Becoming TransGerman

Cultural Identity Beyond Geography

Summary

The volume engages the multifaceted nature of «trans»– and a Germanness that defies geography – to explore how Germans and Germany are increasingly situated «beyond» limits. Collectively, these investigations reveal a radical discourse of Germanness, a discourse with significant implications for historical and contemporary German self-understanding.The book asks the following: What is German identity beyond geography? And what are the promises and perils for Germany, and German identity, in becoming transGerman?

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- 1 Introduction: What Is ‘Becoming TransGerman’? (Thomas O. Haakenson)

- 2 What Can Trans Do? (Tirza True Latimer)

- 3 Going Beyond Spatial and Cultural Fixities Through Ernst Reuter’s Photographic Encounters in Turkey (Barış Ülker)

- Contextualizing Reuter’s Biography through Mobilities

- Interpretation of Modern Urbanization

- Representing Urban Housing

- Representing Urban Infrastructure

- Conclusion

- 4 Autopsy, Authority and Affect: Body Voyaging in Anatomical Fairy Tales from 1920s–1940s Germany (Kristen Ann Ehrenberger)

- Fritz Kahn’s Technological Fairy Tales

- Journey Through a Giant with Heumann-Heilmittel

- TransGerman Body Voyages

- 5 Mit Schmetterlingen denken. Der transvestitische Mensch in Magnus Hirschfelds Bilderteil zur Geschlechtskunde [Thinking with Butterflies: Transvestite Humans in Magnus Hirschfeld’s Illustrated Volume Sexual Science] (Josch Hoenes)

- Von den Transvestiten zum transvestitischen Menschen

- Zur Rezeption Hirschfelds

- Mit Schmetterlingen denken

- Der Schmetterling als Wissenschaftsbild und das Wesen des Transvestitismus

- Der Bilderteil der Geschlechtskunde

- Der transvestitische Mensch

- Weibliche Männlichkeit, Frauen als Männer und Männer, die als Frauen arbeiten

- Das erzwungene Geschlecht: Soldaten und Herrscher

- Die Transvestiten

- 6 TransGerman Experiences in Southern Brazil: The Stutzer Family in Blumenau, 1885–1887 (Ute Ritz-Deutch)

- 7 Transnational Dada and the Politics of Postcolonialism (Thomas O. Haakenson)

- 8 The Archive and Writing (German) Film History (Nichole M. Neuman)

- Writing a National Film History

- A ‘Los Angeles Collection’ in a Berlin Archive

- 9 A Ghostly Matter: Almanya: Welcome to Germany as Transnational Feminist Film Praxis (Mine Eren)

- Framing Sights and Sounds of Transnationalism

- The Turkish Guest Worker: How German Is She?

- Wende Children: Who or What Are We?

- Conclusion

- 10 Instructional Visions: German Visual Messages to the First Generation of Turkish Guest Workers (Jennifer Miller)

- Introduction

- Contemporary Context

- Historical Legacy

- The Invitation

- Words of Welcome

- The Crises of 2015–2016 in Perspective

- 11 TransGerman Drag: Travestie für Deutschland, Homonationalisms and Transgender Citizenship (Anson Koch-Rein)

- The Alternative für Deutschland and Homonationalisms

- Travestie, Translation, TransGerman

- Marianne, Homonationalism, and the Politics of Drag

- TfD Posters and Transgender Citizenship

- Photography and Transgender Visibility

- Beyond ‘Victims’ or ‘Mascots’

- Conclusion

- 12 Berlin Workshop Fifth Anniversary Discussion: Why ‘Becoming TransGerman’ Matters Now More Than Ever (Deborah Barton / Karin Goihl / Thomas O. Haakenson / Carol Hager / Tirza True Latimer)

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series index

Barış Ülker, ‘Going Beyond Spatial and Cultural Fixities Through Ernst Reuter’s Photographic Encounters in Turkey’

Figure 3.1: Ernst Reuter in tailcoat on the birthday of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1936 (Landesarchiv Berlin, E Rep. 200–221, Nr. 278).

Figure 3.2: Street in Ankara, around 1938 (Landesarchiv Berlin, E Rep. 200–221, Nr. 339).

Figure 3.3: Street scene in Turkey, around 1938 (Landesarchiv Berlin, E Rep. 200–221, Nr. 1149).

Kristen Ann Ehrenberger, ‘Autopsy, Authority and Affect: Body Voyaging in Anatomical Fairy Tales from 1920s–1940s Germany’

Figure 4.1: ‘Fairy tale on the bloodstream. I. Entry into a cave-like gland with idealized cell-landscape’ (courtesy of Thilo Debschitz).

Figure 4.2: ‘Fairy tale on the bloodstream. III. In the paternoster elevator of the venous valves’ (courtesy of Thilo Debschitz).

Figure 4.3: ‘Our giant has hemorrhoids’ (courtesy of the author).

Figure 4.4: ‘There is the pain center!’ (courtesy of the author).

Figure 4.5: ‘Present during an asthma attack’ (courtesy of the author). ← vii | viii →

Josch Hoenes, ‘Mit Schmetterlingen denken. Der transvestitische Mensch in Magnus Hirschfelds Bilderteil zur Geschlechtskunde’ [‘Thinking with Butterflies: Transvestite Humans in Magnus Hirschfeld’s Illustrated Volume Sexual Science’]

Figure 5.1: Schmetterling Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld zu Ehren benannt.

Figure 5.2: Statue von Leonardo da Vinci (l) und Apollo (r) in Hirschfelds Kapitel Der androgyne und transvestitische Mensch.

Figure 5.3: Frau als Richterin (l) und Försterin in Baden (r).

Figure 5.4: Frauen als Männer.

Figure 5.5: Männer, die als Frauen arbeiten (l); Karikatur auf Frauen- und Männermode (r).

Figure 5.6: Femininer Soldat A., der in Frauenkleidern desertierte.

Figure 5.7: Partieller Transvestismus eines femininen Tänzers.

Ute Ritz-Deutch, ‘TransGerman Experiences in Southern Brazil: The Stutzer Family in Blumenau, 1885–1887’

Figure 6.1: The German colony Blumenau a decade after its founding in 1850. Woodcut from Tschudi’s Reisen durch Südamerika.

Figure 6.2: Charakterlandschaft am Itajahy (Indaiapalme). Woodcut of a typical landscape of the Itajaí valley near Blumenau from Tschudi’s Reisen durch Südamerika.

Figure 6.3: Portrait of Therese Stutzer, frontispiece in Gustav Stutzer’s In Deutschland und Brasilien. ← viii | ix →

Figure 6.4: The radiant sun dominates the book cover of Therese Stutzer’s Am Rande des Brasilianischen Urwaldes (1980 edition).

Figure 6.5: Book cover, woodcut of Tschudi’s Reisen durch Südamerika.

Figure 6.6: The dark green book cover speaks to the dangers of the rainforest in Wettstein’s Durch den Brasilianischen Urwald.

Figure 6.7: Blumenau Landungs und Stadtplatz. Blumenau Boat Landing and Downtown from Tschudi’s Reisen durch Südamerika.

Thomas O. Haakenson, ‘Transnational Dada and the Politics of Postcolonialism’

Figure 7.1: Photograph from the first International Congress of African Cultures, 1962. Tzara is most likely the individual in the middle of the photograph with the white hair, wearing glasses and a suit. (Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art in Zimbabwe).

Figure 7.2: The program for ‘Manifestation Dada’ as it appeared inside issue 7 of Dada, titled Dadaphone (Paris 1920) (courtesy of the Collection Chancellerie des Universités de Paris, Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris, Fonds Tzara).

Figure 7.3: Dadaglobe project request letter signed by Tristan Tzara, Francis Picabia, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Walter Serner (c. 8 November 1920) (front view) (courtesy of the Collection Chancellerie des Universités de Paris, Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris, Fonds Tzara). ← ix | x →

Figure 7.4: Portrait of Tristan Tzara (c.1920), which appears as plate 155 in the Dada Reconstructed exhibition catalog (courtesy of the Collection Chancellerie des Universités de Paris, Bibliothèque, Littéraire Jacques Doucet, Paris, Fonds Tzara).

Nichole M. Neuman, ‘The Archive and Writing (German) Film History’

Figure 8.1: Still from LA-Sammlung film Charleys Onkel [Charley’s Uncle], which shows the Rotstich or color fading that can occur on film stock (courtesy of the author).

Figure 8.2: Corroded emulsion on film stock of LA-Sammlung film Sauerbruch – Das war mein Leben (Silberveränderung [a chemical reaction involving the emulsion]) (courtesy of the author).

Figure 8.3: A page from a La Tosca Hausprogramm advertises the double feature of the German Heimatfilm, Grün ist die Heide (Deppe 1951) and Föhn [The White Hell of Pitz Palu] (Hansen 1950). Source: Deutsche Kinemathek.

Mine Eren, ‘A Ghostly Matter: Almanya: Welcome to Germany as Transnational Feminist Film Praxis’

Figure 9.1: Yasemin Şamdereli’s female protagonist Canan (Aylin Tezel) in final scene in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film). ← x | xi →

Figure 9.2: The old house in the Turkish Heimat and three generations of women in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film).

Figure 9.3: Transnational localities presented through a vintage view-master in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film).

Figure 9.4: Transnational localities presented through a vintage view-master in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film).

Figure 9.5: Fatma (Lilay Huser) and Hüseyin (Vedat Erincin) exiting a German supermarket in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film).

Figure 9.6: Image of young Fatma (Demet Gül) in a West-German Tante-Emma-Laden in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film).

Figure 9.7: Muhamed (Ercan Karacayli) hugging a giant inflatable Coca-Cola bottle in a supermarket in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film).

Figure 9.8: A shot of consumer products and the grandmother’s overstuffed suitcase in Almanya: Welcome to Germany (2011) (courtesy of Roxy Film).

Jennifer Miller, ‘Instructional Visions: German Visual Messages to the First Generation of Turkish Guest Workers’

Figure 10.1: ‘Don’t be Late!’ Giacomo Maturi, Hallo Mustafa! Günter Türk Arkadaşı ile konuşuyor [Hello Mustafa! Gunter speaks with his Turkish colleague].

Figure 10.2: ‘Imagined Riches,’ Maturi, Hallo Mustafa!

Figure 10.3: ‘Confusion over contracts,’ Maturi, Hallo Mustafa! ← xi | xii →

Figure 10.4A and B: ‘How does One go to Germany to Work? Living Conditions in the Federal Republic of Germany.’ Source: İş ve İşçi Bulma Kurumu Genel Müdürlüğü Yayınları [Labor Office Directorate Publication] No 28. Ankara: Mars Matbassı [National Library Ankara], 1963.

Figure 10.5: Would You Like to Get to Know Germany? Source: Helmut Artz, Almanya’yı Tanımak ister misiniz? Wiesbaden: Wiesbadener Graphischer Betriebe, 1965. DOMiD, 977.

Figure 10.6: ‘Today’s Germany,’ printed in 1957, with the publisher’s information is also the note: ‘published at the insistence of the Federal Government of Germany’ Source: DOMiD, K05 052.

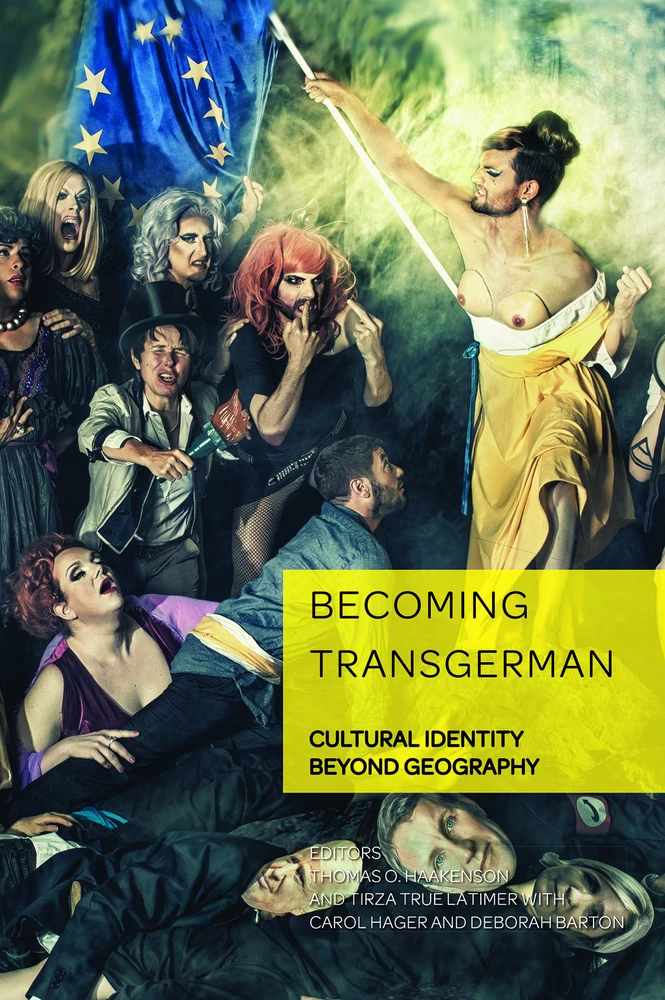

Anson Koch-Rein, ‘TransGerman Drag: Travestie für Deutschland, Homonationalisms and Transgender Citizenship’

Figure 11.1: Steven P. Carnarius, Die Freiheit führt (immer noch) das Volk, 2017 (reproduced with permission from the artist).

Figure 11.2: Steven P. Carnarius, TfD campaign poster of Chandelier D. Brown, 2017 (reproduced with permission from the artist).

Figure 11.3: Steven P. Carnarius, TfD campaign poster of Nic van Dyke, 2017 (reproduced with permission from the artist).

Figure 11.4: Steven P. Carnarius, TfD campaign poster of Kaey, 2017 (reproduced with permission from the artist).

Figure 11.5: Steven P. Carnarius, TfD campaign poster of Renato, 2017 (reproduced with permission from the artist).

1 Introduction: What Is ‘Becoming TransGerman’?

The prefix ‘trans’ has long signified expansive disruptions of borders, limits, and expectations, and the essays contained in this collection, a welcome addition to the German Visual Culture series, celebrate this disruptive potential in multifarious ways. ‘Trans,’ of course, comes from the Latin, meaning ‘beyond,’ ‘across,’ or ‘through.’ The authors featured in Becoming TransGerman: Cultural Identity Beyond Geography address the myriad and interdisciplinary ways in which ‘trans’ signifies as such. Rather than focus, say, on the role of translation in German Studies, or on making disciplinary arguments for an international German Studies, the engagements in this volume focus on the prefix ‘trans’ as it manifests in a wide variety of phenomena with active relationships to visual culture. The authors and essays in Becoming TransGerman thereby speak to and with a growing body of scholarship on the transnational study of German culture by emphasizing the prefix ‘trans’ in that configuration. Equally important, the ‘German’ in Becoming TransGerman is a cultural identity, a ‘Germanness,’ defined more by its fluidity and dynamism than a dogmatic attachment to disciplinary tradition, geographic situation, or national affiliation.

‘Trans’ comes originally from a verb, ‘trare-,’ or ‘to cross,’ a definition that embodies the collected authors’ efforts to situate the Germanness of the traditions, objects, artifacts, and individuals they address as always in the process of negotiating, communicating, and interacting with the supposedly non-German. Some essays address the possibilities of this transGermanness in explicitly national terms, as when individuals or objects from German-speaking countries encounter those from other nation-states to productive, if sometimes also disorienting, ends. Other authors focus specifically on the emergent forms of transGermanness as the result of conscious efforts to rethink traditions or to reconstitute archives. Essays vary in length, demonstrating both the need for deep investigation in some areas and the ← 1 | 2 → desire to look from a broader perspective in others. Taken as a collective, the arguments in the following pages seek to make a case, and make a strong one, that only by thinking beyond, across, or through Germanness is it possible to rethink the past of German culture in service of a reconfigured present and in hopes of a more inclusive future. To become transGerman is a methodological challenge in the present but also an optimistic orientation toward tomorrow.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 326

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781788744263

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788744270

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788744287

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788744294

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13481

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (March)

- Keywords

- trans-Germanness transGerman German self-understanding German identity

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. XII, 326 pp., 24 fig. col., 24 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG