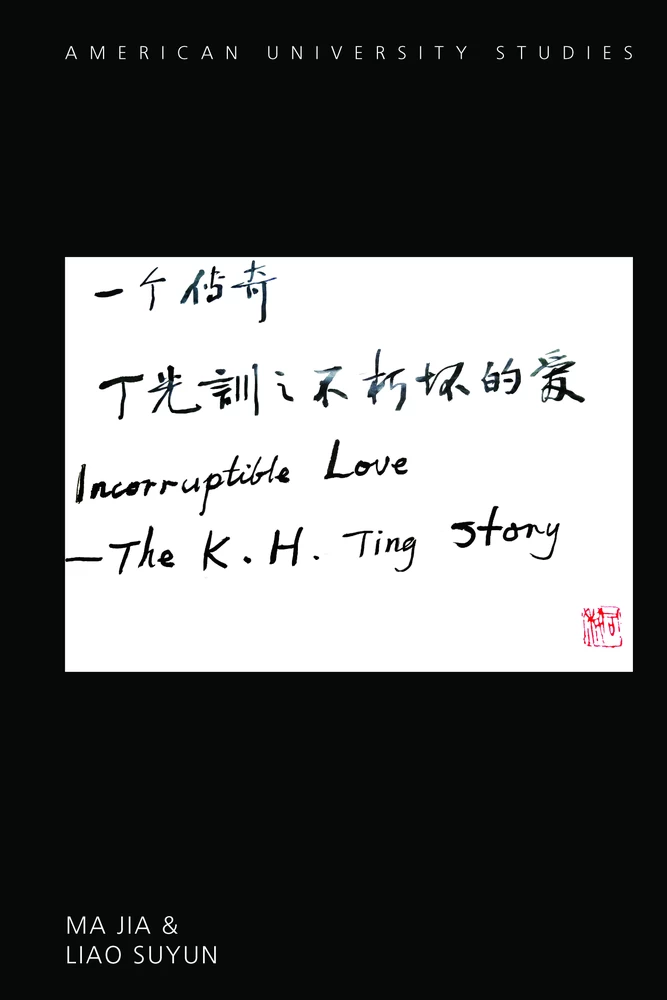

Incorruptible Love

The K. H. Ting Story

Summary

K. H. Ting became the principal of Jinling Theological Seminary in 1952 and remained in this position until his death, making him the longest-standing principal of any theological seminary in the world. He experienced many difficult times in his 97 years, and in any ways the history of Christianity in China is reflected through the ups and downs he experienced. In Incorruptible Love: The Story of K. H. Ting, the authors offer Christians, as well as people of other spiritual beliefs, intellectuals, and the general public, a greater understanding of K. H. Ting’s life and beliefs. This biography will help people learn not only about K. H. Ting, but also about the fundamentals of Chinese Christianity.

Written in a blend of creative and academic writing styles, Incorruptible Love makes the story of K. H. Ting vivid and convincing. This text can be used in courses on Christianity in China, the Chinese Church, religion in China, and modern Chinese history.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. The Wind Blows When It Chooses

- Part 1: Where the Story Begins: Interviews with K. H. Ting

- Part 2: An Upright Man’s Compassion: Rejoicing in Truth

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 2. New Legend of a Good Christian—K. H. Ting’s Early Life and Career in Shanghai

- Part 1: Life at St. John’s University: Development of Spiritual Beliefs

- Part 2: Assuming Elijah’s Mantle: Work Experience After Graduation

- Part 3: Stronger than David’s Lyre: Influence of a Courageous Churchman

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 3. Discerning Truth through a Long Journey Abroad

- Part 1: Toronto: Signs of Leadership

- Part 2: New York: Development of Theological and Personal Ideals

- Part 3: Geneva: Preparations for Returning to China

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 4. At the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary (NJUTS): 1952–1965

- Part 1: An Emerging Leader

- Part 2: Seeking Christian Common Ground

- Part 3: Moving Forward with Caution

- Part 4: Struggling under Job’s Question

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 5. Looking Back: The Time of GCR

- Part 1: Who Protected K. H. Ting?

- Part 2: Together, Though Far Apart

- Part 3: No Longer Strangers to Revolution

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 6. At the Nanjing Union Theological Seminary (NJUTS): After 1980

- Part 1: Return to No. 17: Events Before and After the School’s Reopening

- Part 2: Saturday Lectures: The Teaching Method of K. H. Ting

- Part 3: Attention to Warmth and Love: Ting’s Management System

- Part 4: Carrying Back the Olive Branch: NJUTS’ Students Study Abroad

- Part 5: Peace of Mind in the Face of Disaster: Three Challenges for K. H. Ting

- Part 6: New Wine in a New Bottle: Beginning Again

- Part 7: Looking Towards the Future: The New NJUTS

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 7. As Diplomat and Spokesperson for Christianity in China

- Part 1: The Ladder to Heaven

- Part 2: On the International Stage

- Part 3: Always a Pleasure to Greet Friends from Afar

- Part 4: Christianity and Other Religions in China

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 8. The Amity Foundation

- Part 1: A Foundation without Funds?

- Part 2: “A Real Hermit Living in the Bustling Place”: The Special Location of the Amity

- Part 3: The Story of “Amity Bakery”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 9. A Theologian Who Follows St. Paul

- Part 1: How to Understand the “Three-Self” Movement?

- Part 2: Who Said It’s Simply Two Sides of a Coin?

- Part 3: Modernist and Fundamentalist Christianity in China

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 10. A Theologian Who “Writes How I Want to Write”

- Part 1: The Role of “Cultural Christians”

- Part 2: Publications about Christianity and K. H. Ting’s Own Writings

- Part 3: Treasure in Clay Jars: Theological Reconstruction in China

- Part 4: Providing Only Key Points: K. H. Ting’s Theological Method

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 11. Life and Family

- Part 1: K. H. Ting’s Family: An Intellectual Family Tradition

- Part 2: K. H. Ting’s Wife, Kuo Siu May

- Part 3: K. H. Ting Stated: “I need time to relax!”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 12. Love Never Ends

- Part 1: My Impression of K. H. Ting: A Philosopher and A Poet

- Part 2: Uncompromised Love

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Afterword

- Appendices

- 1. A Brief Chronology of K. H. Ting’s Life

- 2. Glossary of Terms in English and Chinese

- 3. Glossary of Chinese and English Names in the Text

- Index

THE WIND BLOWS WHEN IT CHOOSES

Part 1: Where the Story Begins: Interviews with K. H. Ting

The common Chinese idiom, “The waterfront pavilion gets the moonlight first”, can be applied here to describe how Ma Jia1 built up a friendship with the Bishop K. H. Ting. More than 20 years ago in 1994, Ma Jia was a lecturer at Nanjing University, one of the most recognized universities in China. As an active Ph.D. scholar, Ma Jia also taught a survey course about Chinese literature at Nanjing Union Theological Seminary (NJUTS), China’s most prestigious seminary. Ma Jia soon realized that the president of NJUTS, K. H. Ting, just happened to also be the vice-president of Nanjing University. Ma Jia and K. H. Ting also shared a common friend, Professor Wang Weifan,2 the Academic Dean of NJUTS. While familiar with Ma Jia, Wang Weifan was also K. H. Ting’s colleague and old friend; Wang described their friendship and partnership as one that “waxed and waned but endured over fifty years.”3

On one occasion, Ma Jia inadvertently expressed to Professor Wang the difficulties of publishing his doctoral dissertation that explored Christian cultural influence on modern Chinese literature. Wang Weifan had been a well-recognized scholar in the field of Christian culture in China, as well as an expert on Chinese literature. During the 1940s, Wang studied Chinese ← 1 | 2 → literature at National Central University, which led to a desire to explore the relationship between Christianity and Chinese culture as well as literature. Weifan was always enthusiastic to help others as he was a pious Christian and, after hearing about Ma Jia’s situation, introduced Ma Jia to Bishop Ting and offered academic as well as financial support. Soon after Wang Weifan sent Ma Jia’s dissertation to K. H. Ting, Jia received a cordial response from the bishop that read: “I read your fascinating thesis in the hospital. For me it is a completely new research area. I feel this field can be explored deeply and comprehensively, and hope there would be more scholars get involved.”4

In the early 1990s scholars in the world of Chinese academia were reluctant to conduct research on sensitive areas including the history of Christianity, Christian culture, theology and other related topics, while almost no press would publish such works.5 Fortunately, after several failures, Ma Jia finally found an academic press in Shanghai that would publish his dissertation, under the condition that a certain sum of money would be contributed to the publisher to cover printing costs. The amount of money was not enormous but still substantial for Ma Jia, who had just begun to lecture at Nanjing University less than two years previously. Fortunately, K. H. Ting provided Ma Jia monetary aid from his “Bishop Compensation”, while Professor Wang and staff from the Amity Foundation’s Hong Kong office also raised funds. With such financial assistance, Ma Jia’s book was finally published at the end of 1995.

On Christmas Day of 1995, shortly after his first book was published, Ma Jia visited Bishop K. H. Ting at the bishop’s residence for the first time. The bishop’s home was located on 378 Mouchou Road, a two-story Western-style house on a bustling street near the downtown core of Nanjing, whose former resident was a Christian missionary before the liberation.6 Surrounded by a high brick wall and dense trees, the house made Ma Jia feel warm and peaceful when he stepped in.

St. Paul’s Church, an ancient Gothic cathedral with mottled walls, was located nearby, to the north of the house; its walls seemed to hold history and emanated a mysterious sense of the West. Across from Hanzhong Road to the north, NJUTS stood not far from the church. This seminary, with its 48 years of history, was located at 17 Da Jianyin Lane.7

17 Da Jianyin Lane was once the location of Jinling Women’s Theological Seminary. At the end of the 1940s, Jinling Theological Seminary, which was a key part of NJUTS, occupied the majority of the area across from Shanghai Road. Unfortunately, after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China ← 2 | 3 → (PRC),8 this area was eventually re-allocated to Nanjing Medical University. The main building of Jinling Theological Seminary, now preserved as a historical site, still remains on the campus of the medical university. As many Chinese people like to say when facing irresistible historical phenomena, circumstances change with the passage of time; NJUTS may never have the chance to return to its original site because of the complicated political and economic situation in China. Today we can only imagine the scene of the 1940s, when St. Paul’s Cathedral lay to the north while the dormitory of faculty and students of Jinling Theological Seminary lay to the south. These two buildings bordered the campuses of Jinling Theological Seminary and Jinling Women’s Theological Seminary, with these places eventually forming a Christian village.

But the past is past. History can change everything.

Now the inhabitant of the house behind the wall of 378 Mouchou Road with whom Ma Jia was meeting was K. H. Ting.9 At that time, K. H. Ting was president of NJUTS, the Bishop of the Anglican Church, honorable president of CCC,10 honorable chairperson of TSPM11 and vice-chairperson of Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). With the exception of a few years of absence during the GCR,12 K. H. Ting had been living in this house since 1952; K. H. Ting and the house itself can be seen as historical records of Christianity in China since the 1950s, if not the foremost symbols of all Christianity in China.

Ma Jia still remembers the excitement he felt when, during that first meeting, he received the bishop’s calligraphy to use as the title of his book about the relationship between Christian culture and modern Chinese literature. After that first meeting, Ma Jia had other chances to meet with the bishop in the Mouchou Road house and was always impressed by K. H. Ting’s profound knowledge, great insight, surprising modesty and open-mindedness. In 1998, he began his research for this biography and since then has taught in universities in Europe and North America. While travelling and working abroad, he met different churchgoers and scholars of Christianity interested in K. H. Ting. Such people described and imagined the bishop in many different ways, but no one he met could provide a complete picture of K. H. Ting, which gave Ma Jia the idea of writing a biography of Bishop K. H. Ting so as for more people, inside and outside of the Church, to learn about the bishop. However, K. H. Ting did not like to talk about himself and only agreed to be interviewed when convinced by Ma Jia that his biography would inform more people, particularly people outside of China, about the reality of Chinese Christianity. ← 3 | 4 →

Time flew and it was not until December 23, 2000, that Ma Jia started to interview Bishop K. H. Ting.

Ma Jia can still remember how it was a typical winter afternoon when he arrived outside of 378 Mouchou Road, ten minutes ahead of the scheduled interview. The dispersed sunshine spreading through the clouds made the cold weather feel a little bit warmer. While waiting, Jia noticed that the street was not crowded, but the non-stop noises from vehicles and bicycles still reminded him of the bustle of the city. Spurred by the cold wind, pedestrians and bicycle riders passing by in haste, oblivious of Ma Jia’s existence, it was a moment that combined a secular scene with a sacred spirit.

The ten minutes passed quickly before Ma Jia approached the door of the garden wall and pushed the doorbell. Immediately, the security guard opened the door and led him into the bishop’s study on the second floor, where he received a warm welcome from K. H. who, after an exchange of greetings, started to speak in Mandarin with his Shanghai accent.

Shanghai and Nanjing are the two hometowns in K. H. Ting’s life. Ting was born in Shanghai in 1915 and spent his childhood and youth there until 1946. Shortly after Ting returned from Europe in 1952, he started to live in Nanjing and remained here until his death. Interestingly, as Shanghai and Nanjing developed into two cosmopolitan cities in China since the early 20th century, both played an important role in the history of modern Chinese Christianity. Since the implementation of the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, Protestant Christianity began to establish Nanjing as the missionary center in south-eastern China. Christian missionaries built churches, established seminaries and Christian colleges in Nanjing, such as St. Paul’s Cathedral, Jinling Theological Seminary and Jinling Women’s Theological Seminary, the Private University of Nanking and Ginling College (Jinling Women’s College). Meanwhile, in Shanghai, Christian missionaries, particularly those from America, extended their influence by establishing Christian-based facilities including St. John’s University and YMCA Shanghai, some of which became highly important in shaping education, culture, economics and politics in the modern Chinese society.

Ma Jia interviewed Bishop K. H. Ting ten times face-to-face and conducted some short phone interviews between the winter of 2000 and 2006. During this time China was developing dramatically both politically and economically, while there was also a sizable change in Chinese Christianity and the research field of Christianity in China. The total number of Protestant Christians and new churches built in China increased, while there were more theological institutes than ever before, with theological education also improving, ← 4 | 5 → with studies of Christianity in China being produced both inside and outside of the Church. The basic model of the national Chinese Church was built and the voice of Chinese Christianity sounded special and attractive in the realm of global Christianity. Meanwhile, after six years of work, the national movement of Theological Reconstruction in Chinese Christianity, led by Bishop K. H. Ting, was showing distinct positive signs. Since 2006, Ma Jia had kept contact with the bishop and took the opportunity to visit him when he delivered lectures at Nanjing University, his Alma Mater, or went to see friends and relatives there. However, after 2006, K. H. Ting’s health declined year by year, which meant the locations where they met changed, from the bishop’s home to the hotel and eventually the hospital. While his conversations with the bishop were no longer as substantial as before, Ma Jia was simply happy to be with the bishop, or have lunch with his family members.

K. H. Ting’s thoughts remained youthful despite his declining health. On August 6th, 2004, at the age of eighty-nine, Bishop Ting gave a speech at the Church Bible Ministry Exhibition in Hong Kong. The bishop informed the world of Christianity’s presence in China and his certainty that the religion would continue progressing so as to become larger and stronger. The bishop cited the reason for the religion’s rise as people were now free to be religious believers in China.13 While there are still obstacles to and unfair treatments of Christians and other religious believers in China, freedom of religion established under the Chinese Constitution has better the situation for these groups compared to the past.

Part 2: An Upright Man’s Compassion: Rejoicing in Truth

Softly I am leaving,

Just as softly as I came;

I softly wave goodbye

To the clouds in the western sky

.……

Quietly I am leaving,

Just as quietly as I came;

Gently waving my sleeve,

I am not taking away a single cloud.14

In 1928, Xu Zhimo, emerging as one of the most renowned Chinese poets of this period, wrote arguably his most famous poem Taking Leave Cambridge ← 5 | 6 → Again when he revisited the Cambridge campus in England. Zhimo died in a plane crash in south-east China three years later and the beautiful rhymes, together with the sorrowful emotion and poet’s unexpected sudden death, made the poem popular ever since, with readers constantly immersing themselves in the unique feeling of Xu’s romantic love stories and tragic end.

Time passed by. In 1982, Bishop K. H. Ting took a Chinese Church delegation to visit the United Kingdom where they would first attend 10 Downing Street and meet the former British Prime Minister Lady Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013), as well as the Archbishop of Canterbury in Lambeth Palace, located near the University of Cambridge. On November 22, 2012, 30 years after his first official visit to the Anglican Church as the president of China Christian Council (CCC) and Anglican Bishop, K. H. Ting passed away peacefully at Jiangsu Provincial People’s Hospital in Nanjing, with his body cremated on November 27. Ma Jia wrote an email to Stephen Ting, the elder son of K. H. Ting, to express his condolences and received this reply: “My father left very peacefully, as if asleep. I was next to him as he was being called in. He lived a long, full life, and I am truly thankful for the many years I had with him and also for the time I have with friends like you.”

People may wonder if there are any similarities between a well-known romantic Chinese poet and an important Christian leader and theologian in modern China. The answer is yes, as they shared the same values in at least two aspects of life: the incorruptible love of people and their country

Almost 17 years ago, Ma Jia published an article about Xu Zhimo’s poems, “The Lingering Religious Mood of Xu Zhimo’s Poems”,15 where Jia explored the interconnection between the religious mood in Xu’s poems and his life, thought and spirit. As Xu said:

Whether there is only one god or there exist many gods or no gods, the only standard of a poet to feel the existence or non-existence of gods comes from his/her poetic expression. The obvious conflicts from the viewpoint of ordinary people may become harmonious parts from the eyes of a poet, because a poet can grasp the truth through literal meanings.16

Based on what Xu said above, we can conclude that he always understood religion from the aspect of a poet, meaning that while his personal characteristics such as yearning for freedom and lack of endorsement for religious ceremony were far from the practices of a religious believer, he held a deep belief in the two very basic religious principles, love and kindness. Xu Zhimo’s friend, the famous scholar and politician, Hu Shi confirmed such when saying the following while praising the poet: “His whole life is the symbol of love. Love is his religion as well as his God.”17 ← 6 | 7 →

As a Christian and important Chinese Church leader, love played an irreplaceable role in K. H. Ting’s life. For believers and non-believers this kind of love resembles a mother’s first kiss to her baby, the greeting from Christ or a bridge connecting heaven and earth. It is not only conveyed to disciples, friends, and colleagues, but also spread to every corner of the world. This kind of love solved the imbroglios within different churches, among different believers and strengthened the relationship between believers and non-believers. It is the nature of God, as confirmed by the bishop himself:

What is the most important and most fundamental attribute of God? It is God’s love, the love shown in Christ, the love which does not hesitate before suffering or the cross, the love which made him give up his life for his friends. The justice of God is also God’s love. If love spreads throughout humankind, it becomes justice. This is love entering into the world. Love does not come to destroy, but to sustain, heal, teach, redeem and give life.18

Interestingly, as an undergraduate student at St. John’s University from 1932 to 1937, K. H. Ting majored in English and immersed himself into English literature and culture. In his long career as a pastor and then Anglican Bishop, K. H. delivered numerous beautiful sermons in China and abroad which featured poetry from the Bible and other literary resources. Here it is a quotation from one of K. H. Ting’s speeches:

… Paul said: “(love) does not rejoice in wrongdoing, but rejoice in the truth” (1 Cor. 13:6). Love and hate are a pair of opposites. Without hate there can be no love. Where there is love, there is certainly hate. To rejoice in truth is surely to oppose falsehood; to oppose injustice is surely to uphold justice. It is worth repeating Diderot’s words to artists: “It should be the intention of every upright man who plies a pen, a paintbrush, or a sculptor’s knife to make love more loveable, evil more despicable, and the bizarre more noticeable.” I think that all of us who witness to the Lord with Bible in hand should also be included among their ranks.19

As we know, K. H. Ting grew up in a Christian family in Shanghai and his parents influenced him strongly. The influence of the bishop’s mother was particularly important to him, emotionally and spiritually; she was a pious Christian and her father had been a pastor in St. Peter’s Church. K. H. was held in his mother’s arms when baptized at four months old while her influence was still present when he changed his major from civil engineering to English literature, or sought a degree in divinity.

Ting’s father died of cancer at 80 while his mother lived longer, ultimately passing away at the age of 101. Prior to her death, she lived in the old residence ← 7 | 8 → on Hengshan Road in Shanghai, with K. H. Ting’s elder sister. His mother and her love, indispensable to his life and career, had accompanied him throughout life and the bishop therefore felt that his mother’s passing in 1986 was “the most important thing during [his] lifetime”. He wrote movingly:

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 302

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433139116

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433139123

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433139130

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433139147

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4331-3912-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (October)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. VIII, 302 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG