Changes in Argument Structure

The Transitivizing Reaction Object Construction

Summary

"This is an unusually clear and empirically rich study which uses an overlooked construction in English to explore a broader development in the grammar and to engage with current trends in theoretical linguistics." Olaf Mikkelsen (University of Paris 8) in Nexus-AEDEAN 22/2 (2022): 88.

"This is a thought-provoking and empirically rich study, which sheds new light on an overlooked construction and its history. One gets the sense that few stones have been left unturned in Bouso’s work on the ROC. The review of the existing literature on the construction is very comprehensive, and the book contains more than 450 numbered examples in total, so it may be used both as a bibliography of earlier work and a handy data source for other scholars interested in the ROC. […] One very attractive aspect of the book is that it paves the way for future studies in numerous respects." Sune Gregersen (Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, U. de Copenhagen) in Research in Corpus Linguistics 10/1 (2022): 197-201.

"The monograph 'Changes in Argument Structure' is a well-documented, rigorous study that will be enjoyed by both experts and novice researchers interested in the history of the English reaction object construction. The strengths of the book are the originality of an uncharted area in historical linguistics, the exploration and comparison of the development of the ROC in two varieties of English, namely British and American, the parallelism between the ROC and other constructions of the English language, such as the way-construction, and the use of a complex methodological perspective (e.g. collexeme analysis as well as several statistical tests)." Andreea Rosca (Universitat de València) in Miscelánea: A Journal of English and American Studies 69 (2024): 245-248.

"The study clearly achieves its goal of providing a meticulous and convincing application of by now rather standard concepts in Construction Grammar to a particular, to-date unexplored phenomenon. (...)". It "constitutes a great contribution to the growing body of (diachronic) Construction Grammar, and a model illustration of how constructionist thinking can be used for the characterisation and tracking of peculiar but thought provoking linguistic patterns." Eva Zehentner (University of Zurich) in English Language and Linguistics (2025): 1-7; Published online by Cambridge University Press.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1 Aims and scope

- 1.2 Research questions and hypotheses

- 1.3 Overview of the following chapters

- PART I Transitivization, Reaction Objects and Construction Grammar

- 2. The process of transitivization in the history of English

- 2.1 Old and Modern English valency

- 2.2 The rise of double-functioned or amphibious verbs

- 2.3 Causes of the process of transitivization: Visser’s proposal

- 2.3.1 Loss of OE transitivizing/causativizing affixes (be-, ge-, Gmc -j/-i)

- 2.3.1.1 The prefix be- (Marchand 1969)

- 2.3.1.2 The prefix ge- (Lindemann 1970)

- 2.3.1.3 The Germanic suffix *-(i)ja- (García García 2012)

- 2.3.2 Inflectional syncretism followed by reanalysis of the dative/genitive complement

- 2.3.3 Twofold interpretation of be + past participle: Perfect and passive

- 2.3.4 Changes in the complementation patterns of intransitive verbs normally construed with a prepositional object

- 2.3.5 Use of verbs expressing human and animal sounds and other verbs such as smirk , smile and persist as if they were synonyms of say

- 2.4 Summary

- 3. Reaction objects: Review of the literature

- 3.1 The object in descriptive reference grammars

- 3.1.1 Historical grammars

- 3.1.1.1 Otto Jespersen (1909–1949)

- 3.1.1.2 F. Th. Visser (1963–1973)

- 3.1.2 Contemporary grammars

- 3.1.2.1 Quirk et al. (1985)

- 3.1.2.2 Huddleston and Pullum et al. (2002)

- 3.1.3 Interim summary

- 3.2 Reaction object constructions and other related object types

- 3.2.1 Nonprototypical objects

- 3.2.1.1 Cognate objects

- 3.2.1.2 Way- objects

- 3.2.1.3 Reaction objects

- 3.2.2 Concluding remarks

- 4. Construction Grammar: Synchronic and diachronic perspectives

- 4.1 Cognitive Linguistics and Construction Grammar

- 4.2 The origins of Construction Grammar

- 4.2.1 From idioms to Construction Grammar

- 4.3 Construction grammars: Common grounds

- 4.3.1 Grammatical constructions

- 4.3.2 Surface generalizations

- 4.3.3 A network of constructions

- 4.3.4 Crosslinguistic variability and generalization

- 4.3.5 Usage-based

- 4.4 Construction Grammar and language change

- 4.4.1 Defining constructional change

- 4.4.2 Dynamic network of constructions: Links, gains, losses and reconfigurations

- 4.5 Concluding remarks

- PART II Hands-On with Data: A Usage-Based Approach to the History of the ROC

- 5. The formation of ROCs

- 5.1 Characterization of the ROC

- 5.1.1 The modern reaction object construction: An overview

- 5.1.2 The reaction object construction in the network of English constructions

- 5.2 On the emergence of the ROC

- 5.2.1 Data sources

- 5.2.1.1 Jespersen (1909–1949)

- 5.2.1.2 Visser (1963–1973)

- 5.2.1.3 Levin (1993)

- 5.2.2 Methodology

- 5.2.3 Results

- 5.2.3.1 The ROC and the cognate object construction

- 5.2.3.2 The ROC and the way- construction

- 5.2.3.3 The ROC and the dummy it object construction

- 5.2.4 Concluding remarks

- 6. Development of the ROC in British English

- 6.1 Data sources and methodology

- 6.2 Frequency of occurrence and prototypical verbs in the construction

- 6.2.1 A collexeme analysis of ROCs: Identifying typical verbs in the construction

- 6.2.1.1 Some methodological considerations

- 6.2.1.2 Results and discussion

- 6.2.1.3 Summary

- 6.3 Distribution and function

- 6.3.1 Distribution of reaction objects across verb classes

- 6.3.1.1 Verbs of manner of speaking

- 6.3.1.2 Verbs of nonverbal communication

- 6.3.1.2.1 The verb smile

- 6.3.1.2.2 The verb nod

- 6.3.1.2.3 The verbs wave , frown , snort and wink

- 6.3.1.2.4 The verbs sigh , sob , weep , grin and laugh

- 6.3.1.2.5 Structural variation with nod and wave

- 6.3.2 Diachronic distribution

- 6.3.3 Textual distribution

- 6.3.3.1 Drama

- 6.3.3.2 Narrative fiction

- 6.3.4 Concluding remarks

- 7. Development of the ROC in American English

- 7.1 Data sources and methodology

- 7.2 Frequency and distribution

- 7.3 Productivity of the ROC and the way- construction

- 8. Summary and conclusion

- 8.1 The reaction object construction

- 8.2 Summary of the book

- 8.3 Writing the history of the ROC: A proposal of when, how and why the ROC develops

- 8.4 Theoretical implications and suggestions for further research

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Summary

- List of References

- Author’s Bio

- Series index

List of Abbreviations

agt |

Agent |

B&T |

Bosworth & Toller’s An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary |

BNC |

British National Corpus |

CLMET |

Corpus of Late Modern English Texts |

CLMET3.0 |

Corpus of Late Modern English Texts, version 3.0 |

CLMET-EV |

Corpus of Late Modern English Texts (extended version) |

COC(s) |

Cognate object construction(s) |

COCA |

Corpus of Contemporary American English |

COHA |

Corpus of Historical American English |

DAT |

Dative |

DIR |

Directional |

DNC |

Definite null complement |

DOE Web Corpus |

Dictionary of Old English Web Corpus |

EEBO |

Early English Books Online |

EModE |

Early Modern English |

EOC |

Expressive Object Construction |

Exp |

Experiencer |

Gmc |

Germanic |

HC |

Helsinki Corpus of English Texts |

HTOED |

Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary |

i |

Coreferentiality |

INC |

Indefinite null complement |

LME |

|

LModE |

Late Modern English |

ME |

Middle English |

MED |

Middle English Dictionary |

ModE |

Modern English |

N |

Noun |

NOM |

Nominative |

NP |

Noun phrase |

NV |

Deverbal noun |

OBJ |

Object |

OBJ1 |

Object 1 (indirect object) |

OBJ2 |

Object 2 |

OBL |

Oblique |

OE |

Old English |

OED |

Oxford English Dictionary |

P N construction |

Preposition noun construction |

pat |

Patient |

PDE |

Present Day English |

PC |

Predicative complement |

POSS |

Possessive |

PP |

Prepositional phrase |

PPCEME |

Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Early Modern English |

PPCMBE |

Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Modern British English |

PPCME2 |

Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English |

PRED |

Predicator |

R |

Relation |

REC |

Recipient |

RO(s) |

Reaction object(s) |

ROC(s) |

Reaction object construction(s) |

SEM/Sem |

|

sent. agt. |

Sentient agent |

SUBJ |

Subject |

Subsch. |

Subschema |

Syn |

Syntax |

(In)tr. |

(In)transitive |

VINTR |

Intransitive verb |

X, Y, Z |

Variables |

YCOE |

York-Toronto-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose |

1.Introduction

1.1Aims and scope

This monograph is concerned with the characterization and diachronic development of the so-called English reaction object construction (ROC; Levin 1993, 97–98), as in She mumbled her adoration and The door jingled a welcome. The ROC consists of an intransitive verb (mumble, jingle) followed by a nonsubcategorized object that expresses a reaction or an attitude of some kind (adoration, welcome), such that the whole syntactic unit acquires the overall extended meaning “express, communicate, signal X by V-ing”, that is, ‘She expressed, communicated her adoration by mumbling’ and ‘The door expressed, signalled a welcome by jingling’ in the examples above. In the terminology of Construction Grammar (Goldberg 1995, 2006, 2019), the theoretical framework adopted here, the ROC is defined as a valency-increasing argument structure construction, that is, an argument structure construction that contributes an extra argument (her adoration and a welcome in the examples above) to the event structure of the intransitive verb it blends with. In this respect, the ROC can be aligned with other constructions which also show a similar process of argument augmentation such as the causative property resultative construction (He wiped the table clean; Broccias 2008, 27), the cognate object construction (The hart lept a great leap; Visser 1963–1973: I, § 424 (b): 416) and the way-construction (She giggled her way up the stairs; Israel 1996, 218).

The three constructions just mentioned have been extensively studied over the last decades, mostly from a synchronic perspective (Jones 1988, Jackendoff 1990, Massam 1990, Goldberg 1995, Boas 2003, Goldberg and Jackendoff 2004, Höche 2009, Horrocks and Stavrou 2010, to mention just a few), but also from a diachronic viewpoint (Israel 1996, Broccias 2008, Mondorf 2011, Traugott and Trousdale 2013, Lavidas 2018, Perek 2018), an interest which is partly due to the emergence ←15 | 16→of Construction Grammar and to its application to language change (Lakoff 1987, Fillmore, Kay, and O’Connor 1988, Goldberg 1995, 2006, Hilpert 2013, Traugott and Trousdale 2013). By contrast, ROCs have so far eluded systematic investigation. The few linguists who have dealt with them have mainly focused on (i) the nonprototypical features of reaction objects in relation to other nonsubcategorized objects such as cognate objects and way-objects (Martínez-Vázquez 1998, Felser and Wanner 2001, Mateu 2001, 2014, Mirto 2007, 2012, 2017, Kogusuri 2009b, 2011, Bouso 2014a), and (ii) the characterization, the frequency and context of occurrence of the ROC in PDE and Spanish (Martínez-Vázquez 2010, 2014a, 2014b, 2015, 2016, 2017, Bouso 2012). If synchronic studies on the ROC are scarce, historical studies devoted to its diachronic development are non-existent. This monograph aims to fill this gap by offering a detailed characterization of the modern ROC from a Construction Grammar perspective and by addressing key historical issues such as when the ROC emerges, how it develops over time, and what mechanisms of change and factors may have propelled its development. These are considered to be the main contributions of this book, which hopes to raise questions and avenues for future research on the ROC from either a synchronic or a diachronic perspective.

My study on the ROC is in line with other diachronic studies on English verbs’ argument structure, a field of research which has attracted much scholarly attention of late. The areas which have been explored include (a) processes of argument remapping where there is a reorganizacion of the argument structure of a verb, (b) processes of argument reduction that imply the demotion or suppresion of one of its arguments, and (c) processes of argument augmentation where an extra argument is added, as in the case of the valency-increasing argument structure constructions mentioned above.

For the purposes of explanation, I will briefly discuss each of these processes in turn. I will first show a clear case of argument remapping based on van Gelderen (2014), then some examples of argument reduction, these based on Möhlig and Klages (2002), and finally, before heading into the research questions and hypotheses (§ 1.2), I will touch upon some general synchronic and diachronic features of the three types of valency-increasing constructions previously mentioned: the causative property resultative construction (e.g. He wiped the table clean), the ←16 | 17→cognate object construction (e.g. The hart lept a great leap) and the way-construction (e.g. She giggled her way up the stairs).

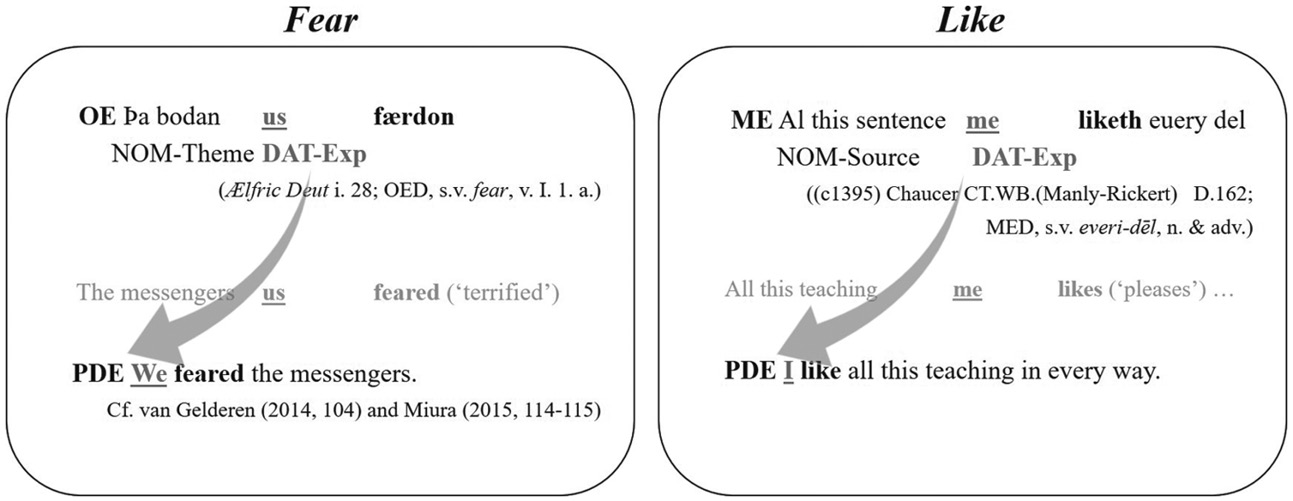

In processes of argument structure remapping there is a reorganization of the original argument structure of the verb. A clear example of one such process can be observed in the history of some psych-verbs such as fear (< OE fǽran ‘to terrify, frighten’) and like (< OE (ge-)lícian ‘please’), which possessed a different argument structure in earlier stages of English. Psych-verbs, or experiencer verbs, are those that “express mental states and involve the inclusion of an experiencer argument” which may act like the subject or the object of the sentence (van Gelderen 2014, 100).1 For instance, the psych-verb fear occurs with a subject experiencer (example (1)), whereas the psych-verb frighten takes an object experiencer, as shown in example (2).

(1)He fears that alien.

(2)That alien frightens him.

As explained by van Gelderen (2014, 104), many of the verbs that are now psych-verbs have become so recently (e.g. worry and thrill), a few subject experiencer verbs have remained stable over time – dread, hate and love were already in use in Old English (OE) with basically the same semantic structure – , while some originally object experiencer verbs such as fear and like have been reanalysed as subject experiencers over the course of history. This is illustrated in Fig. 1.1.

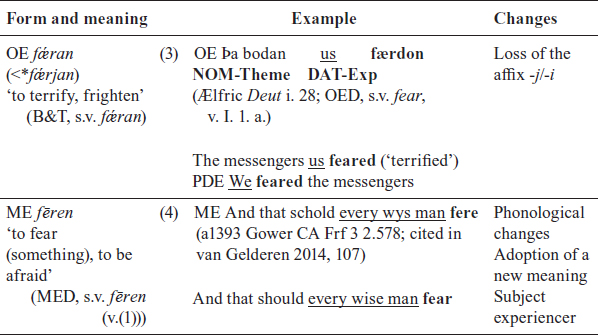

One possible cause of argument structure remapping is the loss of the morphologically overt causative affix -j/-i. This explanation fits well with the history of fear summarized here in Tab. 1.1. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the origins of fear (< OE fǽran) lie in the causative verb *fǽrjan (‘to terrify, frighten’) which had the Germanic causative affix -j/-i. During ME, OE fǽran phonologically developed into fēren, and acquired the meaning ‘to fear (something), to be afraid’ where the object experiencer argument becomes the subject of the sentence (example (4) in Tab. 1.1). This remapped argument structure is the one that fear shows in Present Day English (PDE), whereas ←17 | 18→the object experiencer pattern is now expressed by the verb frighten, formed by means of the noun fright (‘fear’) and the causative affix -en (e.g. The alien frightens me).

Fig. 1.1:Fear and like as examples of argument remapping

Moving now onto processes of argument structure reduction, commonly referred to outside Construction Grammar as detransitivization processes, these imply the suppression of one of the arguments of the event structure of the verb. Clear examples of this type of process have been described in Möhlig and Klages (2002), who deal with ←18 | 19→coreferential intransitive uses, generic uses, ergative uses and middle uses of a number of originally transitive verbs.

Tab. 1.1:History of the psych-verb fear: From ‘terrify’ to ‘fear’. Adapted from van Gelderen (2014)

Coreferential intransitive uses developed through a stage where they showed coreferential reflexive pronouns (e.g. John washed the clothes > John washed himself > John washed Ø). This example of detransitivization is mainly restricted to verbs belonging to the lexical domain of body-care or directed body-movement such as wash, shave, dress and move, which require an animate agent. Although the loss of –self reflexives does not seem to be tied to any specific historical period, Görlach (1999, 78) pointed out that “[m]any grammarians have noted an increase” in coreferential intransitive uses in the nineteenth century alongside other processes of transitivization (i.e. argument augmentation) and detransitivization (i.e. argument reduction). Interestingly, Jespersen (1909–1949: III, § 16.2: 325–331) also noted that the omission of the “cumbersome self-pronoun whenever no ambiguity is to be feared” is characteristic of Modern English (ModE) and more recently, Rohdenburg (2009) has taken Jespersen’s argument one step further and demonstrated that the suppression of overtly reflexive uses continues to the present day, with American English clearly leading the way.2 Interestingly, the reverse process, that of argument augmentation (i.e. transitivization), has been identified with ‘non-argument reflexives’, that is, with structures where reflexives do not express the referential identity of two participants (Siemund 2014, 52). Examples of these uses are shown in (5), where these ‘obligatory reflexive verbs’ cannot occur without the reflexive pronoun (see (6)), the pronoun itself cannot be coordinated with a full noun phrase (NP) (see example in (7)), nor can it be replaced by another NP (see (8)). As demonstrated by Siemund (2014, 70), the use of these non-argument reflexives has increased since ME times and they are probably still on the rise.

(5)absent oneself, content oneself, ingratiate oneself, perjure oneself, pride oneself, etc.

(6)John absented *(himself) from the meeting.

←19 | 20→(7)John absented *himself and his colleague.

(8)John absented *his colleague from the meeting.

(Siemund 2014, 52)

Like coreferential intransitive uses, generic uses of transitive verbs also represent a case of argument reduction. These refer to intransitive verbal uses where the object is implied by the cultural context (e.g. world knowledge), as shown in the Old and Modern English examples (9)-(12) for the transitive verbs read, drink, wash and drive.

Details

- Pages

- 392

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034340953

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034342650

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034342667

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034342674

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17960

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (June)

- Keywords

- reaction object construction corpus Linguistics intransitives

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 392 pp., 41 fig. b/w, 67 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG