Writing for Freedom

Body, Identity and Power in Goliarda Sapienza's Narrative

Summary

The study follows Sapienza’s autofictional journey from the painful reconstruction of the self in Lettera aperta [Open Letter] and Il filo di mezzogiorno [Midday Thread], to Modesta’s rebellious adventure in L’arte della gioia, to the playful portrayal of childhood in Io, Jean Gabin [I, Jean Gabin] and, finally, to the representation of prison life and queer desire in L’università di Rebibbia [Rebibbia University] and Le certezze del dubbio [The Certainties of Doubt]. Themes of freedom, the body, nonconformist gender identities and sexuality, autobiography and political commitment are explored in connection to a variety of philosophical discourses, including Marxism, feminism, psychoanalysis and queer theory. From a position of marginality and eccentricity, Sapienza gives voice to a radical aspiration to achieve freedom and social transformation, in which writing and literary communication are conferred a fundamental role.

This book was the winner of the 2015 Peter Lang Young Scholars Competition in Women’s Studies.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Outside the Norm: The Re-construction of Identity in Lettera aperta and Il filo di mezzogiorno

- Chapter 2: ‘Gioiosa forza nomade’: Epicureanism and Anarchism in L’arte della gioia

- Chapter 3: Io, Jean Gabin: Staged Identities and Anarchist Love

- Chapter 4: Speaking from the Margins: L’università di Rebibbia and Le certezze del dubbio

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

I am grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK, and Oriel College, UK, which funded my doctoral studies at the University of Oxford. I also wish to thank the Isaiah Berlin Fund, the Christina Drake Fund, the Fiedler Memorial Fund and the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, University of Oxford, for awarding me the Scholarships that enabled me to travel to Italy to carry out research interviews.

I give heartfelt thanks to Giuseppe Stellardi, for supporting me over the years with kindness, constancy and precision, stimulating discussions which helped me find the right direction for my research. I also wish to thank several people who contributed to this project: Sharon Wood and Emmanuela Tandello Cooper, who examined my PhD thesis and provided valuable advice as to how to structure this book; Michael Subialka, David Bowe, Riccardo Liberatore and Matthew Reza, whose thorough editing greatly improved the final shape of this book; Vilma de Gasperin, whose feedback and bibliographical suggestions had a substantial impact on my approach to Sapienza; Charlotte Ross, for her generous and detailed feedback on Chapter 3 on Io, Jean Gabin, which urged me to dig deeper into the theoretical aspects of the research; Katrin Wehling-Giorgi and Emma Bond, for the exciting collaboration on the conference Goliarda Sapienza in Context and the related volume; Giovanna Providenti, for providing me with relevant information about Sapienza, including a copy of the typescript of Lettera aperta; Ruth Glynn, Florian Mussgnug, Daniela La Penna and Ann Hallamore Caesar, for their interest in my project in its initial stages, which helped me believe I was going in the right direction; Angelo Pellegrino and Paola Pace, for welcoming me several times in their house in Rome, and for our precious conversations about Sapienza. Adele Cambria, who shared with me her memories of Sapienza, and allowed me to see her copy of the typescript of Io, Jean Gabin. Paola Blasi, who was so kind to talk to me about her life-long friendship with Sapienza. I also offer very sincere thanks to the editorial board of the 2015 Peter Lang ← vii | viii → Young Scholars Competition in Women’s Studies, for awarding me the prize that enabled me to publish this book; the two anonymous readers, who provided very helpful comments on the draft of the manuscript; and to Laurel Plapp at Peter Lang, who assisted me throughout the realization of this book project.

Lastly, my wholehearted gratitude goes to Tecla Castella, my family and my friends, without whose unfailing love and support this project would not have been possible.

Permission to quote from the translation Goliarda Sapienza, The Art of Joy, translated by Anne Milano Appel (2013), has been granted by Penguin and by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Angelo Pellegrino, for the Estate of Goliarda Sapienza through Piergiorgio Nicolazzini Literary Agency, has generously granted permission to quote from Goliarda Sapienza, Lettera aperta (1997), Il filo di mezzogiorno (2003), L’arte della gioia (2008), L’università di Rebibbia (2006), Le certezze del dubbio (2007) and Io, Jean Gabin (2010).

Earlier versions of parts of Chapters 1, 2 and 3, are published in the article ‘The Performative Power of Narrative in Goliarda Sapienza’s Lettera aperta, L’arte della gioia and Io, Jean Gabin’, Italian Studies, 72, 1 (2017), 71–87.

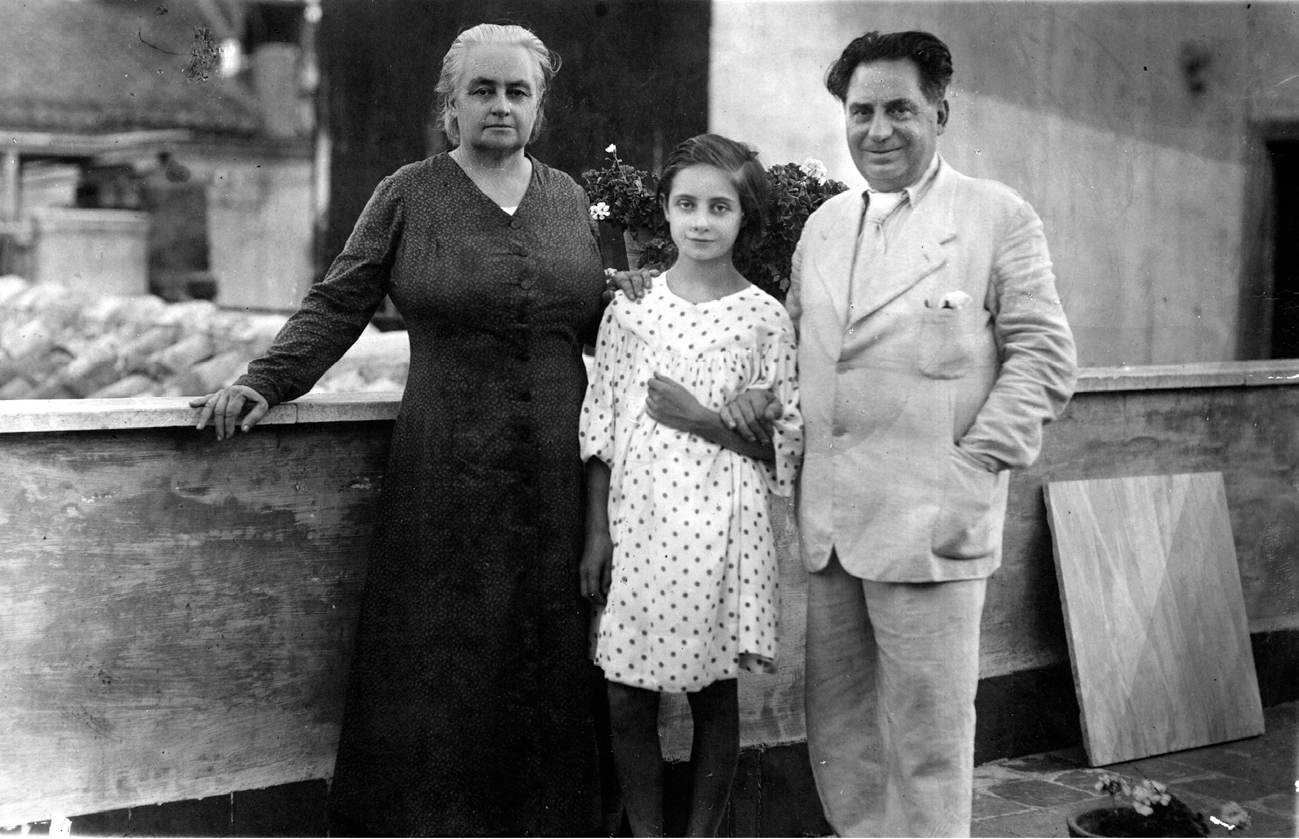

Figure 1: Goliarda Sapienza with her mother, Maria Giudice, and her father, Peppino Sapienza. © Archivio Sapienza Pellegrino. ← x | xi →

Figure 2: Goliarda Sapienza in the 1950s. © Archivio Sapienza Pellegrino. ← xi | xii →

Figure 3: Goliarda Sapienza in 1976. © Archivio Sapienza Pellegrino.

Sapienza: Life and Works

After a long period in oblivion, Sicilian writer Goliarda Sapienza is rapidly coming to be regarded as a major figure in modern Italian literature. Her literary production is characterized by a subversive and eccentric attitude towards norms and institutions, together with an aspiration to achieve individual and social transformation, in which writing and literary communication are granted a fundamental role. This book explores the representation of freedom in Sapienza’s narrative, by looking at the interplay between body, identity and power. The main aspects of this interplay taken into consideration here are gender, sexuality and political ideology.

Sapienza was born on 10 May 1924 in Catania, Sicily.1 Her mother, Maria Giudice (1880–1953), originally from Lombardy, was one of the most prominent members of the Italian Socialist Party, as well as a feminist activist.2 Giudice collaborated with national and international left-wing intellectuals, including such names as Antonio Gramsci, Umberto Terracini, Angelica Balabanoff and Lenin, and was on the front line fighting for women’s and workers’ rights both through demonstrations and journalism, activities for which she was repeatedly imprisoned. In 1919 Giudice moved to Sicily to help organize the local socialist divisions and trade unions. Her ← 1 | 2 → former partner, Carlo Civardi, had died fighting as a soldier in World War I, leaving her with seven children. In Catania, she met Peppino Sapienza (1880–1949), a socialist comrade himself, who came from a working-class family but succeeded in becoming a lawyer.

Maria and Peppino started a new family. Goliarda was their only child, while many step-siblings from her parents’ previous families lived in the same house in Via Pistone, Catania. During her childhood, she was surrounded by a nonconformist environment, characterized by loose boundaries between family and non-family members, a mix of different class backgrounds and an active political involvement, oriented towards feminism, anti-fascism and anti-clericalism. Since her father did not want her to be indoctrinated by fascist propaganda, at the age of fourteen he took her off formal schooling. She taught herself drama and piano, and at the age of sixteen she won a scholarship from the Accademia d’arte drammatica in Rome, where she moved with her mother. In 1943, after the armistice, she fought as a partisan with her father, who was involved in Pertini and Saragat’s jailbreak. After the war, Sapienza went back to acting in theatres and started to work in the film industry. In 1947 she met Neorealist film director Francesco Maselli, who was her partner for twenty years and with whom she frequented Roman intellectual circles, comprising prominent figures such as Alberto Moravia, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Luchino Visconti, Attilio Bertolucci, Cesare Zavattini and Elsa Morante. In 1953, Maria Giudice died, after a long period of psychological decline. Her death coincided with Sapienza’s first steps in writing, initially with a preference for poetry.3

In the late 1950s Sapienza started suffering from serious depression and, after a failed suicide attempt, was subjected to electroconvulsive therapy, which caused her to partially lose her memory. She recovered thanks to psychoanalytic therapy and through writing, publishing two semi-autobiographical novels: Lettera aperta [Open Letter], a journey into her childhood, and Il filo di mezzogiorno [Midday Thread], where she recounts her ← 2 | 3 → own therapeutic experience.4 Sapienza then dedicated herself completely to writing, spending approximately ten years on her major novel, L’arte della gioia [The Art of Joy].5 She descended into poverty and spent a few days in prison after being convicted of theft. Her prison experience is recounted in L’università di Rebibbia [Rebibbia University], while in Le certezze del dubbio [The Certainties of Doubt] she tells the story of her transition from prison to freedom and her relationship with a woman she met in Rebibbia.6 In the last years of her life she taught acting at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome and wrote more works, some of which were published posthumously. She died in Gaeta in August 1996.

Overall, Sapienza’s narrative is closely informed by the experiences that characterized her life – her atypical upbringing, her early encounter with socialist and feminist political commitment, her work in theatre and cinema, depression, her experience with psychoanalysis, poverty and prison. From a position of marginality and eccentricity, Sapienza expresses a radical desire for freedom and for new, creative ways to conceive personal identity and human relationships, addressing a subversive criticism to the very core of Western thought and society, and representing an alternative and original voice in twentieth-century Italian literature.

During her life, Sapienza published four works: Lettera aperta; Il filo di mezzogiorno; L’università di Rebibbia and Le certezze del dubbio. To these should be added the publication in 1970 in Nuovi Argomenti of Destino coatto [Compulsory Destiny], a collection of short monologues ← 3 | 4 → recounting hallucinations and obsessions;7 Vengo da lontano [I Come From Far Away], a short text on the theme of peace, published in 1991 in a collection of articles by a group of women writers on the occasion of the Gulf war;8 and the first part of L’arte della gioia, in 1994.9

Sapienza’s major novel, L’arte della gioia, written between 1967 and 1976, was rejected by several publishers in the course of over twenty years; it was published in full only after Sapienza’s death in 1998, and its popular success came thanks to the French, German and Spanish editions.10 This eventual success led to the Einaudi edition in 2008, which launched her work in Italy, and to the posthumous publication of a number of other works: a short semi-autobiographical novel, Io, Jean Gabin [I, Jean Gabin];11 two collections of poems, Ancestrale [Ancestral] and Siciliane [Sicilian Poems] (the latter in Sicilian dialect);12 two volumes of diaries;13 a collection of plays and cinema subjects, Tre pièces e soggetti cinematografici [Three Plays and ← 4 | 5 → Film Synopses];14 the short story Elogio del bar [In Praise of the Café];15 and the novel Appuntamento a Positano [Meeting in Positano].16 There is some uncertainty concerning the editing undergone by the posthumous works, since none of them contains a critical apparatus. In particular, the poems collected in Ancestrale and Siciliane, and the two volumes of diaries, lack information that would clarify the selection and editing criteria.17 Only a careful investigation into the manuscripts will shed light on the editorial processes and choices involved in the publication of these works.18

Readership and Criticism

Since Sapienza’s success is very recent and her work not yet established in the Italian literary canon, the choice to make this author the object of a monographic study already contains an implicit argument in favour of her relevance and significance. Two types of considerations support this choice. First, Sapienza is an author of substance, who deserves a place in the panorama of Italian and European literature, and through the exploration of her texts I endeavour to point out the elements of interest and originality that render them worthy of critical attention and appreciation. Second, after a long period of oblivion Sapienza’s works, and especially L’arte della gioia, are now finding popular success and achieving critical ← 5 | 6 → recognition, on a national as well as international level. Against the resistance of major publishers, the success of Sapienza’s works has been enabled by readers and independent publishers, who allowed L’arte della gioia to circulate and find in France, Germany and Spain its way to a wider readership.19 Since the Einaudi edition of L’arte della gioia in 2008, literary reviews, blogs, cultural events, readings and talks are multiplying in and outside of Italy. Moreover, Sapienza’s life and works have become a source of inspiration to other artists, generating plays, performances, life writing and music.20 Sapienza’s success in finding this wider readership qualifies her work as half-way between experimentalism and legibility, as she blurs genre boundaries, intensely manipulates linguistic and narrative structures, and expresses radical social criticism, but nevertheless maintains an affable attitude towards her readers, who are invited to participate in her search for identity and freedom.21 Whereas for a long time the ideal reader implicitly postulated by Sapienza’s texts did not mesh well with her actual readers, contemporary readers seem to correspond to that ideal more fully, and they are thus more receptive to her works. If Sartre described the work of art as ‘a spinning top which exists only in movement’, implying that the text becomes communication only through a reader, Sapienza’s texts, ignored for decades, are now undoubtedly spinning fast.22

Participating in the rising interest in Sapienza’s works, in the past few years critics have begun to explore her texts. The core academic literature thus far comprises Sapienza’s biography, La porta è aperta, by Giovanna Providenti; the critical introductions and afterwords that accompany ← 6 | 7 → most editions of Sapienza’s works; two essay collections in Italian, Quel sogno d’essere, edited by Providenti, and Appassionata Sapienza, edited by Monica Farnetti,23 and one in English, Goliarda Sapienza in Context, edited by Emma Bond, Katrin Wehling-Giorgi and myself;24 and a number of journal articles in Italian, English, Spanish and French. Among these, this study dialogues extensively with Charlotte Ross’s articles, which are focused on the representation of gender and sexuality in Sapienza’s narrative.25 Furthermore, Sapienza’s works are discussed alongside those of Elena Ferrante and Julie Otsuka in an edited volume on the notion of ‘ambivalence’ freshly published in Italian.26 This critical bibliography is augmented by the growing number of literary reviews in several languages, which were boosted by the publication in the UK and the US of the English translation of L’arte della gioia in 2013.27

Critical work so far has endeavoured to reconstruct Sapienza’s life and artistic activity and to identify the main themes and characteristics of her works. It has revealed the centrality of autobiography in her production, the relationship between selfhood and writing, her nonconformist representation of gender identity, motherhood and sexuality, her work’s conflicted relationship with psychoanalysis and her original depiction of women’s prison. In addition, the edited volumes Goliarda Sapienza in Context and ← 7 | 8 → Dell’ambivalenza begin to trace a map of intertextual relationships and affinities with Italian and international literature and thought. Sapienza studies are thus a new, fast-growing field, characterized by an initial effort to explore the author’s work in several directions. Consequently, the body of research is still very fragmented, consisting of several survey-like critical interventions, and a few more detailed, specifically focused analyses, which nonetheless do not yet provide an organic picture of the whole.

This book is the first full-length monographic analysis of Sapienza’s literary production and seeks to delineate its central poetics, which, I argue, has its pivotal tension in the ideal of freedom. Freedom is characterized as the firm opposition to any form of oppression, and as the possibility of accessing and enjoying bodily pleasures and empathetic relationships of care. Sapienza’s works trace out a strenuous deconstruction of oppressive norms and structures, and they aim at retrieving a space of powerful bodily desire, which constitutes the foundation of the process of becoming a subject and an agent of social transformation. A distinctively original aspect of this research in this sense is the importance it attributes to the political dimension of Sapienza’s works, in terms of their attention to ideology and literary engagement, and the close relationship they establish between the individual and political spheres. The processes of identity formation and the political domain are closely interconnected in Sapienza’s works, and it is in the material presence of a body with desires that they find their main common ground.

Aims, Methodology and Theoretical Framework

This book comprises four chapters, each one developing a close textual analysis of one or more works: Lettera aperta and Il filo di mezzogiorno in Chapter 1; L’arte della gioia in Chapter 2; Io, Jean Gabin in Chapter 3; L’università di Rebibbia and Le certezze del dubbio in Chapter 4. Each chapter looks at the representation of identity formation and the characterization of freedom in the relevant work(s), progressing from the exploration of the ← 8 | 9 → internal composition of the self to the analysis of identity in its interpersonal and socio-political dimension. Moreover, each chapter includes the analysis of narrative structures and the narrating voice, investigating the central role of writing in the evolution of Sapienza’s narrative. The separate analyses of individual works have been privileged over a thematic comparative approach in order to highlight the distinctiveness of each work and the evolving nature of her writing, avoiding the impression of Sapienza as an auctor unius libri. Since, with the exception of L’arte della gioia, Sapienza’s works have not been translated into English, the extensive use of primary quotations, also provided in English translation, which serve primarily the purposes of close reading, will also enable non-Italian speakers to gain insight into Sapienza’s production.

Sapienza’s works first emerge as an effort to reconstruct her disrupted memory and identity, which dovetails with a criticism of social norms and oppressive power relationships. They can fruitfully be ascribed to the category of ‘autofiction’ – a combination and contamination of autobiography and fiction.28 ‘Autofiction’ was used initially to designate the impossibility of truth and transparency of meaning in modern autobiographies; it is then used, especially in the Francophone context, to refer more broadly to autobiographical novels featuring an undecidable boundary between reality and fiction. Considerably ahead of their times, Sapienza’s novels combine both meanings, as they explore the mechanisms of mediation, distortion and creation at work in autobiographical writing, and embrace a hybrid form of autobiography through which the author manipulates her own story. Chapter 1 analyses how the adult narrator of Lettera aperta and Il filo di mezzogiorno engages with the recollection of her childhood, her relationship with her extraordinary family and her troubled social integration, in order to retrieve a sense of self and the vitality with which she had progressively lost contact. Faced with the challenge of making sense ← 9 | 10 → of a series of contradictory models of gender, sexuality, class and political ideology, Goliarda, the child protagonist, struggles to orient herself and master the position of radical diversity that is imposed on her. In the midst of a whirl of incongruous messages, she becomes acutely aware of the power underlying human relationships, where the need for love, also expressed as the need to please others, gives rise to an excruciating conflict with her search for autonomy. In Il filo di mezzogiorno, the narrator recounts her psychoanalytic therapy, internalizing but also negotiating the therapist’s interpretations of her past, especially as concerns gender identity and sexuality. Through this double exploration of her childhood, characterized by fragmentation, ellipses and analogical connections, the narrator seeks to re-establish contact with her own living body as a source of identity and agency.

Chapter 2 follows Modesta’s long journey towards the realization of a radical form of freedom, from the initial experience of sexual pleasure to the exercise of violence and, finally, the acceptance of relationships of dependence and care and of the impossibility of exerting full control. The first part of the chapter explores the type of subject that, in L’arte della gioia, takes on a struggle for freedom. It reflects on the centrality of the body within the construction of the protagonist’s self and her instrumental use of rationality, which can be ascribed to Epicurean ethics. The novel features the coexistence of different configurations of the self, which my analysis relates to different positionalities with respect to power. Specifically, the adoption of a strong and oppositional attitude is rendered necessary in order for a subaltern subject to reject oppression, but the protagonist’s ultimate aim is to escape the replication of a binary logic of domination and to enjoy a weak and fluid identity, centred on the pleasure of the senses, queer desires and empathetic relationships of care. From a political perspective, L’arte della gioia continues and expands the deconstructive stance put forward in the autobiographical works. It addresses several centres of power and domination, among which Sapienza includes the PCI’s agenda and its militants’ attitudes, and realizes a form of veritably anarchist literary engagement. This political stance entrusts the novel with the task of promoting a yearning for freedom among the readers. ← 10 | 11 →

Details

- Pages

- XII, 326

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787077843

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787077850

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787077867

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034322423

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11486

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (February)

- Keywords

- Goliarda Sapienza freedom autobiography and fiction autofiction Italian literature women’s writing gender and sexuality studies queer studies

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2018. XII, 326 pp., 3 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG