Against Repression

Surrealism, Sublimation and the Recuperation of Desire

Summary

The book reveals how a more transgressive strand of Surrealist art and thought emerged in France in this period, a strand that is underpinned by an increasing openness to sexual alterity. Surrealist works from this time are considered in terms of their more subversive aspect and shown not only to validate erotic desire but also to challenge the certainties (socio-political, personal) of their audience. Surrealist art and literature are thus presented as actively countering the repressive effects of a socially conservative France, aspiring not only to be at the vanguard of social change but of a change of consciousness in society.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- A Note on the Translations

- Introduction. Sublimation/Desublimation: A Question of Definition

- Chapter 1. Tel Quel Critiques of Surrealism: Idealist, Sublimatory and Repressive

- Chapter 2. The Breton-Bataille Polemic Revisited

- Chapter 3. Breton’s Non-Repressive View of Sublimation and Art

- Chapter 4. Surrealism’s Inner Alchemy: Perturbing the Senses, Awakening the Spirit

- Chapter 5. The Surrealist Cult of Love: Extolling the Forbidden Fruit

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Against Repression

Surrealism, Sublimation and the

Recuperation of Desire

Klem James

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • New York • Wien

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National-bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: James, Klem, 1978- author.

Title: Against repression : Surrealism, sublimation and the recuperation of desire / Klem James.

Description: New York : Peter Lang, 2019. | Series: Art and thought = Art et pensée | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018008714 | ISBN 9781787077690 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Surrealism--France. | Surrealism (Literature)--France. | Sublimation (Psychology) | Avant-garde (Aesthetics)--France--History--20th century. | Arts and society--France--History--20th century.

Classification: LCC NX456.5.S8 J35 2018 | DDC 700/.41163--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008714

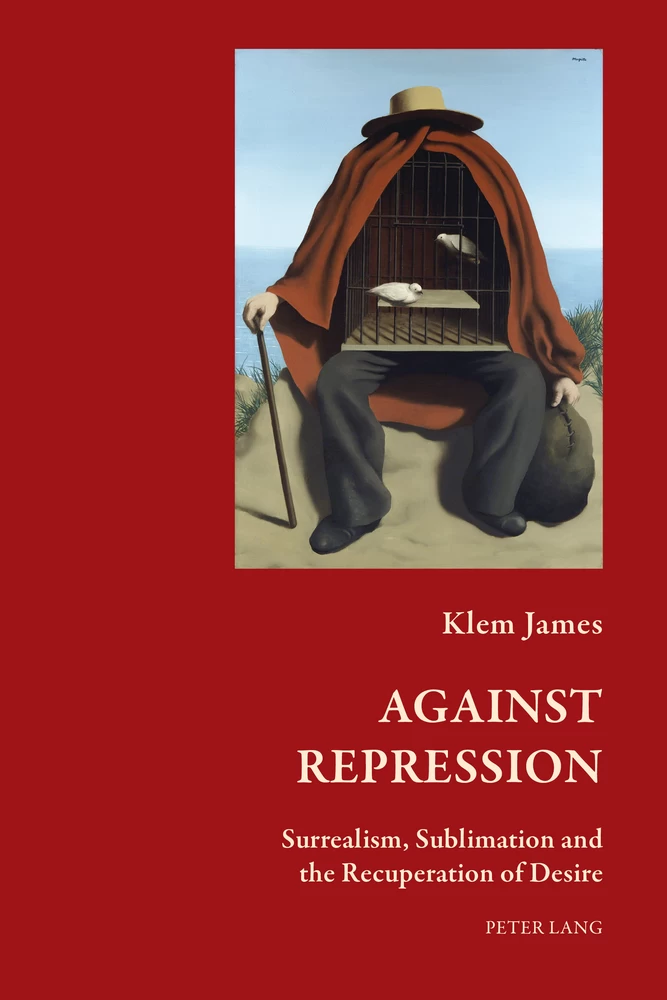

Cover image: René Magritte, Le Therapeute 1937 © Rene Magritte/ADAGP Magritte, Miro, Chagall. Copyright Agency, 2018.

ISBN 2296-1151

ISBN 978-1-78707-769-0 (print) • ISBN 978-1-78707-770-6 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-78707-771-3 (ePub) • ISBN 978-1-78707-772-03 (mobi)

© Peter Lang AG 2019

Published by Peter Lang Ltd, International Academic Publishers,

52 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LU, United Kingdom

oxford@peterlang.com, www.peterlang.com

Klem James has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution.

This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Klem James is Lecturer in French at the University of Wollongong, Australia. He holds a doctorate in French from the University of Manchester (UK) and was previously Lecturer and then Convenor of French at the University of New England (Australia). His research focuses on Surrealism, concentrating specifically on the intersections of psychoanalysis and Surrealism and the use of scientific (and pseudo-scientific) notions within the movement.

About the book

Surrealism has been criticised for having been too steeped in idealism and poetry to have been an effective force for political and personal emancipation in the early twentieth century. The movement, its detractors claim, was conservative in outlook, denying the sexual and material poles of existence, and preferring sublimation over the direct expression of (and engagement with) base desire. These arguments are carefully re-examined and re-evaluated in this book, which focuses on the movement’s artistic and political activities of the late 1930s, 1940s and beyond.

The book reveals how a more transgressive strand of Surrealist art and thought emerged in France in this period, a strand that is underpinned by an increasing openness to sexual alterity. Surrealist works from this time are considered in terms of their more subversive aspect and shown not only to validate erotic desire but also to challenge the certainties (socio-political, personal) of their audience. Surrealist art and literature are thus presented as actively countering the repressive effects of a socially conservative France, aspiring not only to be at the vanguard of social change but of a change of consciousness in society.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

Sublimation/Desublimation: A Question of Definition

Tel Quel Critiques of Surrealism: Idealist, Sublimatory and Repressive

The Breton-Bataille Polemic Revisited

Breton’s Non-Repressive View of Sublimation and Art

Surrealism’s Inner Alchemy: Perturbing the Senses, Awakening the Spirit

The Surrealist Cult of Love: Extolling the Forbidden Fruit

Index←v | vi→ ←vi | vii→

Figure 0.1: Selection of Surrealist artwork (l. to r.): René Magritte, The Titanic Days (1930) © René Magritte/ADAGP Magritte, Miro, Chagall. Copyright Agency, 2018. Hans Bellmer, Untitled, from La Poupée (The Doll) (1936) © Hans Bellmer/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018. Salvador Dalí, Scatalogical OR Surrealist Object Functioning Symbolically (The Surrealist Shoe – Gala’s shoe) – photo of object (1931) © Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dali/VEGAP. Copyright Agency, 2018. Meret Oppenheim, Luncheon in Fur (Also known as: Breakfast in Fur) – photo of object (1936) © Meret Oppenheim/Pro Litteris. Copyright Agency, 2018. Salvador Dalí, Young Virgin Auto-Sodomized by the Horns of Her Own Chastity (1954) © Salvador Dali, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dali/VEGAP. Copyright Agency, 2018. 1

Figure 2.1: Taxonomy of ‘Perversions’ or Sexual Paresthesias as reproduced in Maurice Heine’s ‘Note sur un Classement Psycho-Biologique des Paresthésies sexuelles’. 72

Figure 2.2: Alberto Giacometti, Boule Suspendue (Suspended Ball) (1930–1931) – photo of sculpture © Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti/Copyright Agency, 2018. ←vii | viii→

Figure 2.3: Hans Bellmer, ‘Variations sur le montagne d’une mineure articulée’, Minotaure (1934–1935) © Hans Bellmer/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 2.4: Pablo Picasso, ‘Le Plumeau et la Corne’ (The Feather Duster and the Bull’s Horn) in Minotaure 1 (1933) – photo of sculpture © Succession Picasso/Succession Picasso. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 3.1: Marcuse’s model of sublimation and desublimation as applied to the interrelationship between art and society in The Aesthetic Dimension (1979).

Figure 3.2: Roberto-Sebastian Matta Echaurren, L’Octrui (1947) © Roberto-Sebastian Matta Echaurren/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 3.3: Roberto-Sebastian Matta Echaurren, Science, conscience et patience du Vitreur (Science, Conscience and Patience of the Glazier) (1944) © Roberto-Sebastian Matta Echaurren/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 3.4: André Masson, La Métamorphose des Amants (The Metamorphosis of Lovers) (1938) © Andre Masson/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 3.5: Vincent Van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889).

Figure 4.1: Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1503 and 1515.

Figure 4.2: Symbols of birth and transformation (two aspects of Phanes, the hermaphroditic deity). (Left) Phanes,←viii | ix→ the hermaphroditic deity entwined with a serpent and (Right) the Orphic (or Cosmic) egg from whence Phanes hatched (Jacob Bryant, 1774).

Figure 4.3: Hieronymus Bosch, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, triptych, 1505.

Figure 4.4: Hieronymus Bosch, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, panel.

Figure 4.5: Max Ernst, ‘Chaque émeute sanglante la fera vivre pleine de grâce et de vérité’ (‘Each bloody riot will help her to live in grace and truth’). Illustration from collage novel La Femme 100 Têtes (1929) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 4.6: Max Ernst, ‘Rome’. Illustration from collage novel La Femme 100 Têtes (1929) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 4.7: Max Ernst, ‘images (untitled)’. Illustrations from Chapter 1 (Sunday – Mud) of collage novel Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 4.8: Max Ernst, ‘image (untitled)’. Illustration from Chapter 7 (Saturday – Desire or the great one times one) of collage novel Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 4.9: Max Ernst, ‘image (untitled)’. Illustration from Chapter 3 (Tuesday – Fire) of Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018. ←ix | x→

Figure 4.10: Max Ernst, ‘image (untitled)’. Illustration from Chapter 4 (Wednesday – Blood) of Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 4.11: Max Ernst, ‘image (untitled)’. Illustration from Chapter 5 (Thursday – Blackness) of Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 4.12: Max Ernst, Les Hommes N’en Sauront Rien (Men Shall Know Nothing of This) (1923) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 4.13: Juan de Valdés Leal, Finis Gloriae Mundi (End of the World’s Glory) (1660).

Figure 4.14: Illustrations of Flamel’s Exposition of the Hieroglyphical Figures, reproduced in Robert Desnos’ article ‘Le Mystère d’Abraham Juif’ (Documents, 1925).

Figure 4.15: Robert Fludd, The Day and Night of the Microcosm (1617–1619), reproduced in Grillot de Givry’s Le Musée des Sorciers, Mages et Alchimistes (1929).

Figure 4.16: Images from Gichtel’s Theosophia Practica (1736), reproduced in Documents, no. 2 (1929).

Figure 4.17: Max Ernst, The Robing of the Bride (1940) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018 and, right, an illustration with a similar motif, Max Ernst ‘Loplop et la Belle Jardinière’ (‘Loplop and the Beautiful Gardener’). Illustration from collage←x | xi→ novel La Femme 100 Têtes (1929) © Max Ernst/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 5.1: Man Ray, Photo of wooden spoon in the novel Nadja by André Breton (1928) © MAN RAY TRUST/ADAGP. Copyright Agency, 2018.

Figure 5.2: Allegory of the ‘Sublime Point’: Mount Teide, Tenerife.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 300

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781787077690

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787077706

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787077713

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787077720

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11477

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (December)

- Keywords

- Surrealism and desire Sublimation and repression Idealism and materialism

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. XIV, 314 pp., 16 fig. col., 14 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG