Summary

In this book, authors from the fields of cultural studies, cinema studies, history and art history examine the concept of spectacle in the German context across various media forms, historical periods and institutional divides. Drawing on theoretical models of spectacle by Guy Debord, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, Jonathan Crary and Michel Foucault, the contributors to this volume suggest that a decidedly German concept of spectacle can be gleaned from critical interventions into exhibitions, architectural milestones, audiovisual materials and cinematic and photographic images emerging out of German culture from the Baroque to the contemporary.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

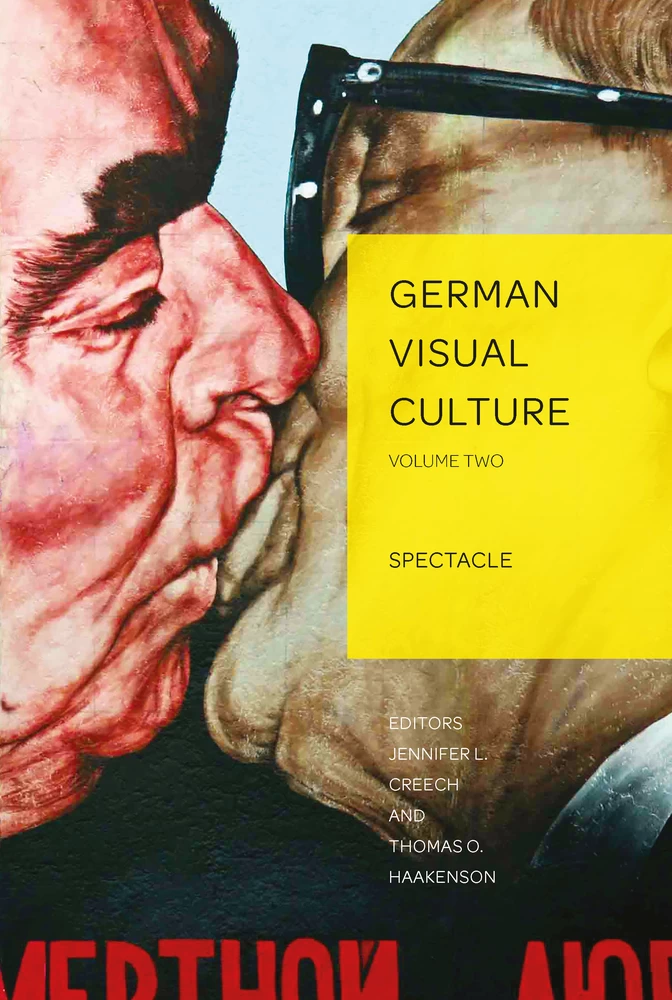

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Introduction: What is “German Spectacle”?

- Opening a Window to the Devil: Religious Ritual as Baroque Spectacle in Early Modern Germany

- Bauhaus Spectacles, Bauhaus Specters

- Live on the Air, Live on the Ground: The “Chamberlin Flight” as Spectacular Event, June 1927

- Berlin in Light: Wilhelmine Monuments and Weimar Mass Culture

- Spectacles in Everyday Life: The Disciplinary Function of Communist Culture in Weimar Germany

- Spectacular Settings for Nazi Spectacles: Mass Theater in the Third Reich

- Gudrun is Not a Fighting Fuck Toy: Spectacle, Femininity and Terrorism in The Baader-Meinhof Complex and The Raspberry Reich

- Spectacular Architecture: Transparency in Postwar West German Parliaments

- Beyond the Global Spectacle: Documenta 13 and Multicultural Germany

- The Spectacle of Terrorism and the Threat of Theatricality

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series index

| vii →

Jacob M. Baum – Opening a Window to the Devil: Religious Ritual as Baroque Spectacle in Early Modern Germany

1.1 Mass of St Gregory by Wolf Traut (1510).

1.2 Medieval altar. Photo courtesy of author.

1.3 Medieval altar. Photo courtesy of author.

Elizabeth Otto – Bauhaus Spectacles, Bauhaus Specters

2.1 Photographer unknown, Untitled (Seated man in Marcel Breuer armchair later titled T1 1a), n.d., c. 1923. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Getty Research Institute.

2.2 Albert von Schrenck-Notzig, The Medium Eva C. with a Materialization on her Head and a Luminous Apparition Between her Hands, 1912. Gelatin silver print. Collection of the Institut für Grenzgebiete der Psychologie und Psychohygiene, Freiburg im Breisgau.

2.3 Paul Klee, Ghost of a Genius [Gespenst eines Genies], 1922. Oil transfer and watercolor on paper mounted on card. Collection National Galleries Scotland.

2.4 Paul Citroen, Spiritualist Séance, 1924. Watercolor and pen and ink on paper. Collection of the Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. ← vii | viii →

2.5 László Moholy-Nagy, Untitled [fgm 163], 1926. Photogram on developing paper mounted on cardboard. Collection of the Museum Folkwang, Essen. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Brían Hanrahan – Live on the Air, Live on the Ground: The “Chamberlin Flight” as Spectacular Event, June 1927

3.1 Front page of the 8-Uhr Abendblatt, June 4, 1927.

Paul Monty Paret – Berlin in Light: Wilhelmine Monuments and Weimar Mass Culture

4.1 Adolf Brütt, Friedrich III, 1903. Photo courtesy of the Nordsee Museum Husum.

4.2 Photographer unknown (Osram-Photodienst), from the series Berlin im Licht, 1928. Gelatin Silver Print. Photo courtesy of Berlinische Galerie, Fotographische Sammlung.

4.3 E. Marcuse, “Berlin im Licht,” cover of Zeitbilder. Beilage zur Vossischen Zeitung (Berlin), no. 42. October 14, 1928. Photo courtesy of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

4.4 Photographer unknown (Osram-Photodienst), from the series Berlin im Licht, 1928. Gelatin Silver Print. Photo courtesy of Berlinische Galerie, Fotographische Sammlung.

4.5 Artist unknown, “Berlin im Licht,” Die Rote Fahne (Berlin), October 14, 1928, p. 2. ← viii | ix →

4.6 Naum Gabo, “Vorschlag zur Lichtgestaltung des Platzes vor dem Brandenburger Tor Berlin,” 1928. From Bauhaus 2, no. 4 (1928). The Work of Naum Gabo © Nina & Graham Williams. Photo courtesy of the Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin.

4.7 Artist unknown (Schmitt), “Licht, dein Tod,” poster, c. 1944. Photo courtesy of the Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University.

Sara Ann Sewell – Spectacles in Everyday Life: The Disciplinary Function of Communist Culture in Weimar Germany

5.1 Agitprop Troupe “Kurve Links,” n.d. (c. 1932). Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der ehemaligen DDR im Bundesarchiv, Berlin (hereafter, SAPMO-BA), Bild Y 1-371/81.

5.2 Red Front Fighting League, August 1925. SAPMO-BA, Bild Y 1-55/00N.

5.3 Antifascist men, Berlin, May 1, 1931. SAPMO-BA, Bild Y 1-11838.

5.4 Electioneering in Hamburg, April 1932. SAPMO-BA, Bild Y 1-1586/7.

Nadine Rossol – Spectacular Settings for Nazi Spectacles: Mass Theater in the Third Reich

6.1 Dietrich Eckhart Open Air Theater, Berlin, 1939. Bundesarchiv Bild, 145, P019137. ← ix | x →

6.2 Loreley, Thingspiel site 1935/36, St Goarshausen. Courtesy of Stadtarchiv St Goarshausen.

6.3 Loreley, Thingspiel arena completed, St Goarshausen. Courtesy of Stadtarchiv St Goarshausen.

6.4 First European Youth Meeting in 1951, Loreley site, St Goarshausen. Bundesarchiv Bild, 145, 00010546.

Jennifer L. Creech – Gudrun is Not a Fighting Fuck Toy: Spectacle, Femininity and Terrorism in The Baader-Meinhof Complex and The Raspberry Reich

7.1 Ensslin reading Trotsky and debriefing a young male recruit. The Baader-Meinhof Complex, Dir. Uli Edel, Constantin Film Production, 2008.

7.2 The Baader-Meinhof Complex, Dir. Uli Edel, Constantin Film Production, 2008.

7.3 “Fuck me, for the Revolution!” The Raspberry Reich, dir. Bruce LaBruce, Jürgen Brüning Filmproduktion, 2004.

7.4 “Che.” The Raspberry Reich, dir. Bruce LaBruce, Jürgen Brüning Filmproduktion, 2004.

7.5 “The revolution is my boyfriend!” The Raspberry Reich, dir. Bruce LaBruce, Jürgen Brüning Filmproduktion, 2004.

Deborah Ascher Barnstone – Spectacular Architecture: Transparency in Postwar West German Parliaments

8.1 Spectators watching the first parliamentary session in Bonn, September 7, 1949. Bundesbildstelle, Berlin. ← x | xi →

8.2 Inside the Schwippert plenary chamber looking through one of the large glass walls to the courtyard. Schwippert Archiv, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg.

8.3 The entry facade of the Behnisch Bundeshaus in Bonn. Behnisch & Partner. Photographer: Christian Kandzia.

8.4 Behnisch study of internal spatial transparency at the Bundeshaus. Behnisch & Partner. Photographer: Christian Kandzia.

8.5 Front elevation of the renovated Reichstag looking through to the plenary chamber. Foster & Partners. Photographer: Nigel Young.

Heather Mathews – Beyond the Global Spectacle: Documenta 13 and Multicultural Germany

9.1 Theaster Gates, installation view of 12 Ballads for the Huguenot House, 2012, courtesy Kavi Gupta, Chicago/Berlin.

9.2 Goshka Macuga, detail of Of what is, that it is, of what is not, that is not I, 2012, wool tapestry, 520 × 1740 cm, courtesy of the artist and Kate MacGarry, London.

9.3 Gunnar Richter, Dealing with the Era of National Socialism – A Regional Study of a Crime in the Final Phase of World War II. Methods of Researching, 1981/2012, slideshow with sound. Photo courtesy of the artist. ← xi | xii →

Brechtje Beuker – The Spectacle of Terrorism and the Threat of Theatricality

10.1 Gerhard Richter, September (2005). Copyright Galerie Richter.

10.2 Blurring spatial boundaries in Gotteskrieger (2005). Copyright Wilfried Böing Nachlass, Berlin.

| 1 →

Introduction: What is “German Spectacle”?

The present volume is the second in the German Visual Culture series, which seeks to highlight work on visual culture done within the broad and expanding field of German Studies. Many of the following essays were culled from a series of panels at the German Studies Association (GSA) conference in 2012, a panel devoted to a cross-disciplinary and intermedia examination of spectacle within German contexts. These presentations on “German spectacle” were not limited by geography nor to only those manifestations of spectacle within the historic or contemporary boundaries of the German nation state. Neither was the concept of “German spectacle” located exclusively in specific language or cultural communities, as in those communities who speak or identify with the German language. Finally, the presentations did not define themselves through a focus on a single medium of expression, such as photography, painting, or theater. Such a broad framing begs the question, what is “German spectacle”?

The initial call for presentation proposals for the GSA panel and a subsequent call for contributions for this volume were purposefully and productively open, refusing to answer the question of “German spectacle” directly:

Details

- Pages

- XII, 306

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034318037

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035306545

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035397789

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035397796

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0654-5

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (August)

- Keywords

- German culture German cinema German art

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2015. XII, 306 pp., 10 coloured ill., 29 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG