Law and Popular Culture

A Course Book (2nd Edition)

Summary

Each chapter takes a particular legally themed film or television show, such as Philadelphia, Dead Man Walking, or Law and Order, treating it as both a cultural text and a legal text.

The new edition has been updated with new photos and includes greater emphasis on television than in the first edition because there are so many DVDs of older TV shows now available.

Law and Popular Culture is written in an accessible and engaging style, without theoretical jargon, and can serve as a basic text for undergraduates or graduate courses and be taught by anyone who enjoys pop culture and is interested in law. An instructor’s manual is available on request from the publisher and author.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Praise for Law and Popular Culture

- Praise for the First Edition of Law and Popular Culture

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Part I : Law, Lawyers, and The Legal System

- 1. Introduction to Law and Popular Culture

- 1.01 What this book is about

- 1.02 Definitions of “popular culture” and “popular legal culture”

- 1.02.1 The double meaning of “popular culture” and “popular legal culture”

- 1.02.2 Popular culture and high culture

- 1.03 Why a course in law and popular culture?

- 1.04 The relationship between popular culture and the law

- 1.04.1 Popular culture as reflection

- 1.04.2. Media effects

- 1.04.3 The cultural study of law

- 1.05 The (many) meanings of cultural texts

- 1.05.1 The feedback loop between law and popular culture— Miranda and Dragnet

- 1.05.2 The process of meaning-making—signifier and signified

- 1.05.3 Justitia’s blindfold

- 1.05.4 How do films and TV shows produce contested meanings?

- 1.05.5 Viewer-response theory

- 1.06 Filmmaking and reality

- 1.06.1 Micro and macro reality

- 1.06.2 Making legal films and TV shows seem “real”

- 1.06.4 Filmmaking today

- 1.06.5 Intertextuality

- Notes

- 2. The Adversary System and the Trial Genre: Assigned Film: Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

- 2.01 Anatomy of a Murder—The film and the book

- 2.02 The trial genre

- 2.03 Anatomy and the Production Code

- 2.03.1 Hays, Breen, and the Production Code

- 2.03.2 The decline and fall of the Production Code

- 2.03.3 Anatomy of a Murder and the Production Code

- 2.04 Justice, the adversary system, and Anatomy of a Murder

- 2.04.1 Law and justice

- 2.04.2 The adversary system

- 2.04.3 The inquisitorial system

- 2.05 Legal ethics in Anatomy of a Murder

- 2.06 Defenses to homicide in Anatomy of a Murder

- 2.06.1 The unwritten law

- 2.06.2 Insanity

- 2.06.3 Manslaughter

- 2.07 Film theory and cinematic technique in Anatomy of a Murder

- 2.07.1 Editing

- 2.07.2 Editing—Preminger’s long takes and deep focus

- 2.07.3 Distance and objectivity

- 2.07.4 Music

- 2.08 Review questions

- Notes

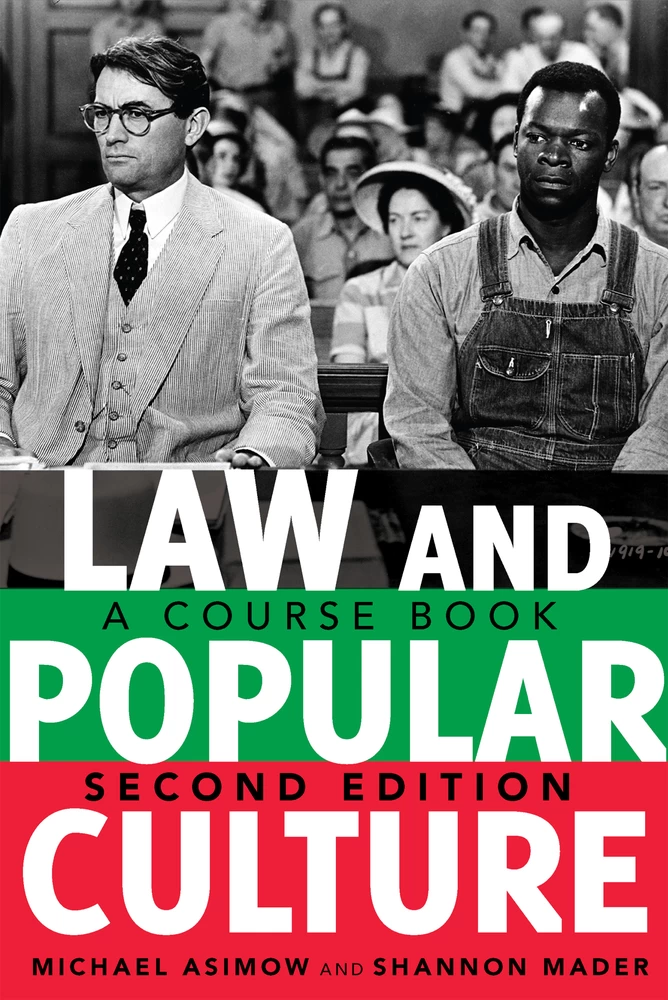

- 3. Lawyers as Heroes: Assigned Film: To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

- 3.01 To Kill a Mockingbird—The book and the film

- 3.02 Harper Lee and the Scottsboro boys

- 3.02.1 Messages from the author and filmmaker

- 3.02.2 The Scottsboro boys

- 3.03 Lawyers as heroes

- 3.03.1 The revisionist view of Atticus Finch

- 3.03.2 Heroic intertextuality—Young Mr. Lincoln and Mockingbird

- 3.04 Tom Robinson was clearly innocent, right?

- 3.05 The trial strategy of Atticus Finch

- 3.06 Atticus Finch and Boo Radley

- 3.07 Filmic analysis of Mockingbird

- 3.07.1 Robert Mulligan

- 3.07.2 Memories of childhood

- 3.07.3 Between two worlds—Childhood and law

- 3.08 Melodrama and Mockingbird

- 3.08.1 The melodramatic mode in American movies

- 3.08.2 Melodrama in films with racial themes

- 3.09 Review questions

- Notes

- 4. Lawyers as Villains: Assigned Film: The Verdict (1982)

- 4.01 The Verdict—Book and film

- 4.01.1 David Mamet and Sidney Lumet

- 4.01.2 Paul Newman

- 4.02 Public opinion of lawyers

- 4.03 Bad lawyers in the movies

- 4.04 The relationship between works of pop culture and public attitudes—The cultivation effect

- 4.04.1 Popular culture as follower of public opinion

- 4.04.2 Popular culture as leader of public opinion

- 4.04.3 The cultivation effect

- 4.04.4 Studies of the cultivation effect

- 4.04.5 Lawyers on television versus lawyers in the movies

- 4.04.6 Viewer response theory

- 4.05 Ethical problems in The Verdict

- 4.05.1 Witness coaching

- 4.05.2 Ambulance chasing

- 4.05.3 The settlement offer

- 4.06 Legal errors in The Verdict

- 4.07 Redemption of lawyers

- 4.08 The two hemispheres of law practice

- 4.08.1 Distinguishing the hemispheres

- 4.08.2 Ethical issues in the two hemispheres

- 4.08.3 Contingent fees and hourly billing

- 4.09 Storytelling in The Verdict

- 4.09.1 Narrative and narration

- 4.09.2 The classical Hollywood style

- 4.09.3 Variables in narration—Subjectivity and restricted narratives

- 4.09.4 Narrative about narrative

- 4.10 Visual design in The Verdict

- 4.10.1. Interiors in The Verdict

- 4.10.2 The use of the color red

- 4.11 Review questions

- Notes

- 5. The Life of Lawyers: Assigned Film: Counsellor at Law (1933)

- 5.01 Elmer Rice and William Wyler

- 5.01.1 Elmer Rice

- 5.01.2 William Wyler

- 5.02 Lawyer movies of the early 1930s

- 5.03 The life of lawyers

- 5.03.1 A lawyer’s day

- 5.03.2 Lawyers and money

- 5.03.3 Simon & Tedesco

- 5.04 The character of George Simon

- 5.04.1 Simon as a lawyer

- 5.04.2 Simon as a human being

- 5.05 Religion, ethnicity, and class in Counsellor at Law

- 5.05.1 Religion and ethnicity

- 5.05.2 The Depression

- 5.05.3 Class

- 5.06 Jewish lawyers in popular culture

- 5.07 Ethical issues in Counsellor at Law

- 5.07.1 The stock tip

- 5.07.2 The Richter fee

- 5.07.3 Perjury in the Breitstein case

- 5.08 Composition in Counsellor at Law

- 5.09 Review questions

- Notes

- 6. Legal Education: Assigned Film: The Paper Chase (1973)

- 6.01 U.S. legal education

- 6.01.1 U.S. law school is graduate school

- 6.01.2 Harvard Law School

- 6.01.3 The Paper Chase and 1L—The movies and the books

- 6.01.4 The Paper Chase—See it before you go to law school?

- 6.02 The Socratic method

- 6.02.1 In defense of the Socratic method

- 6.02.2 Origins of the Socratic method—And its future

- 6.02.3 Calling on students

- 6.02.4 Kingsfieldism

- 6.02.5 Teaching professional skills

- 6.03 Gender and legal education

- 6.03.1 Guinier’s critique

- 6.03.2 Is there a gender gap?

- 6.03.3 Difference versus equality feminism

- 6.04 The economics of legal education

- 6.04.1 The cost of legal education—and of student loans

- 6.04.2 Law schools in competition

- 6.05 Sound design and composition in The Paper Chase

- 6.05.1 The functions of sound

- 6.05.2 Sound editing

- 6.05.3 Composition

- 6.06 Review questions

- Notes

- 7. Law on Television: Assigned Material: Boston Legal, Season 1, disk 1 (episodes 1–4)

- 7.01 Television—Business and culture

- 7.01.1 Commercials

- 7.02 Lawyers on television

- 7.02.1 Perry Mason

- 7.02.2 The Defenders

- 7.02.3 L.A. Law

- 7.02.4 After L.A. Law

- 7.02.5 Boston Legal and its ancestors

- 7.02.6 Female attorneys on Boston Legal

- 7.03 Narration on television

- 7.03.1 Series and serials

- 7.03.2 Commercial interruptions

- 7.03.3 Conditions of consumption

- 7.04 Bad lawyers on television

- 7.05 Sexual harassment

- 7.06 Ethical issues on Boston Legal

- 7.06.1 Conflict of interest

- 7.06.2 Competence

- 7.06.3 Truth telling

- 7.06.4 Obstruction of justice and witness tampering

- 7.07 When the lawyer is certain the client is guilty

- 7.07.1 Legal ethics and the guilty client

- 7.07.2 Telling false stories in narrative

- 7.07.3 The guilty client in pop culture

- 7.07.4 Defending the guilty

- 7.08 Dual plot structure on Boston Legal

- 7.09 Review questions

- Notes

- Part II : Criminal Justice

- 8. The Criminal Justice System: Assigned Television Show: Law & Order (Season 5, episodes 1–4)

- 8.01 The U.S. criminal justice process

- 8.01.1 Goals of the criminal process

- 8.01.2 Investigation and searches

- 8.01.3 The first appearance and the process of questioning a suspect

- 8.01.4 Preliminary hearing or grand jury

- 8.01.5 The criminal trial

- 8.02 Law & Order—the television show

- 8.02.1 Dick Wolf

- 8.02.2 The puzzling success of Law & Order

- 8.02.3 The politics of Law & Order

- 8.02.4 Ben Stone and Jack McCoy

- 8.02.5 Adam Schiff: The Voice of Moral Realism

- 8.03 Criminal law on Law & Order

- 8.03.1 Degrees of homicide

- 8.03.2 Self-defense and the battered woman syndrome

- 8.04 Prosecutorial discretion

- 8.05 The indeterminacy of past facts

- 8.06 Prosecutors and defense lawyers on Law & Order

- 8.06.1 Crime control on Law & Order

- 8.06.2 Prosecutors in popular culture

- 8.06.3 Criminal defense lawyers

- 8.06.4 Defending the guilty

- 8.07 Realism on Law & Order

- 8.07.1 The ordinary filmgoer’s conception of realism

- 8.07.2 How the spectator arrives at a conception of the real world

- 8.07.3 What seems realistic—Some generalizations

- 8.08 Narrative structure on Law & Order

- 8.09 Review questions

- Notes

- 9. The Jury: Assigned Film: 12 Angry Men (1957)

- 9.01 12 Angry Men—Prequel and sequel

- 9.02 Fonda’s “star” image and intertextuality in legal films

- 9.03 The jury in the trial film genre

- 9.04 Constitutional role of the American jury

- 9.05 Conflicting visions of the jury—The brighter vision

- 9.06 Conflicting visions of the jury—The darker version

- 9.06.1 Rationality of jury verdicts

- 9.06.2 Efficiency of the jury system

- 9.06.3 Juries worldwide

- 9.07 Empirical research on juries

- 9.08 Jury passivity

- 9.09 Race and gender discrimination in jury pools

- 9.09.1 Historic discrimination in selection of jury pools

- 9.09.2 The Batson rule

- 9.09.3 Jury consultants

- 9.10 Seeing the witnesses, finding the facts

- 9.11 Jury nullification

- 9.12 Direction and cinematography in 12 Angry Men

- 9.12.1 Camera placement and movement

- 9.12.2 Focus on one character while another speaks

- 9.12.3 Closeups and editing

- 9.13 Review questions

- Notes

- 10. Military Justice: Assigned Film: A Few Good Men (1992)

- 10.01 The film and the play

- 10.02 The military justice system

- 10.02.1 The Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ)

- 10.02.2 Command influence

- 10.02.3 Why is there a separate military justice system?

- 10.02.4 Accusing superior officers of crime

- 10.03 Military justice in popular culture

- 10.04 The following-orders defense

- 10.04.1 The law of following orders

- 10.04.2 Following orders in A Few Good Men

- 10.04.3 Abu Ghraib and the war on terror

- 10.04.4 The Milgram experiments

- 10.05 Daniel Kaffee

- 10.06 Female lawyers in the movies

- 10.06.1 Female lawyers—Yesterday and today

- 10.06.2 Favorable portrayals of women lawyers in the movies

- 10.06.3 Female lawyers in film—Rita Harrison

- 10.06.4 Negative treatment of women lawyers in contemporary film

- 10.06.5 Difference versus equality feminism

- 10.06.6 Female lawyers on television

- 10.06.7 Understanding the negative treatment of female lawyers in the movies

- 10.07 Cinematic technique in A Few Good Men

- 10.07.1 Sound editing

- 10.07.2 Rack focus in A Few Good Men

- 10.07.3 Lighting

- 10.08 Review questions

- Notes

- 11. The Death Penalty: Assigned Film: Dead Man Walking (1996)

- 11.01 The book and the movie

- 11.02 Death penalty movies

- 11.02.1 Political stance of death penalty movies

- 11.02.2 Redemption of the condemned

- 11.02.3 Transformation of the intermediary

- 11.03 Pictures at an execution

- 11.04 The voice of the victims

- 11.05 Purposes of the death penalty

- 11.05.1 Deterrence

- 11.05.2 Studies of deterrence

- 11.05.3 Incapacitation

- 11.05.4 Moral opposition to the death penalty and retribution

- 11.06 Judicial flip-flops on the death penalty

- 11.07 The death penalty in the United States—Law and practice

- 11.07.1 The risk that an innocent person will be put to death

- 11.07.2 Clemency

- 11.07.3 Racial disparities

- 11.07.4 Class discrimination

- 11.07.5 Quality of legal defense

- 11.07.6 Delays

- 11.07.7 Error rates

- 11.07.8 Costs and strains on the criminal justice system

- 11.08 The death penalty outside the U.S.

- 11.09 Filmic analysis of Dead Man Walking

- 11.09.1 Camera placement in Dead Man Walking

- 11.09.2 Collision montage in Dead Man Walking

- 11.10 Review questions

- Notes

- Part III: Civil Justice

- 12. The Civil Justice System: Assigned Film: A Civil Action (1998)

- 12.01 The civil justice process

- 12.01.1 Civil cases

- 12.01.2 Lawyers in civil cases

- 12.01.3 Pleadings in civil cases

- 12.01.4 Discovery

- 12.01.5 Managerial judges

- 12.01.6 Jury trial

- 12.01.7 Witnesses and evidence

- 12.01.8 Trial procedure

- 12.01.9 After the trial

- 12.02 The book and the movie—the real case against Beatrice and Grace

- 12.02.1 The docudrama form

- 12.02.2 The importance of films based on actual events

- 12.02.3 Adapting a book into a film

- 12.02.4 The lawyers

- 12.02.5 What really happened?

- 12.02.6 The counter-attack

- 12.03 Litigation problems in toxic tort cases

- 12.03.1 Complexity of toxic tort cases

- 12.03.2 Alternative ways to compensate victims of toxic torts

- 12.04 Litigation financing

- 12.05 Judges

- 12.05.1 Judges in popular culture

- 12.05.2 Judge Skinner

- 12.05.3 The rule of law

- 12.05.4 Political appointment and elections

- 12.05.5 Federal judges

- 12.06 Settlement negotiations

- 12.06.1 Schlichtmann’s negotiations in the Woburn case

- 12.06.2 Negotiation theory

- 12.07 Big business in the movies

- 12.08 Framing in A Civil Action

- 12.09 Review questions

- Notes

- 13. Civil Rights: Assigned Film: Philadelphia (1993)

- 13.01 Philadelphia—The cases and the film

- 13.01.1 The real-life inspiration of Philadelphia

- 13.01.2 Philadelphia—the film

- 13.02 Clients and lawyers—access to justice

- 13.03 LGBT lawyers in the movies

- 13.03.1 LGBT lawyers

- 13.03.2 The representation of LGBT characters in film

- 13.03.3 Queer Theory

- 13.04 Black lawyers in the movies

- 13.04.1 African Americans and the legal profession

- 13.04.2 Black lawyers in the movies and television

- 13.04.3 Blacks in the movies and television—1930 to 1970

- 13.05 Law firms

- 13.05.1 Philadelphia and the hemispheres of law practice

- 13.05.2 Economics of biglaw

- 13.05.3 Why big law got so big

- 13.05.4 Two models of law practice: Professionalism and business

- 13.05.5 Billable hours

- 13.05.6 Quality of work life

- 13.06 Law firms in the movies

- 13.07 Employment law and civil rights

- 13.07.1 At-will employment

- 13.07.2 Exceptions to the at-will rule—Good cause discharge

- 13.07.3 Public policy and at-will employment

- 13.07.4 Civil rights protection

- 13.07.5 Disability discrimination

- 13.07.6 Race and sex discrimination

- 13.08 Strange doings in Philadelphia

- 13.09 Filmmaking in Philadelphia

- 13.09.1 Framing and Composition

- 13.09.2 Lighting

- 13.09.3 Montage

- 13.10 Review questions

- Notes

- 14. Family Law: Assigned Film: Kramer vs. Kramer (1979)

- 14.01 The book and the film

- 14.02 The cultural context of Kramer vs. Kramer

- 14.02.1 Divorce

- 14.02.2 The backlash against feminism

- 14.02.3 The “sensitive male movement”

- 14.03 From the Hays Code to Kramer vs. Kramer

- 14.03.1 Divorce under the Hays Code

- 14.03.2 From the Hays Code to Kramer vs. Kramer

- 14.04 Ingredients of a classic divorce movie

- 14.05 Fault and no-fault divorce

- 14.05.1 Fault divorce

- 14.05.2 No-fault divorce

- 14.06 The law of child custody

- 14.06.1 The tender years presumption

- 14.06.2 The best interests of the child

- 14.06.3 Child custody in the movies

- 14.07 The family law process

- 14.08 Lawyer-client relationships in family law

- 14.09 Cinematic technique in Kramer vs. Kramer

- 14.10 Robert Benton

- 14.11 Review questions

- Notes

- References

- Stage Plays

- Movies

- Television Shows and Series

- Court Cases

- Index

| ix →

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution to this book by Norman Rosenberg, DeWitt Wallace Professor of History at Macalester College, St. Paul, Minnesota. Professor Rosenberg was originally one of the collaborators on the first edition of this book and wrote significant parts of the text. We appreciate Professor Rosenberg’s contributions and his generous decision to allow us to use them in both editions of the book.

Paul R. Joseph was Professor of Law at Shepard Broad Law Center, Nova Southeastern University, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Professor Joseph tragically died in 2003. Professor Joseph was one of the original collaborators on this book, but he had to withdraw because of other commitments. Professor Joseph wrote part of the chapter on the criminal justice system, and we are most grateful that he allowed us to use it in this book. We also acknowledge the contribution to Chapter 1 of Professor Joyce Penn Moser of Stanford University. Professor Moser planned to collaborate on the second edition of this book but was unable to do so.

We have discussed the material in this book with far too many people to name here, but we always benefited greatly from their insights. We would especially like to thank the users of the first edition of the book for their wonderful suggestions, including David Fisher, Kirk Junker, Scott Mulligan, Gary Peter, and Debbie Shapiro. If only we could have embraced all of their suggestions! We also gratefully ← ix | x → acknowledge the assistance of Richard Abel, Dyanne Asimow, Stuart Banner, Paul Bergman, Samantha Black, Ray Browne, Drew Casper, Kimberle Crenshaw, John Denver, Steve Derian, Sharon Dolovich, Jennifer Factor, Sam Feldman, Steve Greenfield, Gillian Lester, Stefan Machura, Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Francis Nevins, Guy Osborn, Peter Robson, Charles Rosenberg, William Rubenstein, Gary Schwartz, Andrew Schepard, David Schultz, Brad Sears, Louis Schiff, Rafael Simon, Rob Waring, Dan Watanabe, and Steven Yeazell.

Lastly, we would like to thank the students in Asimow’s seminars on Law and Popular Culture at UCLA Law School and at Stanford Law School. They inspired us to believe that it made sense to write a course book for a course that didn’t yet exist. Many of their ideas and comments found their way into the first and second editions of this book.

Of course, we bear the responsibility for any errors or omissions.

| xi →

We’re in a segregated Alabama courtroom in the mid-1930s. The packed room is hushed as Atticus Finch rises to begin his closing argument to the jury in the case of Tom Robinson. Robinson, a young black man, is falsely accused of raping a white woman. The film is To Kill a Mockingbird (1962).

Two white eyewitnesses (the alleged victim and her father) have testified against Tom Robinson. The jury is all male and all white. Finch’s closing is brave and eloquent. He says: “In our courts all men are created equal. I’m no idealist to believe firmly in the integrity of our courts and our jury system. That’s no ideal to me. That is a living, working reality.” But the case is hopeless. The jury quickly convicts Tom Robinson. Soon he is dead, supposedly shot while trying to escape.

With his stirring but futile defense of Tom Robinson, Atticus Finch became the patron saint of lawyers. The heroic character of Atticus Finch inspired countless young people to become lawyers. It has the same power to inspire them today.

Now we’re in a different courtroom. It’s in Boston and the time is the 1980s. The film is The Verdict (1982). Frank Galvin staggers to his feet to deliver his closing argument. Galvin’s client, Deborah Ann Kaye, went into the hospital to give birth. Something terrible happened during anesthesia and she is in a permanent vegetative state. Galvin is a hopeless alcoholic, a loser who ignored the case almost until the trial began. His opponent, Ed Concannon, is a big firm partner who represents ← xi | xii → the Archdiocese of Boston, which operated the hospital. Concannon has played every dirty trick in the book to defeat Galvin. The judge seems to be in Concannon’s pocket. Galvin’s closing argument ignores the facts of the case and urges the jury to do justice. The jury returns with a stunning verdict for the plaintiff. We leave the theater with the satisfied feeling that justice was done, but the film paints a dark picture of the character and ethics of the two lawyers. Few would be inspired to take up the legal profession after seeing this film.

This book is designed to be used as the reader for a course in law and popular culture. The course studies movies like To Kill a Mockingbird (Chapter 3), The Verdict (Chapter 4), and many other films and television shows. The course on law and popular culture originated as a law school offering, but the model works well in a wide range of undergraduate or graduate programs. The first edition of this book was used in programs as diverse as American studies, criminal justice, mass media, and film and television studies, and within such traditional departments as history, political science, or sociology.

The course on law and pop culture explores the interface between two subjects of enormous importance to the lives of everyone—law and popular culture. Why should we care about the interaction of these subjects?

Law pervades modern society. Increasingly, courts decide some of the most fundamental social and economic problems of society, including such hot-button issues as abortion, the death penalty, the right of privacy, gun control, homosexual marriage, affirmative action, or federal health care legislation. Indeed, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that George W. Bush rather than Al Gore won the 2000 election (Bush v. Gore, 2000).

So many aspects of our lives are profoundly affected by laws, police, judges, and lawyers. We want the police and the courts to catch and convict criminals to keep us safe, but we want our privacy to be protected and the rights of the accused to be safeguarded. We want our legal system to deliver justice, but sometimes it fails to do so. What do we mean by “justice” and why can’t the legal system deliver it? Lawyers are among the most despised of all professions. Why is this? Is it justified? What do lawyers actually do, anyway? Everyone needs to know much more about law, lawyers, and the legal system than they do now.

Popular culture is even more pervasive than law. All of us swim in a sea of films, television shows, books, songs, advertisements, and numerous other imaginative texts. The average family watches about five hours of television each day, not counting time spent watching TV content on mobile devices. During thirty minutes of watching television, we consume more images than a member of pre-industrial society would have consumed in a lifetime. Everyone needs to know ← xii | xiii → much more than they do about popular culture in order to understand, interpret, and fight back against the onslaught of images that assault us every day.

The course in law and popular culture is intended to deepen students’ understanding of both law and popular culture and the many ways in which they influence each other. The wall between law and popular culture allows a lot of traffic to pass in both directions. In particular, we believe that popular culture both reflects and constructs our perceptions of the law. It can also change the way that the players in the legal system behave.

In addition to considering questions about law and lawyers, this course focuses on filmmaking, film history, and film theory. As we watch these legally themed movies or TV shows, what can we learn about writing, directing, editing, or scoring? How are these narratives constructed? What’s the filmmaker’s hidden agenda? What makes a pop culture product seem “realistic”? What genre do these films fall into, and do they respect the rules of that genre? How did the business practices of the industry or the cultural trends of the time influence the production and reception of the film or TV show?

We do not assume that instructors in law and pop culture have any training (formal or otherwise) in law, filmmaking, film theory, history, or in any other discipline. The book is written in plain English, without theoretical jargon, and it can be taught by anyone who enjoys popular culture and is interested in law. The materials treat each movie or TV show as both a cultural and as a legal text as well as a work of art and a product manufactured to entertain a mass audience and make a profit. Our job is to supply the materials to make the course work, no matter what the background of the person who is teaching it.

Each chapter in this book (except the introduction) is based on a particular film or television show involving law and lawyers. The book deals with many issues of criminal and civil justice and with problems of law practice and legal ethics. It discusses how the lawyers in the film or TV show are represented. It tackles such institutions as law school, the jury, big law firms, and the economics of law practice. And it addresses all of these issues and institutions in a critical and challenging way.

When students are brought face-to-face with popular culture, the result is different from the typical college-level course. Normally, the teacher is the expert, and the students passively soak up as much of the teacher’s knowledge as they can absorb. But in a course based in the media of popular culture, the students share expertise with the instructor. Every student in the room is already an expert in interpreting popular culture. They know the language of film and television. They have been practicing that language since before they learned to talk, much less read. Every student has seen hundreds of movies, thousands of hours of television shows (not ← xiii | xiv → to mention their exposure to music or the Internet). In many cases, the students have consumed far more popular culture than the instructor has (Denvir 1996).

The result is electrifying. The students bring with them deeply felt opinions about pop culture. They are moved and inspired, or infuriated, by films like To Kill a Mockingbird, Anatomy of a Murder, The Verdict, or Philadelphia. They are full of ideas, arguments, and interpretations. They speak up in class. They argue with each other and with the instructor. They are not overawed by the instructor’s interpretation of a film because their interpretation may be just as valid. The level of interactivity in the classroom equals that in the most engaging and best-taught classes.

Appropriately to the world of film and television, this preface is an ill-disguised pitch. It’s pitched to the people who decide what courses they want to teach and what books to assign for those courses. We hope that a course based on these materials will be fun to take and to teach. But it’s not all fun and games and it certainly isn’t fluff. As we said, the twin subjects of law and popular culture are two of the most meaningful in the lives of our students. Students deserve and will benefit from a critical and serious examination of these subjects and the many ways they interface with each other.

We wish to all students and teachers of law and popular culture an enjoyable and stimulating tour through these two vitally important and constantly intersecting worlds.

Michael Asimow &

Shannon Mader

| 1 →

Law, Lawyers, and the Legal System

| 3 →

1.01 What this book is about

This book is meant as the reader for a course with the general theme of “Law and Popular Culture.”1 It is suitable for undergraduate and graduate classes or seminars in American studies, criminal justice, political science, film studies or other academic programs, as well as in law schools. Therefore, it provides material on the study of popular culture that may be unfamiliar to most law students, as well as material on law, lawyers, and the legal system that may be unfamiliar to most non-law students. Each chapter, with the exception of this introduction, consists of readings based on a particular film or television show that students should view before class discussion begins. (In some classes, the films are viewed outside of class; in others, they are viewed at the beginning of the class.) Individual instructors, of course, can substitute different films or readings for those suggested.

1.02 Definitions of “popular culture” and “popular legal culture”

This book frequently uses the words “popular culture” and “popular legal culture.” What do we mean by these vague terms? ← 3 | 4 →

1.02.1 The double meaning of “popular culture” and “popular legal culture”

We use the terms popular culture (often shortened to “pop culture”) and popular legal culture in this book in two distinct ways (see Friedman 1989). These might be called the “broad” and “narrow” meanings of these words.

According to the “broad” approach, the term “popular culture” means all of the knowledge, behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes possessed by people in a particular society or subgroup of that society. Using a similar broad meaning, popular legal culture refers to everything people know or think they know about law, lawyers, and the legal system. We frequently have the broad meaning in mind when we use the term “popular culture.” For example, we sometimes hear that America has a “culture of violence,” meaning that there are many people who behave violently in America. As another example, the U.S. Supreme Court said that Miranda warnings have become “part of our national culture” (see ¶1.05.1). The Court might have used the words “popular legal culture” instead of “national culture,” because it was referring to what everybody knows (or thinks they know) about the warnings that police must give suspects after they are arrested.

The “narrow” approach is quite different. Under the “narrow” approach, “popular culture” means media products (whether in the form of films, television, print publications, music downloads, stage plays, and so on) that are manufactured and marketed for popular consumption. We use this narrow definition when we say that people consume a lot of pop culture, meaning that they watch a lot of television or movies. Again using the narrow approach, “popular legal culture” means media products about law, lawyers, or the legal system.

1.02.2 Popular culture and high culture

There is a well-understood distinction between “popular culture” and “high culture.” Popular culture (using the narrow approach set out in ¶1.02.1) covers commercially produced works intended for the entertainment of mass audiences. Pop culture producers assume that consumers will enjoy and quickly forget these works. In contrast, “high culture” refers to works that are produced and marketed for consumption by elite rather than popular audiences. For example, high culture incorporates classical music and opera, paintings and other works of visual art, poetry, or serious fiction—usually older fiction that has succeeded in being recognized as literature. Works of high culture are intended to have lasting rather than merely transitory value. Generally, the production of works of high culture is less collaborative ← 4 | 5 → and commercial than the production of works of popular culture. However, many works that were originally produced as mass entertainment are later promoted to high culture status such as the novels of Charles Dickens or Mark Twain, the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, or the plays of Shakespeare. Perhaps detective stories by Arthur Conan Doyle and Raymond Chandler have also made the leap into the sort of high culture studied in serious literature classes.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 357

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433113246

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453910801

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781453942017

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781453942024

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1080-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2004 (August)

- Keywords

- USA Film Recht (Motiv) film television show cultural text

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG