Rethinking the Australian Dilemma

Economics and Foreign Policy, 1942-1957

Summary

There is broad acceptance that the end of British Australia only occurred in the 1960s and that the initiative for change came from Britain rather than Australia. This book rejects this consensus, which fundamentally rests on the idea of Australia remaining part of a British World until the UK attempts to join the European Community in the 1960s. Instead, it demonstrates that critical steps ending British Australia occurred in the 1950s and were initiated by Australia. These Australian actions were especially pronounced in the economic sphere, which has been largely overlooked in the current consensus. Australia’s understanding of its national self-interest outweighed its sense of Britishness.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Graphs and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms Used

- Part I Kinship

- Introduction – The Anzac Dilemma

- The Dilemma

- Major Themes

- Periodisation and Turning Points

- Structure

- 1 The Dependent Dominion: Australia in 1941

- Introduction

- Australia’s Britishness

- The Impact of Ottawa

- The Dependent Dominion

- Australian Prime Ministers and America

- Australia through the Eyes of American Diplomats

- Conclusion

- Part II Estrangement

- 2 The War Economy

- Introduction

- U.S. Trade and Article VII

- Industrial Expansion

- Changing Relative Stature of the American, British and Australian Economies

- The Role of Larger Government

- Conclusion

- 3 “Australia Looks to America,” 1942–43

- Introduction

- The U.S.-Australia Relationship – Mutual Expedience

- The Lack of U.S.-Australian Affinity

- The Revival of Anglo-Australian Relations

- Lend-Lease and Economic Tensions

- Conclusion

- Part III Reconciliation

- 4 “Recovering Our Lost Property,” 1943–44

- Introduction

- Britishness and Australian Self-Interest

- The Benefits of Acting through the Commonwealth

- Australia’s Economic Links to Britain

- Anti-Americanism

- Commonwealth Institutional Ties

- The ANZAC Treaty

- British Involvement in the Pacific War

- Commonwealth Planning for Bretton Woods

- Conclusion

- 5 The Chifley Government: Policy Motivation

- Introduction

- The Benefits of the Sterling Area

- The Commonwealth as an Institution for Australian Interests

- Industry Policy

- Defence Policy

- ALP and Anti-Americanism

- The Risks of Appearing Anti-British

- Conclusion

- 6 Post-War Reconstruction and Economic Choices, 1945–49

- Introduction

- The Risks of Reliance on Britain

- The 1947 Sterling Crisis

- Australian Reaction to the Prospect of a Western Union

- Self-Interest and Anti-Americanism

- Petrol Rationing

- Conclusion

- Part IV Separation

- 7 Percy Spender and the Interconnection of Economics and Foreign Policy, 1949–50

- Introduction

- Spender as Minister for External Affairs

- Economics and Foreign Policy

- Anglo-American Differences

- Spender and the Australian Dilemma

- Spender and the Colombo Plan

- Korea

- ANZUS

- Conclusion

- 8 National Development and the Sterling Bloc, 1951–52

- Introduction

- National Development and Defence

- The 1952 Commonwealth Finance Ministers’ Conference

- “Dealing with an Enemy or a Friend?”

- The 1952 Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference

- Could Only Menzies “Go to China”?

- Conclusion

- 9 Aligning with America, 1952–57

- Introduction

- Economics –Continuities and Turning Points

- Australia’s Trade Relationships with Japan and Britain

- Defence Alignment – Managing Anglo-American Differences

- The Radford Bombshell

- Defence Reviews

- Menzies and Suez

- The British Reaction

- Conclusion – The Dilemma Resolved

- Menzies and His Britishness

- Choosing with Whom to Trade

- Choosing Whom to Fight Alongside

- Britishness, Economics, and Self-Interest

- Index

List of Illustrations

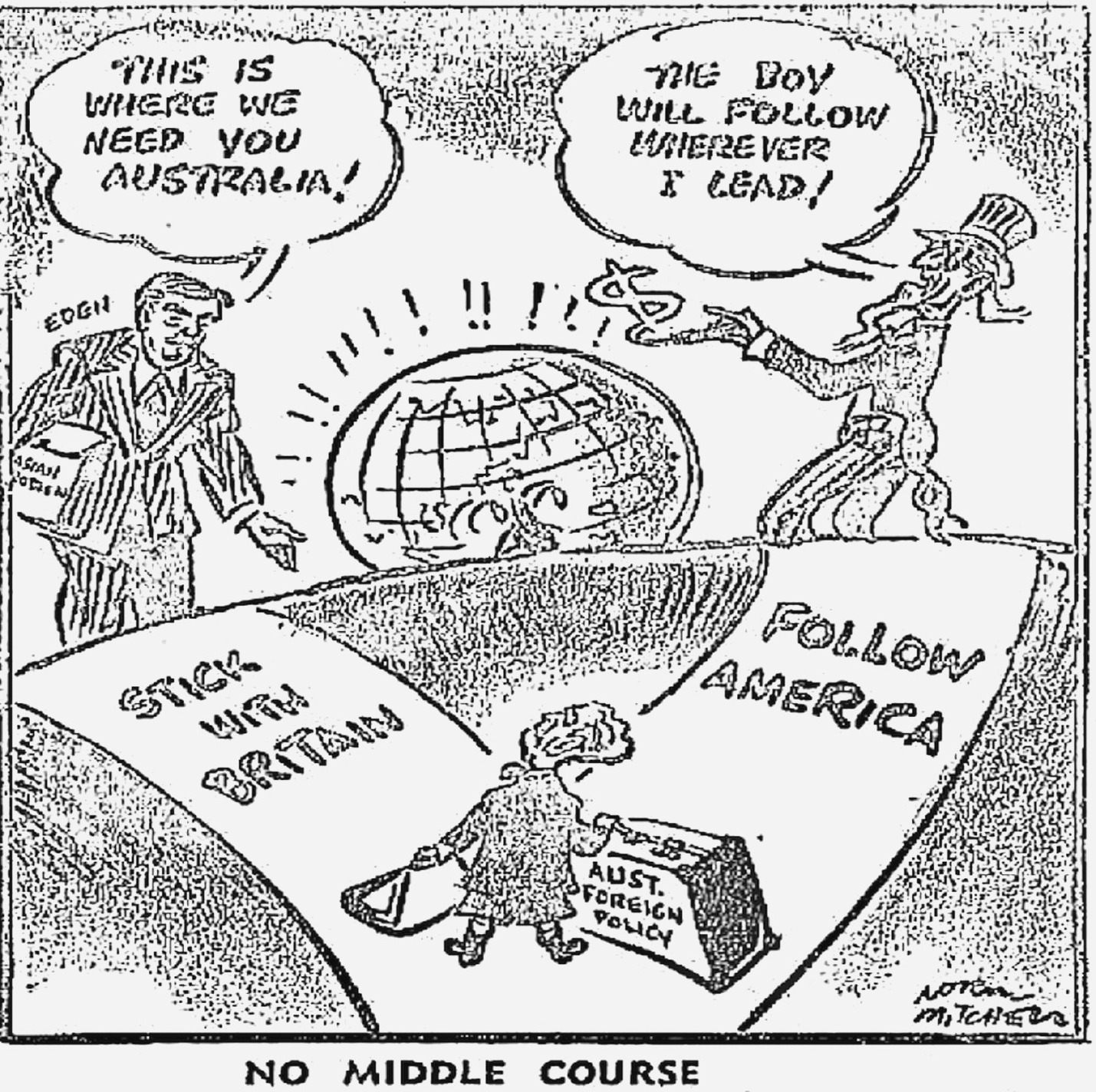

No Middle Course, Norman Mitchell, The News (Adelaide), 3 June 1954

In Darkest America, Norman Lindsay, The Bulletin, 17 January 1940

No Offence, Mum, John Frith, The Bulletin, 31 December 1941

What -No Chaperon? Sid Scales, Otago Daily Times, 27 September 1952

List of Graphs and Tables

Graph 1Australian Trade Partners – 1892–1928

Graph 2Australian Trade Partners – 1892–1939

Graph 3% Share of Australian Exports

Graph 4% Share of Total Australian Trade

Table 1Australian Trade 1892–1939

Table 2Index of Australian Export Concentration 1913–1938

Table 3Australian Trade 1892–1959

Table 4Growth of Australian Government 1939-mid 1950s

Table 5Comparative Defence Expenditure 1953–1957

This book explains how and why, between 1942 and 1957, Australian governments shifted from their historical relationship with Britain to the beginning of a primary reliance on the United States. It shows that, while the Curtin and Chifley Australian Labor Party (ALP) governments sought to maintain and strengthen Australia’s links with Britain, the Menzies administration took the decisive steps towards this realignment.

The dominant feature of the Australian governments’ foreign policy was a search for security. First, Japan, and then the Cold War in Asia had made the region more dangerous, at the same time as Australia’s traditional protector, Britain, proved less willing and able to meet these threats. However, while military strengths and cultural links were significant, domestic economic reconstruction was at the core of Australia’s search for security. The Menzies government saw development as not just as an economic goal but critical for Australia’s long-term security. This policy served to push Australia towards the dominant United States and its ally, Japan, and away from the weaker Britain.

←xv | xvi→There is broad acceptance that the end of British Australia only occurred in the 1960s and that the initiative for change came from Britain rather than Australia. This book rejects this consensus, which fundamentally rests on the idea of Australia remaining part of a British World until the UK attempts to join the European Community in the 1960s. Instead, it demonstrates that critical steps ending British Australia occurred in the 1950s and were initiated by Australia. These Australian actions were especially pronounced in the economic sphere, which has been largely overlooked in the current consensus. Australia’s understanding of its national self-interest outweighed its sense of Britishness.

In The Government and the People, 1942–1945, Paul Hasluck compares his delay in delivering the second volume of his Official History of the war to the kangaroo, which he explains:

Prolongs the period of gestation when the season is unpropitious, and the offspring due to be born this season may not come until the next season, not by deliberate choice of the parents but by the dispensation of Nature. A similar phenomenon may be noted in the case of this volume.1

Hasluck uses this occurrence to justify his eighteen-year delay. How then should I explain an over thirty-year deferral between my initial plans to carry out historical research and the eventual outcome represented by this book? Perhaps it would be easiest to say that life in general rather than any specific gestation period was responsible! It also means that some of the people whom I consider to be initiators of this work have probably long forgotten their acts of inspiration. Fortunately, others have continued to be involved or became involved more recently and so will be more aware of their contribution. I want to take this opportunity to acknowledge their assistance.

←xvii | xviii→Several people are responsible for initially generating my interest in carrying out the research and writing involved. I want to thank them. As my undergraduate tutor at Leeds University, the late Phil Taylor was the first to make me consider what working as a historian would be like. Marne Hughes-Warrington convinced me that I should do it. Having started my doctoral research, I was delighted to find that existing experts were happy to take the time to discuss their work and even to read my drafts; in particular, Roger Bell, David Lee, and Frank Bongiorno provided coffee and advice. I greatly appreciated both.

This book began its life as my PhD thesis. My supervisors, Andrea Benvenuti and Lisa Ford, were towers of strength and consistent sources of advice. I’m not sure whether they understand that this would not have been finished without them, but I do.

I want to thank Jatinder Mann for suggesting that I consider preparing it as a book in his series, Studies in Transnationalism, and also for helping me navigate that process with good humour and regular insightfulness. It became a book due to Peter Lang Publishing and I have appreciated Meagan Simpson and Sarath Kumar’s calm advice and rapid responses to my numerous queries.

I have always enjoyed libraries and appreciated their role in civil society. This is fortunate, as I have spent what seems to be an overwhelming proportion of my recent life in libraries and archives across the globe. These include the National Archives of Australia, the National Library of Australia, the Reserve Bank of Australia Library, UNSW, Macquarie University, Ascham School, Woollahra and the City of Sydney Libraries, the U.S. Library of Congress and National Archive, and the UK National Archive. I thank the staff working at these institutions and those who ensure that they are appropriately funded.

However, despite all this assistance, ultimately this book would not have been possible without Sian and Liam’s ongoing support, intellectual stimulation and love. They have been there for the entire journey and have calmly accepted its every stage. I am sure they are pleased that it is finally over!

Needless to say, none of the above bears any responsibility for the opinions and particularly any errors or omissions expressed here, which are mine alone.

Note

1Paul Hasluck, The Government and the People, 1942–1945 (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1970), ix.

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms Used

ADB Australian Dictionary of Biography.

AIF Australian Imperial Force.

ALPAustralian Labor Party.

ANZAM Agreement between Australia, New Zealand and Britain for the defence of British-ruled Malaya.

ANZSANA Australia New Zealand Studies Association of North America.

ANZUS The Australia, New Zealand and U.S. (ANZUS) Treaty is a multilateral military alliance signed in 1951. It binds members to cooperate on Asia-Pacific security.

CRO Commonwealth Relations Office (UK).

DAFPDocuments on Australian Foreign Policy.

DFAT Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia).

DPWR Department of Post War Reconstruction (Australia).

DWOI Department of War Organisation of Industry (Australia).

EECEuropean Economic Community, formed through the 1957 Treaty of Rome by France, Germany, Italy and the Benelux countries.

EFTA European Free Trade Area. Founded in 1960 by Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

FRUSForeign Relations of the United States (U.S. State Dept. publication).

←xix | xx→GATT General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

GDPGross Domestic Product.

GM-HGeneral Motors-Holden.

IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

IMF International Monetary Fund.

ITOInternational Trade Organization.

LoC U.S. Library of Congress.

MFNMost Favoured Nation. Agreements that require the recipient country to receive equal trade advantages as the “most favoured nation” by the country granting such treatment. For Australia, MFN ranked behind Imperial Preference, i.e. so called most favoured was actually second best.

MHR Member of the House of Representatives (Australian government).

NAA National Archives of Australia.

NATONorth Atlantic Treaty Organisation, established in 1949.

NLA National Library of Australia.

NSC U.S. National Security Council.

PWC Pacific War Council. Based in Washington.

RAAF Royal Australian Air Force.

RANRoyal Australian Navy.

RBA Reserve Bank of Australia.

SEATOThe South East Asia Treaty Organisation. An agreement for mutual defence between Australia, France, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand, Britain and America signed on 8 September 1954.

SWPA South West Pacific Area.

UKUnited Kingdom. I have used Britain and the United Kingdom interchangeably in this book as shorthand for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

UKNA United Kingdom National Archive (previously known as PRO (Public Records Office)).

UNUnited Nations.

U.S.United States. I have used America and the United States interchangeably as shorthand for the United States of America.

USNUnited States Navy.

USNA U.S. National Archive.

WTO World Trade Organisation.

Kinship

Introduction – The Anzac Dilemma

“Some inadequately observed consequences of the decline of British power, with special reference to the Pacific area.”1

In the early 1950s, the historian Frederick Wood explained the choices forced upon Australia and New Zealand by British decline. Previously, he said, “we took for granted the naval and economic strength of Great Britain, and on that twofold foundation we built free and prosperous countries.” But this British preeminence no longer existed; America was the dominant military and economic power. Britain’s decline led to what he called the “Anzac dilemma.” Australia could be forced to choose between the British Commonwealth and the United States. The dilemma was masked when Britain and America stood together but, if they seriously diverged, “the results for the Pacific Dominions would be calamitous.”2

←3 | 4→While Wood’s primary focus was on New Zealand, this book explores how Australia attempted to resolve the dilemma from 1942 to 1957. It finds that, contrary to the current historical consensus and public political statements at the time, which emphasise ongoing attachment to Britain, in the 1950s, Australia demonstrated an increasing tendency to follow America. This choice was clear to many contemporaries. The Adelaide News, soon after Rupert Murdoch assumed control, summarised the “dilemma” in 1954. A front-page editorial asked “the 64-dollar question … Is Canberra more concerned with keeping in step with Washington than with her traditional ties with Britain?” An accompanying cartoon illustrated the dilemma. Should Richard Casey, Australia’s Minister for External Affairs, take Uncle Sam’s dollars and the path entitled “follow America,” or respect the advice of the British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, and “stick with Britain”? As its title claims, there was “No Middle Course.”3

No Middle Course. Source: The News (Adelaide), 3 June 1954

←4 | 5→Australia’s pro-American tendency grew during Robert Menzies’s administration, elected in December 1949. It was revealed in a series of meetings and actions in 1957 illustrating how, despite the ongoing familial ties of empire, the Menzies government’s Britishness had been overwhelmed by economic and geo-strategic realities. The Japanese advances in early 1942 had first made the Anglo-Australian rift apparent, but both sides papered over these fissures when the threat receded. However, the Menzies government came to believe that Australian national interest could, ultimately, only be secured by America rather than Britain. This concern reached an apogee in 1957.

Australia’s choice was demonstrated at the Canberra SEATO Council meeting in March 1957.4 John Foster Dulles, the American Secretary of State and the British Lords Home and Carrington, Secretary for Commonwealth Relations and High Commissioner respectively, attended.5 Casey, with deliberate understatement, described their time with the British as “not very pleasant.”6

Home and Carrington sought to justify significant British defence cuts in the Far East. William Worth, who later in 1957 became Deputy-Secretary to SEATO but was then an Assistant Secretary in the Prime Minister’s Department, set out the questions to pose to Britain. Illustrating Australian concerns, he suggested the preamble to the defence questions be just “who do they think they are kidding?” He compared the British government’s position to its strategy less than two decades earlier, which, from the Australian perspective, had eventually doomed Singapore: “1940 all over again with its catastrophic complacency.”7 In contrast, although America had been reluctant to accept open-ended commitments, on this occasion, Dulles emphasised U.S. commitment to the region and its security pacts:

Let there be no doubt in any quarter … that the American nation is united in its determination to respond to our obligations under these pacts. Also that determination is backed by power in being and in useful places.8

Later that year, Australia announced its defence alignment with America, a commercial agreement with Japan that led to it replacing the United Kingdom as Australia’s principal export destination, and a rejection of British proposals for greater coordination of Commonwealth forces in South-East Asia. As Casey explained to Duncan Sandys, British Secretary of State for Defence, in declining these overtures, Australia explicitly prioritised its reliance upon American economic and military strength above British race patriotism:

←5 | 6→For survival Australia had to rely on the United States. They were the only nation in command of great forces in the area and we could rely on no one else for massive aid. Australia is just as warmly attached as ever to the United Kingdom, but these are facts of life.9

Menzies repeated this rejection. He explained to Harold Macmillan, the British Prime Minister, that “the main stream of our policy” was dependence on America for security.10 However, accounts of Australian policy in the 1950s generally omit this turn to America. Indeed, a recent article, summarising the papers given at a conference on British Australia, concluded that:

There is a large degree of consensus among the historians about the timing of the end of British Australia, and only mild disagreement about how that end came about … all agree on the 1960s [when Britain tried to join the EEC] as decisive, and all locate the initiative more in Britain than Australia. Australians did not so much seek independence as have it thrust upon them by the reorientation of Britain’s place in the world.11

I reject this consensus. This book demonstrates that critical steps ending British Australia occurred in the 1950s and were initiated by Australia. These Australian actions were especially pronounced in the economic sphere, which the consensus has mostly overlooked. I explain how and why, by 1957, Australian governments had shifted from their historical relationship with Britain to the beginning of a primary reliance upon America. While the ALP governments of Curtin and Chifley sought to maintain and strengthen links with Britain, it was the Menzies administration that took the most decisive steps away towards this realignment. Economics was at the heart of this change.

There is broad acceptance that the dominant feature of Australian foreign policy in the decade after 1942 was a search for security.12 First the Japanese and then the apparent Communist threat had made the Far East and the Pacific a more dangerous region, at the same time as Australia’s traditional protector, Britain, proved less willing or able to help. But, while military strength and cultural links were significant, the core of Australia’s search for security was domestic economic development. Menzies explicitly explained Australian development in national security terms in his 1950 Anzac Day broadcast, “the best way in which Australians can guarantee a peaceful existence and guard against attack is by working hard for the development of Australia.”13 Australia’s post-war reconstruction was a critical factor pushing it towards the dominant United States and other Pacific Rim countries, notably Japan, and away from weaker Britain.

←6 | 7→This book shows how the changes caused by this focus on economic development impacted Australia’s international relationships. As Joan Beaumont argued, “foreign policy is something of a Cinderella in Australian historical writing.”14 Beaumont observes the domination “in recent decades by studies of race, gender, class and post-colonialism, all within a general preference for social history.” Therefore, perhaps it is not surprising that consideration of economics, Australia’s fundamental domestic transformations, and their consequences have been broadly absent in studies of its foreign policy. Economic history, post-2008, has started to regain importance globally, and even within Australia.15 Indeed, Kenneth Lipartito suggested that recently there “has been something of a cross-disciplinary convergence in economic history.”16 However, this has not occurred in studies of Australian foreign policy. Thomas Piketty described his study of tax returns as “a sort of academic no-man’s land, too historical for economists and too economistic for historians.”17 The no-man’s land between Australian economic and diplomatic history seems equally broad.

Details

- Pages

- XX, 292

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433181399

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433181405

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433181412

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433181429

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17510

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (April)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XX, 292 pp., 8 fig. b/w, 5 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG