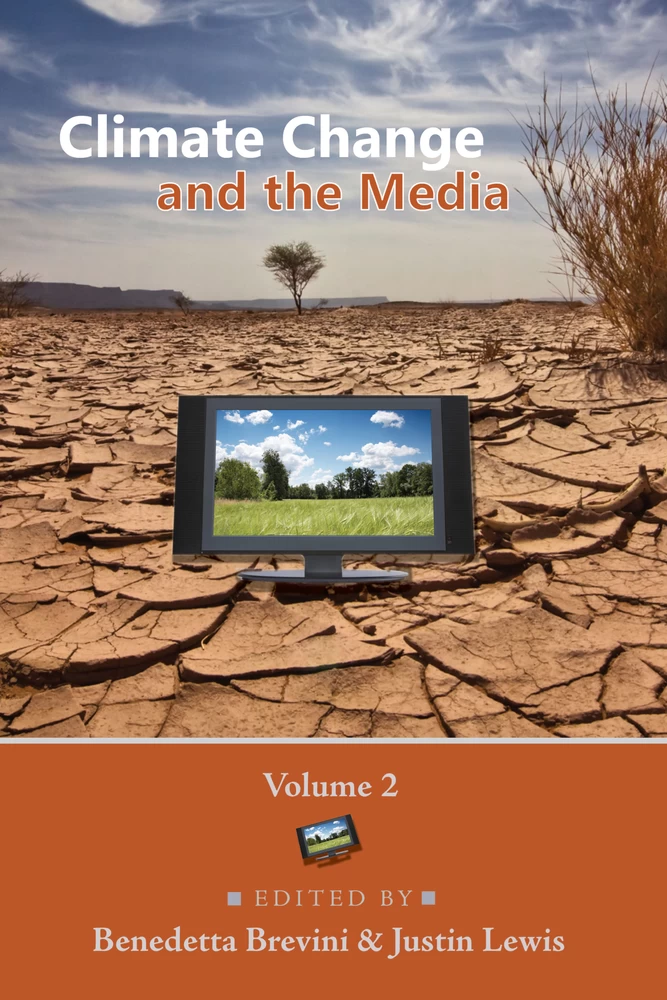

Climate Change and the Media

Volume 2

Summary

How do we explain this colossal global failure? The problem is political rather than scientific: we know the risks and we know how to address them, but we lack the political will to do so. The media are pivotal in this equation: they have the power to set the public and the political agenda. Climate Change and the Media, Volume 2 gathers contributions from a range of international scholars to explore the media’s role in our understanding of the problem and our willingness to take action. Combined, these chapters explain how and why media coverage has, to date, fallen short in communicating both the science and the politics of climate change. They also offer guidance about how the media might shift from being the problem to becoming part of the solution.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Tables

- Figures

- Introduction

- Note

- References

- 1. Public Perceptions of Climate Change (Stuart Capstick / Lorraine Whitmarsh)

- Introduction

- Awareness and Knowledge of Climate Change

- Attitudes to Climate Change

- Communicating Climate Change

- Conclusion

- References

- 2. Ignoring Climate Change, Celebrating Coal: Propaganda and Australian Debates on the Carmichael Mine (Benedetta Brevini / Terry Woronov)

- Methods

- Relational Strategies to Demonize Opposition

- Oxymorons

- Lies

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 3. Global Similarities and Persistent Differences: A Survey of Comparative Studies on Climate Change and Communication (James Painter / Mike S. Schäfer)

- Introduction: A Comparative Perspective on Climate Change Communication

- Global Similarities in Climate Change Reporting

- Persistent Country Differences

- The Role of New Online Players in Different Countries

- Conclusions

- References

- 4. Online Coverage of Paris 2015: The View from the BBC (Neil T. Gavin)

- Introduction

- The Context for Assessing Web Coverage

- The BBC Website During Paris COP21

- Assessing BBC Web Coverage

- Voices on the BBC

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgement

- Notes

- References

- 5. Climate Change in Brazilian Media (Anabela Carvalho / Eloisa Beling Loose)

- Introduction

- Climate Change and Climate Politics in Brazil

- Public Perceptions of Climate Change

- The Brazilian Media System

- Media (Re)constructions of Climate Change

- Reflecting International Agendas and Foreign Voices

- Privileging Official Sources

- Following the Scientific Consensus

- (Re)producing Top-down Techno-managerial Discourses

- Looking Away from Meat—and Other Silences

- News-making and News Consumption

- Conclusions and Future Research

- References

- 6. Environmental Journalism in China: Challenges and Prospects (Sibo Chen)

- Introduction

- Previous Research and Theory

- Reading Chinese Media’s Representations of COP 21

- Discussion and Conclusion

- References

- 7. ‘How Mining Made Australia’: Populist Nostalgia and the Spectre of Climate Change in the Television Documentary Dirty Business (Paolo Magagnoli)

- History, Memory and Climate Change

- A Populist Nostalgia

- Who Controls the Past Controls the Future

- References

- 8. See It Before It’s Too Late? Last-Chance Travel Lists and Climate Change (Lyn McGaurr / Libby Lester)

- Introduction

- Background

- Tourism, the Media and the Public Sphere

- Last-Chance Travel Lists

- Method

- Broad Coding Results

- Linguistic Texts

- Images

- Images and Text

- Great Barrier Reef Case Study

- The Great Barrier Reef in Last-Chance Travel Lists

- Conclusion

- Funding

- References

- 9. The Representation of Risk in the British Press: Comparing Reporting of Climate Change and Terrorism (Victoria Dando)

- Introduction

- Media Realised Risks

- Method

- Reporting Risk: ‘Normalising’ Western Terror Attacks and Distancing Major Climate Risk

- Reporting Effects: Focusing on the West and Ignoring the Rest—the Difference Between Climate Change and Terrorism News

- Discussion

- References

- 10. The Media Produce Climate Change: Fake News, Post-Truth and Journalistic Pollution (Richard Maxwell / Toby Miller)

- The Media Produce Climate Change!

- Which Concept Will Win Out—Post-truth, or the Anthropocene?

- The History of Media Pollution

- What Is to Be Done?

- References

- 11. The Politics of Place: Networking Resistance to Coal Seam Gas Mining (Alana Mann)

- Introduction

- ‘Clean’ Energy and the Emergence of an Oppositional Discourse

- Movement Building Through Communication

- Framing Place Identity

- Conclusion

- References

- Contributors

- Series index

Table 4.1: BBC and ITN late/early evening bulletin containing climate change packages

Table 4.2: BBC web pages featuring climate change

Table 4.3: Unique BBC web pages featuring climate change

Table 4.4: BBC web page news topics.

Table 4.5: BBC broadcast news topics.

Table 4.6a: Voices quoted in web-based stories.

Table 4.6b: Voices quoted in broadcast stories.

Table 6.1: Coverage on climate change and COP by People’s Daily and China Daily.

Table 8.1: Climate change and/or tourism referenced as problems in list introductions.

Table 8.2: Climate change and/or tourism referenced as problems in individual entries.

Table 8.3: Images accompanying entries that mention climate change explicitly or implicitly.

Figure 3.1: Media attention for climate change from 1996 to 2016 in Australia, Canada, Thailand, the UK, the US, India, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Figure 3.2: Volume of coverage of COP21, by country and media type/organisation, 25/11/2016 to 16/12/2016 (many thanks to Dr. Silje Kristiansen).

Figure 3.3: Percentage of articles by media type/organisation covering the negotiations, as major and minor topic.

Figure 9.1: Newspaper coverage of terrorism risk (1999–2012).

Figure 9.2: Newspaper coverage of climate change risk (1999–2012).

Figure 9.3: Effects of terrorism as reported by newspaper (1999–2012).

Figure 9.4: Effects of climate change as reported by newspaper (1999–2012).

The first edition of Climate Change and the Media was published in 2009. That book was written during a period in which the global coverage of climate change had increased significantly (as James Painter and Mike Schafer’s chapter in this volume documents). At the time, it appeared that in many countries, media coverage was, at last, beginning to reflect the scientific consensus about climate change (Zehr, 2009). So, while the 2009 book described the scale of the challenge—not least in a world where the abiding ideology of consumer capitalism is unhelpful in allowing us to understand and address the urgency of the problem—it contained more than a thread of optimism.

A few months after the book was published, the international climate talks in Copenhagen collapsed in disagreement, failing to set meaningful targets or legally binding limits on greenhouse gas emissions. Despite the increasing urgency of the timescale in to prevent significant climate change, hopes of a coherent, global vision to tackle the problem looked increasingly forlorn. Countries were left to continue business as usual, which in most cases meant taking little or no action to reduce emissions. For those scientists, politicians and NGOs who had brought us to the verge of an international agreement, this was a huge setback.

The other biggest news about climate change towards the end of that year was a story give the unoriginal (and inappropriate) sobriquet ‘climategate’, in which sceptics used the hacked emails of climate scientists at the University of East Anglia to claim that the climate change thesis was based on deception. Just when we thought that climate change sceptics were finally being consigned to their place on the wrong side of history, they were back dominating the terms of the debate. So when one of us was invited to take part in a discussion of the media coverage of climate change on the BBC in early 2010, the premise of the discussion—‘Has the media coverage of climate change ← 1 | 2 → been too one-sided?’1—felt like a step backwards. Once again, those arguing that the news media should reflect the scientific consensus—and finally air a serious discussion about what to do reduce the scale and impact of climate change—were put firmly on the defensive.

Although subsequent inquiries into ‘climategate’ exonerated the scientists and found nothing to dislodge the careful weight of scientific evidence, the damage had been done. What might have been a period in which media coverage began to put pressure for action on climate change ended up mired in the same old controversy. Even now, as we enter the era of the Anthropocene, ‘false balance’—where journalists give roughly equal weight to two sides regardless of the weight of evidence—continues to cast a shadow of inaction across the story of anthropogenic climate change.

This period was also one in which the economic crisis caused by a profligate banking system pushed governments around the world towards the pursuit of economic growth at any cost. In the grand narratives that dominate global news, the economic crash of 2008 and the subsequent squeeze on public finances meant that environmental concerns were cast aside—either ignored or attacked as a ‘green tape’ (meddlesome environmental regulations which held back business enterprise). Action on climate change was, once again, postponed—a delay that masks some difficult truths. The worst effects of climate change may be somewhere in the middle distance, but action to prevent it is needed well in advance of any tipping point. And in economies heavily dependent upon fossil fuels, the more economic growth we have, the more likely we are to increase greenhouse gas emissions, pushing any prospect of reducing them to sustainable levels even further beyond our reach (Jackson, 2010). As a consequence, after the initial furore of ‘climategate’, news coverage of climate change began to decline. Various studies have suggested that media coverage of climate change—and environmental issues more generally—peaked between 2007 and 2010—but has declined globally since then (Daly et al., 2015—a decrease documented in the UK by Vicky Dando in this volume). So, for example, Richard Thomas compared two full years of broadcast news in the UK (on the 10 pm weekday flagship bulletins on ITV and BBC) in 2007 and 2014. He tracked the coverage of over 30 topics and issues, and found that while the attention given to the economy increased significantly, environmental issues almost disappeared from news bulletins. Even during the high point of climate change coverage in 2007, the percentage of news time devoted to environmental issues was 2.5% on ITV and 1.6% on the BBC. By 2014, this had dropped to just 0.3% on the BBC and 0.2% on ITV (Lewis, 2015).

Decades of agenda-setting research show that public priorities are often more responsive to prominence in media coverage than they are to ‘real ← 2 | 3 → world’ trends (Lewis, 2001). The lack of media coverage means that while there is a degree of public concern about climate change (as Stuart Capstick and Lorraine Whitmarsh point out in this volume), it scarcely registers as a political issue in most countries. So, for example, it would not be unreasonable for people to assume that the lack of coverage of climate change reflects a diminution of the threat. We have thereby drifted into a cycle of relative silence, where lack of media coverage creates a sense of complacency in both public opinion and political debate.

Meanwhile, the dominance of consumerist discourses in commercial media—most of which are permeated with advertising messages encouraging us to carry on consuming—continues unabated. The ubiquity of advertising—on television, in news, magazines, the internet, social media and indeed, across our urban landscape—is generally regarded as an apolitical (if relentless) intrusion into our cultural environment. But the problem of climate change will not be only fixed by significant technological advances in energy production (Jackson, 2010)—it requires a turn away from the hyper consumption of wealthy nations. In this context, advertising acts as an ideological block on our imaginations, making a more sustainable future seem bleak (Lewis, 2013).

Moving forward to 2017, Post-truth was celebrated as word of the year by the Oxford and Macquarie dictionaries. Defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’ (Oxford Dictionaries, 2016) post-truth politics has thus been identified as a hallmark of the current era in the US and UK, while global politics seems to be threatened by the inescapable spread of fake news, misinformation, all amplified by social media echo chambers (Brevini & Woronov, 2017).

While on the one hand, post-truth politics is triumphing in contemporary political debates, climate change policy, from the moderate—if belated—success of the Cop 21 Paris Agreement, has moved into a new phase dominated by the withdrawal of the United States from an active role in progressive climate politics. In November 2017, at the U.N. climate summit in Bonn, Germany, the Trump administration made its official debut with a forum pushing coal, gas and nuclear power. The panel was entitled ‘The Role of Cleaner and More Efficient Fossil Fuels and Nuclear Power in Climate Mitigation’; the forum was the only official act by the U.S. delegation during the UN climate summit.

Details

- Pages

- X, 190

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433151330

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433154362

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433154379

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433161728

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433153952

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14826

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (October)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. X, 190 pp., 7 b/w ill., 11 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG