The Cinema of Iceland

Between Tradition and Liquid Modernity

Summary

The author of the book analyses popular topics and narrative strategies in Icelandic films. The research covers local versions of black comedies, road movies and crime stories as well as different figures connected with the motif of struggle between tradition and modernity.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- About the author

- About the book

- Citability of the eBook

- Contents

- Preface: A Cinematic Terra Incognita?

- Introduction: The Imaginary Island: From a Literary Myth to On-screen Stereotype

- Constructing a Myth

- (Re)constructions of the National Liberation Myth

- Cinematic Reinterpretations of Myths and Stereotypes: From the Cinema of Heritage to the Postmodern Irony

- Iceland as the Other (and Unknowable)

- Part One: Reconfiguring Utopias: Nation Building and Cinema

- 1 Nature, Countryside and the City: The Ideologies of Nation Building

- Introduction

- Country and the City in the Works of the Pioneers of Icelandic Cinema

- Country and the City in Selected Films of Friðrik Þór Friðriksson

- Conclusions: On the Crossroads of the Liquid Modernity

- 2 In the Land of the Great Narrations: Chronotopias, Uchronias and Nostalgic Past

- Introduction

- Nostalgic Returns to the Past

- In the Kingdom of Distance and Irony

- Elves and Globalization

- Conclusions

- 3 Tradition, History and Liquid Modernity in Icelandic Musical Documentaries

- Introduction

- Rock in Reykjavík: Rebellion Against the Tradition and Narcotic Taste of Cultural Colonization

- Screaming Masterpiece: “Selling Out the Tradition and History”

- Heima: Community, Nation and Homeland as the Elements of the “Everyday Patriotism”

- Backyard: Beyond Nation and Nature

- Conclusions

- Part Two: Figures of Tradition, Crisis and Change

- 4 Of Fishermen and Their Ships: Marine Motifs, Cruel Nature and Zeitgeist

- Introduction

- The Spirit of the Sea and the Wind of Change in the Documentary Cinema

- The Cinema of Seafaring and the Allegories of Crisis

- Conclusions

- 5 Restless Daughters of Freyja: Female Soul of Icelandic Cinema

- Introduction

- Historical Background: Female Characters in Nationalistic Narratives

- Cinematic Female Protagonists as Victims of Violence

- Vamps, Warriors and New Models of Independent Women

- Conclusions

- 6 The Curious Case of Anti-Vikings

- Introduction: Generation X and the Crisis of Manhood

- One Flew Over the Puffin’s Nest: Friðrik Þór Friðriksson’s Angels of the Universe

- The Plastic Sorrows of the Icelandic Peter Pan: Baltasar Kormákur’s 101 Reykjavík

- The Last Skáld? Marteinn Thorsson’s Rokland

- The Tragic Fall of Icelandic puer aeternus: XL by Marteinn Thorsson

- Conclusions

- Part Three: Reimaging Utopia: Genres and Transnational Dreams

- 7 Icelandic Crime Stories

- Introduction

- Literary Roots

- First Steps into the Cinematic Genre: Reynir Oddsson’s Morðsaga

- Flirting with Neonoir

- Reinterpretations of the Gangster and Police Movie

- Conclusions

- 8 At the Edge of World: Black Comedies and the Allegories of Crisis and Isolation

- Introduction

- Between Utopia and Dystopia – (Re)constructions of the Concept of Insular Life

- Allegories of Social and Economic Crisis

- Conclusions

- 9 Cinematic Journeys Around Iceland

- Introduction

- The First Journey: The Island of Heterotopias and Pagan Beliefs

- The Second Journey: The Island of Stereotypes and Conventions

- The Third Journey: Bitter Flavor of Tourist Utopia

- The Fourth Journey: Pop-cultural Anti-utopia and Entrance into the Void

- The Last Journey: Escapes from Utopia

- Conclusions

- Appendix: Tradition and Liquid Modernity in Documentary Cinema

- Introduction

- Part 1. Reinterpretation of the Elements of National Discourse

- Part 2. How to Survive After the Crisis?

- Conclusions

- Afterword: Notes After the Year 2016

- List of Figures

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Bibliography of the Previously Published Parts of the Book

- Index

Preface: A Cinematic Terra Incognita?

Most people associate Iceland with a popular tourist destination – full of unusual attractions, such as glaciers, geysers and crippling air traffic volcanoes. Many others may think of Vikings, sagas and financial crisis of the year 2008. Flying to Reykjavík for my first scholarship in September 2010, I was aware that this northern land also gave the world some great writers, gifted musicians and not necessarily widely recognized cinema. This last field of culture is supposed to be the new subject of my academic interests that finally transformed into six years of researching project.

At the beginning of my work, I had known only a few films – mostly those of Friðrik Þór Friðriksson and recognizable in Europe movies of Baltasar Kormákur. Gradually, during my scholarships at the University of Iceland (Háskóli Íslands) and in the course of my queries, both in the National Film Archive of Iceland and the Icelandic Film Centre, I discovered more and more data on the unknown authors and themes.

At the very first glance, the Icelandic cinema may seem to a foreign viewer as the one obsessively repeating the same themes and topics which, by the way, are not always easy to comprehend without the proper historical and culture background. Closer encounters with the most interesting films from this Nordic island, however, compensate the aforementioned difficulties, giving the opportunities to observe the birth and development of small (but brave) energetic and ambitious cinema. Such an experience also allows to analyze the problems related to the system of film production in the country populated by mere 330,000 inhabitants and indicates the challenges of introducing local culture abroad.

For all these reasons, I decided to discuss in this monograph over 100 films that are, predominatingly, created in Iceland by Icelanders during the years 1906–2016. They are casted with local actors who speak in their native language. These criteria may seem too radical in times of international co-productions, European movie grants and globalization, but the complexity of cinematic production, promotion and distribution system in the homeland of Björk explains such limitations. In a sense, these restrictions also reflect some Icelandic legislations brought to life in Reykjavík in 1978 within the creation of The National Film Archive of Iceland and the Icelandic Film Fund.

Taking into consideration all these elements, at the beginning of my cinematic researches I analyze some ideological contents of the different narrations ←9 | 10→referring to the idea of supporting the utopian and romantic view on Iceland. In this part of the book, I introduce some inspiring academic terms, such (among others) as John Urry’s tourist gaze, Michel Foucault’s heterotopia, Kristen Hastrup’s uchronia and Jean Baudrillard’s simulacrum, that will be used in next chapters. Also the key figures of Icelandic national identity are described here, altogether with the theories of imaginary communities and invented nationalism. Finally, the reader will find some references to the humanistic geography (and such concepts as Les Lieux de Mémoire and Les Lieux d’imagination).

The first chapter of the book includes the films with nostalgic indications of the past and movies presenting antinomies of life in the rural and urban areas. These themes are often linked in Icelandic cinema from 1980s with the motif of symbolic struggle between the new and old, the youth and senility or the local and foreign, and used to strengthen the national identity. Chapter 2 analyzes the cinematic images that refer to the local sagas and legends with the heterotopian or uchronian perspective. In the third chapter, once again I write about the films related to the popular motif of the generations’ conflict, connected with the powers of nature and the opposing forces of tradition and modernity. This time, however, my researches are concentrated on the popular genre of musical documents.

Next three chapters from the second part of the book provide the interpretations of some characters selected from the pantheon of the Icelandic collective imagination. Their constructions indicate significant social changes and contain allusions to the figure of the Other. First, I research the figures of fishermen. They were eradicated from the symbolic imaginarium of the Icelandic nation by the Danish colonial politics but have returned in 20th- and 21st-century local cinema in various contexts. The next two parts of the book focus on the movies about strong, independent woman and the immature male characters (that I called the anti-Vikings). Both cases are interpreted as meditations on so-called postmodern condition, which includes different forms of social, individual and cultural crises.

The sections from the third part of the book focus on the ironic or dystopic look at the utopian idea of North and Icelandic national identity. Different attempts to deconstruct some popular motifs from previous chapters, such as the conflict of generations, the fear of foreign cultural influences and the feeling of geographical and mental isolation, are analyzed here, based on the genres of black comedy, road movies and crime cinema. In the plots of these films, I try to track strategies that reimage tourist simulacra of Iceland into the ironic figures and allegories, once again, indicating some different types of crises.

←10 | 11→The context of postmodern changes is also discussed in the selected studies on the Icelandic documentaries which are placed in the appendix of this monograph. These non-fictional films often refer to the problems and themes that were described on the basis of the feature movies in the previous parts of the book.

Finally, the book ends with an afterword, presenting a panorama of Icelandic movies that were produced after the year 2016, when my official researches from the grants finished. It is an attempt to sum up the evolution of the Icelandic cinema and indication of its transnational successes, achieved in the second decade of the 21st century.

In all chapters I am also interested in different reinterpretations of the clichés connected with the stereotypical images of Iceland and its inhabitants, constructed by the local and foreign narrations. Such strategies often include some intertextual games with the viewers, attempting Icelandic directors use the transnational branding of the local contents.

Last but not least, I hope that the reading of this book will outline the vision of the unknown film realm, which, thanks to the sincere commitment and hard work of many people, became a dynamically spreading image, eclectically weaving together selected myths, stereotypes and modern means of expression.

The Imaginary Island: From a Literary Myth to On-screen Stereotype

Constructing a Myth

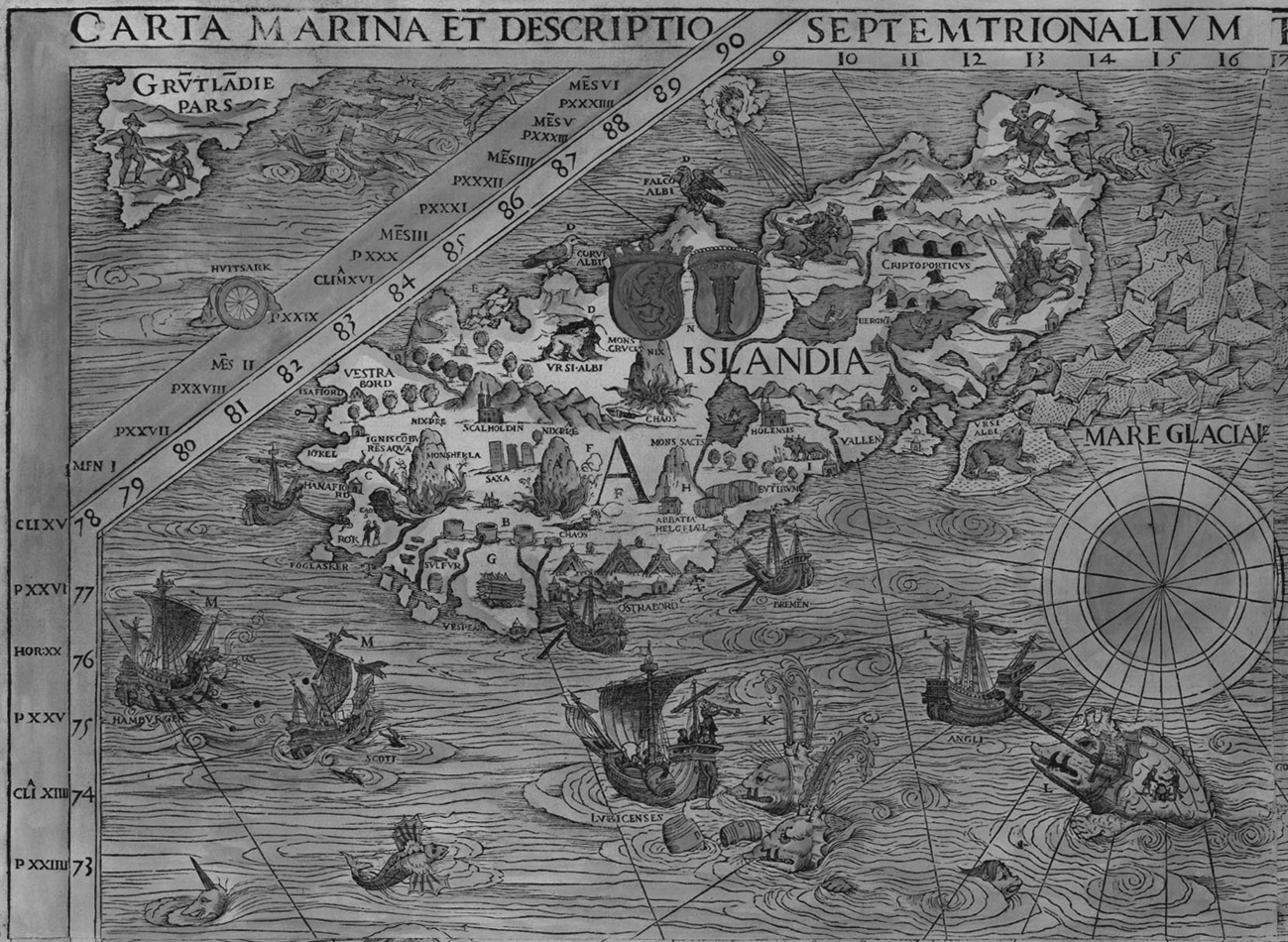

The protagonists of Julius Verne’s A Journey to the Centre of the Earth, a novel written in 1864 and inspired by Icelandic sagas, decide to sail to the far North to reach one of the craters under the Snæfellsjökull glacier to get from there to the center of our planet. Obviously, the dreams of traveling to the 19th-century Verne’s fictional “land of fire and ice” are rooted in much earlier times. They were spun by the first sailors who set off from Europe to explore the unknown. The ancient marine wanderers initially identified a lone island at the end of the ocean with the farthest land – mythical Ultima Thule. As Pierre Lévêque fairly points out, the ancient history is

“a period when brave pioneers explored new ocean trails. Euthymenes and Pytheas arrived at The Pillars of Heracles. The first one crossed the western coast of Africa, most likely reaching Senegal. The other one sailed north, visited the British Islands (named that way for the first time), Scandinavia and the foggy island of Thule (Iceland), only to come back to Marseilles, where he wrote diaries that raised general disbelief”.1

In his description of the fantastic lands, Umberto Eco invokes not only this boundary imagination but also creates the first maps of imaginary space, which include, for instance, the volcanoes and fantastic creatures guarding them.2 According to Eco,

“the myth of Thule merged in time with the one about Hyperboreans. The ancients perceived Hyperboreans (those who live farther than Boreas – the personification of the ←13 | 14→northern wind) as people occupying the areas located far away from Greece. This perfect land was ceaselessly lit by the sunshine for six months a year. Hecataeus of Miletus (6th–5th centuries BC) placed Hyperboreans even farther north, between the ocean (which surrounded all of the known lands) and Riphean Mountains (a legendary mountain chain of uncertain location, sometimes placed far North, and sometimes nearby the Danube Delta)”.3

The descriptions of such mythical island combine ambiguous narrative strategies – marked by journey reports and phantasmal imagination. Words of disbelief can be found in the comments included in Polybius’ The Histories.4 This work included the descriptions of the heroic journeys of Pytheas, who presumably reached not only the British Islands, but also the gates of far North. Researchers of imagology and humanistic geography5 emphasize that the unrealistic status of the farthest land merged over the centuries with marine reports from Norway (or, more generally, today’s Nordic areas), areas often compared to the Fortunate Isles.

In his work Southern Perspectives on the North, Peter Stadius differentiates four phases of development of perception of the northern region of Atlantic. The first one, already mentioned, is Greek antique,6 which recalls the Hyperborean phantasm. In the times of the Roman Empire, the pejorative perception of the North as a savage and wild land is enhanced further. Stadius quotes texts like Germania by Tacitus, in which – in his opinion – the first literary comparisons of the Northern people’s (in this case Germanic tribes) barbaric alterity and civilized South culture, perceived then as the center of the world, has been drawn. Genesis of those negative perceptions is related to the reinterpretation of theory of elements developed by Aristotle, in which the northern area has been identified with water, moist and phlegm. And that, according to Stadius, caused the “cold” perception of its inhabitants.7 He also remarks that the negative descriptions of ←14 | 15→those territories and barbaric behavior of its inhabitants (all communities whose territories and models of behavior did not fit in the boundaries of the Empire) were confronted in that time with earlier, hyperborean narrations, as those present in the texts of Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus.8

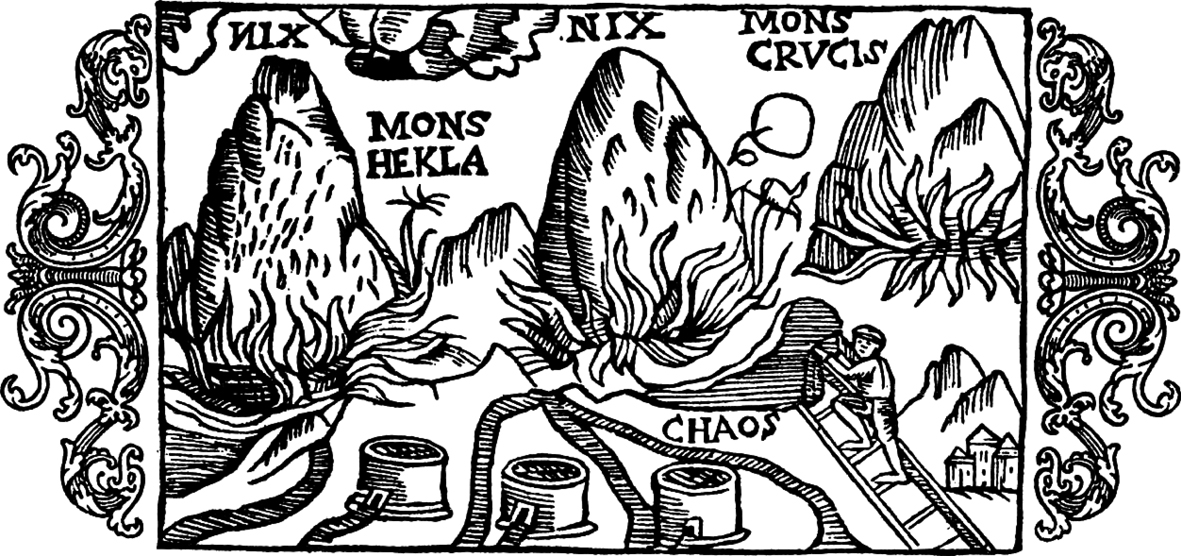

Medieval reports of Celtic sailors and Irish monks re-established the utopian perception of Iceland.9 In his The Idea of North, Peter Davidson proves that “the fire of Icelandic volcanoes strengthened its reputation as a place of miracles. Medieval cosmography known as The Carte of the Warld describes Iceland as a place of strange, marvellous things (mony ferlyis), where boiling water can burn rocks and iron (scaldand watter that birnis baith stanis and Irne)”.10

←15 | 16→The mythology of fantastic descriptions of the island will be also supported by associating its status with Scandinavia. Stadius proves that another important phase of change in the perception of this area is related to the internal attempts made to reactivate the myth of Hyperboreans in Renaissance. In 1555 in Rome, a Swedish Roman Catholic priest Olaus Magnus published a description of a Northern people called Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus. A year before, in the same city, a posthumous work of his brother Johannes was published, Historia de omnibus Gothorum Sueonumque regibus. Both texts were popularized in Sweden in the 16th and 17th century. Their authors try to place the islands of happiness in the territory of Northern Atlantic, and these attempts connote with the idea of Scandinavia as the “mother of nations”. The strategies based on putting Northern rulers into the mythical and historical order of old Europe can also be found. Those measures had, obviously, an ideological character, as they were related to the reformation. And because of that, they inspired other philosophers in various ways. One that deserves to be mentioned here is Professor Olaus Rudbeck (known as Olof Rudbeck Senior), who lived in Uppsala more than a hundred years later. In his Atland eller Manheim (1679–1702, Latin: Atlantica), he celebrates the extraordinary status of the Northern territories, which had been marginalized on the maps of Europe.11 Rudbeck’s activities have clearly an ideological character, as they are related to the 17th-century war between Protestant Sweden and Catholic Spain. That is why the references to Gothic legacy can be found in them (as well as in an earlier work of Johannes Magnus).12 The Goths have been drawn by the author of Atlantica from Getica (6th century), written most likely by a Roman chronicler Jordanes.13 Magnus’s descriptions of the North were seen as an ideological response to the Spaniards’ vision of the South as the cradle of the European culture. The search for Gothic roots of the Northern people will reappear in the Scandinavian history in the 19th and 20th centuries.

But let us get back to the evolution of the perception of Iceland. Because of its atypical geological structure, this land did not always have its utopian character. Peter Davidson provides some 16th- and 17th-century descriptions of the island that present it not only as a land of miracles14 but also as a volcanic landscape, which resembles a place of suffering for the sinners. Such a dystopian ←16 | 17→perspective can be found in the reports of the aforementioned Bishop Olaus Magnuson, who informs the readers of one of his texts that “it is believed to be a place where impure souls find punishment or atonement. Souls, drowned spirits or those who died violently, have been surely seen there, taking care of their human business”.15 Similar antinomies in the depiction of the North and Iceland itself can be found in European literature written throughout the following centuries. Kristinn Schram, who took part in a research project Iceland and Images of the North,16 correctly points out that

“in many cases it is very difficult to differentiate the perception of Iceland from more general descriptions of the North. For the North concept is full of extremes and ambiguity. […] From dystopian visions of barbarity to enlightened utopia – pendulum [of perception] sways from civilized to wild”.17

It is natural then that even in the works created in Iceland many years later, the contrast between a “hellish character” and a utopian landscape of solitary land, located at the end of the world, is still much alive.

←17 | 18→In the 18th and 19th centuries, the phantasmal status of the island got even stronger. Ideas of romantic journeys pushed more idealistic daredevils to seek unknown exaltation in the distant Northern lands. Even though the expedition to circumpolar territories did not match the concept of a Grand Tour,18 there have been some travelers who set out into these areas. They were mostly inspired by the idea of discovering the roots of European culture in, once again alive, Germanic mythology and aforementioned Gothic fiction.19 To this day, the observations made by those travelers remain a suggestive example of difficulties related to the lack of suitable means of expression that could be used to describe the dissimilarity of the landscape and Otherness of its inhabitants. The authors of 18th- and 19th-century journals describing travels to the North20 often use the expressions typical for Orient travels, whose specifications and ideological implications are studied in the classic work of Edward W. Said.21 This narrative strategy is well illustrated in the texts of wanderers culturally related to Poland. One of them, Edmund Chojecki, in 1856 described Iceland with the following words:

“Summits covered by everlasting snow, extinct volcanoes, breathing craters covered by lava glaze and basalt columns spread on the ground – real Babylonian temple, overthrown by a prophet in fury”.22

←18 | 19→It is worth mentioning that such exalted descriptions of Icelandic Otherness were a result of licentia poetica, as – according to Karen Oslund – most of the travelers coming up to the island in the 18th and 19th centuries were well aware of the existence of glaciers and volcanoes. Glaciers could be observed, for instance, in Switzerland, a very fashionable travel destination at that time, while volcanoes, on the other hand, could be admired in Italy.23

Most likely that is the reason why these reports from Iceland, apart from oriental imagery, contain rhetorical figures popular at the time and compare its inhabitants to the figures from ancient Greece or to the societies of Oceania, untainted by civilization. That is the effect of both internal and external reactions to the strategy of presenting Icelanders as poor peasants and fishermen, which are also present in numerous descriptions of the journeys to the island.24 John R. Gillis, who lived in Iceland for some time, dedicates one of the chapters in his book Islands of the Mind to this antinomy in the perception of Iceland. He proves that

“the insular character of Icelandic identity was actually born on the continent. The feeling of uniqueness of its inhabitants was shaped to a large extent by the travelers who visited Iceland in the 18th and 19th century, who romanticized Icelanders in the same way they did in the case of the nations of Oceania, claimed to be especially virtuous and unspoiled by the civilization”.25

However, contrary to Gillis’ conceptions, the examples of internal idealization of the “homeland of the sagas” can be found in the reckoning of indigenous islanders, who were recovering their national pride in the 19th century and became more and more courageous about the thought of independence.

Details

- Pages

- 330

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631778647

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631779156

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631779163

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631779170

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15131

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (June)

- Keywords

- Nordic cinema film narration film genres national cinema transnational cinema postmodernity

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2019. 330 pp., 70 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG