Human Encounters

Introduction to Intercultural Communication

Summary

The volume also has a practical aspect. The author discusses subjects such as handling encounters with people using foreign languages; incorporating different life styles and world views; the use of interpreters, non-familiar bodylanguage; different understandings of time; relocation in new settings; the use of power and how to deal with cultural conflicts generally.

Published as a general textbook in English for the first time following a very successful original edition in Norwegian, also translated to Russian and French, this richly-illustrated book offers a refreshing and engaging introduction to intercultural understanding

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Foreword

- CHAPTER 1 Understanding in a Global World

- CHAPTER 2 Culture: Something We Have or Something We Do?

- CHAPTER 3 Communication Is Creating Something Together

- CHAPTER 4 Process Analysis: Building Bridges

- CHAPTER 5 Semiotic Analysis: Interpreting Signs

- CHAPTER 6 Hermeneutic Analysis: Understanding

- CHAPTER 7 Verbal Communication: Language

- CHAPTER 8 Nonverbal Communication: Body Language

- CHAPTER 9 Identity: Who Am I?

- CHAPTER 10 Context and Reality: Why Are They Doing This?

- CHAPTER 11 To Understand Oneself and Others

- Bibliography

- Index

Foreword

This book provides an introduction to intercultural communication and while it is intended for undergraduate students, it is useful for anyone seeking an overview of this rapidly developing field.

The field of intercultural communication may be helpful for studying international, national and domestic relations. But what does intercultural mean today? Cultures are constantly changing and cannot be summarized or defined as easily as before. Cultures cannot just be put into boxes and one of the consequences of globalization is that many previously recognized boundaries have little importance. Great mobility and technical inventions such as the internet have broken down obstacles of distance and have facilitated connections across the globe at an increasing speed. As a consequence, cultural, technical, economic and political mind-sets influence human encounters throughout the world. Communication does involve crossing borders, but which borders? In recent years, a new direction has developed within the field of intercultural communication called critical intercultural communication research (Holliday, Hyde and Kullman 2010; Nakayama and Halualani 2010; Piller 2011). As a result, researchers now place greater emphasis on the following points:

(a)Intercultural communication must be perceived in a critical historical context. It is not a discipline in itself, but other disciplines can shed light on the field: philosophy, psychology, religious studies, linguistics, sociology, social anthropology, information science and other sciences.

(b)All communication is in some way intercultural. Communication takes place between different parties who activate their unique intercultural frames of reference either domestically or internationally. Identity is a key word, but identity is dependent on the circumstances and on the interlocutors.

(c)The notion of culture in terms of national cultures must be critically scrutinized. All nations are influenced by different trends ←ix | x→and composed of different people who each relate to different cultural modes of interpretation.

(d)Culture cannot be reduced to an essence (core) or to something we have. Culture must be understood as much more dynamic, as something we do. Through acts of communication, we construct and reconstruct culture.

(e)Methodologically, more recent means of analysis have come into play. Examples include semiotics (the study of signs), hermeneutics (interpretation) and discourse analysis (the study of texts and social practices), not merely studying the process of communication.

(f)Power is central to the study of communication. It is a mayor challenge to map where the centres of power are situated in acts of communication.

In this book, I have discussed several of the challenges raised by the study of critical communication research, but I have not “tied myself to the mast”. Many of the points listed above can be discussed using different approaches. My attitude is that we need both the classical descriptive (essentialist) understanding of culture and the more modern dynamic (constructivist) approach.

The book has a European or even North-European point of departure. However, many cases are drawn from the rich international field and students from all over the world will benefit from the discussions included here. I maintain that the book is an introductory text and as such I have included well-known themes within the field like verbal and nonverbal communication, process analysis and the study of world views. Since European societies are increasingly becoming multicultural societies, I have also explored migratory processes, the construction of identity, the understanding of time, conflict management, and the use of power in communication. Underlying all these themes is the wish to understand and be understood.

The textbook is written for undergraduate students. It is intended that after studying this book the reader should, among other things,

•attain a broad knowledge of central themes, theories, issues, processes, tools and methods within the field;

←x | xi→•be able to apply academic knowledge and relevant research to practical and theoretical problems, as well as making analytic choices;

•be able to plan and accomplish varied tasks and projects, alone or as a participant in a group and in accordance with ethical requirements and guidelines.

This book intends to meet these requirements. My aim is to inspire students to adopt habits of self-reflection and engagement when facing the many intercultural challenges that exist today. The book challenges students to see people and contexts, not just in terms of academic and professional needs, but also in relation to their own ways of living. In order to assist students who wish to deepen their study of specific themes, I have included many citations of other works in addition to references to relevant literature in the field. When quoting from sources not written in English, I am responsible for these translations.

I have worked in this field for more than thirty years and in 1986 published the book Encounters between Cultures, the first of its kind in Norway, with a special emphasis on intercultural communication. Gradually, I became more convinced that cultures do not communicate, but people do. Cultures are abstractions; people are flesh and blood with aspirations, values, reflections, and emotions. When the book was reissued in 2001, and in 2013 in Norwegian, in 2016 in English, it was re-titled Human Encounters. I have retained the title for this new edition, though it is completely revised and rewritten compared to previous books, and one can find some of the same themes, illustrations, and models.

I wish to express my gratitude to my colleagues Tomas Sundnes Drønen, Kjetil Fretheim, and Marianne Skjortnes who published a Festschrift for my seventieth birthday titled Forståelses gylne øyeblikk (The Golden Moments of Understanding) and to the readers of the manuscript such as Iben Jensen, Stein Erik Ohna, Solveig Omland, Svein Strand, Diane Oatley, James Brian Oliver, and Ian Copestake who proofread the manuscript. My dear Marianne has shown patience seeing my back in front of the computer. Thank you for your encouragement and support. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the work of the publisher in realizing this project.

The author

Øyvind Dahl

The benevolent interpreter

CHAPTER 1

Understanding in a Global World

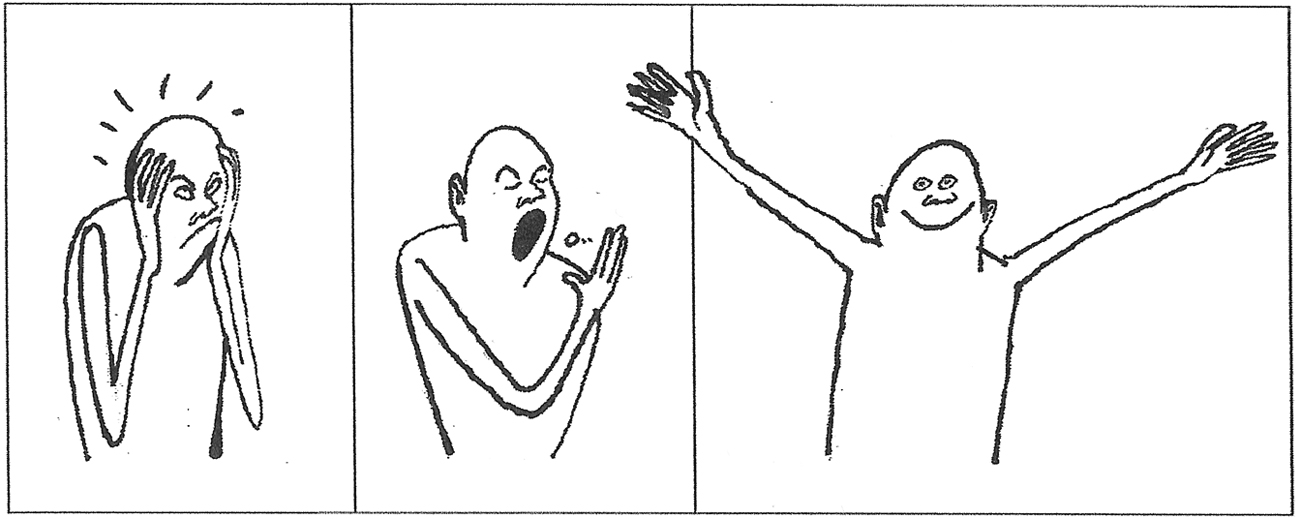

A pharmaceutical company wants to launch their brand of headache pills on the North African market, and the company marketing team was certain that the comic strip in Figure 1 would adequately communicate the effectiveness of the pills. The first image shows a man suffering from a headache. In the next, he takes the pills. In the final image he feels wonderful and no longer has a headache.

Figure 1The comic strip that caused a headache!

It seemed that the marketing scheme would have every reason to succeed and large posters were designed, printed and distributed. However, the company had forgotten one detail. The written culture was Arabic, a language that is read from right to left. And this also applies to comic strips!

This example illustrates how badly things can go when we have not taken the time to familiarize ourselves with how people with different cultural frames of reference interpret images and signs. It is also worth noting that such interpretation is usually carried out unconsciously. Those ←1 | 2→with an Arab perspective will automatically read from right to left, with the same immediacy that a European reader would read from left to right. Through our upbringing, education and training in a particular society, we are equipped with a number of assumptions and interpretive keys that we take for granted. As a rule we don’t think about them and thus use them on a daily basis to understand and make ourselves understood in our surroundings.

In this book we will focus on communication, how we understand and misunderstand one another, the types of preconceived expectations we have when we meet other people and how we acquire new understanding.

To understand and be understood

To understand each other and understand why we think and act as we do – even if one of us comes from Edinburgh, another from Istanbul, a third from Punjab in Pakistan and the fourth from Houston, Texas – has become more and more necessary. It is also important to see that cultures are not necessarily a matter of geographical distinctions. An electronics engineer from India and an electronics engineer from Scotland, who work for the same international company, have in many respects more in common than a lawyer from Delhi and a fisherman from Kerala State in India. But of course, the lawyer and the fisherman have many experiences in common, in that their children attend Indian schools, they pay taxes and speak Indian languages even though their languages are different − Hindi in Delhi and Malayalam in Kerala. In Norway a Malaysian immigrant may have difficulties understanding the Norwegian tradition of walking in the mountains. A Norwegian Malaysian spoke of how strange she found it that Norwegians seemed to enjoy working up a sweat and tiring themselves out while trekking in the mountains. In Malaysia “to go for a walk” meant walking through the city in one’s nicest clothes and meeting with people (Long 1992: 5, 13). An Irish pub in Berlin is not only full of Irishmen, but also attracts Germans.

Communication also has historical and social dimensions. Preschool children live in a world that is miles away from the environment in which ←2 | 3→their grandparents grew up. But it looks as if the grandchildren and grandparents “understand” each other superbly, nonetheless. Danish lower secondary schoolchildren with parents from Turkey or from Hirtshals also find a way of interacting which enables them to “understand” one another. What does it imply to understand and be understood? What do the different cultural frames of reference mean for intercultural communication?

Even when there are a great many differences, it often proves to be the case that most people can learn to understand each other. It is luckily not necessary to be the same in order to be able to communicate. When we meet other people who speak other languages, are of another religious faith and have other ways of doing things, we are also obliged to question our own ways of thinking and our own ways of doing things. This type of challenge is part of what is most fascinating about intercultural communication – a concept that is used when we compare ways of communicating across cultural divides.

Each and every true understanding is by nature oriented towards finding an acceptable interpretation of life phenomena. This can only occur through interaction between people. Understanding is created in a social setting, through dialogue and cooperation between people. Seeking understanding in a conversation implies an endeavour to find the most adequate terms to cover what you are trying to say. The better my interpretations coincide with your ideas, the better we understand each other. To understand is like when two wires suddenly acquire contact so sparks fly. “A-ha, now I understand what you mean, what your intention is!” Or: “Now we have both reached a new understanding. With the help of imagination and creativity we have actually established a new, mutual understanding – we are of the same mind regarding how this phenomenon is to be interpreted!” (For the time being, in that all standpoints can be changed or discarded in the next round …)

Details

- Pages

- XII, 298

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789979527

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789979732

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789979749

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789979756

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17491

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (March)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XII, 298 pp., 44 fig. col., 18 fig. b/w, 3 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG