Advertising the Black Stuff in Ireland 1959-1999

Increments of change

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

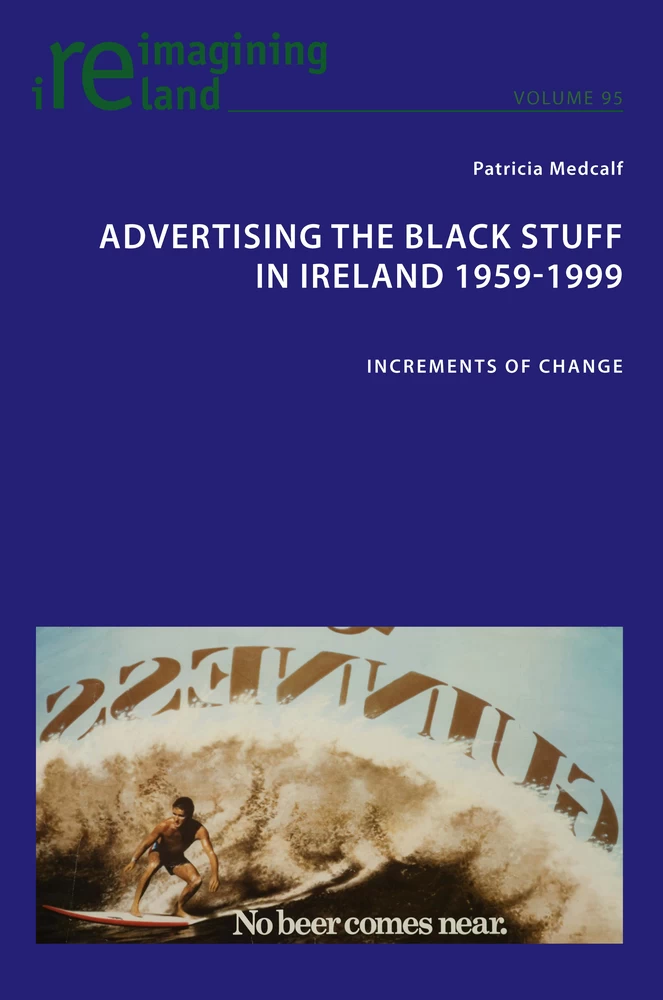

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Citability of the eBook

- Contents

- Figures

- Foreword by Patrick Guinness

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The question at the heart of this book

- Exploring the Guinness Archive

- Chapter 1 1959–1969: New beginnings

- Guinness: A key player in Ireland’s economic success

- Guinness and early TV advertising

- Travel and tourism

- Guardians of Irish culture

- Breaking down barriers: Portraying women in the pub

- Conclusion

- Chapter 2 1970–1979: Emerging voices

- Evolving economic landscape and changing alcohol consumption patterns

- The 1970s: A seminal decade in redefining women’s role in Irish society

- Timelessness, continuity and heritage

- A sense of identity

- Conclusion

- Chapter 3 1980–1989: Economic hardship

- A tap that could not be turned off

- Donning the rose-tinted glasses

- Living on an island

- The boundaries come crashing down

- Dancing to a different tune

- Everything should be the same … or should it?

- Conclusion

- Chapter 4 1990–1999: A period of unprecedented change

- The Celtic Tiger: A ‘tail’ of two halves

- The Celtic Tiger and the marketing communications sector

- 1990–1994: Easy as she goes for Guinness’s advertising

- A hangover from the 1980s

- There’s no time like Guinness time

- New names, new beginnings

- Let’s talk about sex

- What is the point of the Big Pint?

- Live life to the power of Guinness

- Conclusion

- Concluding thoughts

- Bibliography

- Index

Figure 1: The first Irish ad from Guinness

Figure 2: 200 years of Guinness – What a lovely long drink (agriculture)

Figure 3: Guinness – that’s a drink and a half (1)

Figure 4: Guinness – that’s a drink and a half (2)

Figure 5: Ireland is famous for

Figure 6: Daher kommt also die Gute!

Figure 7: The beginner’s guide to goodness

Figure 8: Get close to your Guinness

Figure 14: Cupboard loveliness

Figure 15: Bíonn tú sona sásta le Guinness

Figure 16: There’s far better value in a Guinness

Figure 17: Take the smooth with the rough

Figure 18: Have a Guinness tonight – just between friends

Figure 20: Carrick-a-Rede Bridge

Figure 22: The long and the short of it

Figure 23: This man can level whole counties

Figure 24: Disraeli says: I supped at the Carlton

Figure 25: Guinness – where in the world would you be without it?

Selling beer is different from selling a beer, as it depends upon consistent brewing. Until the late 1800s the family sold Guinness only within 10 miles of Dublin, requiring consistent agents to take it far beyond the city. The business grew but its centre remained at St James’s Gate, a vast but intricate clock serviced by several thousand Dubliners.

My first memories of the brewery in the early 1960s as a little boy were of huge brick walls, pipes, tunnels, steam and smoke, smiling faces, grubby overalls, a small train, barrels everywhere, a place with no centre. My genial tweed-suited grandfather Bryan was somehow involved in managing it all, and everyone said that it was special to Dublin. Gilroyʼs zany animal posters selling the stout also made sense because I knew that Grandad was a sponsor of Dublin Zoo. I didnʼt know that Bryan, as Lord Moyne, had argued against television advertising in the House of Lords in 1953–4, seeing it as an expensive and Orwellian method. Thankfully he was voted down, and Guinness ads were the second to be broadcast in Britain. He and the board also sponsored the Book of Records from 1955 as another marketing tool that has proved to be a huge success in its own right.

Aged 10, in 1966, I had my first full tour, which took three hours, and emerged onto the tall white grainstore roof from which the entire capital could be seen. Also in 1966 came the 1916 commemorations, so along with the Beatles and Percy French, I learned songs from a darker past. Other Dubliners had not prospered as we had, but still expected a better future. My parents’ friend Máire Comerford, a doyenne of 1916, pronounced that I was ready to join the Fianna scouts. To me, and perhaps my family, the brewery running its own bank, fire service, water, ships and trains, theatre, pool, pensions, sports fields, security, post office and health centres, was prospering and semi-independent long before 1916. Did I mention the zoo?

As we had no television at home in Kildare, childhood was face-to-face, local and unfiltered. Thankfully the wooden TV advertising of the 1960s passed me by. By the mid-1970s I was a student in Dublin, and beer and ←xi | xii→colour television became new aspects in my life. Everyone felt that Guinness was a good product, if not as edgy as lagers like Colt 45. Guinness TV advertising was indisputably funnier and more original than the rest. Each campaign resembled an art film or mini-series, using a soft-sell technique. This is the world that Patricia Medcalf captures so thoroughly, charting the evolution from the staid 1950s and working up to that magic moment when the brand name disappeared. The colours, sounds and mise-en-scène all whispered: ‘this must be the new Guinness ad’. The brand became implicit. The product vanished, as it was being sold in the subconscious. The brewery shrank from 3-D to a trickle of electrons between our ears. Co-founding the brand manager Diageo was the obvious next step. This magic was easier when there was one screen per household and only two to six channels, watched by millions of families. Recognising the latest Guinness ad before it ended became a family parlour game. Will this marketing focus ever be possible again? It was much easier than the internet, but thanks to the web those electrons have trickled backwards, and now millions want to see, smell and touch the 3-D brewery.

Dr Medcalf also skilfully weaves emerging Irish social themes around these evolving advertisements. Ireland had its real revolution in about 1990, and her timeframe of 1959–99 encompasses that moment. If the State often looked to the past, the people wanted a future, and Ireland suddenly outgrew herself, much as the brewery had outgrown Dublin. Yet in newer campaigns, traditional music and stout can still dreamily complement and adorn our elemental island. Desire, beauty, heritage; what more do we need?

The genesis of this book stems from my PhD, which was skilfully guided by my supervisor, Dr Eamon Maher. He encouraged me to embark on that journey and has been a source of encouragement ever since. Thanks also to Dr Brian Murphy for his frequent words of encouragement and for his feedback on my work. I am also very appreciative of the wider AFIS community in Ireland and France. Sincere thanks to Dr Eugene O’Brien and Dr Neil O’Boyle for recognising the book’s potential and for offering suggestions that would enhance it.

I am extremely grateful to Eibhlín Colgan and Fergus Brady at the Guinness Archive. They have been most generous with their time, expertise and resources. Without them, this book would not have been possible.

I would like to extend my thanks to Tony Mason, Senior Commissioning Editor at Peter Lang, who was prepared to give me the opportunity to publish my work. Special thanks to Patrick Guinness for agreeing to write such an evocative foreword.

I really appreciated meeting up with Ian Young, former chairman of BBDO (Dublin), who shared his own views on Guinness advertising with me. His insights were invaluable and reassured me that my analysis was on the right track.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 228

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789973457

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789973464

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789973471

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789973488

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15509

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (February)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2020. XIV, 228 pp., 25 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG