George 'Dadie' Rylands

Shakespearean Scholar and Cambridge Legend

Summary

Amazingly for a man with such influence, Rylands was not ensconced in the established Theatre. He taught undergraduates at Cambridge and his own productions were with the amateur Marlowe Dramatic Society there. Nor was his life confined to dramatics and the academic world. He was a fringe member of the Bloomsbury set – firm friends with Lytton Strachey, Virginia Woolf and John Maynard Keynes, all regular correspondents. And his circle of notable friends stretched to a wider group of literati including Maurice Bowra and T. S. Eliot. Rylands died, aged 97, in 1999. We no longer have his irrepressible presence, but he left a palpable legacy in gramophone recordings of all Shakespeare’s plays in which he directed star-studded casts. Now that legacy is augmented by Peter Raina’s study, with its admirable selection of Rylands’ marvellously lucid radio talks (hitherto unpublished) and its sampling of the multitude of letters he wrote and received.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- CHAPTER 1. Early Life and Education

- CHAPTER 2. The Bloomsbury Effect

- CHAPTER 3. A Dialogue on Poetry

- CHAPTER 4. Poetry is not Written with Ideas; It is Written with Words

- CHAPTER 5. BBC Talks: Sydney and Shakespeare

- CHAPTER 6. BBC Talks: Poetry and How to Speak it

- CHAPTER 7. BBC Talks: More Shakespeare

- CHAPTER 8. BBC Talks: with Violet Asquith and on Virginia Woolf

- CHAPTER 9. Essays

- CHAPTER 10. Wits Nurtured In Elizabethan Cambridge

- CHAPTER 11. Shakespeare’s Image of Man and Nature

- CHAPTER 12. Shakespeare’s Poetic Energy

- CHAPTER 13. A Man of the Theatre: “The Stage has No Secrets for Me”

- CHAPTER 14. Lecturer and Tutor

- CHAPTER 15. Dadie’s Rooms at King’s

- CHAPTER 16. Domus Bursar

- CHAPTER 17. Letters: The Virtues of Friendship

- CHAPTER 18. Letters: Keeping Up with Bloomsbury

- CHAPTER 19. Last Scene of All

- Epilogue: “Nestor by the Cam”

- Bibliography

- Index

Illustration 1. George Rylands as an undergraduate (1920)

Courtesy of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Courtesy of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Courtesy of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Illustration 4. George Rylands with Lytton Strachey (1928)

Courtesy of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Courtesy of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

←ix | x→Courtesy of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

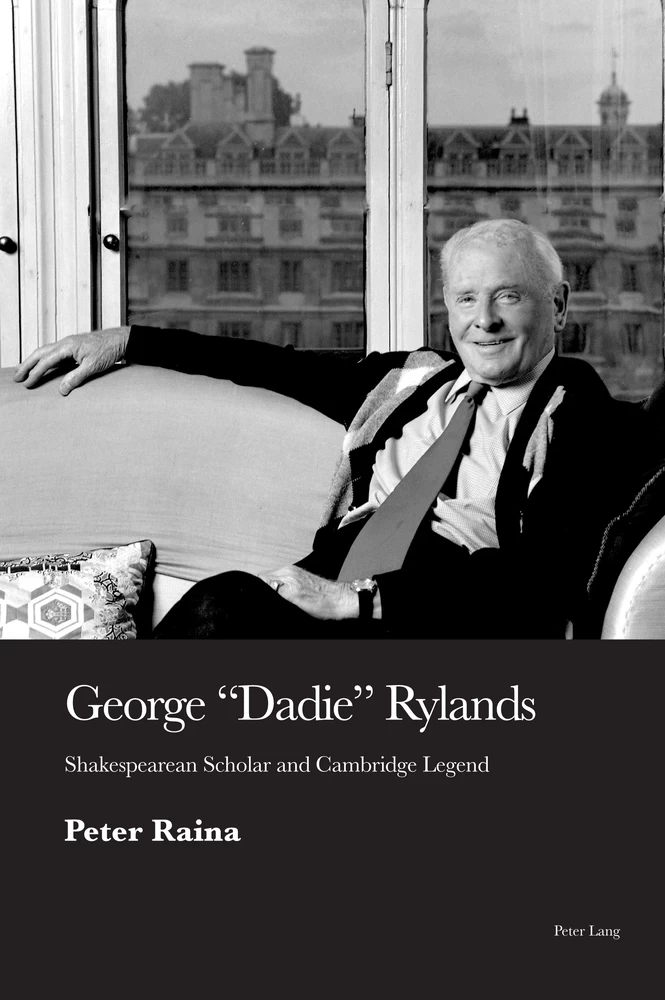

Illustration 7. George Rylands sitting in the window seat of his room, King’s College, Cambridge

Photograph by Granville Davies.

Reproduced by kind permission of Granville Davies.

Courtesy of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge

Illustration 9. Helen, Viscountess D’Abernon

by Henry Van der Weyde, photogravure by Walker & Boutall, published 1899

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 10. Dame Peggy Ashcroft, as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet

by Howard Coster, 1935

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 11. Violet Bonham Carter, Baroness Asquith of Yarnbury

by Bassano Ltd., 30 June 1947

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 12. Sir Maurice Bowra

by Henry Lamb, 1952

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

←x | xi→--by John Gay, 1948

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 14. Dame Margot Fonteyn

by Cecil Beaton, 28 October 1950

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 15. Sir John Gielgud

by Bern Schwartz, 1 May 1977

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 16. Sir John Gilegud; Dame Peggy Ashcraft

by Howard Coster, 1935

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Bassono Ltd., 16 April 1935

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 18. Lydia Lopokova

by Bassano Ltd., 21 August 1918

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 19. Laurence Olivier as Hamlet and Vivien Leigh as Ophelia in Hamlet

by an unknown photographer, 1937

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

←xi | xii→--Illustration 20. Harold Pinter

by Justin Mortimer

oil on canvas, 1992

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 21. Rachel Kempson, Lady Redgrave; Sir Michael Redgrave

by Bassano Ltd., 1937

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 22. Victor Rothschild, 3rd Baron Rothschild

by Bassano Ltd., 23 March 1965

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 23. Lytton Strachey

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1911–1912

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 24. Lytton Strachey; Virginia Woolf; Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, June 1923

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Illustration 25. Virginia Woolf

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1917

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

The present work is not a full life of George “Dadie” Rylands. Any attempt to accomplish that would entail detailing the minute particulars of his character, and we make no attempt at such an undertaking here. Nor do we intend to mention his faults. That, as Dr Johnson reminds us, must fall to the care of a man’s intimate friends. Only those “who live with a man can write his life with any genuine exactness and discrimination,” Johnson once told Boswell.

For Rylands, there was such a man in Noel Annan.1 He and Rylands got to know each other when Annan came up to King’s College, Cambridge in 1935 to read History. Annan “became platonically devoted” to Rylands “for the rest of his life”. Much later, after the latter’s death, Annan wrote a twenty-two-page biographical essay about him. It is a masterpiece.2 In the essay Annan covers every aspect of Rylands’ life: his childhood, his academic career, his work as an actor and producer of plays, and his love affairs with both men and women. Annan appears to have had a deep understanding of his subject in all the phases he went through. He tells us how Dadie imbibed English poetry with his mother’s milk and describes how, in 1928, “he began a series of productions that made the Marlowe Society renowned as the nursery where those who were to become famous in the theatre learned to speak Shakespeare’s verse”. Nor did Dadie confine himself to Shakespeare: he produced and directed plays by George Bernard Shaw and T. S. Eliot, as well as Ancient Greek drama. Annan describes how Dadie brought poetry to a wider audience by holding recitals all over the country: he had “a light resonant voice; he never dramatised or used elocutionary tricks and was always intelligible, taking care never to drop ←xiii | xiv→the voice at the end of a sentence”. Dadie also gave lectures. These, “though packed with material, were original in their effect, their delivery and their arrangement rather than in the argument itself or the method of analysis”. Dadie was “not a great orator: he did not move well; but he had a stage presence and he could hold an audience by his voice alone.”

It was Dadie’s mother, Annan tells us, who “possessed his soul”. She “disciplined him strictly” and “spoilt him by encouraging his waywardness”. Between the two “there arose strong emotions of love and hate”,3 for, ever after, between “him and his desires came the curse of his mother”.4 Rylands’ life, Annan asserts, “was tragic. Guilt denied him any happiness or love that he might have found in his sexual encounters. Drink alone released him from this sense of guilt, but when it operated it released other evil potencies which ran like rats among his guests. He became quarrelsome, pettish and jealous […], he used his tongue as his mother had taught him, to sting those about him.”5 Rylands “did not believe that sex and love were compatible. He would deny that affectionate, trusting, adoring married couples really experienced sexual love. […] He fell in love only three times and suffered much; and he was so racked by guilt and a sense of physical shame he sometimes became impotent. He identified sex with lust, not love, with danger and with frenzy. Someone who went to bed with him described it as “like being in a rugger scrum”.6 Yet, no matter how miserable Dadie’s sexual life may have been, his troubles do not seem to have affected his literary scholarship. His private life lies outside the sphere of our study. Whether he liked men more than women, or whether he fell in love with men alone does not concern us. We have not even felt any need to investigate what Virginia Woolf observed when she first met Rylands: “Dady” [sic], she wrote, “has an ingratiating manner of pawing ladies old enough to be his mother.”7

←xiv | xv→Our main intention is to draw a portrait of a great Shakespearean scholar. This we have attempted to do through the medium of Rylands’ BBC talks, his essays, and his books. Whatever is “peculiarly solemn” in their contents increases the insights we get into his mind. We have reproduced letters to Dadie Rylands from distinguished men and women, all of whom conveyed not only their affection and devotion, but also acknowledged the rich contribution Rylands made both to Shakespearean literature and to practical performance in the British theatre.

George Rylands was already relishing the beauty of Shakespeare’s plays while he was at Eton College, where he was also trained in public speaking. He won College prizes for acting and for rhetoric. When he came up to King’s College, Cambridge, he first read Classics, but then switched to English Literature, in which he was tutored by the well known Cambridge classicist Frank Lucas. Lucas instilled a love of English poetry in Rylands, who became obsessed with Milton, Wordsworth, and Tennyson. Later, when he read The Wasteland, he developed an equal admiration for T. S. Eliot. Rylands wrote his own poems too, first in blank verse, then in rhyme. But theatre became his greatest passion, and he involved himself passionately in the Cambridge Marlowe Dramatic Society, and performed in several of the plays it put on. Primarily he acted in female roles. His voice was melodious, and fascinated the audiences. Among those who took a fancy to Rylands was Lytton Strachey. This led to a very close friendship and deep affection between the two. Strachey introduced Rylands to the Bloomsbury group, and he got to know Virginia Woolf, Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, and Vanessa Bell. These Bloomsbury figures were to become lifelong friends.

Early on, Rylands realized that his talent lay not in writing his own poems, but in interpreting the works of the great poets before him. He established himself as a remarkable critic, especially in expounding the meaning of Shakespeare’s works. In 1928 he published his major study Words and Poetry. Here he discussed “word values” and “ornament” in poetry. Poetry, he argued, was not written with ideas, but written with words. He noted three special features it possessed. Simplicity was the key one – poetry should be direct. The next to be prized was brevity – poetry had wit as its soul, with metre lending grace. The third feature was thought, with similes ←xv | xvi→and metaphors beautifying the language. Rylands illustrated his thesis with ample citations of Shakespeare’s diction and style.

Rylands elaborated further in a series of lectures aired on the BBC. Speaking on Shakespeare and His England, he maintained that Shakespeare was not a philosopher, not a politician, not a sectarian; rather a man who espoused tolerance, sympathy, and humour. And in Shakespeare Yesterday and Today, Rylands observed how the task and method of acting had changed. Acting should be more true to the original; above all it should be “better spoken”: “Speak the Speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to you.” As an illustration of the art of acting Shakespeare, Rylands talked at length with John Gielgud on the radio. And, reviewing a performance of Othello in 1930, he complained: “the phrasing was slurred; the poetry disappeared.” The dramatist must borrow “our ears”; as an artist, his “pigments and clay are flesh and blood, his instrument the human voice”.

In 1939 Rylands brought out an anthology of Shakespeare’s works: Image of Man and Nature. The anthology uses passages of Shakespeare to mirror how we react to the various circumstances of life, and the general passions by which all minds are agitated. Rylands explores the idiom, the rhythms, even single words of Shakespeare’s language. His stress is on two elements: the thing said and the way in which it is said. He is interested not so much in the forms of the verse and prose, but in the content and the style. He highlights the sheer poetic energy in Shakespeare: figurative language, flights of imagination, and rollercoasters of dramatic effect all need to be noted and absorbed.

Rylands himself enjoyed directing plays. He soon showed how remarkable a director he could be. The Theatre world sought his advice. Celebrities like Peggy Ashcroft, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, and Michael Redgrave often wrote asking him to help them. For the outstanding contribution Rylands made to the arts he was appointed CBE in 1961 and Companion of Honour in 1987.

The close friendships Rylands maintained with an enormous number of distinguished men and women were ties he cherished. He admired these talented friends, and they admired and loved him back. The letters Rylands received are most enchanting. Peggy Ashcroft wrote:

←xvi | xvii→When the actors drive you mad,

Darling Dadie don’ t be sad.

Maurice Bowra confided in him. T. S. Eliot expressed thanks “for your review which seems to be excellent. In some ways it is like your poetry.” John Gielgud wrote:

I must tell you, by the way how enormously I admired your anthology. … I am doing a lecture which includes many of the quotations which you have. Also I hope one day to have the pleasure of seeing a Shakespeare production of yours. I hear Macbeth was magnificent. Perhaps we may work on one of the plays together.

Peter Hall replied to a message: “Your letter is one to treasure, thank you so much.” A couple of months before his death, Maynard Keynes sent a touching goodbye: “Farewell dear child … minion of the Muses.” Vivien Leigh wrote: “Dearest Dadie, your letter touched and encouraged me more than I can tell, thank you.” Also in a reply, W. Somerset Maugham exclaimed: “Your letter was a most joyful surprise …”. Laurence Olivier confided:

I have never been clear about the pronunciation of Latin in Shakespeare and as I am about to launch Love’s Labour I had better know what I am about in this particular ingredient. Is it ‘old’ or is it ‘new’? For instance for: veni, vidi, vici.

After a reunion, Michael Redgrave wrote to say: “I couldn’t let a day go by without letting you know how happy I was to meet you again, and how grateful.” Lytton Strachey’s letters indicate the warmth of his particular friendship with Rylands – we have reproduced 110 of these in the present study. Virginia Woolf was a correspondent too, on one occasion writing:

I suppose you are writing a novel and a poem and carrying on a vast complicated [mass] of affairs. I go on plodding with my poor nose to the grindstone. So please come and be charming to your poor drudge.

George Rylands was a charming host: “Thank you so much for your enchanting hospitality,” declared Maurice Bowra. Rylands was also a delightful guest. Somerset Maugham, whom Rylands often visited, tells us that he belonged to the guests:

←xvii | xviii→who are happy just to be with you, who seek to please, who have resources of their own, who amuse you, whose conversation is delightful, whose interests are varied, who exhilarate and excite you, who in short give you more than you can ever hope to give them and whose visits are only too brief.8

Such a guest was George Rylands.

Rylands was a brilliant scholar, generous, and devoid of envy. He was sensitive but displayed perfect frankness in his contacts with people. He was endearing to everyone he met, and always good company. When he celebrated his ninetieth birthday, he received more than a hundred letters and cables congratulating him. He reached the ripe old age of 97, and retained his charm and composure till the very end.

Samuel Johnson maintained that “if a man is to write A Panegyrick, he may keep vices out of sight; but if he professes to write A Life, he must represent it really as it was.” Perhaps the following pages will show what he means.

Peter Raina

←xviii | xix→1 Noel Annan (1916–2000), Provost of King’s College, Cambridge, 1956–66, Provost of University College, London, 1966–78.

2 Noel Annan, “The Don as Performer – George Rylands” in The Dons. Mentors, Eccentrics and Geniuses (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), pp. 170–92.

3 Ibid., p. 181.

4 Ibid., p. 182.

5 Ibid., p. 182.

6 Ibid., p. 182–3.

7 Entry 11 September 1923. The Diary of Virginia Woolf. Edited by Anne Olivier Bell, assisted by Andrew McNeillie. Volume II: 1920–1924 (The Hogarth Press: London, 1978), p. 268.

8 W. Somerset Maugham, The Vagrant Mood (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1952), pp. 217–18.

I am chiefly indebted to the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge for access to “the papers of George Humphrey Wolferstan Rylands” held in the Archives Centre of the College, and for copyright permission to reproduce texts George Rylands wrote. I must acknowledge a special obligation to Peter Jones, Fellow Librarian and to Patricia McGuire, Archivist. I can hardly find words to express my profound thanks to Patricia. She has been extraordinarily kind, helpful and meticulous in securing the material needed for my study, uncommonly generous and efficient in answering my enquiries, and solicitous in suggesting methods for getting around problems.

Copyrights

I must thank the following copyright holders for permission to reproduce the unpublished material in this book:

1. Unpublished writings of J. M. Keynes, copyright the Provost and Scholars of King’s College Cambridge 202–2020.

2. The agreed 800 Words from Noel Annan: Three Letters by Noel Annan, published by the Archives Centre, King’s College, Cambridge, © The Estate of Noel Annan and reproduced by permission of the Estate, c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN.

3. Sharon Rubin, Permissions Manager, Peters Fraser & Dunlop, 55 New Oxford Street, London, WC1A 1BS. George Rylands’ unpublished texts.

4. Granville Davies: Photograph of George Rylands.

5. Baron Jacob Rothschild: unpublished letters of Baron Victor Rothschild to George Rylands.

6. Richard Olivier, Artistic Director, Olivier Mythodrama, London: unpublished letters of Sir Laurence Olivier to George Rylands.

7. The Hon. Virginia Brand, © the trustees of the Asquith Bonham Carter papers at the Bodleian Library: unpublished letters of Lady Asquith to George Rylands.

8. The Hon. Virgina Brand: unpublished letters by Lord Mark Bonham Carter to George Rylands.

9. Ian Bradshaw, Partner, Goodman Derrick LLP, London: unpublished letters by Sir John Gielgud to George Rylands by kind permission of the Trustees of the Sir John Gielgud Charitable Trust.

10. Julie Crocker, Senior Archivist (Access) Royal Archives, Windsor Castle: unpublished letters by the Treasurer to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother to George Rylands.

11. Jeffrey Hackney, Archvist, Wadham College, Oxford: unpublished letters from Sir Maurice Bowra to George Rylands.

12. Sheba McFarlane, Administrative Assistant, The Society of Authors, London: the works of both Virginia Woolf and Lytton Strachey are now out of copyright (in the UK).

13. Claire Boreham, Archivist, BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham Park, Reading: unpublished George Rylands scripts.

14. Joshua Insley, Interim Archivist, Eton College, Windsor.

15. The National Portrait Gallery, London.

16. Tim Evenden, The Keep, East Sussex Record Office, Woollards Way, Brighton.

Copyright Problems:

There has been a copyright problem with regard to three authors. No one knows who owns Peggy Ashcroft’s copyright. I have consulted the testament (probate registry) – there is nothing in there. I have tried to locate Ashcroft’s son and granddaughter in Canada – no response. I tried to contact two other granddaughters in Paris (one a singer, the other a journalist), contacting them through their agents, who forwarded my request – again no response.

With Michael Redgrave the situation is similar. I attempted to contact Vanessa Redgrave through her agents several times and the request was forwarded to her, but there has been no response.

No one knows who owns Raymond Mortimer’s copyright.

Details

- Pages

- XXII, 492

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781789976939

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789976946

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789976953

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789976960

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16401

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (March)

- Keywords

- Shakespeare The Theatre Bloomsbury Cambridge

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2020. XXII, 492 pp., 8 fig. col., 17 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG