A Splendid Adventure

Australian Suffrage Theatre on the World Stage

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

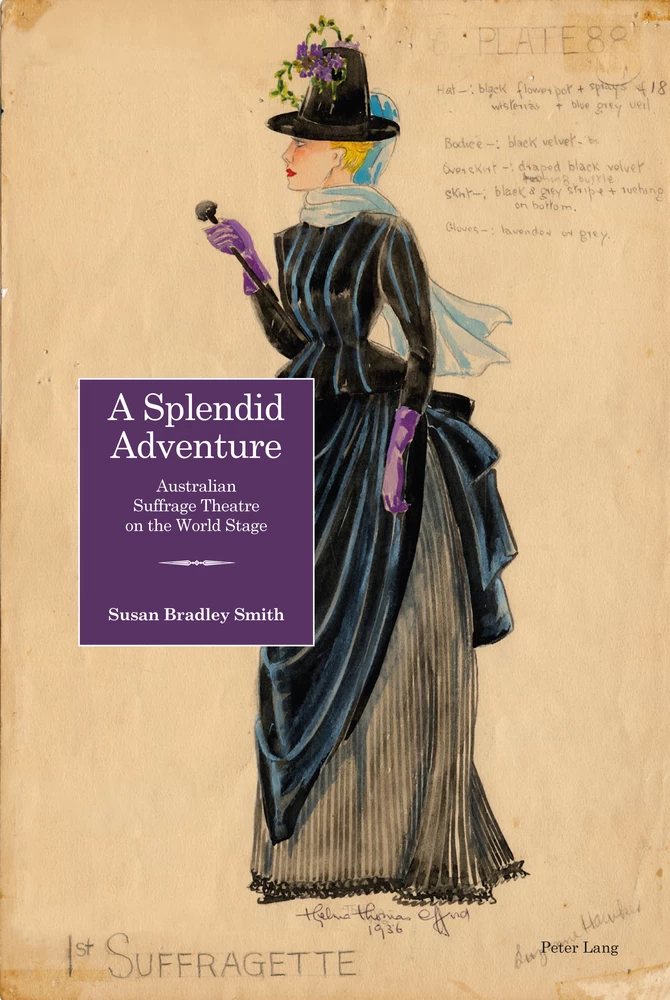

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Suffrage Theatre and the Women’s Movement: A Short History of Longing

- Chapter 2 Edwardian Feminism on Tour: International Suffrage Theatre in Australia

- Chapter 3 Dramatic Negotiations: The New Woman, Women’s Colleges, and Cultural Anxiety

- Chapter 4 Katharine Susannah Prichard: Socialist Desire and Suffrage Theatre

- Chapter 5 Stella Miles Franklin: The Suffragette Speaks

- Chapter 6 Inez Bensusan: Activist and Aesthete

- Chapter 7 The Glass Curtain: Suffrage Theatre and Feminist Legacy

- The Burglar (Katharine Susannah Prichard)

- The Apple (Inez Bensusan)

- Somewhere in London (Stella Miles Franklin)

- Bibliography

- Index

The research and writing of this book was made possible by the award of several research grants (thank you to the University of New England, La Trobe University, and Curtin University) and the generosity and encouragement of many, whose gifts ranged from critical engagement and advice to financial and in-kind assistance. I am extremely grateful to the trustees of the State Library of New South Wales for granting permission to publish Somewhere in London, and to the State Library of South Australia for permission to reproduce Thelma Afford’s sketch of her suffragette costume designed for South Australia’s Centenary Pageant of 1936. To Katharine Susannah Prichard’s rights holder, who provided permission to publish the manuscript of ‘The Burglar’, and the National Library of Australia for facilitating this, I am gratefully indebted. I extend special thanks to James Bradley, Georgina Siri, Julian Croft, Viv Gardner, Julie Holledge, Veronica Kelly, Jackie Kramer, Matthias Pfisterer, Susan Croft, Carl Bridge, Brian Flanagan, and Diana Mastrodomenico. Angela John and Katherine Kelly kindly shared information, and the late Doris Mardie Smith assisted in the transcription of material. It was a pleasure to work with theatre historian colleagues Elizabeth Schafer and Carolyn Pickett on other histories of women and theatre. The Australasian Drama Studies Association enabled me to test through publication and conferences many of the arguments contained in this book. Many institutions have given kindly of their time, including the Imperial War Museum, Melbourne University’s Janet Clarke Hall, and Berkelouw Antiquarian Bookdealers. The staff of Sydney’s Mitchell Library, London’s Fawcett Library, the Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection, and the Australian Jewish Historical Society were particularly helpful, as was Dr Anthony Joseph from the Jewish Historical Association of England, and Dr Rosemary Annable from Sydney University Women’s College. Sincere thanks to the late Jill Croxford and her son Robert Appleby – relatives of Inez Bensusan – for their reminiscences, permissions and ←xi | xii→delightful company. When a book takes a quarter of a century to write, it goes without saying that I am thankful to my publisher and editors for their patience, commitment, and belief: thank you Christabel Scaife for your original commission and Laurel Plapp for all else, and all of you for that most suffragette of lessons, the value of holding one’s nerve.

Libraries and special collections

AJHS |

Australian Jewish Historical Society |

ANL |

Australian National Library, Australian Capital Territory |

BAT |

Battye Library, Western Australia |

BL |

British Library, London |

CHC |

Campbell Howard Collection, New South Wales |

FAL |

Fales Library, New York |

FAW |

Fawcett Library, Landor |

FL |

Fisher Library, New South Wales |

FP:ML |

Miles Franklin Papers: Mitchell Library |

JCH |

Janet Clarke Hall Archives, Victoria |

LTL |

La Trobe Library, Victoria |

LON |

Museum of London Library, London |

ML |

Mitchell Library, New South Wales |

MM |

Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection, London |

MOR |

Mortlock Library, South Australia |

MU |

Melbourne University Archives |

PACSA |

Performing Arts Collection of South Australia |

SUWC |

Sydney University Women’s College Archives, New South Wales |

Organisations

AFL |

Actresses’ Franchise League |

ANZAC |

Australia and New Zealand Army Corps |

ANZWV |

Australia and New Zealand Women Voters |

AJHS |

Australian Jewish Historical Society |

BJHA |

British Jewish Historical Association |

BRADC |

British Rhine Army Dramatic Company |

FHC |

State Library of New South Wales Family History Centre |

JLWS |

Jewish League for Woman Suffrage |

JTL |

Jewish Theatre League |

NAACP |

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People |

NWTUL |

National Women’s Trade Union League |

SUDS |

Sydney University Dramatic Society |

WCTU |

Women’s Christian Temperance Union |

WSPU |

Women’s Social and Political Union |

WWSL |

Women Writer’s Suffrage League |

Suffrage Theatre and the Women’s Movement: A Short History of Longing

The sheer hubris of women thinking they can change the world through creative protest and rational appeal: this defines the character and will of the suffrage theatre movement. Women fighting for suffrage fought differently than men, and their protest against inequality ranged from using their creative wiles to outright violence. When rational appeals failed, an intelligent plot device in a narrative writ to help secure female suffrage was enacted: the use of theatre to win hearts and minds over to the cause. Activists for women’s suffrage have been reified, films have been made, histories written, centenaries celebrated – but these obvious accounts do not necessarily reflect the genuine complexity of women’s relationships – as audience and artists – to political life. Theatre – with its distinctive contribution to achieving the vote for women – offers us unique sociological insights into that complex world of women and desires in what was otherwise a most unromantic era. What our suffrage heroines achieved in the early part of the twentieth century has become almost apocryphal if we are to believe that they were singular and exceptional women. This history of suffrage theatre firstly argues for the ensemble nature of the radical change that was achieved during the suffrage era (perfectly exemplified by theatrical adventurism), and secondly for the unique contribution of Australian women dramatists to those achievements.

Considering the history of women, bohemianism, and political activism, the twentieth century offers blatant examples from the suffrage movement to the explosive days of Paris in 1968, and the longest and most famous protest in feminist history, the Greenham Common Peace camp in England against nuclear proliferation from 1981 to 2000. Like all great movements, these examples were ensemble acts. While A Splendid Adventure has its leading characters (Inez Bensusan, Stella Miles Franklin, ←1 | 2→Katharine Susannah Prichard, among others), its key scenes and locations (women’s colleges, little theatres in Australia and Chicago, London in its entirety including even the sky above, if we count Muriel Matters and her ballooning campaign), as well as its core themes (cultural expatriation, feminist desire, theatre as protest), as a history this book makes no claim for reification of any individual or moment. To do so would belie the suffrage era and its hallmarks of conflicting passions and often oppositional desires – which the First World War threw into stark relief.

A Splendid Adventure is therefore a group biography of an assorted collection of Australian women theatre makers. The suffrage era was a messy time, especially for women. Suffrage dramatists were not united by being for something, but rather by being against something: inequality. As heroines for twenty-first-century citizens, they can be confounding women to admire. For example, they had a habit of relying on cocaine to keep up their busy schedules, and often eschewed relationships (conventional or otherwise) to devote themselves wholly to the cause: this does not necessarily offer a mentoring blueprint for contemporary women still seeking equality today in precarious times with arguably greater demands on their ‘postfeminist’ time. What did women really want during the suffrage era, and what better place than the theatre to perform, mark and dignify with attention this complex question, and explore the historical longings of women?

Why theatre?

‘I have always held out that drama should carry an ethical message as well as entertain. It should be one of the greatest modern influences for good.’ So said Avis the famous actress, a character in Miles Franklin’s play The Survivors, written in 1908. Avis was lamenting the sad state of American drama of the day, which she thought was full of ‘pornographic balderdash for the edification of moneyed degenerates’.1 Franklin wrote this play in ←2 | 3→Chicago where it was intended for the commercial stage. Her fictional actress – who was also a socialist and suffragist – neatly expresses the sentiments of suffrage theatre practitioners like Franklin who used the stage for the ‘good influence’ they hoped to achieve. Through such dramatic negotiations, Australian women writing for the stage in the suffrage era sought to fulfil their political and social ambitions. More, they chose the theatre as a stage to enact their dearest-held desires.

Australian suffrage dramatists were devoted to the stage as the singular most exciting cultural space to consider democracy in the contemporary world. Their take on this was unique because they were enfranchised women – and as a creative professional class largely expatriates – in a world where votes for women were not normal. To advance their careers they embraced the global economy and in so doing they simultaneously shed the status and equality they had been afforded at home. A Splendid Adventure is devoted to exploring what that specialness meant for international feminist creative practice, and argues for the distinctiveness of the contribution of Australian suffrage drama.

Perhaps the best test for these claims is to consider the present: what is it like to be a woman playwright in the Australia of the twentieth-first century, more than a century post-suffrage? In ‘The National Voice 2017’, a survey of Australia’s 10 largest theatre companies, it was indicated that their seasons included 95 plays, of which 52 (55 per cent) were written by an Australian playwright. This was an almost 50 per cent increase since 2016, and a direct response to advocacy. Whilst good for Australian theatre in general, however, only 23 (44 per cent) were written by a female playwright, a number slightly higher than that recorded in 2016 (39 per cent) and 2015 (43 per cent). Australian voices being programmed on national stages is of course vital for a sustainable creative industry, more so if that programming reflects original and new drama, which women suffrage dramatists were keenly focused on. Is their political legacy real, and did it contribute to contemporary thinking around sustaining viable creative practices for today’s women playwrights? A 2018 report for example noted ‘a disconnect between Australia’s rich theatre history and a continued life for these works on the stage’, but the Australian Writers Guild remains ‘cautiously optimistic’ as it has a long-stated goal to achieve gender parity ←3 | 4→in programming across Australian-written seasons. In surveying gender parity, ’The National Voice’ found in 2018 that 62 per cent of plays were by an Australian female playwright, and that all major companies had achieved parity goals.

How does this compare with professional opportunities for women playwrights in the America and England of today, and is it better or worse than a century ago? At the beginning of the twentieth century, America and England were the two most important destinations for economic and cultural women expatriates during the suffrage era. America, whose theatre and politics Miles Franklin had satirised as being characterised by the need to satisfy the ‘edification of moneyed degenerates’ had nevertheless represented enormous promise for her as a female playwright. But Franklin might not have felt so enthusiastic a century later. A story as parable: in early twenty-first-century New York a play called The Butterfly Collection by Theresa Rebeck was produced amidst an atmosphere of high artistic and critical excitement and expectation: it was promising to be a big theatrical deal. This is what happened next: after the New York Times published a negative review – dismissing the play as feminist diatribe, accusing the playwright of having a man-hating agenda, and expressing sympathy to the director for having to work with someone as ‘hideous’ as Rebeck – the play closed. People were shocked. There was community outcry. Apologies were made behind the scenes. One supporter went to the Dramatists Guild Council, read the review aloud, and declared that if the reviewer had dared to write such bigotry that was, for example, racist or homophobic rather than sexist then the review would never have been published. But the play remained closed, the interest of commercial and regional theatres evaporated as did that of the American Theatre Magazine to publish it, and to this day the play – the playwright’s best, some argue – has not enjoyed its original promise, rudely debunked. Rebeck was given all kinds of well-intentioned advice about how to handle the misogyny, ranging from producing her plays under a male pseudonym, to in effect reforming her feminist identity to make it ‘acceptable’. Other things happened: Rebeck was told that it was a sign, that she and her work were not welcome in New York; close friends screamed at her; her agent suggested she write a novel (and told her, after deciding that her next two plays were ←4 | 5→‘un-producible, that he could no longer represent her). Rebeck, by her own account, ‘fell off the map’ and became depressed – until one day when she was told she should go to a theatre laboratory called The Lark. She did, and according to Rebeck it saved her sanity and career – ‘There is no organisation, in my mind, that does more’.2

A century earlier, women suffrage playwrights would have fully empathised with Rebeck’s plight, and also that of the need for the industry scrutineering and reform that has been recently conducted in contemporary Australia, because they themselves were fully aware of the ‘Glass Curtain’ discriminating against women playwrights during the suffrage era. But would they have believed or credited that their plight would also be that of women playwrights 100 years hence? As Rebeck regrettably pointed out using the year 2007 as an example, she was the only woman to open a play on Broadway, in a year that nationwide in the USA recorded that only 12 per cent of new plays produced were written by women. Likewise, in England Sir David Hare has recently been quoted in the press as saying that ‘many of today’s best plays were being written by women, but that “macho” theatre companies were failing to capitalize on them’.3

Theatre history offers pockets of positivity for women dramatists – for example in London, between 1695 and 1706, it has been estimated that women wrote between a third and a half of all produced plays. A Splendid Adventure explores another such period in history – the suffrage era – that saw women playwrights negotiating their world and lives on the stage in a prolific manner. This is, particularly, a story of those pioneering Australian women playwright participants. The answer to the question of why the theatre industry is still in need of feminist reform perhaps partially lies in the lack of awareness of women’s historical achievements in theatre, without which that legacy does little to inform or instruct current cultural industry practice and knowledge.

←5 | 6→This begs the question, how valuable is feminist theatre historiography in terms of the experience economy produced by the cultural industries? Invaluable, if we are to consider a story told by Australian playwright Mona Brand. Brand is best known as a communist dramatist largely for her work with the New Theatre movement.4 She tells of how Melbourne’s New Theatre, having outgrown its premises, located and secured a new building in an old pram factory in the inner city and promptly began using it as a theatre space. This space in fact went on to become the iconic Pram Factory and Australian Performing Group (born in the late 1960s/early 1970s), historically and widely credited with revitalising if not creating contemporary Australian drama as we know it today. As Brand’s story reveals, the APG were originally invited, in a comradery fashion, to share the space. They colonised first the front of the building, shunting their hosts to the back theatre, which they also annexed, then finally repeated this with the downstairs theatre space. The APG – a famous bastion of masculinity – effectively evicted the New Theatre – a women’s creative stronghold – from their own premises. As historian Michelle Arrow comments, this story operates as a telling metaphor for how Australian theatre historiography had long silenced the robust and rich tradition of women and theatre, women who had ‘fought gamely for spaces in which to tell their stories’ and with marked success, only to be forgotten in the haste and appetite for new voices, represented by what theatre historian John McCallum has called a ‘parvenu of young men’ because, in Arrow’s words, our ‘theatre was firmly yoked to an emergent, aggressive nationalism in the 1970s’. Arrow rightly names this forgetting a process of dismissal, one which generates a ‘control over the stories of Australia’s cultural past’.5 Those pre-1970s stories are needed in the twenty-first century more than ever.

Feminist theatre historiography is also invaluable in the sense that Naomi Paxton reveals in her history of the Actresses’ Franchise League, ←6 | 7→Stage Rights!: to understand the history of women and theatre during the suffrage era is to recognise that the work of these women ‘was designed to both work with and challenge the institutionalized sexism pervading the industry as a whole, harnessing the energy, ambition and imagination of the League’s membership and creating new opportunities for women in the performing arts that would have far-reaching consequences’. Paxton’s work renews interest in and underscores the value of feminist theatre scholarship to the history of the suffrage era, particularly with her fresh argument for the ‘intersections between performance, representation and visibility of suffragists’6 and the inspiration for change this created both in public and private spheres.

Secrets are often viewed as a currency of power. If memory is recognised as vital to the recovery of secrets, then feminist history relies on suffrage historiography and its recovery of memory to redress powerful ideas of women that contribute to ongoing discrimination. The sharing of that history – the recovery of the story of suffrage dramatists – is all important in creating brand-new relationships to knowledge and power. Peggy Phelan is interested in theatre’s ‘intimate relationship with the secret’, and how intelligence is created through that power. As Phelan says, ‘For the critic to return to the performance is to restage and represent the drama of meaning’s constellation and evaporation’. When historians try and locate secrets about the past – seeking their own and other’s empowerment – they are frustrated by the triple jeopardy of ‘meaning’, and its ‘constellation’ and ‘evaporation’. These elements, which also comprise performance (and eventually become theatre history), mirror the triad of birth, life, and death. History is concerned with what lies beyond that ominous cycle: the memory of what once was. It is memory which provides the only counter, and it is the quest for memory and the sharing of ‘secrets’ that occupies theatre historians. Bearing in mind that the pursuit of memory and its subsequent sharing creates new constellations of meaning, this book is particularly interested in the mysteries of Australian suffrage theatre history. It offers a story of the dramatic negotiations conducted by Australian ←7 | 8→feminist playwrights, who brokered many secrets in their own quest for power during the suffrage era.

Singular distinctions

Australian suffrage theatre is vastly different from its British and American counterparts, but its extraordinary contribution to the development of early feminist theatre has been underestimated and overlooked in both Australian and international feminist theatre histories. This book, however, is not meant to be a parable of disinheritance. It would be false to suggest that the traditions of women’s theatre in Australia have not been felt by at least some members of feminist and theatre communities. Those traditions are indeed in operation, with the memory of feminist history creating its own contemporary rhythm. Nevertheless, the pulse of that legacy has been misread and mistaken by theatre practitioners and historians alike. Hence this book – skeletally, at least – is intent on redressing absences. A critical scrutiny has guided this process, exploring the processes of disappearance.

Due to the volume and quality of empirical evidence that presented itself, this history is inevitably ‘a series of swift glides over very thin ice’, a term employed by one of Australia’s pioneer women’s historians, Beverley Kingston.7 She was apologising for not including a chapter on prostitution in her groundbreaking history on women and work in Australia. Kingston’s own research revealed that there was far more to be written about than could be accomplished in one volume, and she hoped that in time her book would be nothing more ‘than a quaint and primitive document, colonial in origin, and rather behind the times’.8 Research for A Splendid Adventure began with the notion that there should be an Australian suffrage theatre, ←8 | 9→almost expecting it to be disproved, or to find at the most only a few examples. There was in fact a large amount of writing for the theatre created by Australian women during the suffrage period, although not all of it could be classified as feminist or pro-suffrage. Indeed, there are too many examples to give them all justice within one book. As a result, I chose to focus on what was to me the most appealing and also revealing aspect of my research as it presented itself: the expatriate feminist tradition. This allowed a larger historical framework of inquiry, demanding international comparisons to be undertaken both within the area of suffrage history and women’s theatre history more generally. As a foundation for that comparative process, it was essential to understand the political, social, and cultural environments that Australian women were experiencing at home, and subsequently define the distinctive character of their work and what distinguishes Australian suffrage theatre from its British and American counterparts. I define this as possessing three attributes: the post-suffrage attitude of the playwrights, who as Australians were enfranchised women in a largely disenfranchised world; the expatriate impetus which saw so many Australian feminist writers directly responding to the internationalism of the women’s movement of this time; and the influence and adaptation of trends in feminist theatre from abroad.

Much of the evidence used to create the arguments of this book come from play texts. Ellen Donkin argues that ‘in all areas of the theatre … women have made repeated efforts to establish a point of view that is different from men’, and that women’s theatre history has special stories to tell.9 That special difference was expressed most visibly in the redefinitions of female subjectivity conducted by women playwrights – hence my insistence on the value of the text itself for locating hard evidence of feminist interrogations. Although ‘images of women’ may seem an old-fashioned feminist enterprise, the shifting subjectivities of women expressed in the texts of this study reveal enormous amounts about how women negotiated their life positions during the suffrage period. Janelle Reinelt discusses the problems that historians of theatre especially have because of theatre’s ←9 | 10→‘notoriously transient’ qualities. She argues that those very problems of evidence offer a ‘point of entrance for critical theory’ that is actually advantageous in the quest for knowledge:

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 408

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789973242

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789973259

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789973266

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781906165901

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15446

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (September)

- Keywords

- Bradley Smith suffrage theatre women's drama feminist history women's suffrage

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2020. XIV, 408 pp., 70 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG