Reshaping the News

Community, Engagement, and Editors

Summary

Reshaping the News argues for that alternative, deconstructing the reporting and editing relationship and illustrating the ideal version of editorial oversight. Author George Sylvie dissects reporter communities and culture, as well as the connection between journalism and geographic space/management. The book also examines whether journalists have developed the appropriate infrastructure to assure credibility and avoid potential mishaps, misconduct, and misrepresentation. Though the innovative, non-traditional approach to audience engagement outlined within challenges journalistic boundaries, Reshaping the News posits its new model as necessary and of potential lasting value to the field of journalism.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance Praise for Reshaping the News

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- About the Author

- Preface: New Maps (Maxwell McCombs)

- Community

- New Definitions of News

- New Newsroom Structures

- Summary

- Setting

- Notes

- Part I. Where We Are

- Chapter 1. The Dilemma of Newsroom Management

- Evolution Is Hard

- The Path for Newsrooms

- Handling That Fork in the Path

- Why Now?

- Notes

- Chapter 2. Understanding News, Geopolitics, and Editing

- Newspaper News: Nature, Tradition and Change Implications

- Community, Place, and Politics: The Missing Pieces

- Keeping Up with the Community

- The Not-Really-Learning Newsroom

- Notes

- Chapter 3. The Big Fail

- The Disintegration of Directing

- The Double-Edged Sword of Faulty Professionalism

- Divisive Diversity

- The Road Ahead

- Notes

- Part II. Why We Should Have Left

- Chapter 4. The Costs of Knowledge

- Beekeepers and Beats

- Beating a Path to the Superhighway’s Entrance Ramp

- Beating a Brick Wall to Get the Margarita

- The Light at the End of the Tunnel

- Notes

- Chapter 5. Fallacies and the Future of Audience Engagement

- Samples, Stars and Snags in Newsrooms’ “Understanding”

- The Ultimate Snag: Newsrooms’ “Understanding”

- A Structural Way Forward

- Notes

- Part III. Where We Need to Go

- Chapter 6. Where No Journalist Has Gone

- Reshaping the News

- Community Interests and Reshaping the News

- The Audacity of Leading

- Notes

- Chapter 7. Conclusion and a Beginning

- The Invisible Editor

- A “Theory” of the Editor

- Notes

- Index

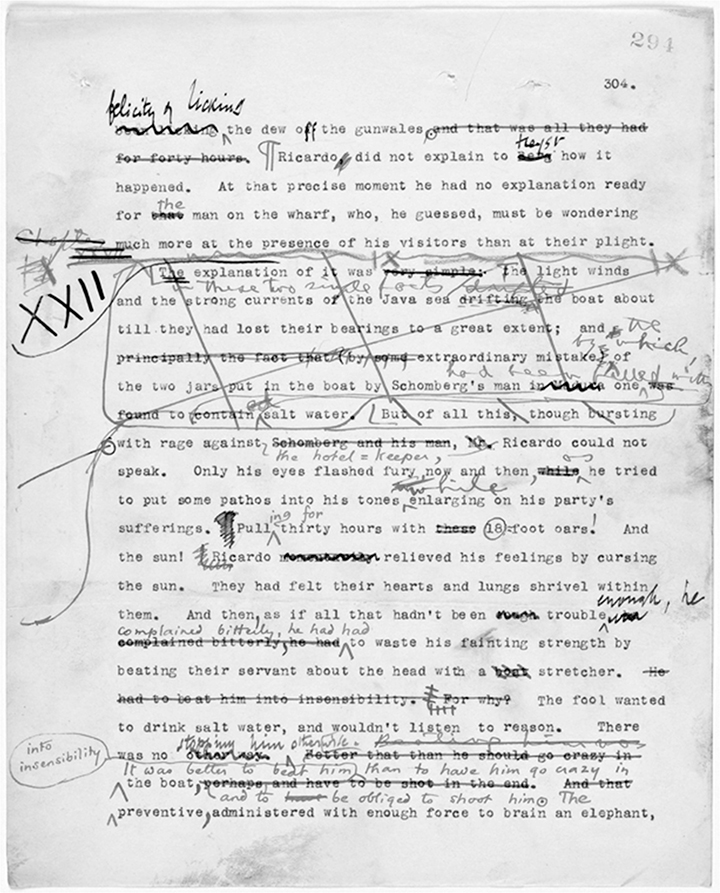

This book is illustrated with public domain figures from The New York Public Library.

Figure 0.1: “Victory, p. 304.”

Figure 1.1: “The Editors.”

Figure 2.1: “Portrait of Frederick Douglass seated at desk holding newspaper from Harper’s Weekly.”

Figure 3.1: “Mrs. E. J. Nicholson.”

Figure 4.1: “Mattie Allison Henderson.”

Figure 5.1: “Joseph A. Medill.”

Figure 6.1: “William Randolph Hearst.”

Figure 7.1: “Joseph Pulitzer.”

George Sylvie earned his Ph.D. from and is Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. He studies newspaper innovation and decision-making, and his work spotlights editors, value systems, management style, online markets, diversity, and reporting. He has authored books on reporting, media management, and decision-making.

Drawing new maps for congressional districts following each decennial census is a well-known political exercise as political parties seek to extend their reach and impact. In today’s rapidly changing communication landscape and the evolving nature of the communities they serve, newspapers also need new maps to navigate this changing terrain.

How many newspapers have ever drawn a detailed map of their circulation area, much less refined that map as the communities they serve undergo change? A newspaper’s coverage area includes a wide variety of communities that vary along many dimensions. Information on many of the obvious dimensions—variations in income, home ownership, level of education, and median age, for example—are available in minute detail from the decennial census. And many other sources can be tapped to gain a comprehensive understanding of how to adjust to the changing world in which newspapers and journalists work. Using these data and advanced statistical techniques, just as the political parties do to extend their reach, newspapers can construct precise maps identifying the boundaries of these communities and neighborhoods, down to the block level. And these maps can lay the foundation for a fresh approach to journalism.

From these maps can emerge strategic plans to extend a newspaper’s reach through explicit knowledge of the various communities served or unserved, ← x | xi → the kinds of news that these communities will find relevant, and the kind of newsroom structure needed to produce this news. Through its detailed exploration of these three facets of journalism—community, new and expanded definitions of news, and newsroom structure—Reshaping the News enables editors to proactively confront their changing environment.

Community

A focus on the variety of communities that compose a newspaper’s coverage area can produce a new mindset. And as most cities and towns expand and fragment beyond the core city, it becomes important to find communities of interest across the geographic landscape, to not stay locked into fixed locations as sources of news. Where news occurs and to whom that news is relevant constantly shift. Change is the contemporary keyword for the environment in which journalism operates.

A recent news story from my hometown, Birmingham, Alabama, referred to an upscale suburban mall catering to Latino residents. To paraphrase an old automobile advertising slogan, “This is not your father’s Birmingham.” Community no longer means the neighborhoods of the past. Community is now defined in much more complex ways, and the mix of characteristics defining these communities is continually changing.

Chapter Two notes that it would help to spend more time thinking about community concerns—because this can reveal more practical advice on editing a newspaper—than to simply follow traditional routines. Across many chapters, Reshaping the News presents an innovative, non-traditional and alternative approach to audience engagement that challenges the boundaries, enlarges the vocabulary of journalism, and represents a new characterisation of news.

New Definitions of News

Understanding in detail the various communities in your circulation area can be the first step toward a precise redefinition of news that is highly relevant to current readers and to potential readers. Reshaping the News refers to this as getting the public invested in the news and, as an example, asks this question: “Would you [as a reader or potential reader] rather that the newspaper’s education reporter spend most of her time covering the divided politics, name-calling, and bureaucratic-driven actions of the school board or would you like her ← xi | xii → to help you figure out what teachers are doing in the classroom or see your child’s test answers?”

Doing away with the one-way journalism of covering meetings or every action of public officials means broadening the news to include more personal interests of the public. In other words: Use your detailed knowledge of the communities you serve and their contemporary dynamics to make bottom-up news a key element of coverage. This strategy also can include working closely with different public interest groups who can contribute information and perspectives that the newspaper can convert to even more relevant digital experiences. Reshaping the News details a model of active, systematic, and detailed monitoring of community interests and movements with an eye toward reclassifying, stretching, refitting and broadening what constitutes news. Most importantly, this strategy can identify aspects of communities that are potential sources of growth for news organizations.

New Newsroom Structures

Closer attention to communities and redefining news to match their interests imply significant changes in the way that newsrooms are organized. To effectively reach the communities served by your newspaper with broader definitions of what constitutes relevant news, means positioning resources to deploy reporters in new, substantial and logistical observation posts in the community, building stronger and new alliances with previously uncovered groups (particularly minorities), developing and refining the use of multiple methods of communication, and above all, nourishing and rewarding journalistic appetite for continued change in this ever-changing cultural and communication environment.

One example of a shift in the focus of news and how news is gathered involves a change from the heavy reliance on the traditional news beat structure to an ongoing creative look at what is newsworthy in terms of topics. In many instances, this means reporting that cuts across several traditional beats and often means covering situations that are not covered at all by traditional beats. In other words, covering topics being discussed in neighborhoods, but which have not yet surfaced on any of the traditional beats. In this regard, a new beat to determine what are the salient topics of the day could be systematically monitoring neighborhood list serves or hanging out at neighborhood coffee bars, barber shops and other places where people gather. ← xii | xiii →

Summary

To be successful, these new approaches to understanding the communities in your circulation area and the creation of a broader definition of news relevant to these communities, require a new mindset among journalists, one that emphasizes creativity and innovation. How to structure, encourage and reward this creativity and innovation may be the most daunting task of all for editors. Reshaping the News opens a thoughtful discussion on how to transform the editor from manager to leader who encourages new newsgathering routines, experimentation, and learning.

Figure 0.1: Victory. Typescript (incomplete) of novel, with the author’s and unknown editor’s manuscript corrections (above).1 ← xiv | xv →

In September 2008, my University of Texas at Austin School of Journalism colleague and friend Iris Chyi and I started preparing a presentation for a meeting the following March of a global group of media management and economics researchers in Miami. We had obtained a consulting firm’s data about newspapers’ online audiences that initially blew our minds: More than a quarter of the people who used a typical newspaper’s web site lived nowhere near that paper’s city of origin.2 This statistic raised the question of why so many existed, as well as made us wonder why anyone would want to read a local newspaper from a place where they didn’t live. What could they possibly hope to learn or discover?

The answer, of course, resided in these readers’ curiosity—for practical or entertainment reasons—about things happening several miles away. The elephant in the room was the size of that audience and the potential monetary bonanza those readers posed for newspapers, particularly when even then newspapers started to experience readership declines. As always, nothing ever came easy in understanding the newspaper industry.

At the time, newspapers still counted heavily on local advertisers for their revenue.3 That meant newspaper advertising staffs mostly concentrated on generating money from local businesses—largely because that’s the same ← xv | xvi → strategy that they’d always followed. As a result, newspaper staffs knew little about such “long-distance” audiences, as we called them, nor about the advertisers possibly willing to pay for the newspaper’s ability to reach those audiences. In other words, long-distance audiences constituted largesse, or “extra gravy on the pork chop” that newspapers delivered to advertisers. So although newspapers were unwittingly creating information that many long-distance (LD) consumers valued, nobody at those newspapers tried to take advantage of the situation. Iris and I had known that these LD audiences existed from the time newspapers created their web sites, but we had no way to measure and examine them until we could get more complete and valid data—meaning that we couldn’t advise the industry whether such readers formed a viable market. With the consulting firm’s data, we saw ourselves as finally able to help the industry. Or so we thought.

Our study found that more than 60 percent of LD audiences were former or nearby residents—they lived close to but not in the paper’s primary local market. An additional 15 percent had relatives or friends in the primary market.4 Bingo!—something newspapers should pursue, to help pay for the new bills they incurred by going online (and deciding early in the process to give away the content for free). It might take a little work—to figure out exactly how LD-users viewed and consumed the newspaper—by why not? As usual, it’s a bit more complex than that, as we should have known from Iris’ earlier work5 that showed most online content replicated what’s already in the printed newspaper—making the online version a harder sell.

Details

- Pages

- XXIV, 188

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433143403

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433143410

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433143427

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433143434

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14403

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (December)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XXIV, 188 pp. 8 b/w ills.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG