The Aesthetic Revolution in Germany

1750–1950 – From Winckelmann to Nietzsche – from Nietzsche to Beckmann

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. The birth of the aesthetic man in Germany

- 1.1. The birth of the aesthetic man. Johann Joachim Winckelmann

- 1.1.1. The romantic rebellion

- 1.1.2. Critical voices: from Heinrich Heine to Georg Lukács

- 1.1.3. In defence of the romantic rebellion

- 1.1.4. The aesthetic revolution as an alternative to the mechanistic world view.

- Descartes (1596–1650)

- Francis Bacon (1561–1626)

- Isaac Newton (1642–1727)

- 1.1.5. The historical sense

- Giambattista Vico (1668–1744)

- Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716)

- Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)

- Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) and Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835)

- 1.2. Friedrich Schiller: Beauty and Freedom

- 1.3. Friedrich Hölderlin: Beauty and Revolution

- 1.4. Heinrich von Kleist: Radical Beauty

- 1.5. Richard Wagner: Regeneration of the culture

- 2. Nietzsche as culmination point of the aesthetic perspective

- 2.1. On Nietzsche’s life

- 2.2. Nietzsche’s criticism of historism

- 2.3. Nietzsche’s gospel of art.

- 2.3.1. Dionysus against Christ

- 3. The ambiguity of the aesthetic revolution

- 3.1. The Fin de siècle: End or turning point? Between decadence and awakening

- 3.1.1. The Fin de siècle as a turning point

- 3.2. The conservative Revolution. A discourse

- 3.3. Stefan George: Art and ‘Reich’

- 3.4. Oswald Spengler: retrograde prophet?

- 3.5. Thomas Mann: Aesthete nolens volens

- 3.6. Gottfried Benn: architect of nihilism

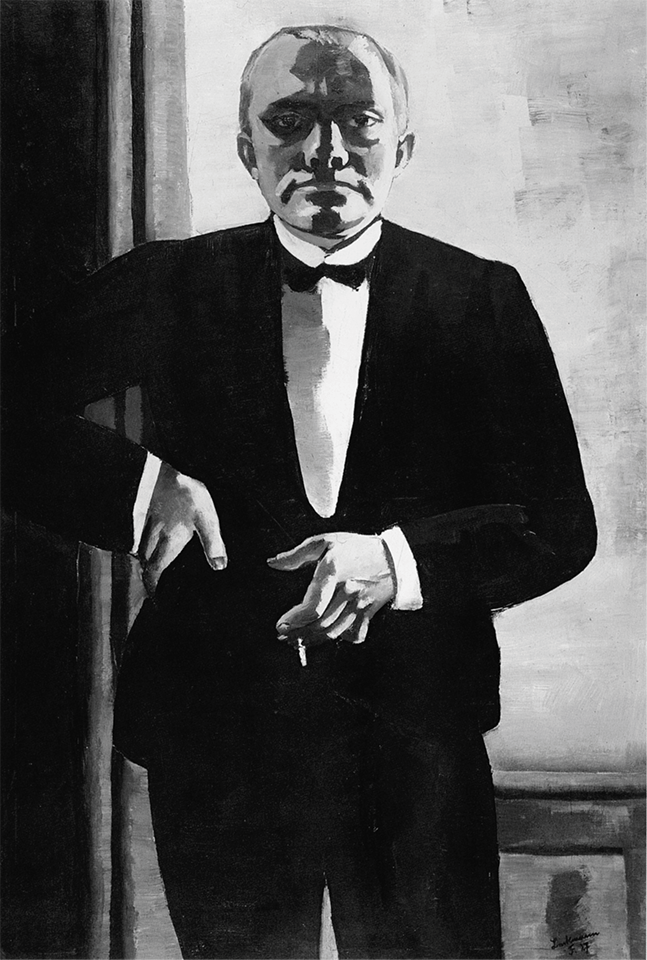

- 3.7. Max Beckmann: the artist as the new god

- 3.7.1 Beckmann’s Work

- 4. Epilogue

- 4.1. Martin Walser’s novel A Gushing Fountain

- 4.2. The necessity of an aesthetic perspective for the modern era

- Illustrations

- References

- Chapter I

- Johann Joachim Winckelmann

- Romantic Rebellion and mechanistic world view

- Historical Sense

- Friedrich Schiller

- Friedrich Hölderlin

- Heinrich von Kleist

- Richard Wagner

- Chapter II

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Chapter III

- Fin de siècle

- Conservative Revolution

- Stefan George

- Thomas Mann

- Oswald Spengler

- Gottfried Benn

- Max Beckmann

- Epilogue

- Index of Names

Meindert Evers

The Aesthetic Revolution

in Germany

1750-1950

From Winckelmann to Nietzsche – from Nietzsche to Beckmann

![]()

Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

ISBN 978-3-631-71668-7 (Print)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-71976-3 (E-PDF)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-71977-0 (EPUB)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-71978-7 (MOBI)

DOI 10.3726/b10944

© Peter Lang GmbH

Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften

Frankfurt am Main 2017

All rights reserved.

PL Academic Research is an Imprint of Peter Lang GmbH.

Peter Lang – Frankfurt am Main · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright. Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution. This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

About the author

Meindert Evers was assistant professor at the University of Nijmegen, NL. He has published numerous articles and books (e.g. on Proust) in his specialist area of European culture and intellectual history. He lectures on topics of European cultural history at the Zentrum Seniorenstudium of the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich.

About the book

The Aesthetic Revolution in Germany refutes the stereotypical image of Germany as the country of romantic but unworldly poets and thinkers. In 1750, an aesthetic revolution takes place in Germany, at the beginning of which stands J.J. Winckelmann. The romantic movement (Schiller, Hölderlin, Kleist) paves the way for this aesthetic revolution, which Heine is one of the first to criticise. Since then, criticism has never fallen silent. Opposing the rationalisation of the world (Wagner), the aesthetic revolution climaxes in the philosophy of Nietzsche. During the 1920s and 30s, it becomes a conservative revolution (George, Spengler, Th. Mann, Benn) and fails inevitably. Beckmann and M. Walser show that particularly after 1945 the aesthetic perspective is still necessary.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

1. The birth of the aesthetic man in Germany

1.1. The birth of the aesthetic man. Johann Joachim Winckelmann

1.1.2. Critical voices: from Heinrich Heine to Georg Lukács

1.1.3. In defence of the romantic rebellion

1.1.4. The aesthetic revolution as an alternative to the mechanistic world view

1.2. Friedrich Schiller: Beauty and Freedom

1.3. Friedrich Hölderlin: Beauty and Revolution

1.4. Heinrich von Kleist: Radical Beauty

1.5. Richard Wagner: Regeneration of the culture

2. Nietzsche as culmination point of the

aesthetic perspective

2.2. Nietzsche’s criticism of historism

2.3. Nietzsche’s gospel of art

2.3.1. Dionysus against Christ

3. The ambiguity of the aesthetic revolution

3.1. The Fin de siècle: End or turning point? Between decadence and awakening

3.1.1. The Fin de siècle as a turning point

3.2. The conservative Revolution. A discourse

3.3. Stefan George: Art and ‘Reich’

3.4. Oswald Spengler: retrograde prophet?

3.5. Thomas Mann: Aesthete nolens volens←7 | 8→

3.6. Gottfried Benn: architect of nihilism

3.7. Max Beckmann: the artist as the new god

4.1. Martin Walser’s novel A Gushing Fountain

4.2. The necessity of an aesthetic perspective for the modern era

Since the second half of the 18th century, a revolution has been taking place in Germany, an aesthetic revolution. At the start of this upheaval stands the figure of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the first ‘apostle of beauty’. This revolution strikes at the time of Sturm und Drang and romanticism. Poets like Schiller and Hölderlin proclaim the aesthetic individual. Until 1848, this revolutionary movement expresses itself mainly theoretically and in literary and musical forms. However, after 1848 other voices become loud. They insist on an implementation of the ideal. One of these voices is Wagner. But more urgent and more dangerous is the wake-up call from Friedrich Nietzsche. In his thinking, the longing for a change reaches a climax.

The aesthetic revolution turns into a German revolution. The latter may have failed pitifully, but that does not reduce the necessity for an aesthetic revolution in the least. The art of Gottfried Benn and Max Beckmann aims to show that modern reality can only be justified by aesthetic means.

Why an aesthetic revolution arose in Germany in particular, why this aesthetic revolution in the Fin de siècle became a conservative, a German revolution and finally discredited itself by becoming political, is the topic of this book. Still, the correctness of this revolution of beauty is not denied.

I am aware that particular parts of this book could be interpreted as polemical and provocative. It will become clear that I am resisting a negative and materialistic interpretation of romanticism. It may be provocative that I uphold the primacy of art – as opposed to the primacy of (radical) politics.

The French political revolution was, contrary to conventional opinion, the first totalitarian attempt to de-individualise people, to turn them into robots. It strove to put into practice a purely mechanical idea of life. Thanks to the intervention of the allies, the radical demands of the French Revolution could not be pushed through. What are known as human rights are actually the fruits of the American Revolution. This Christian enlightened revolution is the only alternative to the German aesthetic or the French political revolution. For an understanding of the French Revolution, the diagnosis and analysis of the German philosopher Hegel is still of significance; the glorification of the events of 1789 is a French Republican fabrication of the late 19th century.

The German aesthetic revolution was the heroic, and in a particular period, tragic attempt to give the absolute a bodily form on earth. The beautiful is not to be realized on this earth; however, this study still seeks to awaken an understanding←9 | 10→ of this impossible longing. The artistic, the aesthetic perspective on reality is the highest possible and also the only one which, according to Nietzsche, remains for the modern godforsaken individual.

The main character in this book is Friedrich Nietzsche. He entered my life early. I was in secondary school when I read Zarathustra for the first time. From the first moment, his thinking enchanted me through his language – and the fascination remained. What fascinated me? His diagnosis of the age and his belief in art. Nietzsche is the aesthetic individual par excellence. His credo runs: only art reconciles us with reality. He is not uncontroversial. Not a few have made him responsible for the German catastrophe between 1933 and 1945. He is a dangerous philosopher. One should know how much Nietzsche one can bear: too high a dose can be fatal.

My book has three chapters. The first chapter reports on the aesthetic revolution which took place in the second half of the 18th century. Johann Joachim Winckelmann is its herald. In the period from 1760 to 1848, the aesthetic perspective becomes dominant; Schiller, Kleist, Hölderlin and Wagner propagate an aesthetic revolution as the answer to the radical politicisation and rationalisation of the world. This great spiritual revolution, which also shows itself in a new perspective on history, is defended in this book against those who see in it only the price of political backwardness.

In the second chapter, Nietzsche is discussed. In him, the aesthetic revolution reaches a climax. He radicalises the ideas of Schiller, Hölderlin and Wagner. The only means remaining for modern people to justify their existence is art. Neither science nor faith, which itself has also been made scientific, is in a position to do so. Nietzsche’s dream of a new human being will occupy the following generations.

The ideal wants to take shape: the topic of the third chapter is the ambivalent character of the aesthetic revolution. This is illustrated with a movement like Art Nouveau which is the attempt to place life under the primacy of beauty. How the aesthetic revolution in the 20s and 30s develops into a conservative German revolution is represented by poets and cultural philosophers like Stefan George, Oswald Spengler and Gottfried Benn. The latter briefly placed his hopes on the year 1933.

Is, as Thomas Mann thought, the aesthetic perspective discredited by the events of the 30s and 40s? The painter Max Beckmann and the poet Gottfried Benn remain convinced, even after 1945, that the modern age can only be justified by an aesthetic view. Are they right?←10 | 11→

In the epilogue, the question is addressed whether the aesthetic perspective can continue to exist in the shadow of Auschwitz. How current this question is, is shown by the discussion about Martin Walser’s novel A Gushing Fountain. Is God dead, or is only the German God dead? If Nietzsche’s diagnosis is still valid, the world today is in great danger. Then the aesthetic perspective is more necessary than ever.

The original Dutch edition appeared in 2004 from the Damon publishing house in Holland under the title: De aesthetische revolutie in Duitsland 1750–1950. Revolutionaire schoonheid voor en na Nietzsche. I have thoroughly revised and enlarged the text for the German edition, which appears simultaneously with the present English edition, but without any dilution of thesis presented. Chris Costello, who already translated my Proust book in 2013, also translated this book from the German. I am very grateful to him. I have not overloaded my work with notes, but sources are given for all quotations. Where no translation was available – far from all of the essays and speeches by Gottfried Benn or the letters of Max Beckmann have been translated – Chris Costello also took on this task. The literature index at the end of the book lists the literature used per chapter and also includes recommendations for further reading.←11 | 12→

No. 1 Self-Portrait in Tuxedo, 1927. Cambridge/Massachusetts, Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University, Museum Purchase. Source: Carla Schulz-Hoffmann, Max Beckmann. ‘Der Maler’, München 1991.

1. The birth of the aesthetic man in Germany

1.1. The birth of the aesthetic man. Johann Joachim Winckelmann

The aesthetic revolution in Germany begins with Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768). With Winckelmann, this revolution articulates itself as a protest against affectations and mannerisms, against the academic and the conventional, against the French classicistic model, against a bloodless, decorative classicism which has been robbed of its original vitality. Winckelmann’s protest against French classicism was basically a protest against the mechanical and materialistic view of the world which characterised the French Enlightenment of the 18th century as a result of Cartesianism.

In the France of Descartes, the esprit géométrique is most deeply anchored, most radically practised. And since Louis XIV, the specifically French culture spreads across all countries and continents – including the German states. Frederick the Great, a contemporary of Winckelmann and his sovereign, spoke and wrote French; his taste – as shown in the Sanssouci palace, built in the Rococo style – was completely derived from France. When Shakespeare was performed during his time, the Prussian king could only see in it a modern lack of taste. The courts of the German aristocrats are especially influenced by the French example, to the displeasure of many young intellectuals. Their vision is of a new, national culture which should be founded on authenticity, naturalness and simplicity.

From the second half of the 18th century onwards, the Greeks replace the Romans as the ideal. With his History of Ancient Art (Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums) (1764), Winckelmann decisively shaped this revaluation. He, the son of a cobbler in Stendal, started an aesthetic revolution in Germany.

Winckelmann held that the culture of his age, which he described as artificial and conventional, could only be reformed if the Greeks, if Greek culture was taken as the model. He connected with it a (new) style ideal.

His name is wrongly associated with neoclassicism. His religion of beauty can better be seen as ‘romantic’. He loved Greek art with an almost erotic passion. In his main work History of Ancient Art, his descriptions of Greek sculptures like the Torso of Hercules and the Apollo of Belvedere are literary highlights. The passion with which he views the classical works finds its expression in precise and still poetic descriptions. It makes his History of Ancient Art the opposite of a←13 | 14→ classicistic work, although his definition of classical beauty had given rise to it. It is not Winckelmann from whom Nietzsche later distinguishes himself, but from his caricature.

With respect to Greek art, Winckelmann heralds a new beauty. To describe this beauty he uses words like “serene”, “mild” and “harmonious”. He distinguishes his ideal of beauty from that of the Baroque, which he saw as extreme and unnatural. He distinguishes it from the geometrical conceptions which dominated in French academicism and classicism. Beauty, according to Winckelmann, cannot be measured or calculated. There is no fixed yardstick for art to conform to. Not the intellect, but only “good taste” – here he means the aesthetic sense – is capable of experiencing beauty. Beauty cannot be grasped by the intellect. It can only be felt.

Beauty, Winckelmann writes in Remarks on the History of Ancient Art (Anmerkungen über die Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums) (1767), is mainly expressed by the body of a young human. Because the young body only knows gentle, flowing transitions without hard edges. Many times Winckelmann defines beauty as a manifold unity – a very Leibnizian idea. He compares it with the sea which appears flat in the distance, but the surface of which, seen close up, is set in continuous movements by little waves.1

With this idea, Winckelmann distinguishes himself from an art which is only heroic, like so much French or Italian art of the late Renaissance and the Baroque. This evil starts with the art of a Michelangelo and continues in the art of a Bernini. Winckelmann accuses the latter of brutality and unnaturalness. Winckelmann’s concept of art is also distinct from the naturalistic art of the Dutch. The artists of Dutch realism only have an eye for detail. The defect of this art is that they do not reduce the disharmonious – particular ugly elements in the face, such as a nose that is too sharp, a wart, a deep skin fold. According to Winckelmann, an artist who chooses the Dutch path can never attain true beauty. This can only happen on the Greek path. However, this also involves the danger that the unity, the formal is overemphasized. Winckelmann’s ideal figure is therefore not the line or the circle, but the ellipse. It best symbolises unity of diversity and simplicity. But Greek art did not achieve this harmony immediately. Winckelmann found ancient Greek art still too hieratic.

That Winckelmann is unjust to Dutch painting and forgets that the realism of the Dutch school is magical realism, in many cases, which will not be pursued here.←14 | 15→

Winckelmann’s ideal of beauty is embodied in the Greek art of the Pericles era, a period of around fifty years from the Battle of Salamis (480) to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (431). In an era when tragedians like Aeschylus and Sophocles staged their dramas, in which Plato taught and in which Polyclitus and Phidias are active. In fact, his greatest admiration does not apply to the classical, but the late classical and early Hellenistic sculpture of Praxiteles and Lysippus. What is special about Winckelmann is that he discovers his new, wild Greeks not in the archaic art, which he cannot yet appreciate, but in the works of late classical artists which appear to us who were born later as too smooth, too polished, in fact too classicistic. Both the so-called Torso of Hercules as well as the Apollo of Belvedere, both of which leave an indelible impression on Winckelmann and which represent icons of great Greek art for him, are Hellenistic works or Roman copies.

Winckelmann’s favourite idea of Greece is that of a ‘Gymnasion’ in which naked youths test their strength on one another in the arena. The youth, which means not-yet, the both-one-thing-and-the-other, the indefinite, where it is unclear in a particular perspective whether they are a boy or a girl. For Winckelmann, the youth is an almost androgynous figure, which is expressed most beautifully, most completely in the Apollo of Belvedere.

According to Winckelmann, contemporary culture can only be restored if it takes this great Greek culture as a model. In his Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst) (1755) he already raises Greek art to the sole standard for every later art: “There is but one way for the moderns to become great, and perhaps unequalled; I mean, by imitating the ancients.”2 In the History of Ancient Art, the greatest works of the normative Greek art are described and interpreted. It is interesting that he may describe Greek sculpture in the context of Mediterranean cultures, but accords Greek art the absolute priority therein.

He regards the essence of Greek art as consisting of harmony: visual art must be restrained in its expression. If it is too passionate, the harmony which the art should awaken in the beholder is distorted. Art should be characterised by “noble simplicity and sedate grandeur”.3 Even in the dramatic Laocoön group, excavated in 15064, these attributes can be found. The desperation and the suffering of the←15 | 16→ father, who was punished by the gods for warning the Trojans about the wooden horse and strangled by sea snakes together with his sons, is expressed by the attitude and position of the bodies, without their facial features being distorted: “Laocoön suffers, but suffers like the Philoctetes of Sophocles: we weeping feel his pains, but wish for the hero’s strength to support his misery.”5

Winckelmann sees the development of art as an organic whole with its blossoming and its decay. His History of Ancient Art is not satisfied with describing art on the basis of the biographies of artists as Vasari did in his time. Art is observed in its historical context. The second part of his History of Ancient Art investigates the conditions in which Greek art was able to arise.

Winckelmann’s starting point is always the work of art itself which he regards with a love, with a passion, and which he describes with such precision that the reader receives an irresistible impression of the beauty which Winckelmann felt when he looked at it. In Winckelmann one finds a unique combination of sensual observation and normative thinking. His rather distant language seems to be inflamed under the impression of the work of art. His famous descriptions of the Torso of Hercules and the Apollo of Belvedere form the oldest core of his main work.

Details

- Pages

- 362

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631716687

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631719763

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631719770

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631719787

- DOI

- 10.3726/b10944

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (April)

- Keywords

- Conservative revolt Christian enlightenment Romantic movement Modernity

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2017. 362 pp., 5 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG