Writing the Self, Writing the Nation

Romantic Selfhood in the Works of Germaine de Staël and Claire de Duras

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Romantic Novel in France

- Chapter 1: Between Self and Other: The roman personnel

- Chapter 2: The English Malady: Towards a Transnational mal du siècle

- Chapter 3: Patrie and père: Shaping Masculinity

- Chapter 4: A Woman’s Place in the Nation

- Chapter 5: On England: Between Nationhood and Cosmopolitanism

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Stacie Allan

Writing the Self,

Writing the Nation

Romantic Selfhood in the Works of

Germaine de Staël and Claire de Duras

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • New York • Wien

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National-bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Allan, Stacie, 1987- author.

Title: Writing the self, writing the nation : romantic selfhood in the works of Germaine de Staël and Claire de Duras / Stacie Allan.

Description: Oxford ; New York : Peter Lang, [2019] | Series: French studies ; 37 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018008104 | ISBN 9781788742085 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Staeël, Madame de (Anne-Louise-Germaine), 1766-1817-Criticism and interpretation. | Duras, Claire de Durfort, duchesse de, 1777-1828-Criticism and interpretation. | Self in literature. | Gender identity in literature. | Women and literature-France-History-18th century. | Women and literature-France-History-19th century.

Classification: LCC PQ2431.Z5 A494 2018 | DDC 843/.6-dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008104

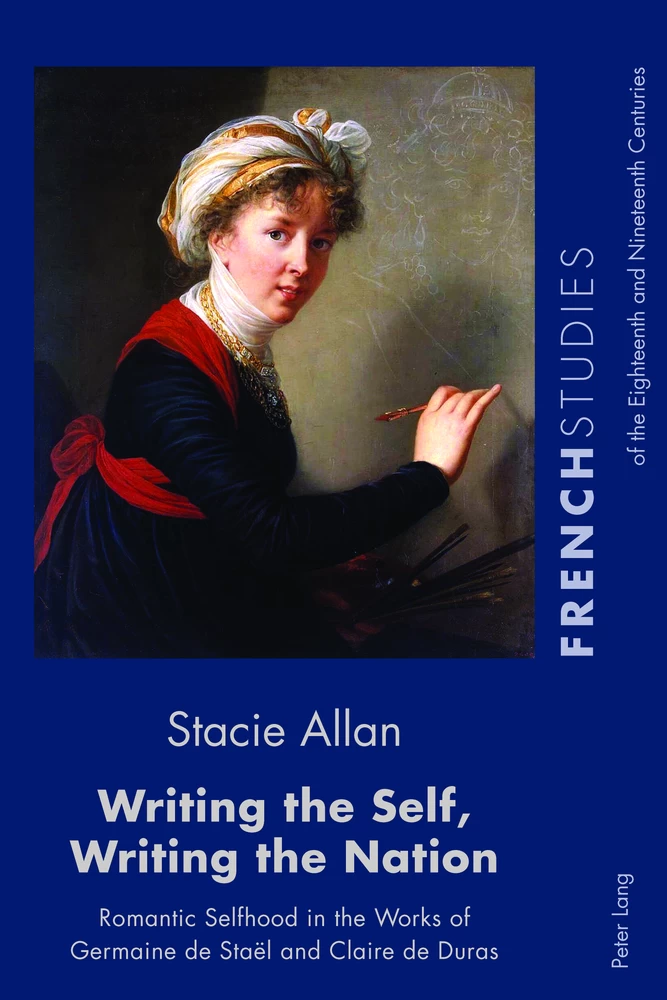

Cover image: Self-Portrait by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, 1800, distributed under a CC BY-SA 3.0 License.

|

ISSN |

1422-7320 |

||

|

ISBN |

978-1-78874-208-5 (print) |

ISBN |

978-1-78874-210-8 (e-pub) |

|

ISBN |

978-1-78874-209-2 (ebook) |

ISBN |

978-1-78874-211-5 (mobi) |

© Peter Lang AG 2019

Published by Peter Lang Ltd, International Academic Publishers,

52 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LU, United Kingdom

oxford@peterlang.com, www.peterlang.com

Stacie Allan has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this Work.

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution. This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

About the book

The French Revolution represents a pivotal moment within the history of personhood in France, where gender and national differences provided the foundations of society. As such, these constructs feature as ideological battlegrounds in the search for identity and self-expression within the Romantic literature published between the revolutions of 1789 and 1830. This book considers Germaine de Staël’s and Claire de Duras’s depictions of men’s and women’s shared and diverging lived experiences to offer an innovative transnational perspective on the usually male-focused mal du siècle. Its methodology combines feminist revisions of the novel, situated reading practices, and life writing research with an intersectional approach to gender and nationhood. This framework presents a dialectical relationship between sameness and difference on formal and thematic levels that challenges the construction and enforcement of binaries within early nineteenth-century legislation, discourse, and culture. Beyond Staël’s and Duras’s intertextual relationship, this book promotes the importance of an understudied period in literary scholarship, clarifies women’s role within French Romanticism, and explores the tense relationship between the self and the nation.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

Between Self and Other: The roman personnel

The English Malady: Towards a Transnational mal du siècle

Patrie and père: Shaping Masculinity

On England: Between Nationhood and Cosmopolitanism

Index ←v | vi→ ←vi | vii→

This book and the doctoral thesis on which it is based were written on trains travelling between Oxford and Bristol (and on the station platform at Didcot Parkway en route), on planes bookending weekends away, and buses commuting to London during a stint of teaching. Parts of the book have been presented in Gettysburg and Coventry, Paris and Sheffield, Berlin and Bristol. Much like the two women upon which it centres, it is a piece of work that has travelled. Much like the ideas of these two women, it has been developed and enriched in conversation with others.

Completing a monograph without institutional support poses certain challenges, and I am especially grateful to the friends and mentors who read through my proposal, commented on sections, and gave me advice. In particular, I would like to thank my PhD supervisor Bradley Stephens who supported the project from the beginning. Stimulating conversations with and friendly support from Clare Siviter, Christie Margrave, Jennifer Rushworth, and Kate Astbury have been of immense value. I’m also very appreciative that Tom Harding and Katja Wiech allowed me to work flexibly whilst I completed the manuscript. Finally, I must mention the unwavering companionship and encouragement of Johnny McFadyen, who patiently read through, corrected, and offered feedback on this material in its various guises over the years.

S.A. Rheinsberg, November 2018

In Mémoires d’outre-tombe (1849), François-René de Chateaubriand, the grandfather of French Romanticism, described his chère sœur and devoted friend Claire de Duras as ‘[une] personne si généreuse, d’une âme si noble, d’un esprit qui réunissait quelque chose de la force de la pensée de madame de Staël à la grâce du talent de madame de La Fayette’ [such a generous person with a noble soul and a spirit that united something of the intellectual magnitude of Madame de Staël with the elegant talent of Madame de Lafayette].1 By comparing Duras to French Romanticism’s other founding thinker, Germaine de Staël, and the author of one of the first European novels, Marie-Madeline de Lafayette, Chateaubriand inscribes the author into two traditions that underpin nineteenth-century literary history in France, two traditions that tend to be dominated by male writers within existing scholarship. Despite the recent ‘Ourika mania’ of teaching Duras’s 1823 text as part of university syllabi in the United States and beyond, the author’s critical reputation does not extend to the heights of Chateaubriand’s appraisal.2 Similarly, whilst Duras’s contemporary and friend Staël is, of course, recognized as a key proponent of European Romanticism, her work does not receive the same level of scholarly attention←1 | 2→ within the French tradition as later (male) canonical writers, particularly among dix-neuvièmistes.

Taking Staël’s and Duras’s hitherto unexplored intertextual relationship as its primary subject, this book places women back at the centre of French Romanticism and the novel’s development across the nineteenth century. Its dual focus on novel writing practices and the complex and evolving concept of subjectivity in France after 1789 reveals the two to be interrelated: gendered perceptions of men and women influenced the reception of different types of novels, and novels contributed to individuals’ understanding of themselves and their relationship to the nation. The novel’s rise is generally understood to coincide with that of nationalism; its compositional processes, as Benedict Anderson argues, ‘provided the technical means for “re-presenting” the kind of imagined community that is the nation’.3 Such a reading presents the novel as bounded, national and gendered – qualities that are reflected in the nation itself. According to Anne McClintock, ‘nations are contested systems of cultural representation and legitimize people’s access to the resources of the nation-state […]. Nations have historically amounted to the institutionalization of gender difference’.4 Analogously, when it comes to the nineteenth-century novel in France, literary history, as Margaret Cohen observes, ‘offers few cases where gender and genre line up so neatly’.5 To undo these hierarchical conceptions of the novel and the nation, this book considers how gender and nationhood were ideological battlegrounds in the search for identity and self-expression, as evidenced in the novels published from 1789 to the ascent of Realism around 1830.

The French Revolution represents a pivotal and complex moment within the history of personhood in France. The move away from hereditary←2 | 3→ class-based determinants of identity shifted the foundations of society and reformulated social bonds between people: the beheading of the king transferred unity from the national père [father] to the patrie [fatherland]. The theoretical individualism of the eighteenth-century could now be played out in real life and have its boundaries tested, the psychological effects and structural limitations of which were a source of continual conflict. This new formulation of identity was founded upon a violent severing of long-established links to family and land, which left an entire generation disconnected from their past lives. In contrast, the composition of the emerging French nation was rooted in the binary of gender difference; its legislation outlined specific national duties for men and women and allocated separate spheres of activity to them: the masculine public sphere and the feminine private sphere. This tense co-existence of individual freedom and determinism and the melancholia it provoked produced the mal du siècle [malady of the century]. This psychological condition preoccupied Romantic writers, who experienced exile and alienation from France’s new regime. Their writings attest to how the individual and the nation were interdependent and conflicting concepts. Far from the novel writing out the totalizing boundaries of the nation, this book reveals how the novelistic form questions, pushes against and transgresses its national and gendered limitations.

Staël’s and Duras’s personal biographies meant that they acutely suffered the effects of France’s post-1789 social transformation, particularly in its consequences for individual subjectivity. As my analysis will show, these instances of exile, losses of close friends and family and a withdrawal of status in gender, national and class terms were similarly points of departure for their writings.6 These shared experiences were ‘a←3 | 4→ source of melancholy’, as Peter Fritzsche notes, but they ‘also prompted a search for new ways to understand difference’, which had creative and cultural advantages.7 Facing hostilities in France because of their identities whilst being welcomed in foreign England threw into sharp relief the myth of nations existing as eternally cohesive and unique entities. The experience of exile breaks down the boundaries that nations construct because it presents a rupture between the past nationally defined self, from which the individual is now excluded, and the present deracinated self. The illusion of selfhood as a unified, stable concept and the nation’s←4 | 5→ composition as a constantly changing entity become apparent: the lines between self and other effectively become blurred. Staël and Duras adopt a variety of fictional positions to act out this alienation from France and detachment from their past lives. I, thus, contend that the two authors articulated the generational trauma of the extended Revolutionary period by writing the self through agents and sites of otherness, in terms that evidence a dialectical relationship between sameness and difference. Across their works, Staël and Duras develop a fluid and relational model of selfhood: a Romantic selfhood.

The term Romantic is inherently difficult to define; the transience it supposes means that the boundaries of generic, thematic and temporal inclusion within its associated movement Romanticism are excessively flexible. Within the French tradition, D. G. Charlton acknowledges ‘the astonishing breadth of [the Romantics’] concerns and the sheer diversity of literary, intellectual and artistic forms’ they employed. The Romantic era he establishes is bookended by Staël’s first published work Lettres sur les ouvrages et le caractère de J. J. Rousseau (1788) and the posthumous appearance of Victor Hugo’s Dieu (1891).8 Finding a broad range of practitioners, each with their own interpretation of the term, and covering a century in which France continually remodelled itself means that Romanticism is characterized by its very diversity. The task of defining Romantic is problematized further by the French tradition’s complex relationship to other Romanticisms, notably the English and German variations, which emerged first and nourished subsequent national iterations. Staël’s De l’Allemagne locates Romanticism’s roots abroad, which attributes a firmly transnational dimension to her application of its principles, capturing both French specificity and European universality. To speak of a pan-European Romanticism is no less challenging: Lilian Furst views the tradition as ‘too large, too complex, and above all, too elastic to be captured in some scholarly butterfly-net’, whilst Michael Ferber resorts to identifying a broad list of ‘eight or ten “norms”’ that are represented←5 | 6→ across the European context.9 Romanticism, it would seem, resists any boundary that seeks to contain it. Indeed, as Duras wrote in 1824: ‘la définition du romantique, c’est d’être indéfinissable’ [the definition of Romantic is to be indefinable].10

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 240

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788742085

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788742092

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788742108

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788742115

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13158

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (November)

- Keywords

- Gender Nationhood Romanticism

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. XVIII, 240 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG