction attentive des épreuves ; enfin à Marianne Grassi Moulin et Florence Waelchli, qui se sont chargées avec dévouement de la lourde tâche que représentait la mise en forme du volume.

Neuchâtel, janvier 2014

Marie-José Béguelin & Marion Fossard

NB. Le lecteur trouvera à la fin du livre les résumés des différents chapitres, en français et en anglais (pp. 357-371). ← X | 1 →

1Depuis le 1er août 2013, elle est devenue professeure honoraire.

2Cf. ici même, chapitres 5 et 6.

3Projet FNS 100012_122251 (requérante principale : Marie-José Béguelin ; corequérant : Alain Berrendonner ; collaborateurs : Gilles Corminboeuf, post-doctorant, et Laure Anne Johnsen, doctorante), relayé en juin 2013 par le projet 100012_146773 « Marqueurs corrélatifs entre syntaxe et analyse du discours » (requérante principale : Marie-José Béguelin ; corequérant : Alain Berrendonner ; collaborateurs : Pascal Montchaud, doctorant, et Laure Anne Johnsen, collaboratrice scientifique). Voir chapitre 4.

4Le séjour a eu lieu au semestre de printemps 2012. Cf. chapitre 11, ainsi que Vanderbauwhede, G. (2012). Le déterminant démonstratif en français et en néerlandais. Théorie, description, acquisition. Berne: Peter Lang.

5FQRSC, projet 2008-NP – 120525 « Le traitement des expressions démonstratives anaphoriques : implications pour la cohérence du discours » (requérante principale: Marion Fossard). .

6Projet 140269, qui a démarré en septembre 2012 (requérante principale : Marion Fossard ; collaborateurs : Arik Lévy, post-doctorant ; Lucie Rousier-Vercruyssen, doctorante, et Mélanie Sandoz, doctorante).

7Co-auteure, avec Anne Salazar Orvig, du chapitre 12.

Indexicals and context: Context-bound pre-requisite(s), ongoing processing and aftermaths of the discourse referring act

FRANCIS CORNISH, Université de Toulouse Jean-Jaurès and CLLE-ERSS, UMR 5263, France

1.Introduction

In this chapter, I would like to review the fundamentals (as rugby commentators often say), which often seem to be “taken as read” or even ignored in much work on indexical reference: the question of the nature of the various basic types of indexical referring procedures (here, pure deixis, “anadeixis” and discourse anaphora), and their realization via tokens of the different types of indexical expressions (demonstratives, definite NPs, 3rd person pronouns, and so on) – and in particular, their sensitivity and contribution to the context prevailing at the point of use. More specifically, the context which each type of referring procedure assumes and how each of them modifies that context subsequent to the point of use.

There are two main aspects to this question: first, the particular bundle of discourse-referential properties which characterizes each type of indexical expression1: as a function of its distinctive array of semantic-pragmatic properties, the use of a token of each of these expression types, in conjunction with its host predication, presupposes a distinct kind of discourse context, and in turn, creates a particular kind of context for the ensuing discourse; and second, a characterisation of the more general notion of discourse context, over and above the use of any given type of indexical. We will see that it is not in fact simply the use of a token of a ← 1 | 2 → given indexical expression type per se that presupposes one or other type of prior context and that serves to shift that context in specific ways, but rather its use in realizing canonical dexis, “anadexis” (here ‘strict’ anadeixis, recognitional anadeixis and discourse deixis), or canonical anaphora2. So an exploitation of the language-system/language-use distinction, often conflated in studies of these phenomena, is in fact indispensable (cf. Bach, 2004). The corpus of attested examples used (both written and (originally) spoken) is chiefly drawn from the weekly UK magazine, Radio Times.

2.Text, discourse and (mainly) context, and their harnessing in indexical reference

In characterizing utterance-level, context-bound phenomena such as the use of pronouns and other indexical expressions, it’s useful to start by drawing a three-way distinction amongst the dimensions of text, context and discourse. The notions ‘text’ and ‘discourse’ are frequently treated in the literature as virtually identical; or alternatively, ‘text’ is often viewed as relating to a stretch of written language, and ‘discourse’ to a spoken one. What I am calling text embraces the entire perceptible trace of an act of utterance, whether written or spoken. As such it includes paralinguistic features of the utterance act, as well as non-verbal semiotically relevant signals such as gaze direction, pointing and other gestures, etc. –i.e. not just the purely verbal elements. Text in this conception is essentially linear, unlike discourse, which is the product of the hierachically-structured, situated sequence of utterance, indexical, propositional and illocutionary acts carried out in pursuit of some communicative goal. ‘Discourse’, then, is the ever-evolving, revisable interpretation of a particular communicative event, which is ← 2 | 3 → jointly constructed mentally by the discourse participants as the text and a relevant context are perceived and evoked (respectively). Table 1 below summarises this distinction.

Text | Context | Discourse |

The connected sequence of verbal signs and nonverbal signals in terms of which discourse is co-constructed by the discourse partners in the act of communication. |

The context (the domain of reference of a given text, the co-text, the discourse already constructed upstream, the genre of speech event in progress, the socio-cultural environment assumed by the text, the interactive relationships holding between the interlocutors at every point in the discourse, and the specific utterance situation at hand) is subject to a continuous process of construction and revision as the discourse unfolds. It is by invoking an appropriate context that the addressee or reader may create discourse on the basis of the connected sequence of textual cues that is text. |

The product of the hierarchical, situated sequence of utterance, indexical, propositional and illocutionary acts carried out in pursuit of some communicative goal, and integrated in a given context. |

Table 1: The respective roles of text, context and discourse (Cornish 2010, Table 1, p. 209, revised)

Context is also conceived here in cognitive terms in relation to the mental representations which speaker and addressee are jointly developing as the communication proceeds, and as such it is continuously evolving. The context in terms of which the addressee or reader creates discourse on the basis of text comprises at least the following aspects: the domain of reference of a given text (including of course the local or general world knowledge that goes with it), the surrounding co-text of a referring expression, the discourse already constructed upstream of its occurrence, the genre of speech event in progress, the socio-cultural environment assumed by the text, the interactive relationships holding between the interlocutors at every point in the discourse, and the specific utterance situation ← 3 | 4 → at hand3. It is subject to a continuous process of construction and revision as the discourse unfolds. The most central of these aspects is the context of utterance of each discourse act: this functions as a default grounding “anchor” for the discourse being constructed as each utterance is produced. So context is the mediating, “anchoring” or grounding dimension of any act of communication. In simple terms: “Text” + “Context” ⇒ “Discourse”. See Widdowson (2004) for a similar three-way distinction, and also Auer (2009).

Now, to what use(s) is context put in the act of utterance – in other words, what is or are its raison(s) d’être ? Well, the most important of these, as already pointed out, is to ground the discourse being co-constructed – first and foremost in the context of utterance, but also in terms of a genre (type of speech event) and a topic domain. Relevant context is what enables discourse to be created on the basis of text: it is through the invocation of a relevant context that addressees may draw inferences (conversational implicatures in Gricean terms) on the basis of the speaker’s uttering what he or she utters. This very important feature of the use of language allows speakers to be as economical as possible in their use of the coded language system in creating text, as a function of their current communicative goals (cf. Clark, 1996: 250-251). They can rely on their addressees to a great extent to ‘fill in’ the many gaps that may be left in the textual realization of their intended message4.

Context is also what enables the crucial integration of basic discourse units (representing discourse acts or moves) into a higher-level discourse unit. As far as context-bound (indexical) reference is concerned, the immediately preceding co-text, as well as the discourse constructed following its processing, are needed in order to provide the cues required for the addressee to base his/her inference of a potential referent on; and the co-text and discourse context enable the speaker to choose an appropriate ← 4 | 5 → context-bound expression to allow the addressee to retrieve a given referent accessible via the prior discourse. The prosodic structure associated with these prior utterances also plays a crucial role in the realization of given anaphoric expressions, as well as in their interpretation potential. See Roberts (2004) on these aspects.

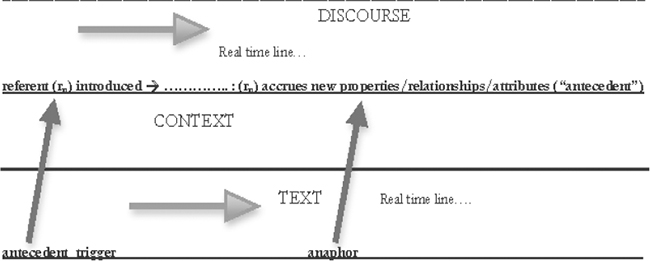

Now, exploiting this three-way distinction, my hypothesis is that there is a complex interaction between the dimensions of text and discourse, mediated by context, in the operation of indexical reference. What I call the antecedent trigger (an utterance token, a percept or a semiotically-relevant gesture – all falling under my definition of text) contributes the ontological category or type of the anaphor’s referent; but the actual referent itself and its characterization are determined by a whole range of factors: what will have been predicated of it up to the point of retrieval, the nature of the coherence/rhetorical relation invoked in order to integrate the two discourse units at issue, and the particular character of the indexical or “host” predication. All these factors come under the heading of discourse, under my definition (Table 1). So contrary to the classical conception of discourse anaphora, whether the referent retrieved via a given anaphor has been directly and explicitly evoked in the prior or following co-text (in the case of cataphora) provides neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for its existence. For the natural language user, there is no simple matching process between two separate expressions (textual antecedent and anaphor), independently of their respective semantic-pragmatic environments, as under the traditional account.

Figure 1 is a schematic representation of the distinction between antecedent trigger and antecedent as I conceive it, as well as of the different domains in which each operates (respectively, those of text and discourse): ← 5 | 6 →

Figure 1: Discourse, context, text and the relationship between “antecedent-trigger”, “referent”, “antecedent” and “anaphor”

As is evident from this representation, Discourse and Text are schematized as running in parallel with each other – both subject to a time line. Text and Context feed into Discourse. The antecedent trigger is part of some particular text (broadly construed, as we have seen) and may evoke a referent, which is mentally represented within the discourse (see the first dark arrow pointing obliquely upwards through the mediating ‘Context’ layer towards the discourse representation above). This representation then accrues certain properties, relations etc. as these are predicated of it in the ensuing text. A subsequently occurring anaphor (a linguistic expression) together with its host predication as a whole in the following co-text then enables the addressee or reader to access this representation as it has evolved up to the point of retrieval. This is an illustration of Heraclitus’s famous point that “you never step into the same river twice”. In this schema, there is no direct intra-textual relation posited between antecedent trigger and anaphor, as under the classical conception of anaphora (see Cornish, 2010 for further discussion). ← 6 | 7 →

3.Deixis, anaphora and “anadeixis”, and the distinctive indexical properties of various context-bound expression types

3.1.Deixis, anaphora and anadeixis

As far as deixis and anaphora are concerned, I view these as complementary discourse procedures which the users exploit in building, modifying and accessing the contents of mental models of a discourse under construction within the minds of speaker and addressee (or writer and reader in the written form of language). They are essentially attention-coordinating, discourse-management devices.

Details

- Pages

- X, 374

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034315456

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035195446

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035195453

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035202823

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0352-0282-3

- Language

- French

- Publication date

- 2014 (October)

- Keywords

- Bilan épistémologique Logopédie Phénomène discursif

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 374 p.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG