Wickham Steed

Greatest Journalist of his Times

Summary

«Steed is a fascinating character, who moved easily and influentially between the worlds of journalism, diplomacy and academia […]. It has been a long wait for a biography, but this one is so thorough and definitive that I am sure it will be a long wait before a rival emerges.»

Prof. Tom Buchanan, University of Oxford

«This work constitutes the first biography of Wickham Steed who, […] was a seminal figure within the media and political worlds of both Britain and Europe during the earlier half of the twentieth century. […] Beyond offering us a personal history of a fascinating and highly influential figure, the author provides us with fresh insights into both British domestic politics and high society and the international diplomacy of a particularly turbulent era.»

Prof. Conan Fischer, University of St. Andrews

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- The Continental Englishman

- Chapter 1: Early Life

- England

- The Continent

- Chapter 2: Foreign Correspondent

- Berlin

- Rome

- Vienna

- Budapest

- The Balkans

- The Hapsburg Monarchy

- London

- Chapter 3: The Great War

- The July Crisis

- The Times at War

- Undoing Austria-Hungary

- The Principle of Nationality

- Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia

- The Peace Conference

- Chapter 4: Editor

- The New Editor

- The Editor at Work

- The Editor Abroad

- The Editor Dismissed

- Photos 1–13

- Chapter 5: Pundit

- A New Life

- The Review of Reviews

- Through Thirty Years

- Britain

- France

- America

- Germany

- Rose and Violet

- The League of Nations

- Chapter 6: Crusader

- Italy

- Hitler

- Appeasement

- Steed’s Secret Service

- “The Wickham Steed Affair”

- Focus

- Spain and Munich

- Chapter 7: The Last War

- War

- Exiles

- Last Years

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index

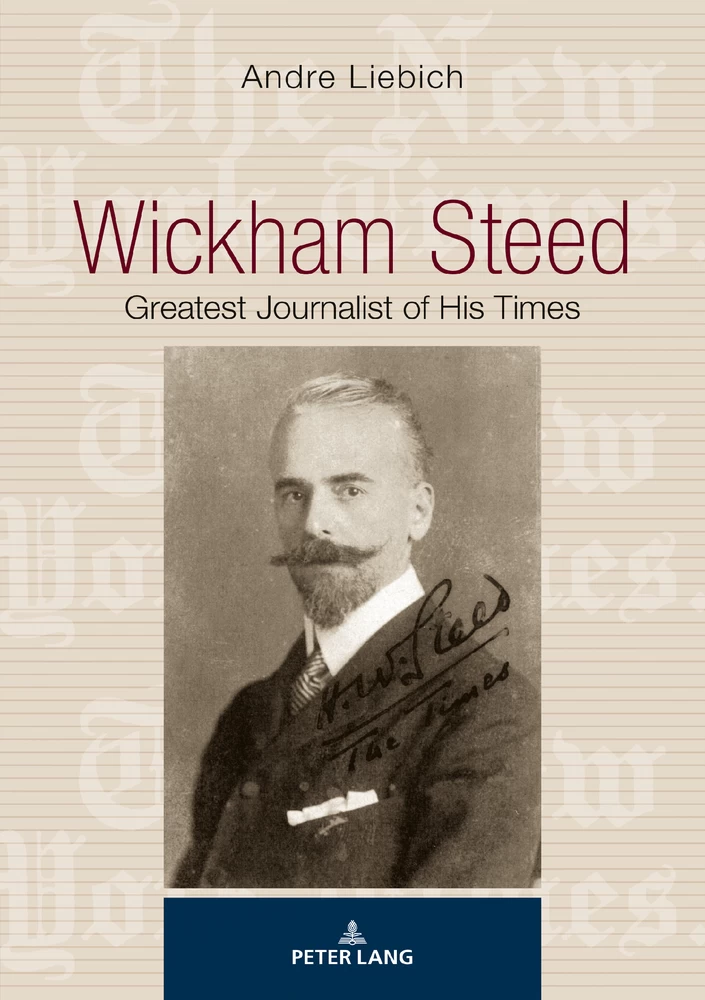

Wickham Steed’s contemporaries often remarked upon his impressive appearance. A handsome and elegant figure, tall and slim, distinguished by a closely cropped pointed beard, he looked as if he had stepped out of a canvas by Velasquez or out of de Champaigne’s classic portrait of Richelieu. They described him as having the bearing and grand manner of an ambassador to the Court of St. James or, alternatively, as looking like a knight errant from the age of chivalry.1 His colleagues at The Times recall their astonishment, sometime before 1914, at first seeing Wickham Steed, already famous as The Times correspondent in Vienna and soon to be their Foreign Editor and later Editor-in-chief: “It was as if a Spanish hildago [sic] had appeared after paying a visit to Savile Row … Apart from dress, he might have been fighting Hawkins or Drake.”2 His impressive appearance was matched by his impressive accomplishments. Cosmopolitan to the core, many marvelled at his perfect command of French, German and Italian, his ability to talk to kings as well as to working-class politicians, and even his qualities as an epicure.3 Described as a “confidante of princes, advisor to statesmen and leader of public opinion,” Wickham Steed was hailed as the “greatest ← 7 | 8 → journalist of his time” upon leaving the editorship of The Times in 1922 and, almost two decades later, many still considered him “probably the greatest authority in the world on Central European politics” while others acknowledged that “no journalist in the thirties other than perhaps J.L. Garvin carried such weight” as did Wickham Steed.4 No wonder that Steed’s colleagues thought that he “too nearly approached genius to be judged by ordinary standards.”5

Beneath the encomia, a recurring theme is that of Wickham Steed’s “foreignness.” The “foreign looking man with the pointed beard” is how The Times librarian recalled him.6 The political insider Lord Riddell, who admired the fine figure that Steed cut in international society and described him as “brilliant,” also alluded to Steed’s “foreign look.”7 Astutely, Riddell added that “Steed’s cosmopolitanism offended and embarrassed many members of a parochial, hidebound, and pusillanimous British establishment who supposed that someone so different from themselves must be a foreigner.”8 When Steed was appointed in 1919 and then summarily dismissed from the editorship of The Times in November 1922, the suspicions and antipathy he had provoked poured out in the letters sent to Steed’s predecessor who also became his successor: “I regret extremely that one [whom] … I have always considered a cosmopolitan should now occupy your chair. We want now of all times an Englishman here, I think, at any rate a Britisher,” was a typical comment.9 And upon Steed’s dismissal, Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scout movement wrote, “a large number of old friends of ‘The Times’ are glad to see it back in the hands of English gentlemen again.”10 Qualification as a “cosmopolitan” was, indeed, a doubtful compliment. ← 8 | 9 →

And, yet, Steed was as English as one could be. He was born in a village in East Anglia, at the high tide of the Victorian era, in 1871, to a respectable but modest and quintessentially English family. His brothers, with whom he maintained good relations for life, remained in or returned to the Suffolk countryside. Steed attended a local grammar school before moving to the continent to continue his education and launch his career as a journalist. Steed thus never attended an English public school or an English university, much less an Oxbridge college. His courtly and imperious manner was entirely self-acquired. This may explain in part the misgivings that English society, what George Orwell has called “the most class-ridden society under the sun,” felt about Steed even as he rose to the pinnacle of the English establishment as editor of The Times.11 True, Steed’s “chief” as proprietor of The Times, Alfred Harmsworth, created Viscount Northcliffe, also did not have the proper birth or education but he had a huge fortune which compensated (partially, at least) for these inadequacies; Steed enjoyed no such grace. Steed’s defenders declared that underneath the layers of French, Italian and Viennese culture Steed was truly an “Englishman, a protestant and a patriot,” but others remained unconvinced.12 Aware of the slights he experienced in English society, Steed cultivated the foreign ties that inspired such suspicion and the manners of a grand seigneur even as he repressed the social radicalism that lay within him.

There were reasons of substance as well to dislike Steed. At a time when the English political class was fixated on its empire, Steed remained indifferent to the empire. Germanophilia was the rule throughout English society before the First World War and even, to a certain extent, afterwards, while Steed was, from very early on, a vociferous Germanophobe. Instead, he was a friend of France, some thought too firm a friend. To be sure, Steed had his defenders as well. As a leading critic of British appeasement policies in the 1930s puts it, in giving warning of both world wars Steed was too often right to please everybody; he was also wise in defending the Versailles Treaty, against the grain of most elite and public opinion, insisting that territorial revisions would only bring about the revival of the German threat to Europe. “History would ← 9 | 10 → have been somewhat different in this country if he [Steed] had remained editor of The Times,” concludes his admirer.13

Both personality and substance combine to explain the hostility that Steed inspired. He was arrogant – “modesty had never been one of my outstanding vices,”14 he wrote with false self-deprecation. He was a garrulous name-dropper, self-important and, above all, self-righteous. It was this self-righteousness that grated most upon his interlocutors, especially when he took unpopular stances such as his unqualified condemnation of Italian fascism or of any compromises with Hitler. His other foibles, such as his outbursts against Jews or Catholics, were more easily forgiven at the time as they corresponded to prevalent attitudes. Without an established position in English society and without strong friends at home, Steed has been a scapegoat for attacks directed against more powerful individuals, notably against his “chief,” Northcliffe. Steed’s “obsequiousness towards Northcliffe … left nothing to be desired” and Steed “preyed upon Northcliffe’s suspicions and fears like Iago,” writes the Dictionary of National Biography, citing an authoritative study of the British press.15 It is such disparagement by some historians that may explain why, although at least two serious writers, Martin Gilbert and George Donald King McCormick, have considered undertaking it, Wickham Steed is one of the editors of The Times who has not been the subject of a biography.

Wickham Steed’s life is a story that deserves to be told. In spite of his irritating traits and peculiar fixations, one cannot accuse him of failing to be true to principle. Astonishingly for a man prone to self-aggrandisement, he refused honours, including a British knighthood and foreign decorations, accepting only honorary doctorates from two continental universities as these would not infringe upon his independence nor make him beholden to any government. His penchant for conspiracy theories, an inclination that sometimes led him astray, was a professional ← 10 | 11 → deformation for a journalist who amassed significant “scoops” in his career. Steed was also a man of staunch loyalty. It is this rather than any obsequiousness that explains his devotion to Northcliffe. It is this quality that he carried through in his personal life, remaining loyal to the much older woman with whom he shared his life for many years even as he fell in love with the much younger woman whom he married only at an advanced age. Above all, Wickham Steed’s life is a rich fresco of an era. In the words of an authoritative historian, Steed “not only influenced world policy but actually made history.”16 During the First World War and in its aftermath, he was instrumental in the creation of new states throughout Europe and in the establishment of a new order founded upon the internationalist idealism incarnated in the League of Nations. As an independent journalist in the 1920s and 1930s, he led an initially solitary crusade against threats that were later to be called totalitarian. As the Second World War approached, in the course of it, and even afterwards, he threw himself with zest into the new media that was radio, a powerful voice broadcasting analyses of international politics throughout the world.

This book is based upon Wickham Steed’s published and unpublished writings, including his extensive correspondence now located in the Manuscripts Division of the British Library. It draws upon archival sources elsewhere as well as a vast array of printed sources that illuminate the events and issues with which Steed was involved in the course of some sixty years in the public light. As a specialist on Central and Eastern Europe, I came upon Steed by accident as I was researching the case for Czechoslovak independence during the First World War. The rich texture of Steed’s life attracted me and persuaded me to write a biography of this brilliant, complex and sometimes flawed figure whose story allows us to follow through the lens of an exceptional individual so many of the historical moments that defined the twentieth century.

1 “Velasquez portrait,” The Newspaper World, 9 December 1922; “Richelieu,” R. Lacoste, The Times, 18 January 1956. “Court of St James,” R. Pound and G. Northcliffe, Northcliffe, London: Cassel, 1959, p. 700; “knight errant,” The Times, 14 January 1956.

2 Hugh MacGregor, article prepared for The Times House Journal (28 January 1956) but not published. TNL Archive, Steed Papers, TT/HWS/3/8/3.

3 “kings,” Manchester Guardian, 14 January 1956; “working-class politicians,” E. Spier, Focus: A Footnote to the History of the Thirties, London: Oswald Wolff, 1963, p. 102; “epicure,” J. Matthews, “Wickham Steed as a Foreign Correspondent,” Journalism Quarterly 33:2 (1956) 194–200 and J. G. E., letter to The Times, 17 January 1956.

4 “confidante,” Washington Post, 14 January 1956; “greatest journalist,” The Graphic, 16 December 1922; “Central European politics,” Tatler, 18 January 1938; G. D. K. McCormick to Joan Stevenson, 16 October 1966, Steed Papers, BL 74137.

5 H. MacGregor, unpublished article.

6 The Times librarian to H. MacGregor, 28 January 1956, Steed Papers, TNL Archive, TT/ED/HWS/3/8/2.

7 Lord Riddell’s Intimate Diary of the Peace Conference and After, London: V. Gollancz, 1933, p. 344.

8 Riddell, p. 344.

9 M.C. Sidmonk to G. Dawson, 24 February 1919, Dawson Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

10 R. Baden-Powell to G. Dawson, 23 January 1923, Dawson Papers.

11 G. Orwell, “England, your England,” in The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, London: Secker & Warburg, 1941, p. 33.

12 The Times, 14 January 1956.

13 A.L. Rowse, All Souls’ and Appeasement, London: Macmillan, 1961, p. 6.

14 Steed to C. Kent, 1 December 1948, TNL Archive, H.W. Steed Managerial File, TT/Man/1.

15 A. J. A. Morris, “Steed, Henry Wickham (1871–1956),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (London, Oxford University Press, 2004) article 36260, quoting S. Koss, The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Great Britain, vol. 2, The Twentieth Century, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1984, pp. 350 and 358.

16 Arthur J. May, The Passing of the Hapsburg Monarchy 1914–1918, Philadelphia; University of Pennsylvania Press 1966, vol. I p. 23.

In his later years, Henry Wickham Steed reminisced about the village of Long Melford where he was born on 16 October 1871:

I grew up in a village in East Anglia that was at once agricultural and industrial. Remnants of the feudal system, with its patriarchal quality and lingering sense of social trusteeship, were to be seen and felt on every hand, particularly in the relations of the lords of the manors to their tenants and dependents; while the “industrial revolution” … made its influence felt in textile factories and in a foundry for the manufacture of agricultural machinery.17

In its outward appearance, Long Melford has changed little from Wickham Steed’s time. It is a picturesque village of some 3000 inhabitants, a number almost unchanged for well over a century. Located in the middle of the Stour valley, some 25 miles from Cambridge and 70 miles from London, it was long a convenient posting stop on the London-Bury St Edmunds- Norwich coach route. Already a bustling “cloth” village in Tudor times, during the English Civil War in the 1640s Long Melford aligned itself firmly with parliamentarian forces against the royalists chasing out its most prominent Catholic aristocrat. In the course of the nineteenth century the village added horsehair weaving, flax works and mat-making to its existing activities, with a branch of the Great Eastern Railway making it easier to bring these products to market after 1865.

Long Melford boasts the longest high street in East Anglia and it was here, along Hall Street, that Wickham Steed grew up. The family home, the Gables, originally a traditional timber house from Tudor times, had been much rebuilt so that its most prominent feature was, and still is, a Victorian façade. It was an unpretentious house where Joshua ← 13 | 14 → Steed, a village solicitor, and his wife, Fanny Wickham, the daughter of a large Wiltshire farmer, raised their four sons and daughter, with the help of a nursemaid.

The Steeds had lived in Long Melford for at least three centuries but Joshua Steed, Wickham’s father, was the first to become something of a village notable. He entered a local solicitor’s office as a clerk, became a manager and, after having himself qualified as a solicitor in 1881, rose to partnership in the firm renamed “Fisher and Steed.” As acting magistrates’ clerk for both the Melford and Boxford Sessions judges, acting clerk for the Commissioner of Taxes, and agent of Earl Howe’s extensive Suffolk and Essex estates, Joshua Steed enjoyed local professional prominence. It was his social involvement, however, that did most to win him the respect of the community. He was closely involved in the Stoke and Melford Union, a benefit and sickness society, and he was vice-chair of the British Workmen’s Tea and Coffee Reading Rooms, devoted to the intellectual and moral improvement of workers. Most significantly, Joshua Steed was a leader of the local Congregational Church. He was a trustee, general manager and organist of the eighteenth century Congregational chapel, situated next door to the Steed home. From an early age he taught Sunday School and he was a manager of the “British School” for children of non-conformist families.

Congregationalists, rooted in Puritan non-conformism, were a minority faith but they enjoyed a measure of official, though not social, recognition with a Congregationalist minister in every Liberal government but no Congregationalists in elite institutions such as the Diplomatic Corps. Joshua Steed was politically involved as well. He acted as electoral agent for Cuthbert Quilter, the Liberal and then Liberal Unionist Member of Parliament for Sudbury. As Liberal Unionists concluded an alliance with Conservatives in their common opposition to Irish Home Rule in 1886, Joshua Steed became the vice-president of the local Conservative Association, whose strong views on Ireland he supported, even as he continued to act as Quilter’s electoral agent. Quilter’s election platform was purely domestic: he advocated the disestablishment of the Church of England, criticized the disenfranchisement of those on medical relief, called for pure water supply to every cottage, and promoted his signature cause: legislation to ensure that beer was made from pure water malt and hops not molasses, sugar or salt. Joshua ← 14 | 15 → Steed concurred with him in all of these. In his private capacity, Joshua Steed pleaded successfully for lighter fines on rioters arrested after an electoral riot and, as secretary of the organizational committee to celebrate the Queen’s jubilee in 1887, he worked to establish local recreational facilities. Wickham Steed’s most vivid recollection of his father was that of Joshua Steed earnestly discussing a long-standing interest in workers’ insurance and old age pensions with the village curate, John Frome Wilkinson, author of a book entitled Mutual Thrift.

Joshua Steed was a household name in Long Melford, praised for “his honourable conduct, strict integrity, sound judgment and constant and reliable friendship.”18 However, the Steeds did not belong to the first circle of Long Melford society. This consisted of the Hyde Parkers, a distinguished naval family headed at the time by the Reverend Sir William Hyde Parker, tenth baronet, of the splendid Elizabethan manor, Melford Hall, where his cousin Beatrix Potter sometimes stayed. The elite also included Captain Edward Bence, who lived at Kentwell Hall, another stately Tudor house that the Starkie Bences had purchased in 1839. As each of these families had six to nine children and numerous staff they were a prominent presence in the village. A newcomer to this select circle was the Reverend C. J. Martyn, rector of the parish of Long Melford who had purchased the living of its grand fifteenth century Holy Trinity church in 1869 and presided over the parish for almost a quarter of a century. Martyn had been educated at Harrow and Christ Church, Oxford. He was the only clergyman at the select Marlborough Club, whose members had to be personally approved by the Prince of Wales, and in the 1890s he became chaplain-in-ordinary to the Queen. In Melford he displayed his own livery: light blue coat piped with red, gilt button, scarlet waist coat, white breeches, top boots, gold band and braid to the hat. When Wickham Steed filled out his application form to The Times he listed Cuthbert Quilter MP and the Rev. C. J. Martyn as his references.

Details

- Pages

- 378

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034332736

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034332743

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034332750

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034332767

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13426

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (October)

- Keywords

- Wickham Steed Central Europe Journalism Britain Twentieth Century Europe 1900-1950

- Published

- Bern, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018. 378 pp., 9 fig. col., 5 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG