Lurleen Burns Wallace

The Power of the First Lady Governor

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

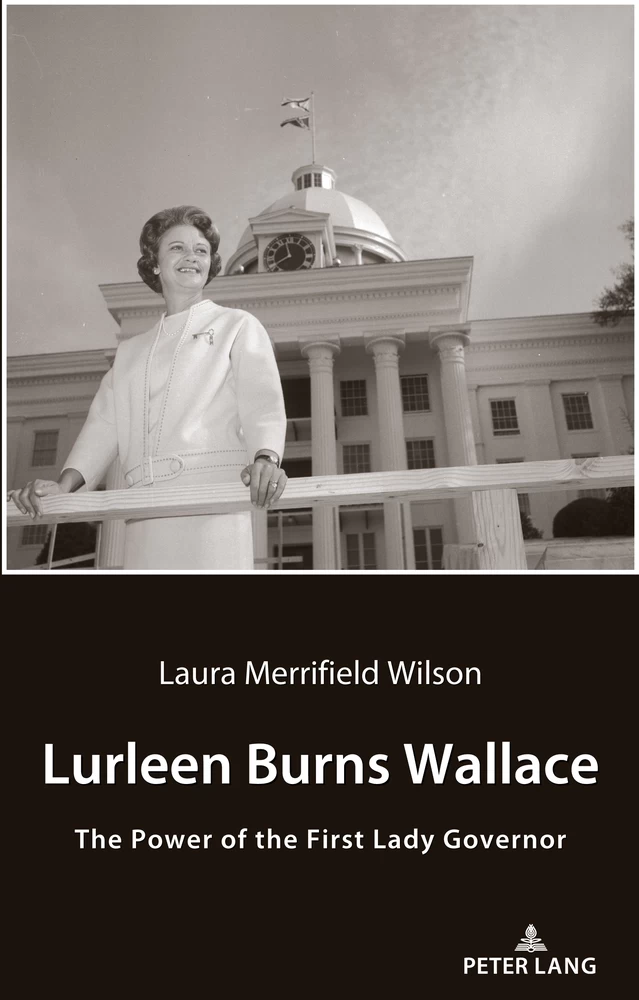

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Get Your Running Shoes On

- 2. Me for Ma

- 3. No Skirt?

- 4. The Governor Is a Mother

- 5. Petticoat Politics

- 6. Health and Hope

- 7. The Parade She Never Wanted

- Bibliography

Figure 1. Lurleen Burrough Burns Wallace as a baby in rural west Alabama.

Figure 2. Lurleen Wallace as a young woman.

Figure 3. Lurleen Wallace holding a turkey she shot.

Figure 4. Stamps distributed during Lurleen Wallace’s campaign for governor.

Figure 9. Governor George C. Wallace and Lurleen Wallace and family.

←ix | x→Figure 11. Official portrait of Lurleen Burns Wallace, 46th governor of Alabama.

I would like to thank everyone who helped me with this project as it developed, including my colleagues at the University of Indianapolis Department of History and Political Science and University of Alabama Department of Gender and Race Studies. I am indebted to everyone who gave me valuable feedback and encouragement, including Lindsey Smith, Terry Hughston, Ishita Chowdhury, Jennifer Joines, Sumi Woo, Andrew Fletcher, Ali Faol, Thomas Beaumont, Dr. Larry Sondhaus, Dr. Jim Fuller, Dr. Ted Frantz, Dr. Daniel Levine, Dr. Elizabeth McKnight, and Dr. Utz McKnight. I especially want to thank Dr. Utz McKnight for his kind support and encouragement. Additionally, I was blessed to work with a fantastic editorial team at the University of Alabama and want to recognize their outstanding work, as well as the helpful reviewers whose great comments immensely improved the project.

A very special thank you to the Governor Albert Brewer, the Honorable Jim Martin, and the wonderful Anita Smith whose kindness and collective insights helped shape the story. Their willingness to speak with me goes above and beyond and for their help, I am truly grateful. Additionally, the Alabama Department of Archives and History provided an invaluable repository of primary sources and their assistance in the research process was greatly appreciated.

←xi | xii→Last but never least, I want to thank my family. For my parents, who supported me and painstakingly read every page, most of them many times over, I am forever grateful. For my husband, who listened to me talk about this project for many years and provided feedback and support, I am so thankful.

This is for all the women who broke barriers in a man’s world and paved the way for women in my generation. Thank you.

Walter Devries: “When you think back through time in Alabama, who are the best

governors this state ever had in terms of accomplishments?”

George Wallace [quickly]: “Oh, George Wallace.”

Walter Devries: “Well, going beyond the …”

George Wallace [even more quickly]: “Lurleen Wallace.”

—George Wallace in an interview with Walter Devries, July 15, 1974.

Long before Jennifer Granholm (governor of Michigan, 2002–2010), Sarah Palin (governor of Alaska, 2006–2009), and Nikki Haley (governor of South Carolina, 2010–present), there was Lurleen Burns Wallace. She was a country girl who loved to hunt and fish with her father and brother while growing up during the Depression in rural west Alabama. Her childhood aspiration was to become a nurse, but at 16 she met and married University of Alabama law student George Corley Wallace and her life took a turn she never could have imagined. Two decades later, she became the First Lady upon George’s election as governor, and the couple and their four children moved in the governor’s mansion. Four years after George won the gubernatorial election, Lurleen herself ran for governor and won in a historic victory.

←1 | 2→Only the third woman ever elected as governor in the US history, she was the first female governor from the deep south and from Alabama: a state that embraces traditional gender roles and, not coincidentally, consistently ranks among the lowest in female political representation. The area is hardly a bastion of feminist progressivism, yet “Mrs. George C. Wallace” (as her campaign promoted her) won the Democratic primaries without a run-off and swept the general election with a whopping 2-to-1 margin. She successfully defeated eight other candidates in the primary elections (including two former governors, a congressional representative, a state attorney general, and a state senator among others) as well as the most formidable Republican competitor since Reconstruction.

Her candidacy was met with ardent supporters and snide critics. Few claimed she was a feminist pioneer, yet many Alabamians adored the warmth and compassion she brought to her position as a candidate and later governor. She connected with people in a way few others could; more importantly, she embraced her role as a wife and mother to inform her decisions. At the same time, critics, primarily outside the state, wrote her off as a proxy candidate and deemed the political apparatus that enabled her election as a joke. She was labeled a “puppet,” a “proxy,” and a “doll” and her capability and qualifications to be governor were frequently challenged.

As her infamous surnamed indicated, Lurleen promised voters a continuation of her husband’s policies, particularly segregation, which Alabama voters heartily approved. She was elected amid an era of intense racial turmoil in an unequivocally conservative Alabama. The national spotlight focused on the painful racial injustices occurring frequently in Birmingham, Montgomery, and elsewhere around the state. Lurleen continued the tradition of her predecessors, waging battles against the federal government mandating the state integrate its public schools. She fought, but lost. Though segregation would finally be dismantled after many years and gubernatorial administrations later, Lurleen failed to prevent the federal courts from ruling in favor of integration, striking down numerous state policies thwarting it.

Her work in mental health reform remains the most cherished and long-lasting part of her legacy. She was the first governor to walk the halls of the sad and dilapidated Bryce Hospital, a mental institution in Tuscaloosa, and determine that such disrepair was unconscionable. Lurleen worked to appropriate more money to mental health institutions throughout the state. Shortly after her death, successor Governor Albert P. Brewer constructed a handful of new facilities and dedicated one to the late governor’s namesake.

←2 | 3→Though she may have been the most politically powerful woman in the state, Lurleen had no personal power over her own body. At the same time, she was losing the fight for segregation, Lurleen was losing another much more personal battle. Just six months into her term as governor in 1967, a small tumor was discovered in her abdominal cavity. Tests confirmed her worst fears, it was cancer.

In fact, this marked the second time the governor had received a cancer diagnosis. Unbeknownst to her, a tumor was extracted from her uterine wall after an emergency cesarean section during the delivery of her youngest daughter in 1961. Her doctors warned her husband, per the custom of the day to inform the man of the home and not the actual patient. George consulted, not with Lurleen, but with his top advisors. It would be best for Lurleen, her doctors concluded, to rest and enjoy the short remainder of her life. George, however, had other plans.

In order to realize his presidential aspirations for the 1968 race, he needed to remain prominent in the political spotlight. His term as governor would end in 1966 but the constitution prevented him from seeking a second consecutive term. Instead, he needed someone in office to support his policies; someone who would allow him to remain in the national spotlight. He needed Lurleen.

For whatever reason, George decided not to inform Lurleen of the cancer developing deep inside her. She first learned of her original cancer diagnosis only four years later in November 1965, the same time George suggested she run for governor. Doctors conducted surgery and, without seeing additional tumors, assured her she was healthy. Unfortunately, the doctors could not detect the cancerous cells still multiplying within her body, and that would yield another growth less than two years later. Because Lurleen was unaware of the cancer in 1961, aggressive and proactive treatment was never pursued. As she mounted an extensive, if exhausting, historic campaign, a uterine cyst the size of an egg swelled inside her; despite desperate attempts to eradicate the malignancy, it continued to grow. Multiple surgeries and treatments from July 1967 through April 1968 failed to stop the cancer as it slowly spread to her colon, abdomen, and lungs.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 224

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433165726

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433165733

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433165740

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433165757

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15100

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (November)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XII, 224 pp., 15 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG