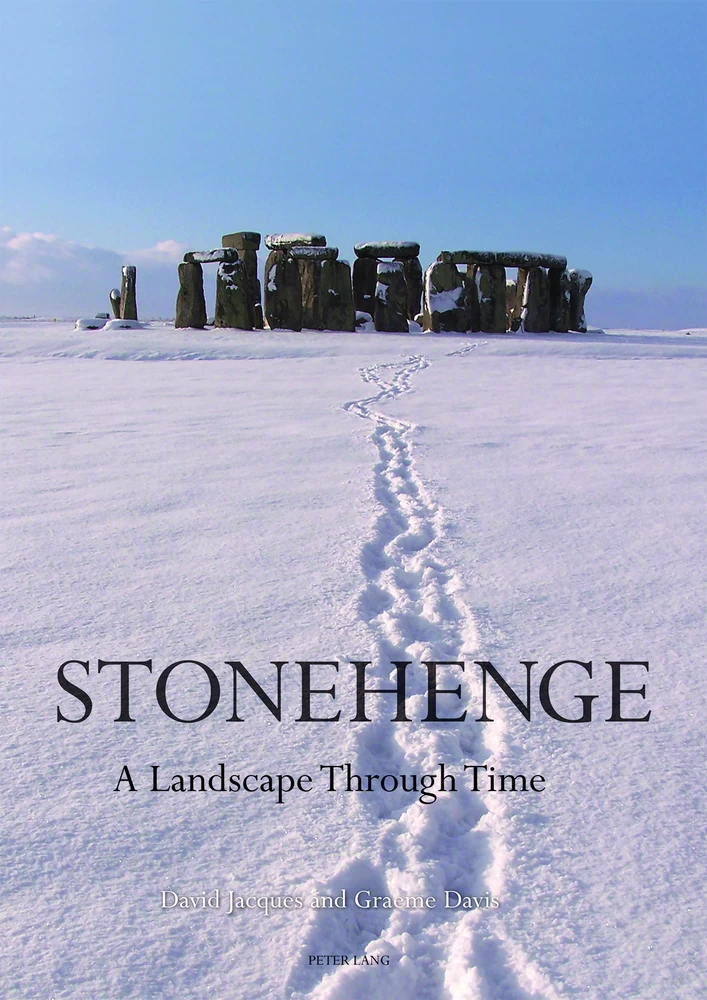

Stonehenge: A Landscape Through Time

Summary

The discovery of the internationally important Mesolithic site at Blick Mead by the University of Buckingham team, with specialist support from Durham and Reading Universities, the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project and the Natural History Museum, provides a rich data set for students interested in the Mesolithic in general and the establishment of the Stonehenge landscape in particular.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Romano-British reactions to the Stonehenge prehistoric landscape: A re-evaluation of settlement patterns and uses of that landscape

- 2 Environmental implications of Neolithic houses

- 3 Towards a methodological framework for identifying the presence of and analysing the child in the archaeological record, using the case of Mesolithic children in post-glacial northern Europe

- 4 The effectiveness of an enhanced grid extraction system within the context of the Blick Mead spring excavations

- 5 An evaluation of the relationship between the distribution of tranchet axes and certain Mesolithic site types along the Salisbury Avon

- 6 An assessment of the evidence for large herbivore movement and hunting strategies within the Stonehenge landscape during the Mesolithic

- Appendix

- Index

FRED WESTMORELAND

Foreword

The first time I spoke to David Jacques he asked me what I would like from the work at Blick Mead. I asked him to fill the gap between the Stonehenge Postholes and the Neolithic. The rest, as they say, is prehistory. Working with a shoestring budget from Amesbury Town Council, Quinetiq and private donors, David’s army of willing volunteers have uncovered one of the most important archaeological sites of the twenty-first century. In the process they have rewritten the history of the Stonehenge landscape and instilled a new pride and new purpose into the Amesbury community.

Having given me the Mesolithic, David has now started to read my mind and to deliver my secret desires. The introduction of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act (1979) and the National Heritage Act (2002) coincided with a period of rapid expansion to the south-east of historic Amesbury. Archaeology has flowed from the ground – the Amesbury Archer is only the best known of the items in a catalogue which includes Roman cemeteries, Henge monuments and (whisper it) Mesolithic postholes.

Developers are required to pay for excavations and reports, but not for the interpretation of those reports and the synthesis which creates history. Local authorities are struggling to deal with the wealth of material deriving from the Portable Antiquities Scheme. They have no mechanism at all for the systematic analysis and evaluation of the reports that accompany artefacts and planning applications. I know that, for Amesbury, there are the products of 30 years of excavation waiting to be examined, 30 years of reports which would transform our understanding of my town’s history and development.

When we set out to create a History Centre for Amesbury it was intended to be a place for study, making available locally the reports on our 5,000-year history. The first step was to get the material, who would interpret it was a bit of a puzzle. Thanks to Blick Mead, those 5,000 years have now turned into 10,000 years, but also thanks to Blick Mead we may have identified a way in which the analysis could be carried out.

The six MA dissertations contained within this volume, starting from within the Stonehenge landscape, create narrative from the raw materials of archaeological investigation. Stepping out of the shadow of Trench 19, the students have set out to tell us what this all means.

Following the ordering of the book, we are invited to consider: Romano-British Amesbury; Neolithic house building practices; the role and lives of children in prehistoric societies; an excavation methodology for dealing with waterlogged deposits; the identification of new sites from the distribution of Mesolithic material, and restrictions on herbivore movement within the landscape. Six studies of six disparate subjects, united only in that they tell me more about my community, my country and my world.

I congratulate the authors of these dissertations. I hope that they have shown the way. I hope that many more will conduct their excavations in the county archives. There are still things I would like to know.

Acknowledgements

We remain extremely grateful to the Cornelius-Reid family, the Antrobus family and Amesbury Abbey residents for allowing us to work on site at Blick Mead and Vespasian’s Camp. We wish to extend deep thanks to local residents Mike and Gilly Clarke, Andy and Becky Rhind Tutt, Pete and Tracey Kinge, Dave Allerton, Tim Roberts, Brian Edwards, Malcolm and Jenny Guilfoyle-Pink and Cllr Fred Westmoreland, Vera and Matt Westmoreland, Richard Crook and Mike and Rosemary Hewitt for all their hard work and keen support. We also wish to heartily thank Peter Rowley-Conwy, Bryony Rogers from the Department of Archaeology at Durham University, Nick Branch of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Reading, David John and Simon Parfitt of the Natural History Museum, Barry Bishop, John Drew and Nick James of the University of Buckingham, Tom Phillips of Oxford Archaeology, Tom Lyons, Vicky Ridgeway, Roy Froom, Mark Bush, Patricia Woodruffe, Craig and Sue Levick and everyone at Amesbury History Centre and Peter Lang for all of their support and work on various Blick Mead data which has benefited this volume. The Amesbury Heritage Trust and Amesbury Archaeology has provided much appreciated financial support to augment the University of Buckingham’s generous endowment to the project and we are very grateful and wish to thank them too.

In particular we acknowledge the crucial contributions of Mike Clarke, without whom there would be no Blick Mead, and Simon Banton, whose encouragement and skill set has done so much for the authors, and whose wonderful picture of Stonehenge graces the cover of this book. The writers and editors wish to thank our families and friends; without their support this book would not have been written.

Professor David Jacques

Professor Graeme Davis

DAVID JACQUES

Introduction

The concept of this book materialised as a result of some brilliant research by University of Buckingham MA Archaeology students in 2014–2015. Each examined a feature of the Stonehenge landscape from a different space and time perspective and produced work which contained a key focus on a neglected aspect of the multiple history of the area. Their dissertations have been edited into chapters and the broad scope of the collection covers people using, building and reshaping this landscape from the end of the Ice Age to the end of the Romano British period. In doing so new detail about the richness and variety of ways generations of ordinary people understood the place is revealed.

The discovery of the internationally important Mesolithic site at Blick Mead by the University of Buckingham team, with specialist support from Durham, Southampton and Reading Universities, the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project and the Natural History Museum, provides a rich data set for students interested in the Mesolithic in general and the establishment of the Stonehenge landscape in particular. Situated just over 2 km east of Stonehenge (NGR SU146417), and visited for nearly 4,000 years in the Mesolithic (7960–4041 cal BC), the most recent excavations have provided further evidence of the communities who built the first monuments at Stonehenge between the ninth and seventh millennia BC, and for Mesolithic use of the area continuing into the late fifth millennium BC and the dawn of the Neolithic period. Thirteen radio carbon dates of the sixth and fifth millennia BC are the only such dates recovered from the Stonehenge landscape and fill a crucial gap in the occupational sequence for the Stonehenge area at this time. Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages and Romano British artefacts found at Blick Mead offer further avenues for research.

The archaeology discovered at Blick Mead has prompted many important new questions about the Stonehenge landscape and some are addressed for the first time in this volume: How did local Romano British communities interact with the prehistoric monuments and earthworks landscape around them, including Stonehenge? What does the monumentalising of the landscape in the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age imply about resource management in the area and beyond? Was the early establishment of the Stonehenge ritual landscape invented by Neolithic farmers from nothing? How can we find the children in the archaeological record? Is there any evidence for the landscape and the Stonehenge knoll itself embodying understandings about the place that could reach back to Mesolithic? Why have spring sites and their resources been neglected for investigation? What sort of excavation methods should we employ when we are digging and recording them?

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 212

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787074804

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787074811

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787074828

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781906165857

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11045

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (March)

- Keywords

- Stonehenge archaeology Blick Mead Mesolithic Neolithic Vespasian’s Camp Roman Romano-British Salisbury Plain

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. XIV, 212 pp., 9 fig. b/w, 17 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG