Kurdish Autonomy and U.S. Foreign Policy

Continuity and Change

Summary

In the second section, several contributors explore the Kurdistan Regional Government’s unfulfilled expectations and the fallout from the 2017 independence referendum. Consecutive U.S. administrations have been reluctant to destabilize the region, supported efforts by Turkey to co-opt the KRG, and impeded Kurdish movements in Syria and Turkey.

Finally, the third section analyzes the ways in which Kurdish movements have responded to long-standing patterns of U.S. foreign policy preferences. Here contributors examine Kurdish lobbying efforts in the United States, discuss Kurdish para-diplomacy activities in a comparative context, and frame the YPG/J’s (People’s Protections Units/Women’s Protections Units) and PYD’s (Democratic Union Party) project in Syria. Broader power structures are critically examined by focusing on particular Kurdish movements and their responses to U.S. foreign policy initiatives.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the editors

- About the book

- Advance Praise

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction: Kurdish Autonomy and U.S. Foreign Policy (Vera Eccarius-Kelly/Michael M. Gunter)

- U.S. Foreign Policy and the Kurds

- 1. Non-State Actors as Agents of Foreign Policy: The Case of Kurdistan (Marianna Charountaki)

- 2. Will the United States Ever Support Kurdish Independence? (Michael Rubin)

- 3. U.S. Foreign Policy Towards the Kurdish Movement Under Obama and Trump (Thomas Jeffrey Miley/Güney Yildiz)

- U.S. Foreign Policy and the Kurdistan Region

- 4. U.S. Foreign Policy, Kirkuk, and the Kurds in Postwar Iraq: Business as Usual (Liam Anderson)

- 5. From Aid to Oil: Iraqi Kurdistan’s Dependent Economy (Bilal A. Wahab)

- 6. Trump’s Foreign Policy Toward the Kurds (Michael M. Gunter)

- 7. The Kurds’ Trump Card (David Romano)

- Kurdish Lobbying, Para-Diplomacy and Rojava

- 8. Kurdish Lobbying and Political Activism in the United States (Vera Eccarius-Kelly)

- 9. From Limited Partnership to Strategic Alliance: The Emerging Significance of Kurdish Para-Diplomacy in U.S. Foreign Policy (Haluk Baran Bingöl)

- 10. “Operation Olive Branch”—Did the U.S. Change Its Strategy Toward the YPG? (Eva Savelsberg)

- 11. Imperialism, Revolution, and the Desire to Lecture the Kurds: How Should We (Not) Analyze U.S.-Kurdish Relations (Huseyin Rasit)

- Contributors

- Index

Introduction: Kurdish Autonomy and U.S. Foreign Policy

Vera Eccarius-Kelly and Michael M. Gunter

←0 | 1→This collection critically examines U.S. foreign policy approaches toward Kurds in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria, while also placing Kurdish areas in Iran within the larger context. Of particular interest to the discussion in this volume is how and why U.S. foreign policy approaches toward Kurdish regions and Kurdish movements have either been maintained or modified in recent decades. Three consecutive U.S. administrations anchor the larger foreign policy analysis, namely George W. Bush (2001–2009), Barack Obama (2009–2017), and Donald J. Trump’s first two years in office. While U.S. foreign policy patterns tend to endorse regional stability and the notion of immutability of borders irrespective of party politics in Washington, D.C., several significant developments in Kurdish regions question this premise. Among the central intersections discussed by scholars in this collection are U.S. foreign policy choices toward Kurdish regions during the rise of Islamic State (ISIS), the relationship between the Pentagon and Syrian Kurdish militias, and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’s (KRI) pursuit of the (advisory) Independence Referendum in late 2017.

The contributors in this collection represent a wide range of analytical perspectives informed by their academic training and expertise in political science and international relations (IR), history, sociology, conflict management and issues related to natural resource extraction and state governance. Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that several scholars in this volume disagree with each other over questions of framing and interpretation. The various chapters rely on a wide variety of methodological approaches including comparative case studies and IR analyses as well as theoretical and critical policy discussions. Such diverse approaches, of course, encourage a ←1 | 2→transformation in the ways in which Kurdish movements and Kurdish regions are analyzed within the academy and foreign policy circles.

While U.S. foreign policy toward the divided Kurds has gone through numerous stages,1 it tends to be most often discussed within the constant that non-state actors ultimately take second place to state actors such as Turkey and Iraq, among others. As former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger once cynically explained when the United States pulled its support from Mullah Mustafa Barzani’s Iraqi Kurdish revolt in 1975: “Covert action should not be confused with missionary work.”2 Although Kurdish movements and various Kurdish nationalisms have made impressive strides, David Romano quips in this collection that le plus ça change, le plus c’est la même chose [the more things change, the more they stay the same]. It appears that the overarching pattern in U.S. foreign policy toward the Kurds has essentially remained constant, even during the initial years of the gyrating policies of the rather unconventional Trump administration.

However, several distinguishing factors emerge in this collection that could indicate noteworthy and consequential modifications within U.S. foreign policy analyses toward Kurdish movements and Kurdish regions. U.S. foreign policy toward Kurdish regions is no longer exclusively shaped by regional states such as Turkey or Iraq, but also through new, even if temporary alliances between sub-state/non-state actors and particular structures within the U.S. government. Kurds actively engage in para-diplomatic activities in the international arena, organize grassroots activities in the diaspora and engage professional lobbying firms to advance specific sub-national agendas. In that sense, this collection challenges the assertion that U.S. foreign policy patterns have remained immutable in the region.

The collection is organized into three distinct segments to encourage a larger debate around elements of continuity and change in U.S. foreign policy approaches toward the Kurds in the context of multiple administrations. The first section focuses on “U.S. Foreign Policy and the Kurds” by examining U.S. foreign policy patterns and consequences for Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Syria, but also in Iran, although in a more limited way. In Chapter 1, Marianna Charountaki reminds us that IR theory has to inform our thinking about foreign policy in the international relations system. She asserts that foreign policy has primarily been focused on the state level instead of a more holistic approach that would consider an integrated analysis of specific typologies of non-state entities. That is the expansion of the state level to include the non-state level in foreign policy analysis. The case of the Middle East is of particular interest as it offers examples of certain typologies of non-state entities that can act as foreign policy makers. In particular, Charountaki argues ←2 | 3→that the Kurdistan Region in Iraq constitutes such a foreign policy (non-state) agent.

While Chapter 1 is grounded in IR theory, Michael Rubin’s contribution in Chapter 2 relies on a deeply historical analysis. Rubin examines the question if—and under what conditions—the United States could ever support Kurdish independence in any of the four Kurdish regions. He offers several insights that point to the possibility of significant change in the near future. Turkey’s questionable behavior as a NATO ally and the uncertain future of Iran, Iraq, and Syria provide some reason for Kurdish optimism in his view: “Unlike in decades past, it is conceivable that sooner rather than later, the Kurds may find official U.S. support for their nationalist aspirations.” Rubin also argues that the Iranian regime may be significantly weaker and more vulnerable than generally assumed.

Chapter 3, co-authored by Thomas Jeffrey Miley and Güney Yildiz, focuses on a sociological analysis of the larger Kurdish movement, namely non-state actors and organizations that are inspired by Abdullah Öcalan. This chapter examines the trajectory of U.S. foreign policy toward the Kurds in general, discusses tactical alliances between the U.S. and Syrian Kurdish forces, and then frames the broader discussion related to democratic aspirations among mobilized Kurds in Turkey and Syria. The co-authors suggest that U.S. characterization of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) as a terrorist organization might change to emphasize the urgent need for a return to peace negotiations in Turkey. Miley and Yildiz also propose that “the ‘War on Terror’ is not only counter-productive in terms of promoting purported values such as human rights, democracy and peace; but also based on an extremely misleading and oversimplified paradigm for understanding the world.” They point out how surreal it has been for the Kurdish movement to be classified as a terrorist organization on the Turkish side of the border, yet to be considered a close and trustworthy American ally on the Syrian side of the border.

In the second section, contributors focus specifically on aspects related to “U.S. Foreign Policy and the Kurdistan Region.” Here, various scholars explore the significant regional fallout from the 2017 (advisory) Kurdistan Independence Referendum, the region’s oil dependency, and the unfulfilled expectations related to the Trump administration’s position toward the KRI (Kurdistan Region of Iraq). This section posits that U.S. administrations are loath to destabilize the region and that the U.S. likely will continue to support efforts by Turkey to co-opt the KRG to actively impede radical Kurdish movements in Syria and Turkey. In Chapter 4, Liam Anderson finds that the Iraqi Kurds’ dramatic loss of Kirkuk in October 2017, following their referendum a month earlier, was “a storyline replete with familiar elements, from the machinations of powerful neighboring predators, to the absence of genuine ←3 | 4→allies to aid the Kurds in their hour of need, and the ruinous propensity of Kurdish leaders to engage in factional infighting.” Anderson proposes that the “right” time for the KRI to pursue independence may never come and that U.S. policy toward the Kurds has been consistent in one particular way, namely that the U.S. never actively supported Kurdish independence nor its claims to Kirkuk. In essence, Anderson’s diagnosis is that the interactions between the Iraqi Kurds and the U.S. have been based on a longstanding pattern of self-interest.

Chapter 5 by Bilal A. Wahab focuses on Iraqi Kurdistan’s dependent economy in the context of aid and oil. Wahab argues that Kurdish nationalism has not managed to transition from a “revolutionary enterprise” to constructive efforts of nation building. In his analysis, “the KRG primarily has itself to blame for its utter unpreparedness to deal with some of the consequence” of the poorly managed economic reforms in light of significant oil wealth for a period of time. Wahab argues that the Kurdish leadership appears all too willing to gamble with Kurdistan’s economic future to advance political agendas.

In Chapter 6, Michael M. Gunter, one of this collection’s two co-editors, analyzes the Trump administration’s policy towards the Syrian, Iraqi, and Turkish Kurds on the one hand, and Turkey and Iraq on the other to find attempts to square the circle in favor of both sides. However, given the U.S. failure to support the KRG’s advisory independence referendum in September 2017 and the announcement of a U.S. withdrawal from Syria in December 2018, it seems that Trump decided to explore a familiar U.S. foreign policy approach regarding the Kurds. Gunter pursues a critical foreign policy analysis by identifying how the Trump administration positioned itself vis-à-vis various Kurdish militias and Kurdish movements. Gunter points out that Trump appears significantly “more favorably disposed toward Turkey than his predecessor” and likely will face challenging issues in the coming year, including the issue of the Pentagon’s cooperation with Syrian Kurdish PYD/YPG/YPJ forces and the future of Syria in the aftermath of the war against ISIS. Despite a deterioration of the U.S.–Turkish strategic partnership, Trump and Erdoğan will engage in “ad hoc balance of power coalitions.”

Chapter 7 by David Romano takes a closer look at perceptions in the KRG at the time of Trump’s election to the U.S. presidency. The Iraqi Kurdish leadership, he suggests, incorrectly interpreted Trump’s anti-Iranian rhetoric as a sign of U.S. support for the Kurdish struggle against Iran’s proxies in Iraq. Romano faults the Trump administration’s policy toward the Kurds for its reliance on “autopilot” and critiques its lack of timely engagement with KRG President Massoud Barzani. Instead of responding to Barzani’s pursuit of a Kurdistan Independence Referendum, the U.S. articulated extremely ←4 | 5→late warnings, which signaled that a Kurdish policy had been lacking. In Washington, D.C., the “trump card” came up as worthless for the Kurds.

The third section on “Kurdish Lobbying, Para-Diplomacy and Rojava” analyzes the ways in which Kurdish movements have responded to longstanding patterns of U.S. foreign policy in the region. The contributors in this segment examine Kurdish lobbying efforts in the U.S., discuss Kurdish para-diplomacy activities in a comparative context, and frame the YPG/J’s and PYD’s (Democratic Union Party) efforts within the Syrian context. In this segment, several scholars disagree with each other and pursue a variety of critical analytical approaches to analyze broader power structures and the ways in which they shape particular Kurdish movements and responses to U.S. foreign policy preferences.

In Chapter 8, Vera Eccarius-Kelly, one of the two co-editors of this volume, pursues a comparative analysis of the challenges faced by formal Kurdish lobbying efforts and Kurdish grassroots political activism in the United States. The literature on ethnic lobbies is quite limited, and within it newly emerging ethnic lobbies such as the Kurdistan lobby have been mostly ignored. Eccarius-Kelly argues that both formal lobbying carried out by the KRG and grassroots mobilization pursued by activists, who aim to advance socio-political conditions for Kurds in Turkey and Syria, enjoy very limited opportunities to shape specific foreign policy directions in the U.S. She concludes that it is practically impossible for an ethnic lobby to shift U.S. foreign policy directions without a clear convergence of shared interests between a U.S. administration and an ethnic lobby. In Chapter 9, Haluk Baran Bingöl also relies on a comparative analysis to place Kurdish para-diplomatic activities into a larger analytical discussion. He grounds his analysis within the body of literature related to para-diplomacy studies but also contrasts the Quebecois experience to the Kurdish quadri-regional case. Bingöl advances the notion that scholars need to move beyond the standard neoliberal and neofunctionalist approaches to consider the growing literature in para-diplomacy to adequately analyze the significant progress Kurdish regions have made as sub-state or sub-group actors.

Chapter 10 by Eva Savelsberg engages with the extremely hostile encounters between the Turkish state and the Syrian Democratic Forces (including the YPG/YPJ). She contends that it is “quite unlikely that Turkey will stop demanding that the Pentagon cut off U.S. support for the SDF” and that the “outcome of the Afrin operation hardly satisfies Ankara.” At the same time Savelsberg argues that the PYD (Democratic Union Party) in Syria, an affiliate of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), is one of the few winners of the Syrian civil war. She harshly criticizes the PYD for its unwillingness to engage ←7 | 8→←6 | 7→←5 | 6→←8 | 9→in power sharing arrangements as well as for serious violations related to freedom of speech and human rights.

Finally, Huseyin Rasit in Chapter 11 offers a deeply critical and theoretical intervention by analyzing U.S.-Rojava relations. Rasit argues that interactions between the United States and Rojava cannot be simply framed as those between an “established nation-state pursuing its national interests” and a “non-state actor seeking recognition.” Instead, he proposes to explore the relationship between Kurds in Syria and the U.S. through the prism of arch-imperialism and counterrevolution. Rasit questions common practices of reproducing the imperial gaze in the Middle East, yet at the same time he challenges simplistic and de-contextualized leftist critiques of Rojava as a project of revolutionary liberation. In essence, he posits that it is highly likely that Kurds will continue to “keep a central place in foreign policy discussions in the foreseeable future,” suggesting that it would behoove scholars from all academic disciplines to reflect on their own positionality.3

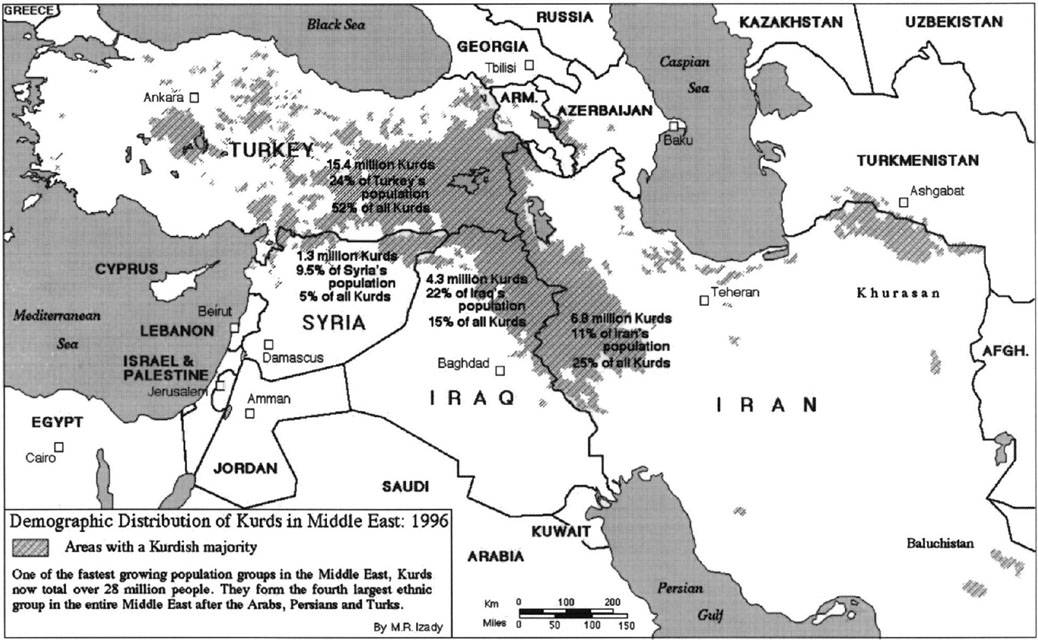

Figure 1. Demographic distribution of Kurds in Middle East, 1996.

Photo from The Historical Dictionary of the Kurds, 3e by Michael M. Gunter.

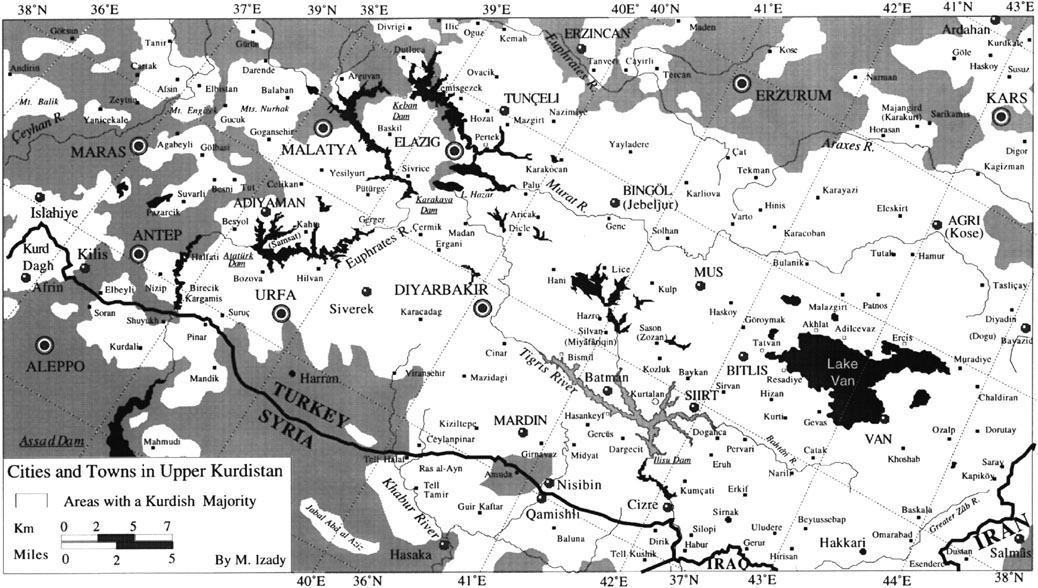

Figure 2. Cities and towns in Upper Kurdistan.

Photo from The Historical Dictionary of the Kurds, 3e by Michael M. Gunter.

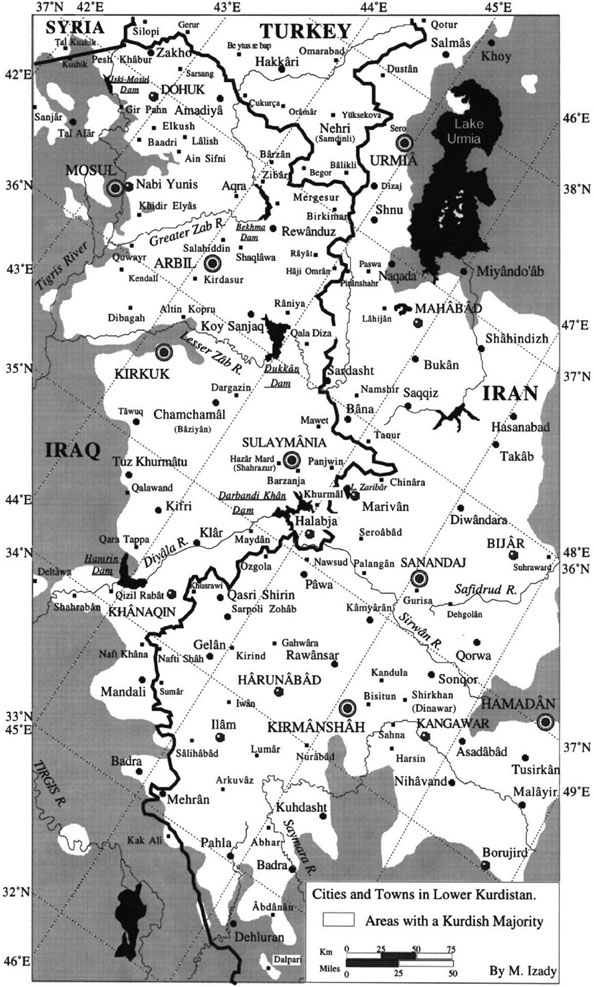

Figure 3. Cities and towns in Lower Kurdistan.

Photo from The Historical Dictionary of the Kurds, 3e by Michael M. Gunter.

Notes

1 Michael M. Gunter, “US Middle East Policy and the Kurds,” Orient 58, no. 2 (2017), 43–51.

2 Cited in “The CIA Report the President Doesn’t Want You to Read,” [The Pike Committee Report] The Village Voice, February 16, 1976, pp. 70–92. The part dealing with the Kurds is entitled “Case 2: Arms Support,” and appears on pp. 85 and 87–88.

3 Vera Eccarius-Kelly, “Critical Ethnography: Emancipatory Knowledge and Alternative Dialogues,” in Methodological Approaches in Kurdish Studies, ed. Bahar Baser, et al. (New York: Lexington Books, 2019), 3–20.←9 | 10→

Details

- Pages

- X, 252

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433168024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433168031

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433168048

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433168055

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15504

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (February)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. X, 252 pp., 3 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG