Realizing Greater Britain

The South African Constabulary and the Imperial Imposition of the Modern State, 1900−1914

Summary

Combining traditional archival with innovative digital research, this book narrates global integration and imperial governance through individuals, from Boy Scout founder Robert Baden-Powell and imperialist Alfred Milner to Canadian Mountie Sam Steele, Irish doctor Edward Garraway and, foremost, thousands of SAC men. The author argues that opportunistic British agents carried the apparatus of the coercive, legible and bureaucratic modern state across the British Isles, the empire and the world, leaving challenging legacies for successor governments and former subjects to confront.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Usage

- Maps

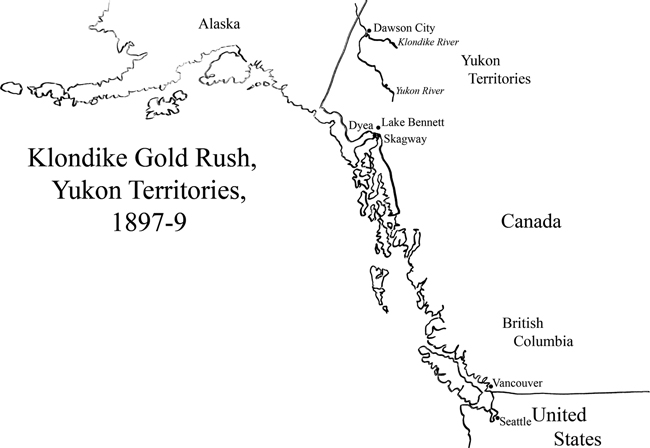

- Prologue: Stampeding Across Borders, 1895–1899

- Introduction: Securing the Empire-State

- Chapter 1 Planning Reconstruction, (Southern Hemisphere) Winter 1900

- Chapter 2 Assembling a British-Imperial Constabulary, 1900–1901

- Chapter 3 Securing Winning Strategies, 1901–1902

- Chapter 4 Fighting Frustrations, 1901–1902

- Chapter 5 Establishing the New States, 1902–1903

- Chapter 6 Managing the Colonies, 1903–1907

- Chapter 7 Dispersing Across the World, 1902–1914

- Epilogue: Connecting Greater Britain, 1908–1950s

- Conclusions: The Men of the South African Constabulary

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Internet

Figure 1 Sir Hubert von Herkomer, Robert Baden-Powell, 1903.

Figure 2 Robert Baden-Powell, ‘South African Constabulary’ Uniforms, 1900.

Figure 3 Robert Baden-Powell, Initial SAC Division Map, 1901.

Figure 4 South African Constabulary Journal, 1902.

Figure 5 Robert Baden-Powell, SAC Recruitment Poster, in the Daily Graphic, February 1902.

Figure 6 SAC Troop, photograph, c. 1903.

Figure 7 Photographs from 1913 SAC Association Banquets, 1913.

Table 1 Population of Greater Britain, c. 1901

Table 2 Police to Policed Communities Ratios for Selected ‘British-Imperial’ Police Forces, c. 1901

Table 3 Wartime SAC Officer Regimental Origins

Table 4 SAC Officer ‘Country’ Origins

Table 5 Regional Distribution of Initial Drafts of Troopers Raised in United Kingdom, 1901

I first came across the South African Constabulary in the National Archives in Kew in the summer of 2006. That’s a lifetime ago, relatively speaking – the same length of time to ascend from kindergarten to high school graduation. My thirteen years of research and writing on the men of the South African Constabulary has lasted longer than the eight-year life of the force. It will be strange to leave them in the past.

One never undertakes a research project like this one by oneself. It started as a dissertation at the University of Virginia. Grants and scholarships allowed me to travel to the United Kingdom, South Africa and Canada and within the United States to conduct archival research with my digital camera, and then read those tens of thousands of images back home in Charlottesville, Medford and Melrose. I would like to thank at UVA the Corcoran Department of History, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the Alderman Library Scholars’ Lab and the Raven Society. I would also like to thank the John Anson Kittredge Educational Fund, Lynde and the Harry Bradley Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the International Council for Canadian Studies.

At the University of Virginia, many intellectual mentors assisted me with my thinking on imperial governance and identity formation within the British Empire. While some have passed, retired or moved to other universities, and some remain in Charlottesville, all contributed to this project. Thank you to Steve Schuker, Joe Miller, Krishan Kumar, Guy Ortolano, Ed Lengel, Maya Jasanoff, Lenard Berlanstein, Paul Halliday, Neeti Nair, Ronald Dimberg, Sophia Rosenfeld and Karen Parshall. Kind members of the larger academic community took time to meet with me, answer my correspondence and provide material, including but not limited to Rod MacLeod, Jim Wallace, Tim Jeal, Jeanne Penvenne, Erik Goldstein, Susan Pedersen, Richard Price, Stephen M. Miller, Charles ←xiii | xiv→van Onselen, Tim Parsons, Heather Streets-Salter, Jim Cronin, Arianne Chernock, Richard Nicholson and Alan and Frank Hackney. I thank them. For peers, as graduate students or emerging scholars, I would like to thank James Wilson, Lawrence Hatter, Dana Stefanelli, Chris Loomis, Alex Isaacson, Martin Ohman, Toby Harper, Amanda Behm, Chas Reed and Jill Bender for their sympathetic ears and pens.

Portions of this research were published earlier in Britain and the World and Scientia Militaria – South African Journal of Military Studies and in Vincent Denis and Catherine Denys, eds., Polices d’Empires 18e-19e siècles (Rennes, France: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012). Participants at many conferences and talks have listened to me speak on the South African Constabulary, including the North American, Northeast and Southern Conferences on British Studies, Midwest Victorian Studies Association, North Eastern Workshop on Southern Africa, South Atlantic Studies Forum and CIRSAP Program Conference on Police and Colonial Empires. I thank them for their comments. A special thanks to the Brenthurst Library for permission to reproduce portions of the Hartigan manuscript. Phil Dunshea at Peter Lang graciously assisted me through the publication process.

For the past four years, I have taught at Winchester High School. While I never expected to teach at a public high school 10 miles away from where I grew up when I entered graduate school in 2004, life and work at WHS has been better than I could have imagined. Several members of the staff have assisted me with my queries over the past year in my completion of this book, including Kathy Grace, Paul Hackett, Chris Kurhajetz and Dennis Mahoney. Thanks to the Social Studies department for their support. A special thanks to my two student assistants, Sean Restivo and Liza Kelley. And a hearty thanks to the many students with whom I have interacted. You provide me with the energy and enthusiasm to come to school every morning, excited for the day (well, most days).

←xiv | xv→Finally, I would like to thank my family for inspiring me. To my grandparents, your voices remain within me. To my parents Carl and Karen and my mother-in-law Aviva, I would not have achieved this success without your support and assistance. To dearest Hedda, your guidance, comfort, understanding and love provide a place for me in this world. And to sweet Maya and Abigail, continue to be deep thinkers and reach for the stars.

Melrose, June 2019

Scholars use a number of terms for the same concepts in British, British Imperial and Southern African history. This book will attempt to stay consistent to the below terms throughout.

The British Isles refers to the islands of Great Britain, Ireland and lesser surrounding isles off the northwestern coast of the Eurasian landmass. Great Britain refers to the island off the northwest coast of Europe, containing the political entities of England, Scotland and Wales. Ireland refers to the island just west of Great Britain. And the United Kingdom comprises the state centered on Parliament at Westminster and the Crown in London. The United Kingdom’s government bureaucracy is centered upon Whitehall in London. British finance is centered upon the City of London.

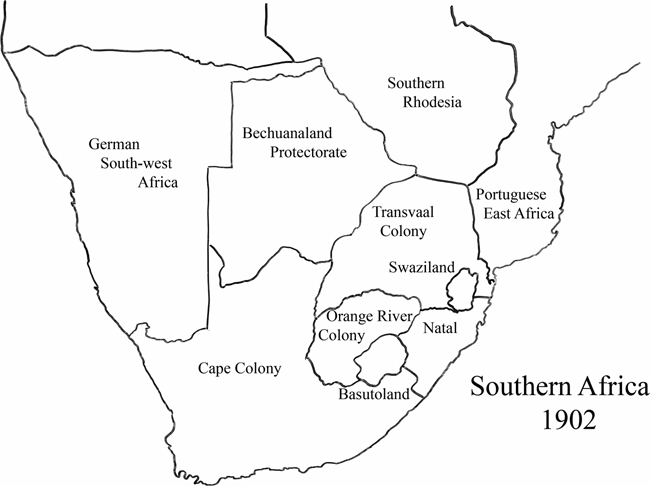

The white, self-governing settler colonies of the British Empire (Canada, Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand, Cape Colony and Natal) officially became known as dominions following the 1907 Imperial Conference. As most of this book deals with the pre-1907 period, it refers to these colonies as settler colonies throughout. Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and the (British) East Africa Protectorate (Kenya), while settler colonies, were never dominions and are therefore not included when the collective term settler colonies is used unless specifically noted.

When referring to the desired, increased relationship between the British Isles and settler colonies, no contemporary spoke of the British World, a recent academic neologism. They rather used the term Greater Britain. So will this book.

Contemporaries referred to southern Africa, the southern-most portion of Africa (today’s South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Zambia) as South Africa. The Union of South Africa (today’s Republic of South Africa) refers to the self-governing dominion of the British Empire created in 1910 from the ←xvii | xviii→British colonies of Cape Colony, Natal, Transvaal Colony and Orange River Colony, generally referred to today as South Africa. For the most part, this book generally uses South Africa as contemporaries did, but occasionally deploys southern Africa to refer to the larger sub-continental region. Whenever referencing the post-1910 dominion, this book uses Union or Union of South Africa. The geography of interior southern Africa is highland, dominated by veldt [grasslands] and kopjes [small hills within the veldt].

The Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek [South African Republic] (ZAR), the independent Boer republic north of the Vaal river, more commonly known as the Transvaal, was annexed by the British Empire as Transvaal Colony in 1900. The region surrounding the city of Johannesburg is the Witwatersrand, also known as the Rand. When referring to the pre-1900 state, this book uses ZAR.

The Oranje-Vrijstaat [Orange Free State] (OFS), the independent Boer republic between the Vaal and Orange rivers, was annexed by the British Empire as the Orange River Colony (ORC) in 1900. With Union, the province became known again as the Orange Free State.

While some scholars have treated the terms Boers (the Dutch word for ‘farmers’) and Afrikaners as interchangeable, the descendants of Dutch settlers in South Africa referred to themselves at the turn of the twentieth century as Boers or burghers (the Dutch word for ‘citizens’).1 ←xviii | xix→When referring to the British ‘enemy,’ this book will use Boer. When referring to that same population in peacetime, burgher will be used. Poor, landless Boers, for-hire laborers in a similar social position to Africans, were known as bywoners and looked down upon by respectable burghers. Burghers would come to dorps [villages] to trade and sell goods. The Taal is the dialect of Dutch that became formalized as the Afrikaans language in later decades.

Africans refer to the descendants of the widely diverse inhabitants of southern Africa before the first Europeans settled in the mid-seventeenth century. In addition to their ethnic designation (e.g. Zulu) today, contemporaries referred to them as natives or, more derogatorily, kaffirs. Contemporaries saw them as organized around tribes or, more accurately, chiefdoms.

The South African War between the British Empire and ZAR and OFS (1899–1902) has been known, depending on one’s perspective, the Second Anglo-Boer War, the Boer War, or Second War for Independence. This book sticks with South African War.

The ZAR and OFS militaries were organized in commandos, militia-like units of burghers. Those burghers who continued to fight the British after the capture of the main cities of the ZAR and OFS are referred to as bitter-enders. Those who surrendered to British officials are hands-uppers. Those burghers who joined the British military efforts against the commandos are joiners. The commandos did not recognize neutral burghers.

The British Army set up protected camps to secure burgher and African civilians and to prevent them from supplying commandos. British officials used the designation refugee camps. Contemporary critics ←xix | xx→and Afrikaner nationalists and others since have referred to them as concentration camps. As British intentions were good but very poorly executed, this book refers to them as internment camps to disassociate any connection with the Nazi death camps of the Second World War.

The rank-and-file of the South African Constabulary were known as troopers until February 1904, when their designation changed to constables. To make the distinction clearer, this book refers to the rank-and-file during the war as troopers and in peacetime as constables.

Commonly used abbreviations

←xxi | xxii→ ←xxii | xxiii→1 ‘Afrikaner’ and Afrikaner nationalism developed out of the post-South African War period, as a means to rebuild and unify the burgher community following the approximately 28,000 deaths (14 percent of the pre-war population) in British internment camps during the war and through the political opposition to British High Commissioner Alfred Milner’s reconstruction policies, expressed through the Het Volk political party in Transvaal Colony. In addition, the political and practical motives of writing in an Afrikaans language rather than Dutch and the social changes that occurred in the shift from a rural farming to an urban society contributed to the self-identification as ‘Afrikaner’ and no longer ‘Boer.’ Many ‘Boers’ also continued to see themselves as Dutch. See Helen Dampier, ‘“Everyday Life” in Boer Women’s Testimonies of the Concentration Camps of the South African War, 1899–1902’, in Crime and Empire 1840–1940: Criminal Justice in Local and Global Context, eds. Graeme Dunstall and Barry S. Godfrey (Cullompton, Devon: Willan Publishing, 2005), 202–23; Hermann Giliomee, The Afrikaners: Biography of a People (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003), xix, 254–6; and Isabel Hofmeyr, ‘Building a Nation from Words: Afrikaans Language, Literature and Ethnic Identity, 1902–1924’, in The Politics of Race, Class and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century South Africa, eds. Shula Marks and Stanley Trapido (London: Longman, 1987), 95–123.

Details

- Pages

- XXVI, 382

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788747042

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788747059

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788747066

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788747073

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16787

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (February)

- Keywords

- South African Constabulary Greater Britain imperial policemen

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 201X. XXVi, 382 pp., 7 fig. b/w, 6 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG