Hip-Hop and Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

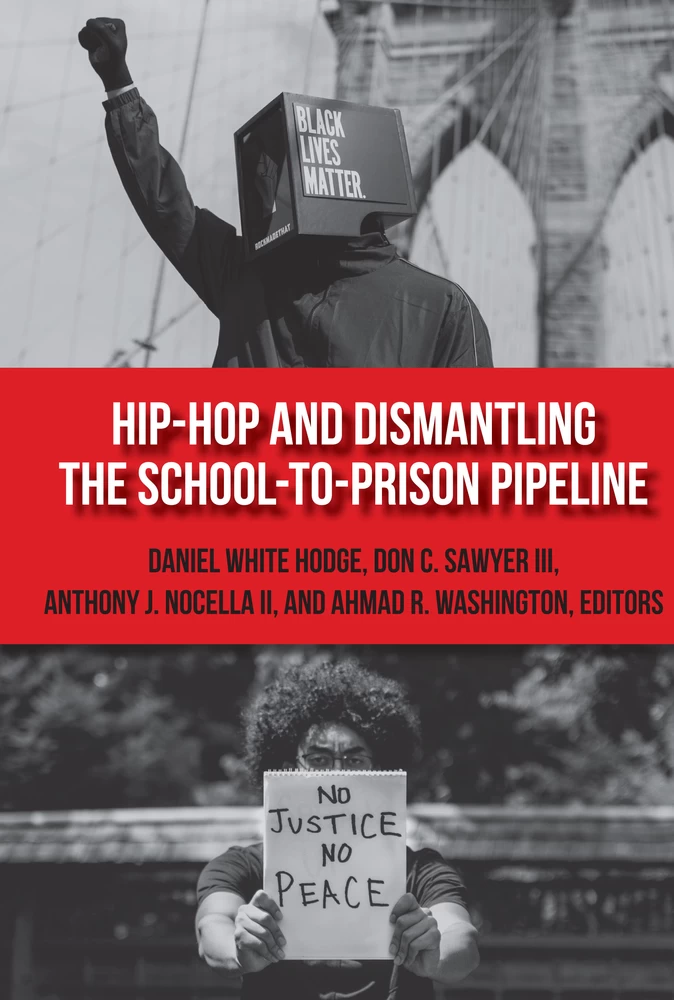

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword (H.A. Jabar Odokhan-El)

- Introduction. Hip Hop, the School-to-Prison Pipeline, and #Noyouthinprison (Daniel White Hodge, Don C. Sawyer III, Anthony J. Nocella II, and Ahmad R. Washington)

- PART I. Hip Hop and Cultural Imperialism in School

- Chapter One. Hip Hop in the Time of Trauma (Valeria Benabdallah)

- Chapter Two. The New Eugenics: Challenging Urban Education and Special Education and the Promise of Hip Hop Pedagogy (Anthony J. Nocella II and Kim Socha)

- PART II. Hip Hop and Juvenile Injustice System

- Chapter Three. They Schools: Hip Hop as a Pedagogical Process for Youth in Juvenile Detention Centers (Travis Harris and Daniel White Hodge)

- Chapter Four. Hip Hop, Food Justice, and Environmental Justice (Anthony J. Nocella II, Priya Parmar, Don C. Sawyer III, and Michael Cermak)

- PART III. Hip Hop Activism on the Streets and Alternatives

- Chapter Five. Contesting the School-to-Prison Pipeline Through Political Rap Music: An Interview with Skipp Coon (Ahmad Washington)

- Chapter Six. Transforming Justice and Hip Hop Activism in Action (Anthony J. Nocella II)

- Chapter Seven. Soulja’s Story: Critical Mentoring as a Site for Street Activism (Torie Weiston-Serdan and Arash Daneshzadeh)

- Contributors

- Index

Foreword

H.A. Jabar Odokhan-El

Through great pressure, pain, and stress—the greatest of objects are produced! Diamond, gems, crystals, and numerous metals are natural materials that have to be dug deeply (mined from the earth). They are then cleaned, polished, and put to use in a variety of ways. Some are used simply for symbolic display, such as diamonds, while others serve to facilitate high technical procedures, such as coltan in cell phones.

It is from the same great pressure of the natural world that we live in that musical genres such as the blues, jazz, and hip-hop culture have come to life; and YES, I said culture, and not just “music”. Hip-hop is more than just music, “beats and rhymes”. Hip-hop is a cultural and social phenomenon!

Popular hip-hop artist Drizzy Drake, in his 2013 hit song “Started from the Bottom” said, “Started from the bottom now we’re here, Started from the bottom now the whole team here” (Aubrey Graham, Noah Shebib, Michael Coleman, 2012). Hip-hop music started from the bottom and now it’s here, still in existence and at the very top of the music industry—globally! It was created in one of the most amazing, treacherous, and worldly known cities, New York City. Hip-hop was created by the group (or race of people) that are considered the lowest class, the least respected, and have the least material resources. Hip-hop was used (like medicine) to remedy the ills of a racist and oppressive society, to help to create a feeling of joy; opposite to the anxiety, pain and stress endured as a Black person in America.

←xiii | xiv→As it was then, so it is now. Hip-Hop and Dismantling the School to Prison Pipeline, details the method of how to apply the medicine of hip-hop to society; how to overcome the many sicknesses bred within from being built on the foundation of injustice, slavery, murder, and exploitation. Editors Daniel White Hodge, Don C. Sawyer III, Anthony J. Nocella II, and Ahmad R. Washington have not provided us with medicine in cream, pill, or liquid form. Instead, they gave us healing in the form of “the word”; and “man” does hip-hop know about the use of words!

For example in the 1980s, a young Black man in New York city (just a generation or two from slavery’s end) said to himself while enduring through the struggle of life, “It’s like a jungle sometimes. It makes me wonder how I keep from goin’ under (Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, 1982)”.

After saying that to himself a few times, he then wrote it on paper. Later the whole world danced and sang along with him as they listened to the 1982 hit song, The Message by Grandmaster Flash.

This is just one example, showing and proving that hip-hop is a cultural phenomenon. It’s a brilliant use of “word play”; metaphors, similes, and comparative descriptive language is nothing short of masterful and the whole world knows it. From its rugged and gritty beginning in a city where it’s “survival of the fittest”, hip-hop developed and grew from just having a good time and self-expression to generating billions worldwide annually. LL. Cool J. in his song ‘I’m bad’, said, “No rapper can rap quite like I can I’ll take a musclebound man and put his face in the sand” (L.L. Cool J, 1987, Track 1).

It started with a culture or elements that made up a culture. MC’ing or rapping is the most well known, but don’t leave out DJ’ing (turntablism), breakdancing (B-Boying), its fashion of dress, the language and slang it used, or graffiti art. On May 16, 2001, Hip-hop was recognized as a world culture by the United Nations when The Hip Hop Declaration of Peace was accepted by UNESCO.

So who are the people that started this cultural phenomenon “rap”, better known as hip-hop music or hip-hop culture? Well, simply put they are the descendants of enslaved Africans (Afro-Asiatics) that were brought to America by European invaders and colonizers. They are the descendants of the people that survived what is called the Trans-Atlantic slave trade or the Maafa (The Great Disaster). The same people that were not allowed to read (by law) for over 300 years, which brings us to the school to prison pipeline, which I work against professionally.

Hip-Hop and Dismantling the School to Prison Pipeline is like a guide, or a roadmap, or a reference book on how to “use” hip-hop as an educational tool—for healing, for empowering activists and organizers, for changing society and the world we live in. This collective of authors is a testament to the treasure trove of amazing work done at the grassroots level all over the country. It promises us, like a small germ (hip-hop in the Bronx) there is the ability to grow large.

←xiv | xv→There are grassroots organizations changing lives every day, like Black Men Rising in New Orleans who mentor youth, as well as counsel and train incarcerated juveniles, or the West Dayton Youth Task Force that got the curriculum changed in Dayton public schools and books added by Booker T. Washington and Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

There are grassroots organizations effecting statewide outcomes like Racial Justice NOW! who successfully led the campaign to end out of school suspensions for pre-school—3rd grade for the whole state of Ohio. There are also national grassroots initiatives like Save the Kids who have blazed a path (that can be multiplied and duplicated) using hip-hop activism and transformative justice to put an end to the school-to-prison pipeline.

If and when the nurses and doctors, also known as community members, decide to treat the ills of society—they must include in their medicine bag Hip-Hop and Dismantling the School to Prison Pipeline by editors Daniel White Hodge, Don C. Sawyer III, Anthony J. Nocella II, and Ahmad R. Washington.

REFERENCES

Aubrey Graham, Noah Shebib, & Michael Coleman. (2012). Started from the Bottom. On Nothing Was the Same [Digital Download]. New York, NY: OVO, Aspire, Young Money, Cash Money, Republic.

Chase J., Fletcher E., Glover M., & Robinson S. (1982). The Message [Record] New York, NY: Sugar Hill Records.

L.L. Cool J. (1987). I’m Bad. On Bigger and Deffer [Cassette]. New York City, NY: Def Jam Recordings.

←xv | xvi→

Introduction

Hip hop, the School-to-Prison Pipeline, and #NoYouthInPrison

DANIEL WHITE HODGE, DON C. SAWYER III, ANTHONY J. NOCELLA II, AND AHMAD R. WASHINGTON

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 148

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433174391

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433174414

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433174421

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433174438

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433174407

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16185

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (November)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XVI, 148 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG