Obscenity and Disruption in the Poetry of Dylan Krieger

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The Landmine in the Garden

- Chapter 2. Obscenities of Religion on the Site of the Body

- Chapter 3. Giving Godhead: Performative Poetics as a Manifestation of Trauma-Induced Inductive Reasoning

- Chapter 4. Dreamland Trash and Autobiographical Cultural Critique

- Chapter 5. The Broken Body as an Epistemological Statement

- Chapter 6. No Ledge Left to Love: The Broken Body on an Astral Scale

- Chapter 7. The Ethical Imperative of The Mother Wart

- Conclusion: First Four Books of Poems

I could not have composed this study of Dylan Krieger’s poetry as I have without a generous provision of access from Grinnell College to its main research hub, Burling Library, and also to Kistle Science Library. Krieger’s poetry is frequently raw, aggressive, and highly performative on its surface, but it is also heavily nuanced and indebted to the complexities of Krieger’s own education. Grinnell College was my source and refuge for researching most of those complexities, in distinct contrast to my former employer of 24 years, the University of Iowa. My thanks go out to Grinnell Professor Mark Christel, Librarian of the College, and Amy Brown, Christine P. Gaunt, Betty Santema, and Chelsea Soderblom, circulation desk supervisors, and to their staff and student workers in Burling and Kistle (although, because this book is controversial, I should emphasize that none of these Grinnellians has previously read any part of this text). Regarding the University of Iowa: apart from the late English professor Linda Bolton; professor David Wittenberg, of English, comparative literature, and cinematic arts; and sociology professor Richard Horwitz, who departed from Iowa in the late 1990s for the University of Rhode Island before semi-retirement in Denver, no one from the University of Iowa merits acknowledgment here. ← ix | x →

* * *

The story of how I first learned of Dylan Krieger’s existence would be comical if it were not such a contemporary period piece: we met as strangers sometime in the early summer of 2016, thrown together by some anonymous algorithm at Instagram. It took me a couple of months to recognize that “dylanwk” was far from just another “friend” I didn’t know. Slowly approaching the new reality of her poetry, I felt an astonishment I hadn’t felt since reading Robert Pinsky’s groundbreaking History of My Heart in 1984 or Allen Ginsberg’s Howl a few years before that at Stanford. Social media can be many things—a marketing platform, a way of keeping up with actual friends, a way of meeting new people, or a way of appraising strangers—but it’s rare in my experience that it offers any real change. With its weird algorithm Instagram altered that. In the past two years, Krieger and I have briefly come to share a publisher (Saint Julian Press in Houston); we have read together once, in Houston on Bastille Day 2017, and I introduced her on June 1, 2017, at her launch party for her first book, Giving Godhead, in her home town of South Bend, Indiana. We correspond rarely. But her work has meant as much to me as any poet I know.

* * *

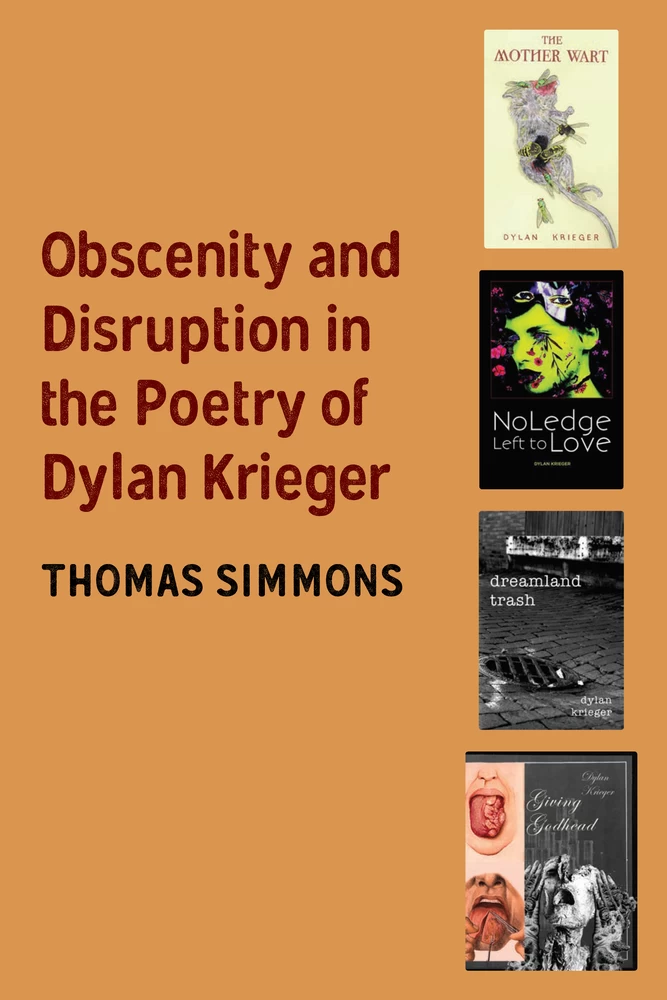

Because Krieger has been writing over the past three years at lightning speed, the first three books I write about here—Giving Godhead, from Delete Press in 2016, dreamland trash, from Saint Julian Press in 2017, and No Ledge Left to Love, the Henry Miller Memorial Library prize-winner for 2017, published by Ping-Pong Free Press in Big Sur, California in 2018—are available to the public, and my citations from them and their page numbers in my endnotes refer to those published versions (I make one exception to this with No Ledge Left to Love, as the manuscript of that book differs in places from the published version, and one of those differences in particular struck me as interesting—but that exception is footnoted). Because I have come to think of the first Krieger collections as a unified quartet, however, the last book—The Mother Wart, just now accepted for publication at an online press (vegetarianalcoholic.com1), with a paperback version scheduled for release on May 12, 2019—is referred to here in its pre-publication manuscript form. While the practical reason for this is obvious, it also seems to me worthwhile to remember how works of poetry begin, and how it is that an author hears them and envisions them at the time of their genesis. Thus this book is about “finished” ← x | xi → work—of the kind we think of when we think of a “book”—with the proviso that no work is ever really finished, even when it leaves the author’s hands or the publisher’s printing house, until the reader encounters it and begins that paradoxical relationship of completion and expansion.

I initially offered Dylan Krieger the chance to review this manuscript in part or in whole, but as it has grown to a full-scale book she has come to the point of view that this is my book, rather than hers, and—whatever my readings of her work and its contexts—they should remain untouched. This is characteristically generous of her, but it also means that any errors of interpretation or citation here are mine alone. I also wish to point out that, while most of the quotations in this book fall under “fair use” guidelines for scholarly publications, I have quoted in their entirety 18 of Krieger’s poems from across her four collections. She (and in one necessary case, Maria Teutsch of Ping-Pong Free Press) have given me permission to do this, for which I am deeply grateful.

I began the first complete draft of Obscenity and Disruption in the Early Poetry of Dylan Krieger during an interesting transition in my own life, and as I return now to that manuscript, making numerous small emendations and corrections, I see how—in my introduction and first two chapters particularly—I am making some intellectual demands on the reader that may not pay off until the third chapter, when Giving Godhead comes front and center and the other three books follow. This is in the nature of a mind that is also making many intellectual and emotional demands on itself. I hope that what may seem like idiosyncrasies or anomalies in the early chapters will become what they should be—the essential underpinnings of the book—at exactly the right moment.2

Even in the early 21st century, some readers will find this book blasphemous and heretical, repeatedly offensive to tenets they hold to be sacred. Krieger and I did not grow up in the “same” religion, but from childhood on we shared a profound sense of violation, particularly bodily violation, on the sanitized altar of the religions in which we were raised. What caught my attention repeatedly, as I first began to research Krieger’s work online back in 2016, was the way in which her violations reflected mine—but also the way in which she fought back far more intensely, more ferociously, than I was able to do. With a handful of exceptional years here and there, and the exception of my six children and my 11 books, I consider my 62.5 years on Earth largely wasted, almost always tangential to a given vector, although a tangent is also a vector, and dedicated to trying to understand the words and points of view of antithetical people. “It seems to me,” then-MIT psychiatrist Eric Chivian ← xi | xii → commented back in spring 1992, regarding my earlier shift from my church to a university professorship, “that you traded one deceptively liberal but authoritarian institution for another”—words it turned out would define my struggle to survive for another two-and-a-half decades. It’s not arrogance but accuracy to observe that most of the people along these tangents did not merit the effort, and I found myself even in late adulthood in flashbacks to early trauma. At one point in 1980, for example, eight weeks before my mother died of untreated melanoma in a Christian Science “care facility,” her practitioner—her “healer”—called a meeting with my fiancée and me and told us that my mother was not “responding to treatment through prayer” because my fiancée and I were sleeping together. I was 24, and my sexuality was responsible for my mother’s death, while the desperate, sadistic practitioner was promoted a few years later to the unparalleled position of Christian Science Teacher.

I view this book as a repayment of a debt, although neither Krieger nor I owe anything to one another. But through my reading of her work, Krieger gave a shape in language to a life I might have lived but did not. At least now, I can witness that. I hope that some, perhaps many of you, who are reading this now, will feel similarly. I would observe that any reader curious about my readings of Krieger’s work might look at my own first and fourth books—The Unseen Shore: Memories of a Christian Science Childhood (1991) and Ghost Man: Reflections on Evolution, Love, and Loss (2001)—as well as Caroline Fraser’s God’s Perfect Child: Living and Dying in the Christian Science Church (2000).

* * *

I have been fortunate to work with Peter Lang Academic Publishing on two earlier books—one in 2010, the other in 2012—and have been grateful for their unusual combination of thoroughness and efficiency in moving my work from manuscript to published book. That efficiency has been especially important to me in the case of Obscenity and Disruption in the Early Poetry of Dylan Krieger, even though “hot off the press” is not a phrase we normally associate with scholarly books about poetry. Meagan Simpson, Acquisitions Editor at Lang, and editorial assistant Liam McLean, deserve great credit for their dedication to this work, grasping its worth early on and moving it expeditiously through production. In Production, Luke McCord has been sensational. I’m most grateful.

Two other colleagues with ties to Saint Julian Press have been, over the past two years, helpful in so many ways that they deserve mention here. ← xii | xiii → Ron Starbuck, publisher of Saint Julian Press, has offered useful advice and encouragement, while Aliki Barnstone, Poet Laureate of Missouri and professor of English and Creative Writing and the University of Missouri, listened patiently to my periodic grousing and moments of doubt that this work would ever finally be completed, and always sent back helpful, hopeful words. Though neither of them has seen the full manuscript of this book, they have nevertheless been a tremendous asset.

—Thomas Simmons

Grinnell, IA

February 14, 2019

Notes

1. Readers dubious about a publisher named “vegetarianalcoholic.com” may have their reasons, but if one looks at Krieger’s publishing record thus far—Delete Press, Saint Julian Press, Henry Miller Memorial Library/Ping-Pong Free Press, and vegetarianalcoholic.com—as well as her dozens of publications of individual poems in both little-known and distinguished alternative periodicals and journals—one sees, not a willful dismissal of the “mainstream,” but rather an embrace of all that “alternative” invites: radical freedom to innovate, engagement with other writers at their own margins, a colloquy of voices and, yes, an implicit critique of all that the status quo implies. Recall that Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Books was as alternative as alternative got in the 1950s, and Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems was City Lights Book Number Four. If my book fails to make clear that Krieger is blazing her unique trail, then my book fails at its heart. I myself misunderstood Krieger’s preference for the alternative venue early on, shortly after Giving Godhead appeared from Delete Press, when I reviewed that book for the New York Times Sunday Book Review. This was not exactly a mistake—it was certainly a thrill for me—but it caused a certain consternation.

2. Readers already familiar with Krieger’s three published collections may, for example, feel that I understate the intrinsic playfulness, whimsy, and ingenious irreverence in Krieger’s work in favor of more wide-ranging and less zany themes. But I deeply admire Krieger’s wit—especially as it’s indebted to those aspects of the Gurlessque that Lara Glenum and Arielle Greenberg touch on in their introductions to Gurlesque, and as Sianne Ngai explores in Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2012) and in her essay on boredom and “stuplimity” in Tom McDonough’s Boredom (London: Whitechapel Gallery/Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), pp. 199–203. The most wonderful single piece of evidence for Krieger’s wit would be the “Notes” at the end of dreamland trash, in which we learn that the poems “novel idea,” “apolitical apology,” and “plantation nation” include references to “Pilgrim’s Progress, Grand Theft Auto, [William Carlos Williams’] “The Red Wheelbarrow,” The Hunchback of Notre Dame, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” Gone with the Wind, and “Black Dark Rainbows” (a poem my friend Nathan Gropp wrote in high school and may be surprised I remember).”

How so complex a relationship between the avant-garde and society came about is a problem we shall try to resolve when we deal with the relations between avant-garde art and fashion, and when we study that special and complex phenomenon called alienation.

—Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde

Just as the play of signifiers contradicts and undermines any claim of possessing a well-defined, conceptually unequivocal, logocentric discourse, so material experience may contradict and undermine the prevalent ideology of a ← 1 | 2 → historical situation.

—Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde

This is the first book-length study of the most exceptional and iconoclastic young poet I know, Dylan Wesley Krieger. In its alienation, its voices, its multiple methodologies, and its complexity, her work manages to be the contemporary heir to Walt Whitman on the one hand and to Allen Ginsberg on the other, but also to Adrienne Rich and, however ironically, to Louise Glück. It is a body of outrage in debt to the Marquis de Sade, and yet at other times coolly brilliant in its theological and philosophical analyses, drawing heavily on Husserlian phenomenology but demonstrating a mastery of western metaphysics from Plato to the present. Its critique of Christianity in the present, or rather, as Peter Bürger says, Christianity in “the prevalent ideology of a historical situation,” is precise and devastating. Just as Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems was charged as “obscene” in 1955, Krieger’s work will surely be labeled that way, but like Ginsberg—whom Krieger references in her “Sacreligion Manifesto” at the conclusion of Giving Godhead—Krieger welcomes the charge: “obscenity” in Krieger’s work is the very nature of the human body and Malraux’s La Condition Humaine, and thus needs to be interrogated, even celebrated, as we learn from her scholarly work on the “Gurlesque” tradition in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.1

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 246

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433166730

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433166747

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433166754

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433166761

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15297

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (July)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2019. XIV, 246 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG