Learning second language pragmatics beyond traditional contexts

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Second language pragmatics across contexts: An introduction (Ariadna Sánchez-Hernández / Ana Herraiz-Martínez)

- Section I: Technology-mediated contexts

- Chapter 1. Pragmatics in technology-mediated contexts (Marta González-Lloret)

- Chapter 2. Pragmatic development via CMC-based data-driven instruction: Chinese sentence final particles (Qiong Li / Naoko Taguchi / Xiaofei Tang)

- Chapter 3. Politeness in first and follow-up emails to faculty: Openings and closings (Patricia Salazar-Campillo / Victòria Codina-Espurz)

- Section II: Emerging institutional settings in the European context

- Chapter 4. A focus on the development of the use of interpersonal pragmatic markers and pragmatic awareness among EMI learners (Jennifer Ament / Júlia Barón Parés / Carmen Pérez-Vidal)

- Chapter 5. English-medium instruction and functional adequacy in L2 writing (Ana Herraiz-Martinez / Eva Alcón-Soler)

- Chapter 6. CLIL students’ pragmatic competence: a comparison between naturally occurring and elicited requests (Nashwa Nashaat-Sobhy / Ana Llinares)

- Chapter 7. Learning pragmatics in the multilingual classroom: Exploring multicompetence across types of discourse-pragmatic markers (Sofía Martín-Laguna)

- Section III: Study abroad contexts

- Chapter 8. Development of pragmatic competence in L2 Chinese study abroad (Feng Xiao)

- Chapter 9. Becoming me in the L2: Sociopragmatic development as an index of emerging core identity in a Study Abroad context (Anne Marie Devlin)

- Section IV: Natural contexts

- Chapter 10. Students, family members or workers?: Insights into the au pair experience from a sociopragmatic perspective (Annarita Magliacane)

- Chapter 11. Assessing the impact of extramural media contact on the foreign-language pragmatic competence and awareness of English philology students in Spain (Richard Nightingale / Adrián Pla)

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Index

Acknowledgments

As members of the LAELA (Lingüística Aplicada a l’Ensenyament de la Llengua Anglesa) research group at Universitat Jaume I (Castellón, Spain), we would like to acknowledge that this study is part of research projects funded by (a) the Spanish Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (FFI2016-78584-P), and (b) the Universitat Jaume I (P1·1B2015-20), (c) Projectes d’Innovació Educativa de la Unitat de Suport Educatiu 3457/17.

ARIADNA SÁNCHEZ-HERNÁNDEZ AND ANA HERRAIZ-MARTÍNEZ (UNIVERSITAT JAUME I)

Second language pragmatics across contexts: An introduction

Pragmatics is broadly defined as the appropriate use of language according to the context. The centrality of context in the acquisition of second language (L2) pragmatic competence has long been acknowledged (see Taguchi, 2015 for a discussion), since early theories of pragmatic learning that highlighted the key role of saliency of input (Schmidt, 1990), of acculturation to the context (Schumann, 1978), and of socialization with members of the speech community (Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986), to more recent dynamic-complex approaches (see Taguchi, 2012 for a discussion) proposing that L2 pragmatic development is a complex and non-linear process shaped by the interplay between contextual factors and learners’ individual differences. Different contexts vary in the type of opportunities they afford for pragmatic practice, which are shaped by the type of input available, the amount and nature of the possibilities for interaction, and the output required (Pérez-Vidal, 2014). In turn, such specific conditions determine the pragmalinguistic choices available in the given context, as well as the sociopragmatic aspects a speaker needs to know to appropriately communicate.

Traditionally, L2 pragmatic learning has been investigated in foreign language (e.g. Alcón-Soler & Martínez-Flor, 2008), second language (e.g. Taguchi, 2012) and study abroad contexts (e.g. Collentine & Freed, 2004; Kinginger, 2013). Nevertheless, in the current era of Globalization and its consequential rise of technology, increased student mobility worldwide, spread of youth immigration with working purposes, and institutional efforts to foster multilingualism, new settings that provide opportunities for pragmatic practice have emerged. In an attempt to readdress the focus of the L2 pragmatics field towards the key role of context, the volume Learning second language pragmatics beyond traditional contexts moves beyond the traditional distinction of ← 9 | 10 → foreign and second language contexts to account for contexts that are currently paramount in the study of L2 pragmatics. More particularly, the volume is organized into 4 main sections, each section dealing with a specific setting: (i) technology-mediated contexts, (ii) emerging institutional contexts in the European context, (iii) study abroad contexts, and (iv) natural contexts.

Following the present introduction, which frames the series of papers included in the volume within the different key contexts, the volume begins with Section I, Technology-mediated contexts, which includes three chapters on L2 pragmatic acquisition through the use of technology. Not only language students, but also individuals all over the world nowadays need to learn how to be pragmatically appropriate in contexts that have emerged in the current era of Globalisation, such as computer mediated communication (e.g. emails, online forums, social networks), text messaging, online learning platforms, or virtual games. The section begins with Chapter 1, a theoretical chapter by González-Lloret in which she provides an overview of research dealing with L2 pragmatics mediated by technology, and proposes ways in which technology-mediated tools can be integrated in the language classroom to enhance L2 pragmatic learning. In chapter 2, Li, Taguchi and Tang explore L2 learners’ pragmatic development in terms of four Chinese final-sentence particles through computer-mediated communication (CMC) and data-driven instruction. In a similar vein, in the third chapter, Salazar-Campillo and Codina-Espurz examine the pragmalinguistic patterns in openings and closings of follow-up requestive emails sent to lecturers by native speakers of Spanish.

Section II, Emerging instructional settings in the European context, continues with a series of investigations on students’ L2 pragmatic competence in instructed settings that combine content and language learning. The effort to boost multilingualism has led European institutions to promote educational programs that use an additional language (mainly English) as the medium of instruction for non-language subjects with the dual aim of learning content along with an additional or second language. At the higher education level, such programs are referred to as English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI). Addressing this context, in chapter 4, Ament, Pérez-Vidal and Barón-Parés explore ← 10 | 11 → the effects of EMI for the acquisition of pragmatic markers, while Herraiz-Martínez and Alcón-Soler, in chapter 5, focus on functional adequacy in L2 writing. Moving on to the secondary-school level, in chapter 6, Nashaat-Sobhy and Llinares present a study in which they compare naturally occurring and elicited requests in a Content-Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) setting in Spain. Also at the secondary-school level, Martín-Laguna closes the second section with chapter 7, which explores pragmatic markers in a multilingual classroom.

Section III, Study abroad contexts, deals with those instructed temporary stays in a country in which L2 students not only have the opportunity to acquire the language of the community but also to learn about its sociocultural values. Their particularity lies in the fact that the L2 is acquired both from instruction in an educational environment, and from interactions with target language users outside of class, and therefore the role of individual variables is paramount. This section includes two contributions. In chapter 8, Xiao reports a study on the development of pragmatic adaptation in learners of L2 Chinese and explores whether this development is affected by proficiency and social contact. Moving on to Ireland as the study abroad context, Devlin, in chapter 9, investigates the role of interaction during study abroad experiences on sociopragmatic variation patterns, and how this shapes second language identities of a group of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers from different European countries.

Finally, the fourth section, Natural acquisition contexts, involves two chapters dealing with uninstructed settings where informal and implicit learning of L2 pragmatic competence takes place through observation and direct participation in social practices. Examples of natural contexts include the workplace, home placements, service encounters, the media, or business meetings. For instance, in chapter 10, Magliacane focuses on the effects of an au pair experience in Ireland by analyzing the sociopragmatic development of pragmatic markers in conversation. Nightingale and Pla close the series of contributions with chapter 11, in which they assess the impact of extramural media contact with English-language TV series on Spanish undergraduate students’ pragmatic competence and awareness. ← 11 | 12 →

The volume Learning second language pragmatics beyond traditional contexts is designed to be relevant for researchers in the wider field of second language acquisition, and in the particular area of L2 pragmatics. Additionally, it is of interest to foreign and second language teachers both at the secondary and tertiary level, as well as to study-abroad coordinators. All in all, the collection of papers highlights the vast amount of opportunities individuals have in the current era of Globalization to acquire L2 pragmatic ability. The contributors to the volume are from around the word, and include internationally-renowned scholars as well as young researchers who bring fresh ideas to the field. They focus on different L2s (mainly English, Spanish, and Chinese), and include participants of different ages that range from secondary-school students to adults in the workplace. Moreover, the contributions address a wide range of pragmatic features, from more traditional foci such as speech acts, to more current ones such as holistic approaches to pragmatic ability. With this, we hope the volume contributes to the field of L2 pragmatics and sets new perspectives and future lines of research.

References

Alcón-Soler, Eva / Martínez-Flor, Alicia. 2008. Investigating pragmatics in foreign language learning, teaching and testing. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Collentine, Joseph / Freed, Barbara (Eds.) 2004. Learning context and its effects on second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition. 26, 153–171.

Kinginger, Celeste. 2013. Social and cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad. Amsterdam/New York: John Benjamins.

Pérez-Vidal, Carmen (Ed.) 2014. Language acquisition in study abroad and formal instruction contexts. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Schieffelin, Bambi / Ochs, Elinor. 1986. Language Socialization across Cultures (Studies in the social and cultural foundations of language; Vol. 3). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ← 12 | 13 →

Schmidt, Richard. 1993. Consciousness, learning and interlanguage pragmatics. In G. Kasper / S. Blum-Kulka (Eds) Interlanguage Pragmatics. New York: Oxford University Press, 21–42.

Schumann, John H. 1978. The pidginization process: A model for second language acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Taguchi, Naoko. 2015. Contextually speaking: A survey of pragmatics learning abroad, in class and online. System. 48, 3–20.

Taguchi, Naoko. 2012. Context, individual differences and pragmatic competence. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. ← 13 | 14 →

Section I: Technology-mediated contexts

MARTA GONZÁLEZ-LLORET (HAWAI’ I MANOA)

Chapter 1. Pragmatics in technology-mediated contexts

This chapter calls to mind the importance that learning to be pragmatically appropriate in a second or other language (L2) has in our globalized and increasingly multimodal and multilingual world where much of our communication is mediated by technologies. It suggests that the second or foreign language classroom can be an optimal space to help learners develop their L2 pragmatic competence through the use of technologies. This chapter reviews the existing research on technology-mediated L2 pragmatics, a subfield of interlanguage/L2 pragmatics, to summarize the field, concentrating on studies that have focused on the learning or development of pragmatic features. Innovations such as email, chats, video/audio conferencing tools, synthetic environments, place-based games, and social networks have been investigated for their potential to engage learners in L2 pragmatics. This chapter evaluates how technology has influenced L2 pragmatics and offers suggestions for its incorporation in the language classroom. Finally, this chapter proposes how the field can move forward and what we can expect if we glimpse into the future of technology-mediated L2 pragmatics.

Introduction

In an increasingly globalized world in which multilingualism is “a normal and unremarkable necessity of everyday life for the majority of the world’s population” (Romaine, 2008: 385), being able to interact with others is an essential life skill. However, being multilingual is usually equated with being able to speak a language, that is, to acquire ← 17 | 18 → language fluency, accuracy and complexity. We know, however that being a competent speaker of a language involves more than being fluent. A capable speaker needs to engage in appropriate language use to effectively accomplish a communicative act. A speaker that is grammatically competent but inappropriate will be regarded as impolite or unfriendly (Thomas, 1983) and this may have critical consequences, especially in some situations such as business interactions, job applications, interviews, etc. As Björkman states “the aim in real high-stakes interaction is to communicate in a practical and functional fashion and achieve the desired outcome. In such settings, one needs to acquire an appropriate pragmatic competence to achieve effectiveness in communication” (2011: 923). However, in spite of pragmatic competence being crucial for communication, it holds a small space in language teaching curriculums.

In addition to a growing multilingual world, students need to be prepared for a workforce (and society) in which much of our communication is mediated by technologies. Gonglewski and DuBravac (2006) pointed out that authentic electronic discourses, modes of communication, and the engagement in digital communities are essential to prepare students for a successful career and life in a technology-saturated world. Being pragmatically appropriate when communicating through technology is crucial for the development and maintenance of relationships, and although a lot of our technology-mediated contexts1 are familiar to us, the cyberpragmatics (Yus, 2013) of each medium (i.e., the pragmatic norms and conventions) are not the same as in face-to-face interactions and they also vary among tools.

This chapter advocates that the language classroom is an excellent space to integrate the learning of L2 pragmatics and that this can be done by incorporating technologies that mediate communication and expose our learners to a variety of contexts, interlocutors and digital and virtual spaces. ← 18 | 19 →

Research on Technology-mediated L2 Pragmatics

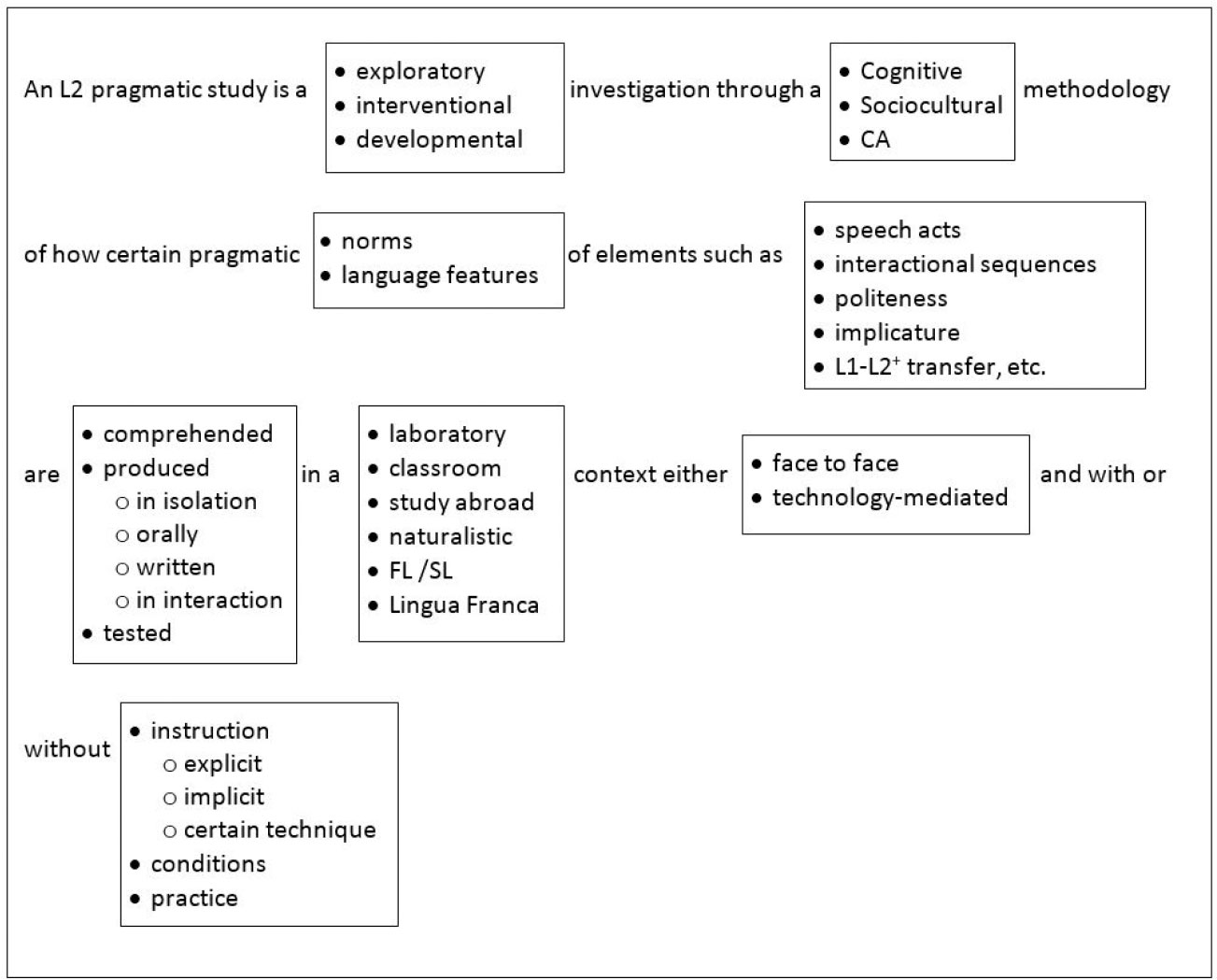

The field of L2 pragmatics is large and there is a wide variety of studies focusing on different pragmalinguistic features as well as sociopragmatic norms within a variety of contexts. In addition, L2 pragmatic studies have employed different methodologies to investigate a variety of topics such as comprehension and production of pragmatic features, either when learned in naturalistic settings or in classroom settings through instruction and practice. Technology and technology-mediated contexts are an additional variable on the complexity to these studies (See Table 1.1. for possible research designs).

Table 1.1: Technology-mediated L2 pragmatic research designs.

Given that the use of technologies is a relatively new focus within L2 pragmatics, many of the studies to date are exploratory in nature, that is, ← 19 | 20 → they investigate how learners engage with others or with the medium, focusing on pragmatic norms or pragmalinguistic features. There are also investigations more experimental in nature that explore an intervention (e.g., explicit teaching, awareness-raising activity, computerized practice) to explore what happens after that intervention, usually with an experimental-control group design (see Li, Taguchi and Tang, this volume), and a third group of studies, longitudinal in nature, which investigate whether L2 pragmatic learning (sociopragmatic or pragmalinguistic) occurs when technologies are part of the learning experience. It is also important to mention that technology and L2 pragmatics research intersect in investigations that take advantage of technology as a research tool to gather data but in which technology is not an integral part of the communicative context (e.g. Taguchi, 2013 on comprehension of implicature). Although these studies are of great value to understand L2 pragmatics, they fall outside of the scope of this chapter.

Details

- Pages

- 376

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034334372

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034334389

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034334396

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034334402

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14949

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (January)

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018. 376 pp., 1 fig. b/w, 60 tables, 19 graphs

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG