Critical Consciousness, Social Justice and Resistance

The Experiences of Young Children Living on the Streets in India

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Permissions

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: We Are the Stories We Tell

- 1 Critical Education for Critical Times

- Education and Ideology

- Education and Critical Consciousness

- Dangerous Education for Dangerous Times: A Case for Critical Consciousness and Social Justice Education in the Early Years

- Who Are the Children Living on the Street?

- Why Research with Young Children Living on the Street?

- Mumbai, India: The Research Context

- India

- Mumbai

- Central Research Questions

- Transparency: The Researcher as a Human Instrument

- My Story

- The Importance of a Book on Critical Consciousness and Social Justice in the Early Years

- Book Structure

- 2 Theory for Knowing and Changing the System

- Critical Pedagogy: What Is It? Where Did It Come from?

- Critical Pedagogy and the Purpose of Education

- Knowing the System

- Characteristics of Critical Pedagogy

- Education Is Political

- Ideology

- Hegemony

- Historicity of Knowledge

- Regimes of Truth

- Micropractices of Power

- Developmentally Appropriate Practices

- Political Economy

- Culture, Race and Gender

- Changing the System

- Resistance and Counter-hegemonic Discourses

- Resistance Theory

- Critiques of Resistance Theory

- Ideological Critique

- Critical Consciousness

- Praxis

- Dialogue and Problem-Posing Education

- Repositioning

- Critiques of Critical Pedagogy

- Justifying the Use of Critical Pedagogy to the Research Reported on in This Book

- Critical Pedagogy and the Indian Context

- Conclusion

- 3 Critical Consciousness and Social Justice in Early Childhood

- Literature Review Search Methods and Inclusion Criteria

- Understanding Critical Consciousness

- Understanding Social Justice

- Critical Social Justice

- Interconnected Understandings: Social Justice and Critical Consciousness

- Education for Critical Consciousness

- Community-Based Approaches to Developing Critical Consciousness

- Adult Education for Critical Consciousness

- Research with Pre-service Teachers

- Research with Teachers

- Critical Consciousness for Education with Children

- Early Childhood Contexts

- Gaps in the Literature and the Current Study

- Conclusion

- 4 Researching with Young Children Living on the Streets

- The Mosaic Approach

- Pieces of the Mosaic

- Critiques of the Mosaic Approach

- Using the Mosaic Approach in This Study

- Ethical Considerations

- Informed Consent

- Power Relations and Imbalances

- Sensitive Information, Confidentiality and Privacy

- Research Context: The Centre and the Streets

- Participant Selection and Recruitment

- Participants

- Data Collection

- Observations and Field Notes

- Dialogue and Informal Conversation

- Drawing and Storytelling

- Child-Led Photography and Tours

- Data Analysis

- Rigour and Credibility

- Triangulation

- Reflexivity

- Voice and Collaboration

- Prolonged Engagement in the Field

- Limitations

- Conclusion

- 5 The Indian Context

- Why Is a Chapter on the Indian Context Necessary?

- Framing the Historical Analysis

- Colonisation

- Ideology

- Civil and Criminal Justice System

- Slavery

- Independence and the Partition

- Modern Republic of India

- Religion

- Hinduism and the Caste System

- Christianity in India

- Muslims in India

- Religious Riots and Terrorism

- Political and Socio-economic Structures

- Symbolic Violence and the Treatment of Women

- Female Infanticide

- Child Marriage

- Educational Inequality and Exclusion on the Basis of Gender

- Education Systems in India

- Early Childhood Provisions

- Primary School Systems

- Mumbai

- Children Living on the Streets in Mumbai

- Prevalence

- Causes

- Education

- Economic Activity

- Challenges

- Support Mechanisms

- Re-meeting the Complex Interplay of History, Economics, Politics and Society: Educational Contexts, Children Living on the Streets and This Research

- Conclusion

- 6 The Stories We Tell

- Using Resistance Theory

- Profile of Participants

- Akbar,2 Male, 7.5 Years Old

- Arav, Male, 4.5 Years Old

- Bhijali, Female, 3.5 Years Old

- Birbal, Male, 7 Years Old

- Krish, Male, 4.5 Years Old

- Payal, Female, 5 Years Old

- Rani, Female, 7 Years Old

- Rathore, Male, 8 Years Old

- Sonakshi, Female, 4 Years Old

- Tara, Female, 4.5 Years Old

- Children’s Lived Experiences and Perspectives

- Conformist Resistance

- Learning English

- Belief in the System of Education

- Caretaking

- Self-defeating Resistance

- Apathy and Self-soothing

- Self-deprecating and Destructive Behaviours

- Systematic Understanding and Critique

- Obedience and Underlife

- Transformative Resistance

- Aspirations and Plans to ‘Be Someone’

- Creative Problem Solving

- Ensuring Fairness

- Speaking Out

- Helping and Teaching Others Social Justice

- Dignity Work

- Conclusion

- 7 Resistance for Social Justice and Critical Consciousness

- Language Hierarchies, Neoliberal and Developmental Discourses: Divide and Rule

- Language Hierarchies and Neoliberal Discourses

- Developmental Discourses and Micropractices of Power

- Resistant Behaviour as Communication

- Resistance as a Communication of Self-defence and Agency

- Resistance as a Communication of the Desire for Social Justice and Listening

- Underlife Resistance, Dignity and the Pedagogy of Indignation

- Policy Implications

- Research Implications

- Practice Implications

- Limitations and Further Research Suggestions

- Conclusion

- 8 Summary: If Gandhi was a Child in Your Classroom

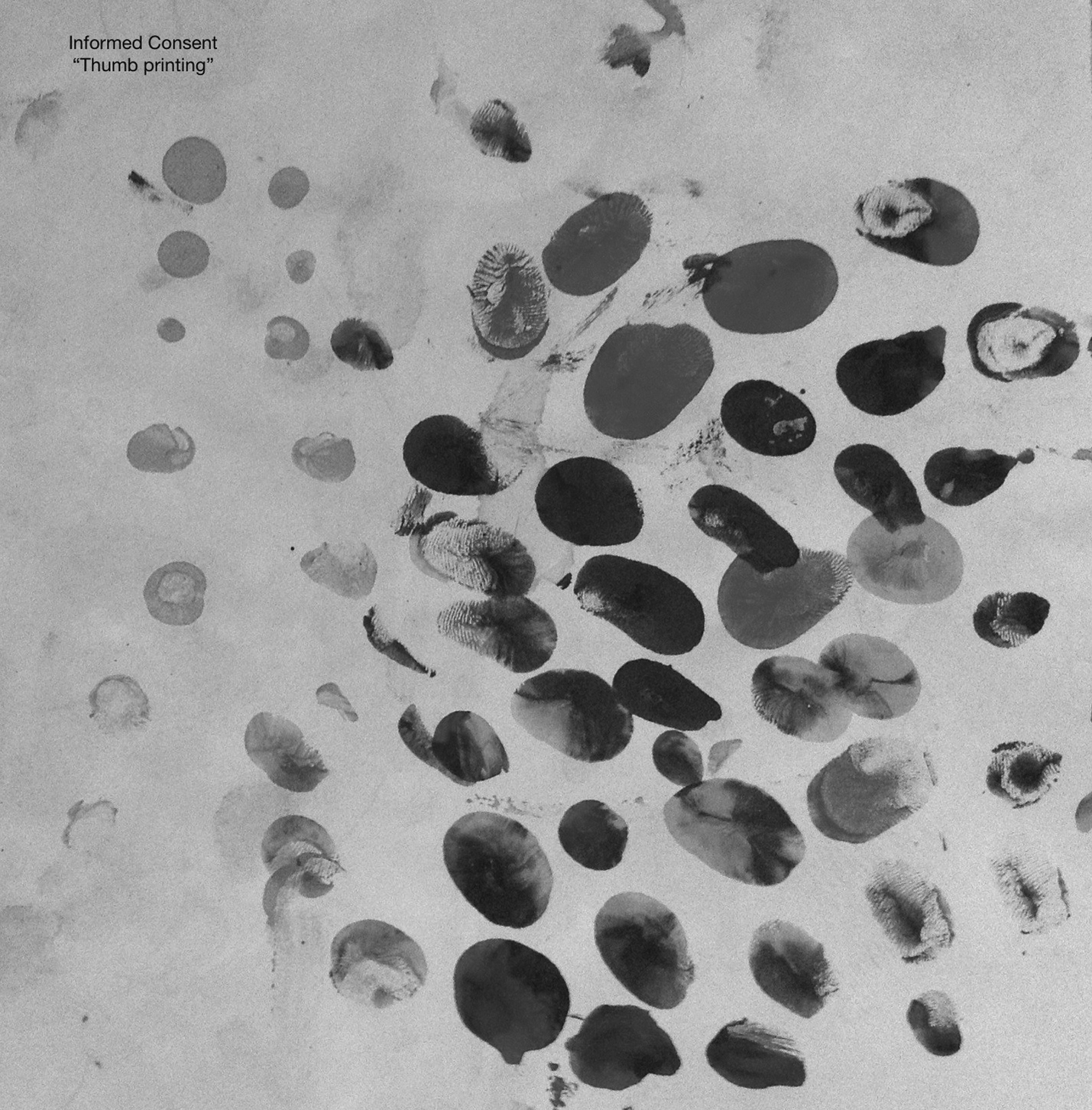

Figure P.1: Informed consent: Thumb printing

Figure 6.1: Arav draws the council burning homes

Figure 6.2: Birbal’s (Male, 7) Story called “Police, Inspector, Baton”

I am immensely grateful to all those who made this work possible. My foremost thanks to Professor Jacqueline Hayden, Dr Kathy Cologon and Dr Fay Hadley. Thank you, Jacqueline for your unending generosity, your lively humour, and for being an indelible visionary who truly lives by the vivacity of life beyond borders. Thank you, Kathy for reading (and re-reading, and re-reading!) this work and for always radiating warmth, hand in hand with critical brilliance, and for being a spirited and fiery revolutionary (a smiling face with a backbone of steel!)—always lighting the dusty shadows of doubt and deflation with hope and resistance! Thank you, Fay, for starting it all, and for always finding a way to guide me clearly, thoughtfully and calmly through all the research storms.

My many sincere thanks to all the children, families and educators who participated in this study and who shared the ‘fullness’ of their lives so openly and artfully with me—this work would not have been possible without your voices, teachings, and of course, your critical consciousness, resistance and motivation for social justice!

My deepest thanks to Professor McLaren and Professor Peters for the opportunity to turn a dusty dissertation into a book—thank you for your encouragement, your guidance and your thoughtful and rich feedback. My sincerest thanks also to Patty Mulrane and Monica Baum at Peter Lang for your (ongoing!) ←xv | xvi→patience—I am indebted to you for your kindness and the wonderfully gentle way in which you helped move this work along! Thank you also to Professor Fazal Rizvi for your wise direction and thoughtful feedback.

A big thank you to my family and friends—especially my parents, Zarin and Kobad, for their unconditional love and encouragement, and their never-ending belief in the power of education. Many thanks also to Sehroo M. Tata, Armaity Mevawalla, Vijanti Vaikar and Neeta Borkar—for their generous care and attention throughout my time in India. Thank you also to Natasha, Christoph, Hannah and Benjamin for being such wonderful sources of pure and unadulterated happiness. My thanks also to Joel David, Taronish and Xavian for being an infinite and adoring source of humour, tea and comfort, and to Sanobia and Jane—for always being so genuine, for always truly listening, and for always standing by my side.

Children’s words and artworks (collected as part of a doctoral dissertation) are used in this book. Permissions for this study were gained with young children by asking children to consent to a verbal script and then to make a mark using a thumb print on a shared paper—this arose from a conversation with children about consent, and was done since children could use the thumb print giving to indicate that they had ‘voted’ to participate in the study—(voters in India are marked with ink on one finger to show they have voted).

←xvii | xviii→←xviii | xix→Introduction: We Are the Stories We Tell

Why is it that the very first version of a story that is heard—is the most powerful one encountered? That even before you can start to ask yourself, what the full story is, you inevitably start to make judgements—to feel and think and want and divide in your mind; what is right, what is wrong, who you like, who you don’t, what you’ll believe and what you won’t. That first version becomes the basis from which you think of and hear all the Other1 versions of a story through. It is the looking glass from which you see the world of the story—and by that very virtue, certain ‘ways of doing’, ‘ways of being’ and ‘ways of thinking’ imbibed in that one version—come to be sub-consciously taken as the ways of doing, being and thinking. Over time, as the first version becomes the most told (and heard), it so happens that its ways seem to seep internally to an understanding of what is natural—and it comes to tell us what we know (or think we know) about the whole story, and of everything and everyone in it.

Even if these ways of doing, being and thinking, are rigid, irrelevant, de-contextualised, unfair, exclusionary, and oppressive—we begin to pass them on, through the simple act of telling and re-telling, from one person to the next, without so much as realising the power hidden in the folds of this unquestioning rote. If a different version of the same story is told, it is judged by the pre-conceived understandings of the first—either to fit with or to be set aside, because it makes ←1 | 2→uncertain the credibility of what has now come to be taken-for-granted. As time passes, because the re-telling of this one version has become the re-telling of the whole story, the question of why comes to be lost against itself—and the answer comes to be: because that is the way it is—as though the act of telling and re-telling has absolved our thoughts of thought-filled words and put our whole consciousness and mindfulness to sleep in its place.

Recognising the power of a version as a version that is lived and living, by thinking and listening, questioning and creating, in order to un-know and re-know the known is the ‘waking up’—or in other words—the critical consciousness, that affords us opportunities to question the monopolies that prevent us from seeing the world (and acting in it) anew. Critical consciousness helps us question (and counter) which versions are heard, whilst bringing into focus the role of those telling us stories, as well as the role of those being told. Engaging in this process of critical consciousness means that listening becomes reciprocal as participation becomes full. The story’s truths become subject to socio-historical critique, as understandings become angled. Previously unknown and untold versions slowly emanate—and small resistant cracks appear in the oppressive and all-encompassing dome of dominant discourses, offering a ray of critical sunlit hope. As this happens, social justice becomes the process by which the Other use their versions and voices to cut through the restrictions that punish them for refusing to conform to the status quo’s neat boxes and lines. From this defiant spirit bloom counter-stories—the protagonists of which advise: We are not defined by your theories, your systems, your sanctions, your gaze, your lens, your eyes. We are not your stories. We are the stories we tell.

Working in solidarity with oppressed groups against the diktats of socio-educational bureaucracies, social justice educators surmise; that democracy will breathe if, and when, conformity is no longer the myth to which equality strives. If, and when, education systems stop viewing Others as blank slates, waiting to be turned into the same. If, and when, equity, freedom, inclusion, justice and fairness are educational as well as social, political and economic goals. Equity. Inclusion. Freedom. Justice. Aren’t these what education is supposed to be for? Is this not why education is so important? Important enough to be invaluable? Important enough to be dangerous? Important enough that it is a kind of irrevocable power that changes who you are and leaves you with an incalculable view of the world and of yourself; that takes you to a place of mind that you could never before have fathomed, and that you can now never return from again, no matter how hard you try.

Critical educators write lovingly of the possibilities. Of the ways in which education can and should be premised in creating political and ethical entry ←2 | 3→points—through which we can actively struggle for social justice, that is, transformation against all forms of discrimination, unfairness, inequity and oppression. And yet! Critical educators fight the prostitution of education systems to neoliberalism, cultural imperialism, and ‘de-politicised’ technical rationalities that seek to standardise and normalise children, de-skill the teaching profession, and in turn, ‘educate’ the citizenry into internalising and naturalising injustices and inequities that oppress and dehumanise. How is it possible to teach for social justice, in a ‘democracy’ that anesthetizes learning into a process of obedience, silence and uncritical acceptance?

With this in mind it, the purpose of this book is to invite critical educators to reflect on the question of how social justice education can work within unequal and unfair systems to capture the complexity of critical consciousness as it unfolds in praxis, whilst simultaneously opening avenues for the transformation of immediate and broader forms of political, economic, social, historical and cultural oppression. It is not possible to easily answer such a question. And yet! What is possible is to find (sometimes unexpectedly) educators that work with such questions, and learners that do not obey, that do not silence, that do not accept—the injustices that society has afforded them. Grappling with this question, the purpose of this book is to share the counter-stories of 10 young learners who engaged in resistance to struggle for dignity, recognition, participation, inclusion and equity whilst living on the streets of Mumbai, India. These children (aged 3–8), in the early years of their life, battled against oppression, injustice, stigma and discrimination in their communities as well as in the educational settings they attended. Importantly, the research project that this book reports on did not start out as a search for these resisters or game changers, rebels or revolutionaries. It began by seeking to explore the ways in which young children react to (or absorb) notions of power, privilege and/or oppression. The study was originally developed to investigate how this oppression might be interrupted, and how a notion of social justice is, or can be, formed. It was through research, and my own (still ongoing) process of developing critical consciousness that I came to re-see and re-listen to those children that voiced their own versions and interrupt universal or dogmatic truths.

This book draws on snippets of qualitative evidence from children’s lived experiences, stories and perspectives in order to show how children (when motivated by social justice and armed with critical consciousness) can challenge, play with, laugh at, and resist oppressive situations in order to change their worlds and their lives for the better. Using a critical pedagogy lens, this book explores the ways in which these young children engaged with the praxis of ←3 | 4→critical consciousness to participate in (and create spaces for) resistance and possibility (Giroux, 2001; McLaren, 2015). The book focuses specifically on the early childhood years as this time of life has been identified as laying the foundation for enculturation and/or transformation—that is, where taken-for-granted ways of being, doing, and thinking are learnt, or can be learnt to be challenged. The findings from this study show both how children’s understandings and behaviours assimilate to dominant discourses, as well as how children participate in every day, hidden and underlife forms of resistance. In unpacking these elements, the book invites readers to consider what possibilities might emerge from listening to, and developing, children’s critical consciousness, motivation for social justice and resistance.

Note

1 1. The term Other is used throughout this book to signify binaries pertaining to what is considered (i.e., socially constructed) to be ‘normal’ and ‘other’. Mac Naughton (2005) identifies that ‘othering’ inadvertently discriminates, or renders inferior, that which is not dominant in discourse, ideology or practice.

References

Giroux, H. A. (2001). Theory and resistance in education: Towards a pedagogy for the opposition. London, England: Bergin & Garvey.

Mac Naughton, G. (2005). Doing Foucault in early childhood studies: Applying poststuctural ideas. London, England: Routledge.

McLaren, P. (2015). Pedagogy of insurrection: From resurrection to revolution. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

1

Critical Education for Critical Times

We live in a world in crisis—a world governed by politics of domination, one in which the belief in a notion of superior and inferior, and its concomitant ideology—that the superior should rule over the inferior—effects the lives of all people everywhere, whether poor or privileged, literate or illiterate. Systematic dehumanisation, worldwide famine, ecological devastation, industrial contamination, and the possibility of nuclear destruction are realities which remind us daily that we are in crisis. (hooks, 1989, p. 19)

In 1989, bell hooks identified a world in crisis. Thirty years later, analysts suggest that humanity continues to find itself in increasingly dangerous and uncertain times. Critics write of the corrosive effects of prevailing economic, political and social zeitgeists, highlighting the ways in which exploitation, cultural imperialism, and inequality have come to be justified as part of ‘democratic’ or ‘meritocratic’ systems (Darder, 2002; Kincheloe, 2008; McLaren, 2005; Paraskeva, 2019). Within such frames of reality, Fielding and Moss (2012) urge educators, policy makers, researchers, and the public to critically consider the purpose of education, asking; “what is education for?” (p. 28), and, what is the role of education in preparing students to meet the dangers and uncertainties that are, or will be, faced by humankind? In response, Biesta (2015) explores educational intentions resting in three overlapping aims, the first; to acquire knowledge, skills and attitudes, the second; to socialise children into cultural, political, social and economic ways of ←5 | 6→doing, being and thinking, and the third, to develop subjectivities, personhood or agency.

Extending on these aims, critical theorists argue that the fundamental purpose of education is emancipation from oppressive social relations and the betterment of living (human and non-human) ecologies. Thus, rather than processes of socialisation, which orient learners to socio-historically devised ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ ways of thinking, being and doing, these thinkers postulate that what is needed is a problem-posing education—one which struggles for critical consciousness and social justice (Shor, 2012). As Freire (1970, 1998) explains, a problem-posing approach to education works to de-familiarise, question and critique ideologies, taken-for-granted ‘truths’ and ways of thinking, being and doing, thereby inventing, re-inventing, and socially co-constructing knowledge together with learners and teachers, through dialogue. Ideology critique or challenging the ‘natural’ process of socialising learners into the existing status quo can be seen as fundamental to this endeavour since education cannot be free from ideologies and values, and is therefore always political (Freire, 1970)(this is discussed further in Chapter 2).

Details

- Pages

- XX, 296

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433168406

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433168413

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433168420

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433168444

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433168437

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16302

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (April)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XX, 296 pp., 3 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG