A Hero for the Atomic Age

Thor Heyerdahl and the «Kon-Tiki» Expedition

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

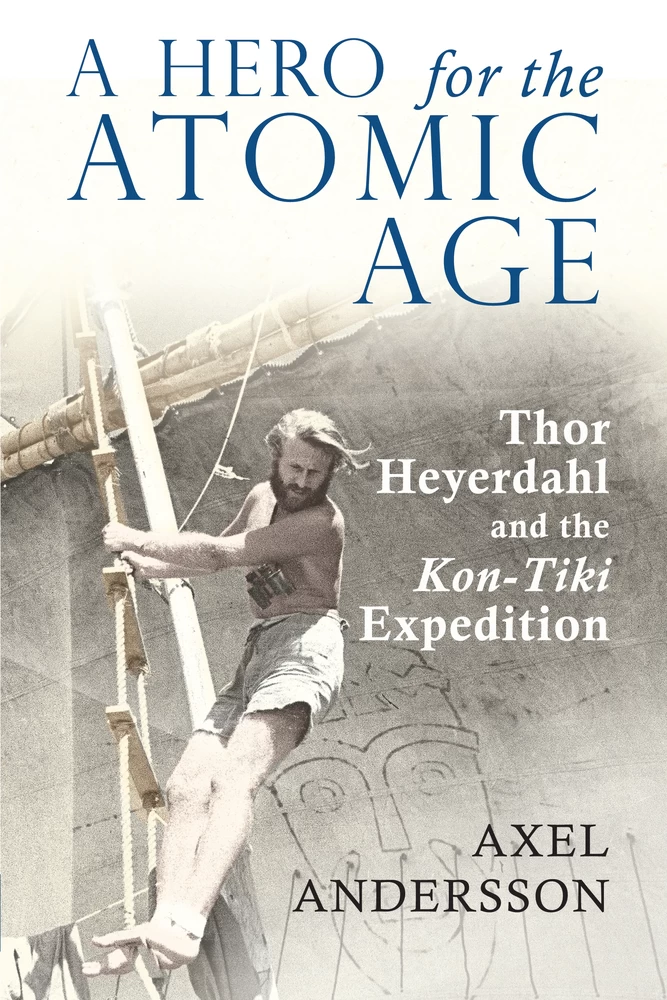

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Plates

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Preface to the Revised Edition

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Man and the Myth

- Chapter 2 Making the Kon-Tiki

- Chapter 3 From Raft to Brand

- Chapter 4 The Seamless Craft of Writing Legend

- Chapter 5 To Review a Classic

- Chapter 6 The Kon-Tiki Film and the Return to Realism

- Chapter 7 A Lone Hero of Adventurous Science

- Chapter 8 White Primitives and the Art of Being Exotic to Oneself

- Chapter 9 The New Postwar Sea and the Pacific Frontier

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Plates

The plates are located between pages 116 and 117.

1. Heyerdahl and his wife-to-be Liv Torp in the Norwegian mountains. © Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo

2. Heyerdahl and Liv Torp bathing in a river on Fatuiva. © Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo

3. King Heyerdahl of Fatuiva. © Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo

5. The crew of the Kon-Tiki. © Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo

6. The Kon-Tiki on the open seas. © Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo

7. Haugland and Raaby doing maintenance work on one of the four radio sets. © Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo

10. Hesselberg plays guitar for Raaby on the raft. © Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo

←vii | viii→13. Heyerdahl the scientist and Heyerdahl the adventurer. © Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation

Preface and Acknowledgements

We all need heroes and heroines, whether we treasure them secretly or propagandize publically on their behalf. Certain figures become larger than life because we crave for guides to lead us through complex realities. Culture creates heroes, not the other way round, but at some point it becomes impossible for those accorded heroic status to live up to our unreasonable expectations. The failed hero is as common as the redeeming one. Reality is always too multifaceted, too mercurial, for any guide to show the way. The figure that used to be larger than life now becomes associated with the meanest and pettiest of life’s attributes. This ancient mythological pattern has been speeded up to a dizzying tempo in the modern media environment with its cult of celebrity. The heroes and heroines of the twenty-first century experience the cruel destinies of mayflies. Years in mud, and then a day-long Icarus flight to soaring heights before being burnt by the sun.

I had a hero. His name was Thor Heyerdahl. The Norwegian experimental archaeologist who stunned the world with his 1947 KonTiki raft journey across the Pacific inspired me to dream of far-away adventures. It was Heyerdahl that made me dare to travel the world when I was old enough to leave the safe confines of home. Many years later I decided to study his life and writings in order to understand what kind of hero I, and so many like me, had made him become. I focused on his first major expedition, the Kon-Tiki, and tried to reconstruct how this eccentric voyage on a balsa-wood raft two years after the Second World War became a worldwide media sensation.

The first thing I learnt when studying Heyerdahl was that heroic legends are total systems. A hero cannot be believed ‘a little bit’, but must be admired as a whole. There were things about Heyerdahl and the ←ix | x→Kon-Tiki that were fantastic and worth celebrating like the creation of a new benign conception of the sea that he pioneered. There were also less appetizing aspects. That Heyerdahl the storyteller conscientiously created a narrative of his life was easy to forgive; most of us do the same. What was much more problematic was the jarring presence of a ‘white race’ in the Kon-Tiki story. Heyerdahl and his fellow Scandinavian expeditionaries came as young white men to South America and Polynesia and they sometimes behaved, as the saying goes, as children of their time. There was also another white race, Heyerdahl argued, a culture-bearing race of white teachers that had travelled the world in ancient times. It was their fabled voyage that Heyerdahl wanted to reconstruct. The idea of race, and of hierarchies of races, was contentious in the postwar period and remains so now. There is nothing innocent in the idea of a white race that had brought into being all the world’s great civilizations. It is a dangerous racist myth.

But this book is about more than Heyerdahl’s problematic white race; it tries to explain how heroes are made and how certain periods crave different adventures. I hope that it can be seen as both a celebration and a questioning of this process. It has however been with some remorse and sadness that I have tried to expose the different nuts and bolts of the legend. I know that it is easier to pick something apart than to put it together, and humbly take my bow in front of the storyteller Heyerdahl even though his theories were at times appalling. The time has now come to study the Heyerdahl legend. We need to understand how reality is, and was, far too intricate for a one-dimensional image of him to persist. This work has already begun in earnest in Norway where Roar Skolmen published a book criticizing Heyerdahl as a scholar in 2000 and in 2005 and 2008 Ragnar Kvam Jr published the first two of a probing three-volume biography that shed new and not always flattering light on Heyerdahl the private man. To these books can be added a loving parody on the KonTiki from 1999 by Erlend Loe entitled L. In contrast to these books my interest is in Heyerdahl as a modern hero and the Kon-Tiki as a media phenomenon. It is my hope that this focus will add another strand to the rendering of a more complex idea of Heyerdahl and his greatest adventure.

For those who wish to read the full Heyerdahl legend I would like to recommend Arnold Jacoby’s biography Señor Kon-Tiki, or Heyerdahl’s autobiographical text In the Footsteps of Adam, both available in English. For a description of the Kon-Tiki voyage nothing could ever rival Heyerdahl’s ←x | xi→own narration that is continuously being published in new editions. The Kon-Tiki museum in Oslo, which Heyerdahl helped create, also offers an exhibition about his theories and travels. It is here that the Kon-Tiki raft has its home, appropriately close to other remnants of Norwegian maritime history with their own museums such as the Gokstad Viking ship and Nansen and Amundsen’s Fram.

Writing this book has entailed a number of journeys for me, both physical and intellectual. Many have accompanied me and given me support along the way. I owe gratitude first and foremost to Victoria de Grazia, who supervised the dissertation out of which this work grew. Without her encouragement I would never have got up and walked so boldly. Thank you also to Bo Stråth, Aleksandra Djajic Horváth, Simon Toubeau, Clemens Maier-Wolthausen, Lucy Turner Voakes, Maria Graciela Lombardo and Siddhartha Della Santina who helped me so much with the dissertation, to Karine Grinde for the great times in Oslo and to my parents and sister for all their encouragement. That the Kon-Tiki Museum in Oslo granted me access to its archive proved invaluable for me, and special thanks go to Paul Wallin, who helped me get started with the sources. In Stockholm I was greatly assisted by Bodil Edvardsson at the Adam Helms Collection of Stockholm University Library. I also thank the Reading University Library, the Explorers Club in New York, Brooklyn Museum of Natural History and the Newberry Library in Chicago, as well as the Albert Bonniers Förlag Archive and the Swedish Film Institute Library in Stockholm for letting me study their archives. Even though I have been helped by many, any errors in this work are mine and mine alone. For those who desire a more comprehensive discussion on sources and literature please consult my dissertation ‘Kon-Tiki and the Postwar Journey of Discovery’ at the European University Institute in Florence.

This book and the dissertation on which it is based were written in Pian di Mugnone in Fiesole, Campo di Marte in Florence, Bercy, Le Marais and Île Saint Louis in Paris, Giudecca in Venice, Reitano on Sicily, King’s Parade in Cambridge, Gràcia in Barcelona, Wilmersdorf in Berlin, Pueyrredon in the Argentinean Córdoba and the small village of Bo in the Swedish forest. If only one could thank places; I owe so much to all of them. But I can at least end by thanking the one who walks by my side through a wondrous world; Tania Espinoza, precious companion.

Preface to the Revised Edition

History and myth relate to each other through missed encounters. The conversation is delayed, refracted and easily misunderstood. History talks of measurable time, myth about eternity; and they do it in different places. It is simple to argue that both causes are noble. They are also easily abused. However, a mutual respect between them is necessary, even though it is difficult to embrace a complementary relationship when difference always seems to be at the other’s expense. This book about the modern myth-making surrounding the Kon-Tiki expedition, first published seven years ago, is a testament to this.

Seven years changes little in the larger scope of the clash between history and myth. Elsewhere, the changes can be dramatic. This edition includes only minor revisions. I have taken the chance to correct some smaller errors, insert a few clarifications and add some new findings. The key objections to my work in Norway, where the reception was in part hostile, and beyond, had to do with a supposed anachronism that, according to my critics, led to me failing to see Thor Heyerdahl as a child of his times and, at the same time, being unable to see Heyerdahl in the light of his political activism of later years. Detailed discussions in the original text anticipated and responded to these accusations. If Heyerdahl is to be historicized in the post-war era of the Kon-Tiki, the most relevant context seems the colonial wars of liberation, not the nineteenth-century era exploration that he was himself nostalgically referring to. And to read Heyerdahl’s adventures in the late 1940s through the ones in the 1960s and beyond would be properly anachronistic. However, it is now impossible not to also understand this book, and these reactions to its first publication, through recent developments.

For all the racial and mythological undertones of Heyerdahl’s ‘science’, he was in many respects on the right track with his focus on the waterways ←xiii | xiv→as connectors of peoples and cultures. We have seen, since 2010, a rapid development in the West of barriers not only between the privileged and the unprivileged, but also between each other based on our opinions. Our world is becoming increasingly, and worryingly, insular, with real and metaphoric island-hopping soon a distant memory. The low-intensive Kulturkampf between radical and conservative, globalising and nationalist has escalated with both sides carrying much blame for the dialogues that wilfully never happened even though they were most urgently needed. Revisions of myths, especially nationally adopted myths, cannot avoid stepping right into the conflict zone. This war might have been simmering for a long time, but what a little while ago constituted a background has now come to the foreground.

A post-Marxist revisionist discourse imprecisely referred to as political correctness and identity politics has squandered easy rhetorical victories by hedging the bets too squarely, and too self-indulgently, on the weapons of the powerless: the power to negate, to pick apart without putting together again. Its ideological mirror has been at least equally reactionary when it has used the shrillness of its opposition to avoid any type of soul-searching or self-reflection. In the middle of this intellectual impasse, tens of thousands have died in seas like the Mediterranean, seeking a better life on much flimsier vessels than the Kon-Tiki. And other present planetary issues, like the environmental challenge that Heyerdahl would be so instrumental in bringing to light, are being foreclosed on a level that is nothing but staggering for any reasonable thinking mind.

A Hero for the Atomic Age: Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki Expedition sets out to revise a myth, and to understand the process of myth-making. Its undertaking was provocative for some seven years ago, and might be even more so now. The times are changing. Still, I have decided in large part to keep it as it was. Had I written it today, it might have looked somewhat different, but it is preferable that it retains the tone in which it was conceived. It was an endeavour to investigate, with the tools of the historian, a personal fascination that at one point, for its author as for many others, had been visceral and spellbinding; and, above all, inspiring. It retains the rawness of such an enterprise and it would do it a disservice to try to temper it.

To read and think about Thor Heyerdahl and the Kon-Tiki expedition in 2017 is, yet again, to be faced with the question of what we are dealing with above and beyond the foundation of a pseudoscientific theory of a ←xiv | xv→prehistoric white culture-bearing race with global reach. What can be retained after the media event has been deconstructed? Our times demand necessary concessions to myth. The adventure was for a long time the key component of this story for many, including an earlier version of myself as a child. But man-against-nature rings hollow in a world where it is man, ourselves, who has created the environmental problems that we are facing, now increasingly as existential threats. We have to look elsewhere.

The final chapter of this work is an exploration of Heyerdahl’s relationship to the sea. It is complicated by, and also implicated in, his migratory theories; but there I also tried to trace a relationship to the modern post-war ecological movement. It is here, it strikes me more than ever, that Thor Heyerdahl’s legacy takes on a positive and generative guise. It is also here that we can, and I do not venture to use such terms lightly, care for the heroic story and for Thor Heyerdahl’s relationship to myth. We need myths still, of course. We need the inspirational and the archetypical. There is also a need to challenge, rewrite and reject myths. The two go hand in hand, a little like remembering goes hand in hand with forgetting.

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 262

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788742757

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788742764

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788742771

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788742788

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781906165314

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13223

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (May)

- Keywords

- scientific dogmatism adventure exotic rebellion

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2018. XVI, 262 pp., 14 b/w ill., 1 fig.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG