Bitches Unleashed

Performance and Embodied Politics in Favela Funk

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Advance praise

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introducing Bitches Unleashed

- Chapter One: Femininities, Agency, and White Feminist Failures

- Chapter Two: “I Don’t Depend on Men for Shit!”: Favela Funk as Industry and Funkeiras’ Autonomy

- Chapter Three: Femininities on Display: Transgression and the Body in Performance

- Chapter Four: Negotiated Femininities: Relationships with Men and Other Funkeiras

- Chapter Five: Anti-Blackness and Racial Consciousness among Funkeiras

- Chapter Six: “Sit Down and Observe Your Own Destruction, Macho!”: Travesti Performances in Favela Funk

- Beyond Survival: Funkeiras, Embodied Politics, and the Future of Feminism

- Index

- Series index

Figures

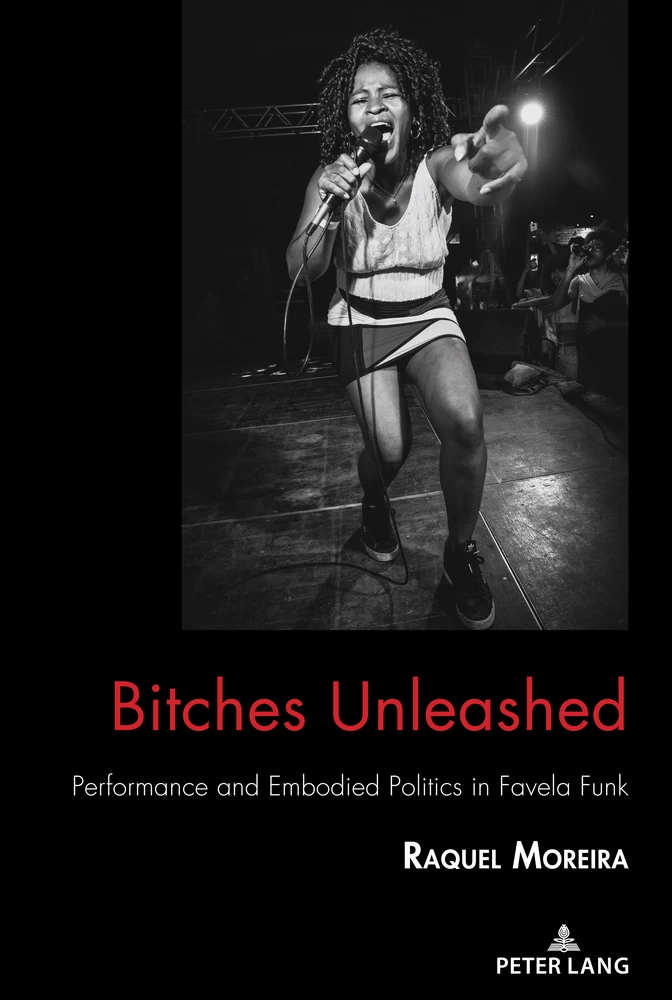

Cover: Deize Tigrona live performance

Credit: Vincent Rosenblatt

Credit: Fernando Schlaepfer/I Hate Flash

Credit: Brenda Barbosa

Credit: Marina Costa

Figure 4: Linn da Quebrada posing

Credit: Gabriel Renne

Acknowledgements

I have been meaning to write this book for at least the past five years. Countless people have helped me find the courage and time to finally do it. The process of finding courage and time to do it has been influenced by countless people. I am grateful for their support during this demanding and all-consuming process.

First and foremost, I would like to thank my partner, Isaac Pressnell, who has been my emotional pillar during this taxing time. Thank you, my love, for caring for our daughter, Isadora, our dog, Gatolinos, our house, and my emotional needs—all while dealing with a global pandemic, a chronic illness diagnosis, and the death of my father. Thank you, Isaac, for giving me space to write this book during an impossible time in our lives. We both know I would still be procrastinating if not for your constant reminders that this was actually the right time to do it.

I want to thank Bernadette Marie Calafell for her intellectual generosity and mentorship. It has been an honor to learn from and with her. I remember the first time she told me to submit a book proposal. It was in Las Vegas, during the 2015 NCA, as we walked into an elevator. It only took me four years to follow through. Thank you, Bernadette, for ←xi | xii→encouraging me to write this book. Her request for a proposal made me feel accountable to finishing this work.

To Deize Tigrona, Dandara, MC Carol (and Ana Paula!), MC Xuxú, Linn da Quebrada (and Izabela!), MC Kátia and LD, MC Pink, and the Abysolutas: this work exists because of them. I am eternally grateful for all that I have learned during our time together. Meeting you has changed my life.

I am thankful for my Brazilian family, Carla Moreira, Luiz Carlos Moreira, Maria Martha Bruno and Carolina Damico for their support during and after my 2013 fieldwork. Every single one of you has lent me a car to go meet with an artist or attend a performance. Mom, thank you for coming to a not-so-safe party with me—and for not freaking out about it. Grandpa, thank you for your financial support during that summer. Even though you are not a big funk carioca fan, you are still a champion for social justice.

To my Cidade de Deus friends, Don and Mingau, thank you so much for spending time with and for introducing me to so many funkeiras. I will never forget the afternoon we spent at MC Mãe’s (descanse em paz) rooftop in 2012—that was the first time I heard about MC Carol. Many thanks to Felícia Cristina, who took me to a baile in São Gonçalo and put me in touch with several artists.

Many thanks to my copy-editor, Kristen Foht, for her curiosity, competence, and thoroughness. I could not have done this without her help. I am thankful, too, for my Peter Lang editors, Erika Hendrix and Ashita Shah, who were patient and helpful throughout this process.

I am grateful for my friend, Jen Abraham, who joined our family pod during the Covid-19 pandemic to help us care for our baby. I did not think I would be able to have whole-day writing retreats! I would also like to thank my fierce academic friends for their support and encouragement over the years: Dr. Fatima Zahrae Chrifi Alaoui, Dr. Leslie Rossman, Dr. Shadee Abdi, Dr. Pavithra Prasad, Dr. Catherine Clifford, and Dr. Kristin Seemuth-Whaley. Your badassery inspires me. I am also grateful for my dear friend Paula Martin, who was my emotional rock during my DU years.←xii | xiii→

I would like to acknowledge Dr. Adriana Carvalho Lopes’s indispensable favela funk book, Funk-se Quem Quiser. Her work has had a tremendous impact on this project. Thanks also to Dr. Adriana Facina, Dr. Carlos Palombini, Dr. Pâmella Passos, and Dr. Pablo Laignier for their contributions to favela funk research. A special thanks to Dr. Mariana Gomes for sharing her passion for funkeiras (and frustrations with feminism) with me.

I would like to thank my University of Denver’s Department of Communication Studies professors for their intellectual support, especially my dissertation committee members, Dr. Richie Hao, Dr. Darrin Hicks, and Dr. Luis León (descansa en paz).

I am very grateful for the scholars whose work have impacted this book deeply: the late Dr. José Esteban Muñoz, Dr. D. Soyini Madison, Dr. Mariza Corrêa, Dr. Sueli Carneiro, Dr. Jaqueline Gomes de Jesus, Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, Dr. Chandra Mohanty, Viviane Vergueiro, Dr. Brittney Cooper, Dr. Aisha Durham, Dr. Gust Yep, Dr. Karma Chávez, Dr. Shinsuke Eguchi, Dr. Rhea Ashley Hoskin, and countless others.

Many thanks to my Graceland University friends, who have amazed me during our many hallway conversations: Dr. Tim Robbins, Dr. Dan Platt, Jessie Sherman, Karen Gergely, Dr. Jonathan Montalvo, Leslie and Nate Robinson, Dr. Brittany Lash, and Dr. Steve Glazer. Special thanks to Dr. Brian White and Dr. Jill Rhae for helping me fight for and receive institutional support for this book.

I am also thankful for my Latina/o Communication Studies friends/colleagues, whose work and dedication to our field always amazes me: Dr. Michael Lechuga, Dr. Robert Gutierrez-Perez, Dr. Leandra Hernández, Dr. Sarah De Los Santos-Upton, Dr. José Ángel Maldonado, Oscar Alfonso Mejía, Dr. Sara Baugh, Dr. Sergio Juarez, and many others.

I would like to thank my friend, Dr. Pedro Curi, for sending me a Valesca Popozuda video back in 2009 that triggered many ideas for this work. I am also grateful for Dr. Marildo Nercolini and Dr. Alexandre Werneck, for having one of the first talks about the funkeiras with me in 2009 as well.←xiii | xiv→

Many thanks to Vincent Rosenblatt for allowing me to have his beautiful work illustrating this book cover.

To everyone who has supported me through this journey, thank you with all my heart. It really does take a village.

Introducing Bitches Unleashed

In the music video for Linn da Quebrada’s “Coytada” (“Poor Girl”),1 she chops up dildos of different shades on a cutting board. The video mimics a cooking show in which Linn and fellow Black travestis Jup do Bairro and Slim Soledad sensually and frantically play with baking ingredients: swallowing and spitting back out eggs, blowing flour on each other, pouring milk in their own mouths, and using rolling pins on dildos. The lyrics suggest that Linn would rather have sex with the devil than with someone who only likes “gym rats” and “bulls” (muscular men) because, according to her, “I’m very effeminate.”2 Linn da Quebrada illustrates well why I have been obstinate in my interest in favela funk as a research topic for the last 10 years. When I first started to notice the movement for the purpose of studying it, a performance like hers—even her popularity—would have been unthinkable. This book is a result of my journey after a decade of dedication to, first, women in favela funk and, now, to all who perform femininities within the movement. They are known as the funkeiras.

Rio de Janeiro’s favela funk is a musical genre and cultural movement developed by poor folks of color in the 1980s. The characteristic ←1 | 2→beats, lyrics, dance moves, and clothing suggest a “social practice that is historically situated:”3 favela funk is the product of the continuous unequal and violent conditions poor people of color face inside Rio’s favelas. There are robust studies about favela funk in Brazilian academia and globally.4 Often, this research focuses on the movement’s criminalization, its ties with drug trafficking, and its aesthetic dimensions. Very few of them, hence, concentrate on the funkeiras. Indeed, the scarce debates regarding funkeiras in Brazilian academia had a lot to do with why I became interested in them in the first place.

As a 1990s kid born in Rio, favela funk was regularly played on the radio and enjoyed at parties, even in middle-class parties like mine. By the time I became intrigued by funkeiras’ performances in 2009, however, I had not attended a favela funk party—a baile—since 2001. The last bailes I had attended were dominated by artists from Cidade de Deus, or City of God, including a funkeira who is prominently featured in this work, Tati Quebra Barraco (Tati House/Shack Breaker). Years later, in 2008, while taking a class in women’s history, occasionally one of us would bring up the funkeiras as an example of a “complicated” negotiation with femininity and sexuality. There was a tendency in most of us to understand favela funk, while acknowledging some of its nuances (such as race and class), as machista (sexist). But that was it. There was no further analysis. It was not until the last year of my masters, in 2009, that my scholarly interest in the funkeiras emerged with full force. I was teaching a course in gender and media at Federal Fluminense University, and toward the end of the semester, I decided to show and discuss Denise Garcia’s 2005 documentary, I’m Ugly but Trendy.5 The class was relatively small, about 16 people, and a lot of the students were actively involved with feminist and LGBTQIA+ movements. Hence, I was hoping to have a good debate on how gender intersects with race and class. To my surprise, a lot of my students who identified as feminists were appalled by the documentary—“this woman just said she’s going to be somebody’s dessert!” Some even thought that the documentary was degrading to funkeiras, who were openly talking and performing about sex to the cameras. I realized that the students’ disturbance was connected to the manner in which funkeiras performed femininity: the direct ways in which they spoke about sex, the way they ←2 | 3→danced, and the way they dressed. These elements, together, seemed to offend white, middle-class, feminine sensibilities.

That was, perhaps, the first of many times yet to come that I became aware of what I now regard as feminist failures. Whatever I had learned about feminism up until that point, and whatever I was teaching about it, was insufficient for understanding the funkeiras’ performances beyond my students’ impression that the documentary was demeaning to them. More than ten years later, my curiosity about the funkeiras, their performances, and their professional paths still intrigue me beyond questions of whether or not they are feminists. I have learned that part of what I perceive to be a scholarly struggle to provide a nuanced understanding of the funkeiras stems from scholars’ tendency to work deductively to “uncover” whether or not those artists are feminists. This book does the opposite of that. Over the next six chapters, I engage this analytical shortcoming as I offer my own consideration of diverse aspects of funkeiras’ performances. A fundamental element of this book’s inductive approach originates from my choice of method.

Critical Methods for the Study of the Funkeiras

I frequently reiterate throughout Bitches Unleashed how much I believe past analyses of funkeiras fall short methodologically. Choosing methods to study their performances was actually very challenging. No single methodology seemed enough, since aside from live and recorded performances, social media has recently become central to funkeiras’ self- and collective expressions. I knew my selections had to be versatile, ethical, and critical, meaning that they had to challenge cartesian thought binaries, such as mind (superior) and body (inferior).6 The considerations featured in this book are, in part, the result of the critical methodological approaches necessary to understand funkeiras in their multidimensionality. Below, I make brief notes about critical ethnography, including interviewing, as well as connective ethnography.

To Dwight Conquergood, “ethnography is an embodied practice” (emphasis in original).7 This perspective calls for “the project of radical empiricism,” in which there is a change in “ethnography’s traditional ←3 | 4→approach from Other-as-theme to Other-as-interlocutor,” which also represents “a shift from monologue to dialogue, from information to communication.”8 Conquergood suggests that our scholarly foci need to move from centers to “borderlands,” “zones of difference,” and “busy intersections” where many identities and interests are not compartmentalized but articulated in multiple ways.9 These changes have been materialized via critical ethnography. Thomas defines critical ethnography as “the reflective process of choosing between conceptual alternatives and making value-laden judgments of meaning and method to challenge research, policy, and other forms of human activity.”10 In comparing critical ethnography to its traditional counterpart, Thomas asserts, “critical ethnography is conventional ethnography with a political purpose.”11

Madison’s critical ethnography builds on the ideas exposed in the previous paragraph through five central questions.12 These inquiries revolve around issues such as the intentions, purposes, and frame of analysis of the researcher; the possible consequences of the researcher’s work, including the potential to do harm; if the researcher maintains dialogue that enables collaboration between herself and others; how the local affects the broader context; and, finally, if the research is committed to social justice—critical ethnography must be committed to politics. The chapters in this book indirectly answer these questions. For instance, I understand the funkeiras as my co-creators and often feature their voices through direct quotes from interviews and song lyrics not simply to illustrate points but also to formulate new knowledge and draw conclusions. If there is something missing from the few studies done on funkeiras, it is certainly their voices.

There are multiple elements in critical ethnography’s methodological sequences, from investigating the researcher’s positionality to tips for preparing for the field.13 I would like, however, to shed light on interviewing, as it is so central to this work. The critical ethnographic interview searches for meanings in ways that go beyond trivial information or “finding the ‘truth of the matter.’”14 Madison points out that the researcher must always keep in mind that interviewees are not “objects.” On the contrary, they are subjects “with agency, history, ←4 | 5→and […] [their] own idiosyncratic command of a story.”15 Consequently, the primary goal of interviewing in critical ethnography is not to find reliable and verifiable information but to illuminate the complexities of “individual subjectivity, memory, yearnings, polemics, and hope that are unveiled and inseparable from shared and inherited expressions of communal strivings, social history, and political possibility.”16 To interview the funkeiras featured in this book, I relied on all three types of critical ethnographic interviews Madison conceptualizes,17 sometimes intentionally and other times as a simple result of where my conversation with a funkeira was headed: (1) oral history, for when an interview is focused on the recounting of events as they relate to the lives of the individuals who experienced them; (2) personal narrative, which deals with the subject’s point-of-view of an event or experience; and (3) finally, the topical interview, which concentrates on individuals’ perspectives on an issue, process, or phenomenon. These distinct approaches to interviewing were useful, as they enabled funkeiras to direct our conversations how they wanted—some funkeiras joined the movement five years ago, and some have had over two decades of experience in favela funk.

Critical ethnography presents a fruitful perspective through which to observe, experience, and write about performances—whether live or mediated. Moreman and MacIntosh’s analysis of Latina drag performances,18 for instance, utilizes Conquergood and Madison’s points about researcher and interlocutor’s co-performativity during fieldwork in order to bring critical ethnography to the page: “We aesthetically (re)present these ethnographic moments on the page not only through our fieldnote vignettes to offer expression to the embodied messages but also to critically evaluate and expose their political implications.”19 Similarly, I offer vivid, embodied descriptions of funkeiras’ performances first as a means to “honor the power and beauty of cultural expression”20 and second as a way to comprehend their political repercussions. Like Auslander, I reject the opposition between live and mediated performances, as well as the assumption that live performances are somewhat superior to mediated ones. Indeed, these categories “are not mutually exclusive.”21 Funkeiras rely heavily on YouTube, for instance, to promote their work. Excluding mediated performances ←5 | 6→from this research would rob funkeiras’ work of their currency and transformations over the years.

Social media has become an extension of the public sphere, a space in which funkeiras not only promote their careers but also narrate their everyday lives. When I first started my fieldwork in June 2013, only very young funkeiras like Pocah had any significant social media presence. Over time, it has become clear that social media offer platforms for funkeiras to perform aspects of their identities that might not interest mainstream media. This book relies on social media to access the performances of funkeiras I was not able to witness in person. To emphasize other digital content from these artists as extensions of their professional and quotidian performances seems appropriate.22 As such, I rely on connective ethnography’s principle, which advocates for a “stance or orientation to internet-related research that considers connections and relations as normative social practices and internet social spaces as complexly connected to other spaces.”23 For that reason, I have been following these artists where they are the most active—on Twitter and Instagram—for at least two years, checking in on their profiles every couple of days to make sure I do not miss anything. Thus, funkeiras’ social media engagement, specifically on those two platforms, are featured in this book as opportunities to further include their voices and perspectives on matters of femininities, race, sexuality, politics, and other topics as they intersect with other aspects of their personal and professional lives.

Who Are the Funkeiras?

Funkeiras are favela funk performers, mostly singers—known as MCs—but also dancers, who are predominantly Black and brown and whose ages vary between early 20s to mid-50s. That is the short answer. The long answer is featured in the six chapters of this book, and each one presents aspects of them as people and performers that hopefully provides a more complete response to the question of who they are. Specifically, I interviewed eight artists—in person, via phone, and over video chat—six of whom are prominently featured in this work: MC ←6 | 7→Kátia, MC Dandara, Deize Tigrona, MC Carol, MC Xuxú, and Linn da Quebrada. Pocah, Valesca Popozuda, and Tati Quebra Barraco are also important for this book, even though I was not able to interview them. I mention other artists in my analyses, but these nine funkeiras persist throughout the following pages. My intention was to include as many artists as possible in a way that their idiosyncrasies did not get lost in the numbers. That means that I absolutely did not intend to include all funkeiras, as favela funk is a very dynamic movement with new artists joining in constantly.

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 246

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433169564

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433169588

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433169595

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433169601

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433169571

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18307

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (May)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XVI, 246 pp., 4 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG