Jotería Communication Studies

Narrating Theories of Resistance

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

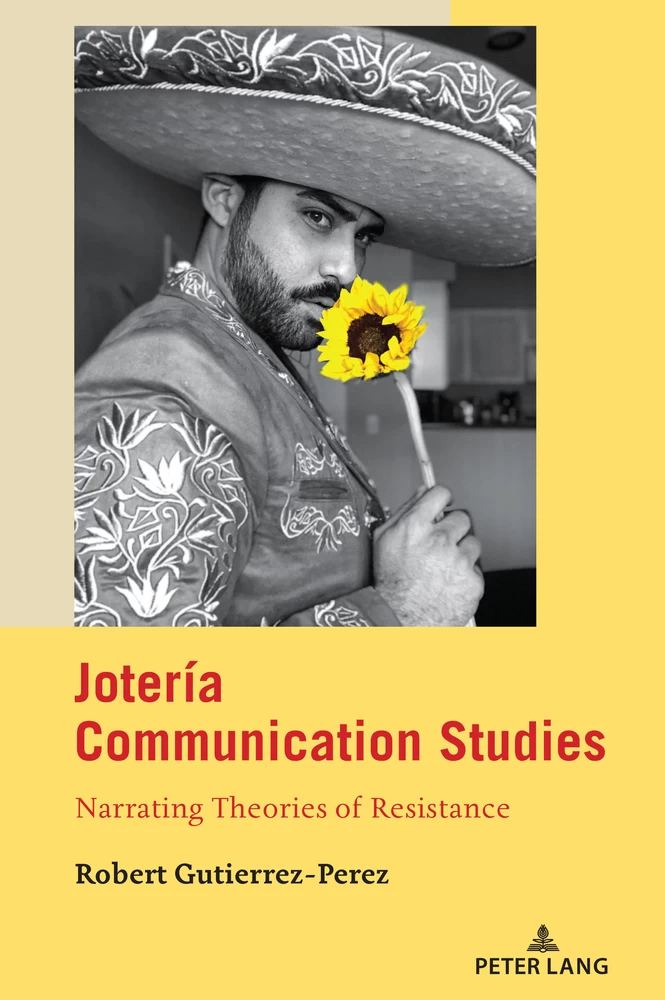

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Theories in the Flesh as Resistance in Everyday Communicative Life

- Part One: Borderlands Narratives and Snapshots of Jotería-Historias

- Remembering Jotería

- 1 Decolonizing Communication Studies—A Borderlands Lens to Narrative Theory

- 2 “I (Will) Always Watch You”—Remembering Loss, Spirituality, and Cultural Inheritance

- 3 Haunting Breath—A Testimonio (Talkback) of Desire and Belonging

- You Call Me Monster

- 4 Embracing Nepantla to Survive Intersectional Traumas of Higher Education

- Part Two: Narrating and Staging Theories and Methods of Resistance

- Unbecoming the Poem

- 5 Performance Auto/Ethnography—The Disruptive Ambiguities of Disidentification at “Latina Drag Night”

- 6 The Four Seasons of Oral History Performance, or Theories from the Fringes of Aztlán

- Part Three: Jotería Performance Rhetoric

- 7 Queer of Color Performances of Generational Dis/Continuities, Culture(s) of Silence, and the Labor(s) of Intelligibility

- I Put a Spell on You

- Back to Love / A Jotería Myth

- La Hambre

- Jotería Resistance

- The Lifeguard Station

- The Secret

- Welcoming the Shadow

- MUERTE DEL MACHO / Death of the Macho

- Conclusion: Interview with Robert Gutierrez-Perez by Luis M. Andrade

- Affirmations for the Jotería Community

- Another Sun Rises

- The Promise

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Acknowledgements

The task of acknowledging those who have made this work possible is difficult because I believe that reality is socially constructed and radically interconnected to everyone and everything, so I couldn’t be here without you (the reader) or without so many others in my life. However, I would like to acknowledge Gloria Anzaldúa as a guiding theoretical and philosophical light for me throughout my academic journey and this book. Thank you for your scholarship, activism, art, and life. You are a light in the dark for so many. Additionally, I am incredibly proud of my academic lineage and academic family. Thank you Bernadette Marie Calafell for your friendship, mentorship, and for being a fierce Chicana. You are a role model, and I am and will forever be part of the House of Calafell. With that said, I want to thank Haneen Al-Ghabra, Shadee Abdi, Miranda Olzman, Pavithra Prasad, Anthony Cuomo, Shinsuke Eguchi, Fatima Zahrae Chrifi Alaoui, Richard Jones Jr., Sophie Jones, Kathryn Hobson, Dawn Marie McIntosh, Raquel Moreira, and Sara Baugh for your support during this project. Thank you to Jessica Johnson, Nivea Castaneda, and Brendan Hughes! You three have saved me so many times. I love you. Lore LeMaster, Michael Tristano Jr., Cypress Amber Reign, Salma Shukri, Kate Willink, Lacey Stein, Jared Vasquez, Leandra Hernández, Amanda Martinez, Gust Yep, Jeffrey McCune Jr., and Godfried Asante, I will forever be grateful and appreciative of you. Kristen Foht ←ix | x→Huffman, thank you for your careful reading and suggestions of prior drafts of this book. You are amazing! Luis Manuel Andrade, mi esposo academico, te amo mucho. Also, right after graduation with my doctoral degree, two of the committee members from my dissertation passed away, but this book and my intellectual orientation to inquiry is forever informed by Roy Wood and Luis León. Luis, this book is especially for you. Thank you for every moment of your life that you gifted to me. Your mentorship, love, and faith in me led me here. Finally, I want to thank Deanna Fassett, Rona Halualani, Kathleen McConnell, Wenshu Lee, and David Terry for their mentorship and support during my undergraduate and master’s program. San José State University and the department of Communication Studies at this university empowered me to move beyond my poor and working-class roots through its commitment to an affordable, accessible, and excellent world-class education. I am forever indebted to this institution and to the city of San José.

On a more personal note, I want to thank my husband and best friend: Juan Carlos Perez. Our journey has only begun, and I am grateful and blessed to be able to witness your radiant and beautiful spirit in this life. As one of the 18,000 couples married before Proposition 8 passed in California, ours is one of the first queer unions acknowledged by law in the United States, and I will always cherish our queer marriage. Regardless of what form our union takes in the everyday, you are my angel, and indeed, I am the man I am because of your love, care, and commitment. I love you.

To my found family, I love you so much! Patricia Corrolla, Carlos Ramirez, Mark Cardiel, Francisco Clavel, Matthew Kopec, Kimberly Carrasco, and Melate Bekele Tolossa. To Luis Armendariz, thank you for being my muse throughout this project. When I saw you, I knew we were meant to meet, and you will always hold a special place in my heart. I wish you nothing but happiness, love, and Chicano soul. Further, I want to thank my wonderfully talented, intelligent, and social justice-engaged siblings that have become the core of what I know to be my roots. Thank you to my siblings and to my parents for always loving me just as I am. To Kevin, Derek, Tony, and Carly, I cherish each of you so much. Melissa Perez, you are the best sister-in-law that a guy could ask for, so thank you for your years of support and friendship. I would also like to thank my grandfather, Dwayne Weatherby, for being a wonderful father figure to me. Also, I want to thank my grandmother, Mary Weatherby; you are indeed a miracle and a blessing. I love and cherish you deeply and always. There are many others that have been part of this journey, and there may not be space to place all your names on this page or in this book, but please know that I love you. Thank you.

Introduction: Theories in the Flesh as Resistance in Everyday Communicative Life

There is something very powerful about a story. Once you tell a story or a narrative, it becomes alive, wild, and hungry.1 What traumas, secrets, and intimate wanderings will I feed to this story? What narratives of power and resistance can I share? If I refuse the process, then will this theory made from my flesh starve and die? It has taken me many years and decades to reach this moment in life. This location right here on the page where I am finally able to believe that my story or my theorizing is worthy—I am valid, I am enough, I matter. Gloria Anzaldúa, in Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro, describes theory as a story about the world, and as a story, it emerges out of a historical and political context.2 It is not a dead object as understood within the Western gaze, but rather, these theories (re)perform every time the images, symbols, and metaphors on the page are utilized in the everyday.3 For example, I envision you reading this somewhere—possibly for a class assignment, for a manuscript you are working on for publication, for inspiration for some poem, some song, some cultural artifact or performance in process—and hopefully, you are someone who has been searching for this book. The Black and Brown immigrant cook on the line making salads or washing dishes; the primo or sobrino that your gay tío or tía has been wanting to talk to you about something; or the Chicanx and Latinx LGBTQ everyday person riding the bus, working and chasing sueños, surviving, and sometimes thriving in ←1 | 2→their truths. Yes, the text is frozen on the page, but every word you read enacts, performs, and re-performs an “equipment for living.”4 The performativity of the utterance of a story moves through the everyday world of communicative behavior and shows how we can make meaning of our experiences of history, society, and culture.

For example, “joto” is a derogatory label used to discipline, describe, categorize, and hurt Jotería, as joto roughly translates as “faggot” or “queer.”5 As a homophobic slur in the Spanish language, joto is beginning to be reappropriated by Jotería as a “dramatic gesture toward resignifying the term and refuting the negative connotations that it has carried historically.”6 Like the Chicanos, Chicanas, and Chicanxs that came before them, Jotería draw on the myths, history, and politics of Aztlán and other Latinx or Mestizx cultures to challenge master narratives of invisibility and disempowerment, and this labor is undertaken within an intersectional, hegemonic system of control.7 Jotería studies emerged out of Chicana/o studies and “can be considered a critical site of inquiry that centers on nonheteronormative gender and sexuality as related to mestiza/o subjectivities.”8 Yet, Jotería studies is interdisciplinary because jotos and jotas have found spaces to survive and thrive across the disciplines, so this story of joto is complex, circular, and oftentimes, misunderstood and made monstrous.

Aye gente, I feel myself slipping into the academic training that compels me to cite more, explain deeper through complex vocabulary and complex sentences, and in general, separate myself from the masses by writing in a specialized language. Throughout this book, I’ve struggled to clearly articulate the theories of power and resistance that I have collected and analyzed through multiple communication research methods and methodological approaches. I want to show the rigor and validity of these methods and this scholarship with Jotería; yet, my audience for this book is not solely scholars and practitioners from communication studies, gender and sexuality studies, performance studies, cultural studies, or even, Latinx and Chicanx studies in education, sociology, history, literature, media, arts, and humanities. I envision this book to be the handbook that I never had. This book speaks to and with those nonheteronormative mestizas/os who perform their sexuality and gender in queer practices and queer communicative forms—Jotería. This book is for those Jotería and their allies who are creating spaces of survival within a system that wants them silenced, on the margins, and/or in their graves. How can I make it clear that in order for me to survive in the world of the everyday that I had to write this book? I needed you as my reader—desperately.

←2 | 3→Why Do You Want to Write This Book?

When I was an elementary school student, my mom and dad allowed me to buy a big thick book at la pulga called Greek Mythology by Edith Hamilton.9 For a young person sent to a private Christian preschool, kindergarten, and first grade in Milpitas, California, the stories reminded me of those we heard in the Bible readings that I experienced weekly and sometimes daily. In my mind, the stories of Athena, Artemis, Atlanta, Apollo, Zeus, Medusa, Venus y más played out on the same fabric board and in the same paper cutouts of my Bible-reading storytelling sessions. I took these stories and reimagined them. I constructed ←3 | 4→telenovelas for all my toys on the carpet or in the bathtub with my brother. My everyday communicative life became a place where I discovered I could escape by going on “flights of the imagination.” When I spent my recesses alone because I was separated out for my intelligence, I wove my cuentos. When I was reading my books while my primos played at the family reunion, I gathered more narratives to help me live my life.10 The point is that these mitos y leyendas awoke and were (re)performed by my body, and the way I did those stories was by doing them in particular ways, under particular circumstances, and toward a particular horizon. The historical and political context of these narratives place them into the public and private spheres, which becomes encoded into the culture and the society of a geographic location. And like water to fish, culture becomes the air we breathe, and these atmospheres of influence we inhabit become like Venn diagrams where we co-create culture and society endlessly in our co-constructed images. In the busyness of an ever-growing, interconnected, neoliberal capitalism and globalization, it is easy to forget the underground reservoir of images and symbols that flow, move, and bubble up from the subterranean spaces of shadow (the cave).11 These archetypical images, metaphors, and symbols continue to breathe through our breath; narratives are an everyday performance with performatives that can be observed and shared in the everyday acts of telling the told or through everyday communicative life.

Jotería Communication Studies

I specifically remember when I first felt shame for exhibiting my sexuality. I was sitting on a tall stool at the kitchen peninsula at my grandparent’s home in Milpitas.12 I was young, perhaps 3 or 5. I was rubbing my privates—to scratch or to adjust or to learn about the body I was inhabiting for the first time. My grandmother was aghast. She scorned me, “Don’t touch yourself! If you touch yourself, Jesus will make your hands fall off!” The image of two bloody stumps for hands revisits my mind sometimes when I masturbate or have sex with other men. Shame. In this micro moment, the story that was being communicated to me was: “Sex is bad. Sexuality is a sin.” Even to this day, my grandma earnestly approaches me to tell me that her only goal left in life is to make sure all her children and grandchildren will join her in heaven. The unstated assumption being that, currently, I will not be joining her. I am bad. I am a sin. In writing this book, I am not only conflicted with who you are as the reader/audience, but I’ve also struggled because writing this book means taking risks and being ←4 | 5→vulnerable, as I am in fact an imperfect person and scholar. It will mean telling secrets. Like Anzaldúa writes: “One of my biggest fears is that of betraying myself, of consuming myself with self-castigation, of not being able to unseat the guilt that has ridden on my back for years.”13 I want to shock the reader and myself shitless.14 In this book, I shake the foundations of my reality in the service of articulating the immense labor undertaken by people on the periphery of society and culture, and I am nervous because I will have to tell stories that I have never told before. Stories that my family, colleagues, community, and culture may not want me to tell—labeling me traitor, queer, unmentionable, untouchable, sinvergüenza—but I have to do the work, la tarea.15 I am compelled to write this book because there are too many of us that are forced into silence, into the margins, into death.16 I write because there are too few of us here in academia.17 I write because too many of us have lost our lives before our scholarship, art, and activism was complete. I write to heal myself and others traumatized and hurt by White supremacist, capitalist, cisheteropatriarchy.

Like the old adage goes, history is written by the victors. So, what of the marginalized? Do they not have a story about power, culture, and history worthy of (re)membering? Or, as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak asks, “Can the Subaltern speak?”18 The book currently in your hands is about how gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (GBTQ) Chicanos and Latinos generate theories of resistance to carve out spaces to live and sometimes thrive. The focus on GBTQ Chicanx interlocutors is not meant to ignore the histories, politics, narratives, cultural artifacts and productions, or experiences of the rest of the Jotería community; instead, it is an acknowledgement that the beauty, intellect, creativity, and bravery of our community cannot and should not be attempted to be encapsulated in its complete entirety within one single book. This does not mean this space isn’t for you or that I am not speaking with you.19 For example, the scholarship, theorizing, experiences, and cultural representations of women of color are critical to any understanding that this book on power, history, culture, communication, and resistance may offer to the reader. Further, given the radical interconnectedness of identity, culture, and power, the data that was collected itself points to, implicates, questions, gives insight into, and engages multiple communities, because GBTQ Chicanxs, like all interlocutors, form their identities in difference.20 That is, I am this because I am not that.

Communicating across difference, living in and with difference, embracing monstrosity, and narrating these experiences on the margins is a central focus of this book. Discussing identity negotiation, De Los Santos-Upton notes how identity construction is interpersonal, cultural, contextual, historical, and structural ←5 | 6→as identities are constructed in relationship to others.21 In other words, the process of identity construction is political because:

Details

- Pages

- X, 300

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433164583

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433164590

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433164606

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433164613

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433164620

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18436

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (September)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2021. X, 300 pp., 9 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG