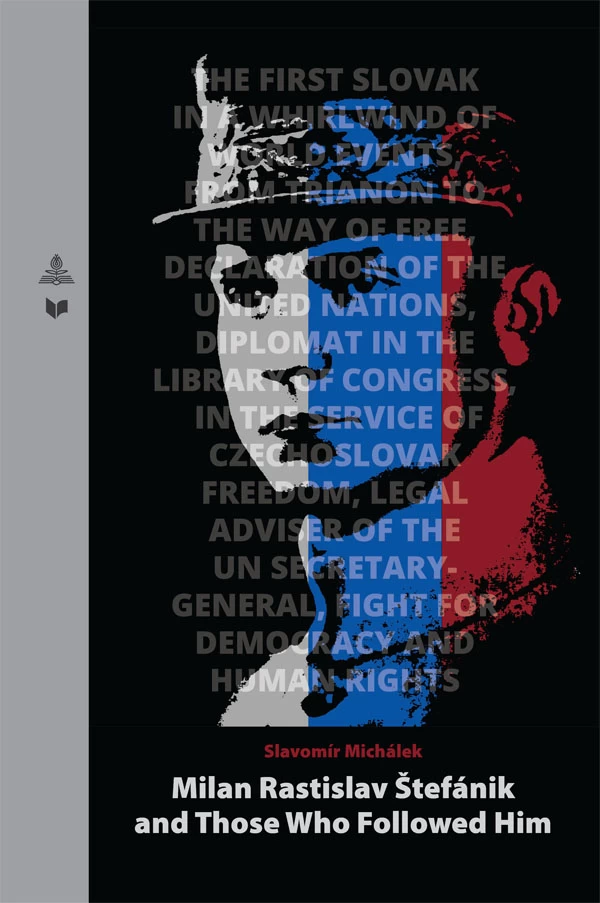

Milan Rastislav Štefánik and Those Who Followed Him

Summary

The entire world began to change and Slovaks were no exception. It is only natural for every nation or state to seek the roots of its national identity. As this identity is embodied by the people and personalities who created it, we perceive the past through their lives. It is a privilege that as a small European nation, Slovaks can say that their dignitaries have succeeded worldwide. It is a great honor that their work can be seen in the Treaty of Trianon, the Declaration of the United Nations, the UN Charter, and everywhere where the voice of freedom and democracy was rising.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction

- European Roots of Slovak Diplomacy

- The First Slovak in a Whirlwind of World Events

- From Trianon to The Way of Free

- Declaration of the United Nations

- Diplomat in the Library of Congress

- In the Service of Czechoslovak Freedom

- Legal Adviser of the UN Secretary-General

- Fight for Democracy and Human Rights

- Conclusion

- Sources and Selected Literature

- Register of Names

- About the Author

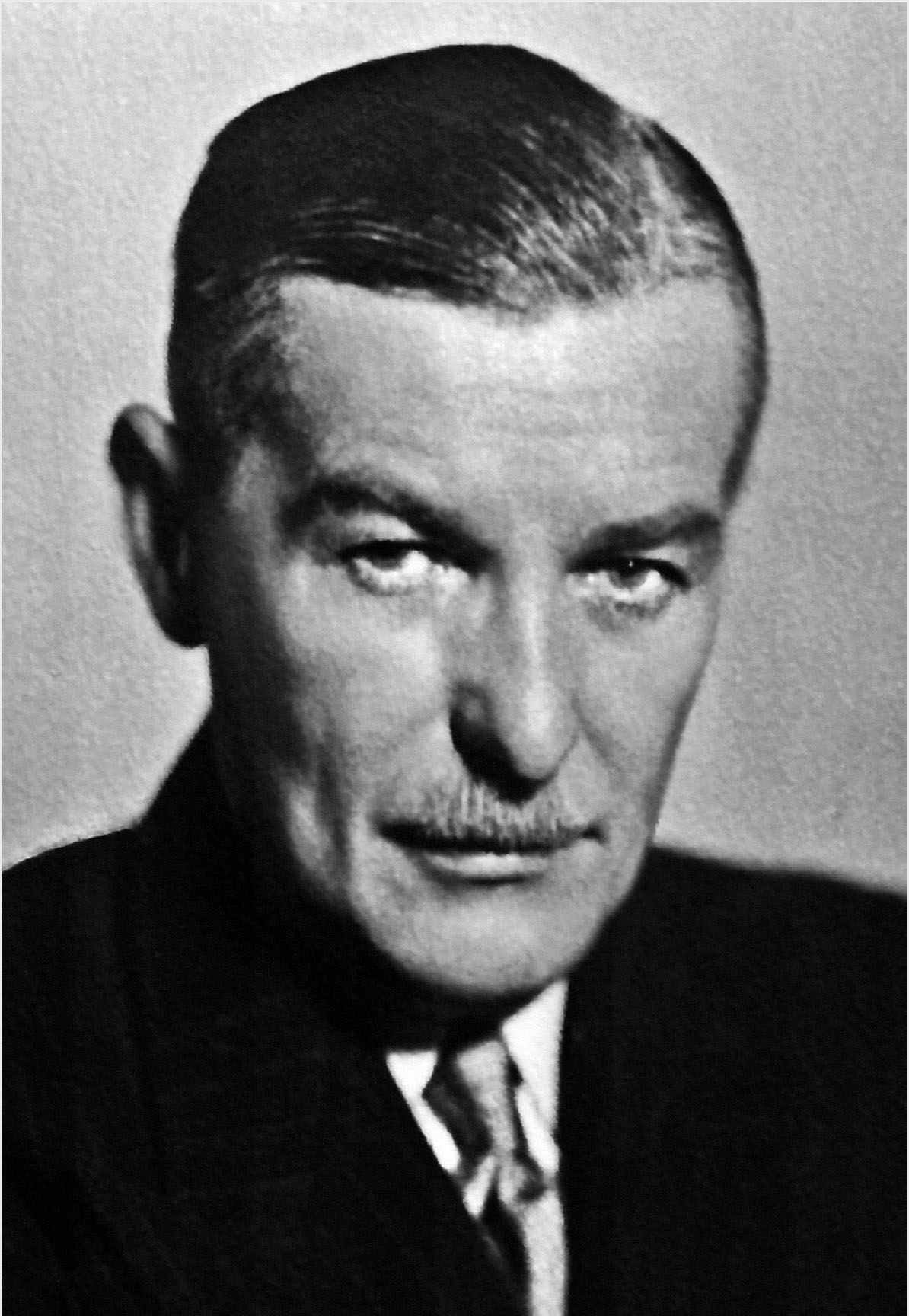

←92 | 93→VLADIMÍR SVETOZÁR HURBAN

Declaration of the United Nations

Vladimír Svetozár Hurban was born on 4 April 1883 in Turčiansky Sv. Martin, the son of Svetozár Hurban Vajanský and Ida, née Dobrovičová.86 His more serious student years began in the autumn of 1893 at a Hungarian secondary school in Bratislava. In 1896, he left as a third-year student with a consilium abeundi (a recommendation to leave, a moderate form of suspension) in his pocket for a Czech Realschule in Hodonín. Later in his life, he recalled his admission examinations and the first few years in Hodonín with nostalgia:

“My knees were shaking because, first of all, I didn’t know that the person with the strict and authoritative appearance standing in front of me, Principal F. Slávik, was a man of kind heart, and secondly, I was shaking because I wasn’t prepared for the examination at all. My knowledge from the Hungarian school was not sufficient, the subjects were different, and I even had problems with the language. The result was miserable. Principal Slávik patted me on the head and told me that the result was sufficient for now, but I would have to catch up and work hard, and I did. There were around five or six Slovaks, especially from Gemer, led by Fedor Albíni, who we liked even just because his beard had started growing. He, as well as Karel Augusta – a “Slovak” Czech, who came from Gemer too, helped me. We lived together.”87

After successfully passing his secondary school final examinations in 1901, Hurban continued with his studies at the Technical University in Vienna. Four years later, he interrupted those studies to join the editorial office of Národné noviny (National Newspapers), continuing in his father’s work who was imprisoned at the time for criticising Hungary. In the spring of 1906, a destiny similar to his father’s befell him as he was sentenced to six months imprisonment in Vacov for protesting against Hungary.

Vladimír Hurban spent ten years in Russia starting in 1908. At first, on the impetus of the Russian General Staff, he organized courses for noncommissioned officers focusing on the clarification and understanding of internal relations with Austria-Hungary in preparation for possible war. At the same time, he taught Hungarian at the General Staff. Hurban was the chief of these courses at the Warsaw Forces Staff until World War I broke ←95 | 96→out. On the day of mobilisation in Russia, 17 July 1914, he was one of the first to join the Tsarist troops, assigned to the active troops as an interpreter. By summer 1916, he was already working in the Czechoslovak rifle brigade command and in May 1917, as a representative of the 3rd Military Regiment of Jan Žižka from Trocnov. He became a member of the Czechoslovak National Council Presidium, specifically its Russian division, and worked mainly in St. Petersburg. Hurban was in charge of locating Czech and Slovak hostages, hiring them as volunteers in the Governorate of St. Petersburg and forming Czechoslovak legionnaire divisions88, to which the Russian Ministry of War expressed their approval on 30 June 1917. On top of that, he worked as chief editor of Slovenské hlasy (Slovak Voices), a newspaper dedicated to the legionnaires and locals, complemented by biweekly newspapers Čechoslovák (Czech-Slovak) and Československé vojsko (Czechoslovak Army) in Moscow, and by the newly issued Československý denník (Czechoslovak Daily) in Kiev.89 His personal correspondence from this period is evidence of elaborate collaboration with Jozef Gregor Tajovský, Bohdan Pavlů, Ivan Markovič and Janko Jesenský. In August 1917, Hurban was ordered by the division of the National Council to move to Moscow, however, the Council division assigned him to Kiev where he was supposed to join the volunteer Czechoslovak revolutionary troops within the Russian armies at the Southwestern Front. He was granted the freedom of residence throughout Russia by the Commissariat.90 This appointment did not last long either as in May 1918, he became an employee of the Eastern forces in Vladivostok based on the order of the Council and was appointed to negotiate with representatives of the Allied powers in Tokyo. He was in charge of registering new legionnaires and organizing their departure to France.91 Though, transporting legionnaires to France was unrealistic due to one significant reason – the lack of vehicles. So they searched for another, so-called American solution and they found it.

Details

- Pages

- 309

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631803165

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631803172

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631803189

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631803196

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16192

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (April)

- Keywords

- History European diplomacy Democracy Totality Freedom Biography Czecho-Slovakia

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2019. 309 pp., 120 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG