Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Foreword to the English Edition

- Foreword to the Russian Edition

- Chapter 1 Introduction to Political Geography

- This course is an introduction to the study of political science, international relations and area studies, providing a systemic approach to the spatial dimension of political processes at all levels. It covers their basic elements, including states, supranational unions, geopolitical systems, regions, borders, capitals, dependent, and internationally administered territories. Political geography develops fundamental theoretical approaches that give insight into the peculiarities of foreign and domestic policies. The ability to use spatial analysis techniques allows determining patterns and regularities of political phenomena both at the global and the regional and local levels.

- § 2. Levels of Spatial Organization

- § 3. Principles of Spatial Organization

- § 4. Elements of Spatial Organization

- § 5. Research Methods in Political Geography

- § 6. Field Research in Political Geography

- § 7. Subdisciplines of Political Geography

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 1

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 2 Global Geopolitical Systems

- § 8. Geopolitics

- § 9. Globalization

- § 10. Geopolitical Systems

- § 11. Binary Geopolitical Systems

- § 12. Ternary Geopolitical Systems

- § 13. Heartland, Lenaland, and Rimland

- § 14. Polar Geopolitical Systems

- § 15. Great and Regional Powers

- § 16. Civilizations

- § 17. Macroregions and Continents

- § 18. Transcontinental Macroregions

- § 19 Transcontinental Countries

- § 20 Mesoregions of Europe

- § 21 Mesoregions of Asia

- § 22 Mesoregions of Africa

- § 23. Mesoregions of America

- § 24. Mesoregions of Australia and Oceania

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 2

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 3 Integration Groups

- § 25. Integration

- § 26. Integration Theories

- § 27. Regional Intergovernmental Organizations

- § 28. Cross-Border Regions

- § 29. International Transport Corridors

- § 30. Visa-Free Zones

- § 31. Preferential Trade Areas

- § 32. Free Trade Zones

- § 33. Customs Unions

- § 34. Common Markets

- § 35. Economic Unions

- § 36. Currency Unions

- § 37. Military Alliances

- § 38. Incorporating Unions

- § 39. Confederal Unions

- § 40. Integration Systems

- § 41. Mesoregionalism

- § 42. Transregionalism

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 3

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 4 States

- § 43. Statism

- § 44. Emergence of Statehood

- § 45. Evolution of Statehood

- § 46. City-States

- § 47. Empires

- § 48. Terms for Different States

- § 49. Forms of Government

- § 50. Nation-States

- § 51. State-Building

- § 52. Pan-National States

- § 53. Multinational States

- § 54. Divided States

- § 55. Stateless Nations

- § 56. Sovereign States

- § 57. Territory and Sovereignty

- § 58. Stateness

- § 59. Jurisdictional States

- § 60. Failed States

- § 61. Governments in Exile

- § 62. States with Limited Recognition

- § 63. Unrecognized States

- § 64. Insurgent States

- § 65. Proto-States

- § 66. Quasi-States

- § 67. Vexillology

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 4

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 5 Properties of State’s Territory

- § 68. Political and Geographical Position

- § 69. Geopolitical Code

- § 70. Size of State

- § 71. Shape of State

- § 72. Neighboring States

- § 73. Landlocked States

- § 74. Island States

- § 75. Enclaves and Exclaves

- § 76. Corridors

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 5

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 6 Composition of State Territory

- § 77. Land Space

- § 78. Maritime Space

- § 79. Airspace

- § 80. Subsurface Space

- § 81. Contiguous Zone

- § 82. Exclusive Economic Zone

- § 83. Continental Shelf

- § 84. Enclosed Seas

- § 85. Territorial Leases

- § 86. Occupied Territories

- § 87. Extraterritoriality

- § 88. Territories with Special Status

- § 89. Geopolitical Field

- § 90. Territorial Changes

- § 91. Disintegration and Partition

- § 92. Cession, Secession, Irredenta, and Annexation

- § 93. Territorial Adjudication, Retorsion, and Reprisal

- § 94. Marine Accretion, Regression, and Transgression

- § 95. Acquisition and Exchange

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 6

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 7 International and Internationalized Entities

- § 96. High Seas

- § 97. International Seabed Area

- § 98. International Airspace

- § 99. Outer Space and Celestial Bodies

- § 100. Arctic

- § 101. Antarctica

- § 102. International Straits

- § 103. International Maritime Canals

- § 104. International Rivers and Lakes

- § 105. Buffer Zones

- § 106. Transitional Administrations

- § 107. Free Territories

- § 108. Terra Nullius

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 7

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 8 Dependent Territories

- § 109. Expansion and Succession

- § 110. Discovery Doctrine

- § 111. Metropolises

- § 112. External Colonization

- § 113. Internal Colonization

- § 114. Colonialism

- § 115. Imperialism

- § 116. Decolonization

- § 117. Neocolonialism

- § 118. Postcolonialism

- § 119. Missions and Reductions

- § 120. Trading Posts

- § 121. Plantations

- § 122. Chartered Companies

- § 123. Crown Dependencies

- § 124. Mandates

- § 125. Trust Territories

- § 126. Non-Self-Governing Territories

- § 127. Unincorporated Unorganized Territories

- § 128. Incorporated Unorganized Territories

- § 129. Unincorporated Organized Territories

- § 130. Incorporated Organized Territories

- § 131. Bantustans and Reservations

- § 132. Condominiums

- § 133. Suzerainty

- § 134. Exarchates

- § 135. Dominions

- § 136. Princely States

- § 137. Tributary and Vassal States

- § 138. Puppet States

- § 139. Associated States

- § 140. Protectorates and Satellite States

- § 141. Limitrophe States

- § 142. Spheres of Influence

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 8

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 9 Capitals and Centers

- § 143. Geographical Center

- § 144. Pole of Inaccessibility

- § 145. Zipf’s Law

- § 146. Capitals

- § 147. Multicapital States

- § 148. Quasicapitals

- § 149. Coefficient of Metropolitanism

- § 150. Hypertrophy and Hypotrophy of Capitals

- § 151. Classification of Capitals

- § 152. Capital Relocation

- § 153. World Capitals

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 9

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 10 Borders and Cleavages

- § 154. Cleavages

- § 155. Limology

- § 156. Boundary Delimitation and Demarcation

- § 157. Limes, Limitrophes, and Frontiers

- § 158. Demarcation Lines

- § 159. Border Junctions

- § 160. Separation Barriers

- § 161. Divided Cities

- § 162. Electoral Geography

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 10

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 11 Regions and Municipalities

- § 163. Administrative Division

- § 164. Administrative Divisions and Autonomies

- § 165. Unitarism and Federalism

- § 166. Unitary States

- § 167. Federations

- § 168. Sovereign Regions

- § 169. Monarchical Regions

- § 170. Federal Territories

- § 171. Directly Administered Cities

- § 172. Capital Territories

- § 173. Regions with Multiple Subordination

- § 174. Extraterritorial Regions

- § 175. Supraregional Associations

- § 176. Subregional Entities

- § 177. Subregional Atonomies and Federations

- § 178. Municipalities

- § 179. Unincorporated Territories

- § 180. Communes

- § 181. Urban Regimes

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 11

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- Chapter 12 Spatial Identity

- § 182. Territoriality and Spatiality

- § 183. Absolute and Relative Space

- § 184. Heterotopias and Spatial Inversion

- § 185. Spatial Experience and Commemorative Places

- § 186. Spatial Myths and Co-Spatiality

- § 187. Territorial and Spatial Identity

- § 188. Place-Based Policy and Place Branding

- Key Terms and Concepts from Chapter 12

- Questions for Discussion

- Suggested Reading

- List of Political and Geographical Names to Be Memorized

- List of Common Political and Geographical Abbreviations

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Index

Foreword to the English Edition

It is a pleasure to introduce Dr. Igor Okunev’s comprehensive pathbreaking textbook contributing to the dynamic subject area of geopolitics merging the fields of political geography and international relations. The book is designed to introduce students to a broad range of subject matter relevant to contemporary international relations and political geography concentrating analysis on the spatial to political processes. There is no question that students of western nations will benefit through enhancing understanding of international relations, political science, and political geography by seeking to incorporate perspectives of non-Western experts in courses and research. This textbook, offered by a leading scholar among the younger generation of Russia’s academic community, will provide insight into the diverse methods for understanding and analyzing the complex interplay between geography and contemporary international political processes.

Igor Okunev and I have had many opportunities to collaborate with scholars throughout the world over the past several years while serving on the Executive Board of the Geopolitics Research Committee of the International Political Science Association. Igor’s efforts have been instrumental in advancing research in the areas of international geopolitics and political geography among the academic community within Russia and beyond. Igor’s research agenda has been highly valued by his colleagues offering support for the establishment of the Center for Spatial Analysis in International Relations under his direction at Russia’s premier diplomatic and foreign affairs university, Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO).

This textbook was developed in working with students in Igor’s courses offered in both Russian and English at MGIMO. Igor and I have co-chaired several videoconference sessions for students of Russia and the United States to explore international relations topic areas to include discussion of several of the topics covered in this textbook. Students from both countries consistently leave these joint seminars asking when the next meeting opportunity will occur, recognizing the critical value ←15 | 16→of having exposure to the worldviews, thinking, and methods forming the basis for the study of international political processes in other nations. The content introduced in Igor Okunev’s “Political Geography” is organized and structured to support easy integration into a diversity of courses in international relations, international security, political geography, and geopolitics.

This textbook should serve as an invaluable resource for assisting students developing the tools to better understand geographic variables in unraveling the sources of critical 21st century geopolitical challenges and opportunities to include regional conflicts, resource wars, great power rivalry and cooperation, and much more.

Sharyl CROSS, PhD

Director of the Kozmetsky Center of Excellence and Distinguished

Professor of International Relations, St. Edward’s University, Austin, USA

Former US Fulbright Scholar, Visiting Professor of International

Relations, Moscow State Institute of International Relations

(MGIMO University)

Foreword to the Russian Edition

I am excited to welcome Igor Okunev’s textbook on political geography. Igor is my younger colleague, whom I had pleasure to teach while he was a student. I have also supervised his dissertation on the community of island polities of Oceania. Igor is an exceptional personality having two great character traits that very seldom come together in one person. He has a very far-reaching mind able of sweeping vision and huge scrutiny. But at the same time, he is very keen about even minor details and particulars. He fashioned a comprehensive approach to political geography as a science and shaped it into a system of fundamental concepts and patterns. In his textbook, he offers a full, truly inclusive overview of the subject. Metaphorically speaking, Igor has created a “periodic table of elements” for political space, arranging them by levels and degrees of complexity.

The ambitious idea behind his work and its extensive scope do not take away from the highly thorough and accurate academic research into every aspect of political geography. All the elements of the “periodic table” are very well explained, structured, and supported by evidence and facts.

The main result of his thorough labors is an inclusive and detailed thesaurus serving as a rather promising basis for professional metalanguage in political geography.

Igor Okunev’s textbook is based on his own course taught both in Russian and English in leading Russian universities, as well as on his diverse research projects. Besides, Igor as a true geographer draws inspiration from his sincere passion for adventure and exploration from his youth till maturity making his visit climes and spaces. The author’s love for political geography will hopefully prove to be so contagious for the readers that they will immediately embark on the thrilling journey across the world political map. I would even hope that the readers – just as Igor himself – would explore the broad world around with all the ←17 | 18→extraordinary things both the world and its representation in Igor’s textbook have to offer.

Mikhail ILYIN, PhD

Professor of Higher School of Economics and MGIMO University

Head of the Center for Advanced Methods of Social Sciences and Humanities

in the Russian Academy of Sciences

Introduction to Political Geography

This chapter is introductory and at the same time generalizing for the entire textbook. It defines the subject, methods, and subdisciplines of political geography. It gives the general idea of the principles, levels, and elements of the political and territorial organization of society. If in the next chapters each level and its elements are considered separately, this introduction offers an integrating model of the structure of the world political map.

Political Geography is a discipline concerned with the spatial dimensions of politics.

This course is an introduction to the study of political science, international relations and area studies, providing a systemic approach to the spatial dimension of political processes at all levels. It covers their basic elements, including states, supranational unions, geopolitical systems, regions, borders, capitals, dependent, and internationally administered territories. Political geography develops fundamental theoretical approaches that give insight into the peculiarities of foreign and domestic policies. The ability to use spatial analysis techniques allows determining patterns and regularities of political phenomena both at the global and the regional and local levels.

§ 1. Subject Matter of Political Geography

Political geography draws knowledge from political science and geography. The former studies the political aspects of social activity or, in other words, setting and reaching goals in society, the two processes linked to shaping the institutional structure of the state. The latter focuses on the spatial dimension of both natural (physical geography) and societal (social geography) processes on the Earth’s surface. Thus, ←19 | 20→political geography, a discipline combining two sciences, deals with the spatial dimension of political processes and phenomena.

Try answering the following questions to see if there are some regular patterns of how space impacts on politics. Would:

•the nature of international relations change if every state were located on a separate island?

•the nature of social conflicts change in the absence of state borders and migration restrictions?

•the efficiency of political institutions in the country change if all residents could gather in one room?

•electoral behavior of an individual change if right wingers lived in the east of the state while leftists resided in the west?

The “yes” answer implies that political geography can exist as a separate discipline.

Once, Swiss geographer, Waldo R. Tobler suggested the first law of geography, which runs as “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.” It means that geography studies the attributes of an object that stem from its spatial connections with other objects (horizontal conditionality) rather than its own location and attributes defined by its position (vertical conditionality). It is spatial connections between objects that explain political phenomena in geography. For instance, it would be wrong to say that democracy can arise only in a small-sized state. At the same time, the hypothesis that democracy is more likely to emerge in a state surrounded by democracies looks quite consistent.

The starting point for political geography is the fact that the Earth’s spatial organization preordains the territorial distribution of political power. However, this is not always the case, and there may be exceptions since a range of other factors – apart from the man-made and nature-driven spatial organization of the planet – affect the territorial distribution of political power both internationally and domestically. Research in political geography aims at determining the extent to which the basic hypothesis of political geography is relevant and can explain political processes.

§ 2. Levels of Spatial Organization

Political space resembles a multilayered pie in a way. A political map of the world basically demonstrates only the state level. And even more, ←20 | 21→so it is done with profound distortion. In fact, being physically in one place, we find ourselves at several layers of political space at the same time. Some of them interact while others can exist independently.

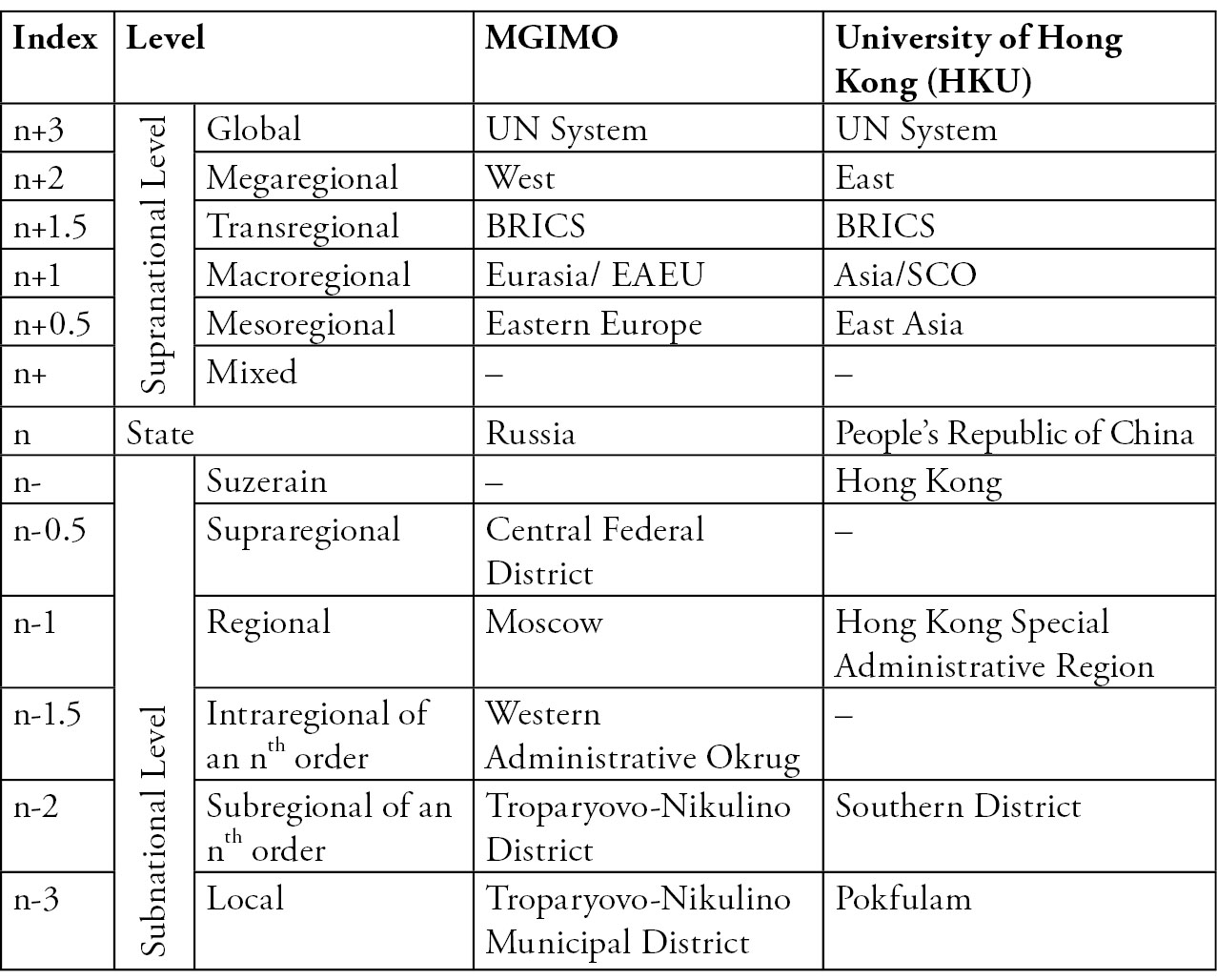

Consider two universities, for example, MGIMO and the University of Hong Kong (HKU) (see Table 1.1).

MGIMO University is situated in the southwest of Moscow. Being integrated in the local community, it is thereby linked to the Troparyovo-Nikulino Municipal District, which implies the local level of political space. Some issues, for example, vital utilities needed for the university to function, are addressed at the intraregional level of the second order (which is the administration of the Western Administrative Okrug) and at the subregional level of the second order (which is the Council of the Troparyovo-Nikulino District, which coincides with the Municipal District). Transportation issues are tackled by the Government of Moscow, at a higher regional level. The government coordinates its policy with the regions of the Central Federal District at the supraregional level. The state constitutes the key political space for the university as the Russian ←21 | 22→higher education policy is developed at the national level. However, it is also shaped in certain aspects by agreements within integration associations to which Russia belongs at the macroregional level (the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and even at the transregional level (BRICS). Finally, there are matters in which the higher education policy is established at the global level, for instance, by the Bologna process or UNESCO. Thus, a MGIMO student’s life is regulated by numerous organizations and bodies simultaneously, with some being hierarchically subordinated to other ones and the others acting independently. These regulation and decision-making institutions are dispersed across different levels of political space, whose cohesion nevertheless remains intact. Study a similar structure of the political space for an HKU student. Some levels will be new while some others will not function at all. Moreover, some levels of political space, like global or transregional, are the same for students of MGIMO and the University of Hong Kong while others are not. In other words, we share the levels of spatial organization with someone all the time, but we are separated from them at the same time.

The state (or national) level is the only basic level. It is the one shown on the political map of the world. The existing system of international relations is the interstate one; that is, it is an interconnected system of relations between states since initially; only the state has the fundamental right to sovereignty or the authority to establish its own rules exercised within a certain territory, with sovereignty regarded as the main political capital. By exploiting it and developing mechanisms to maintain it, states create a pyramid of upper and lower levels of political space, namely the subnational level and the supranational level.

The mixed level, the one between the state level and other supranational levels, and the suzerain level, the one between the state level and subnational levels, constitute the auxiliary levels. They are not fully fledged levels. They create transitional zones in the structure of political space, which are deprived of true state sovereignty. However, these zones are directly bound to a state. International territories, internationalized entities, and territories with the mixed regime belong to the mixed level category, while dependent territories are placed at the suzerain level.

The regular levels of political space (three supranational levels – global, megaregional, and macroregional – as well as three subnational levels, including regional, subregional, and local) cannot establish the ←22 | 23→international system on their own unlike the state level. Nonetheless, they are full-fledged regularly and universally functioning levels. The global level, which embraces international organizations bringing together countries across the globe, as well as other platforms for global dialogue, sees the efforts to work out comprehensive political solutions to some issues, like banning weapons of mass destruction or combating climate change. The megaregional level, comprising large geopolitical dichotomies (the West–the East, the North–the South, the Center–the Periphery, the Sea–the Land, etc.), witnesses the coordinated efforts of large groupings of states that oppose the rest of the world. Regional international organizations and integration associations, which are traditionally continent wide (for instance, the European Union), function at the macroregional level. The regional level is shaped by a system of first-order spatial organization while the subregional level contains a system of second-order spatial organization. There may be more subregional levels, up to five in real life. This will depend on the number of levels of administrative state division. Finally, the local level is represented by municipal self-government bodies. It is not the lowest level of politico-territorial division. Rather, it is an independent level, which is not bound by the state’s executive authorities, the vertical power structure. Local issues are addressed at this particular level.

Optional levels may be omitted if irrelevant. They arise in specific situations and allow building relationships between regular levels. For example, there is a supraregional level, the one between the state level and the regional one, in Russia. It is where the state systemizes its regional policy in federal districts. The same interaction can be established between the regional and supraregional levels of the second order or between subregional levels of lower orders. This level will be referred to as intraregional. Optional levels can be found above the basic state one as well. Sometimes, some countries form separate groups to ensure closer cooperation within the microregion. Take, for example, the Visegrád Group in Europe. This is the mesoregional level of political space. The megaregiona and macroregional levels can generate similar structures (for instance, BRICS). In this case, it will be the transregional level.

The spatial organization is illustrative of the key functions of territory in socio-political processes. On the one hand, it combines different politics layers into a cohesive multilevel process (the integrative function). On the other hand, it splits the mentioned process into levels, which gives rise to development dichotomies (native–alien, internal–external, etc.), which is a fragmenting function.

←23 | 24→§ 3. Principles of Spatial Organization

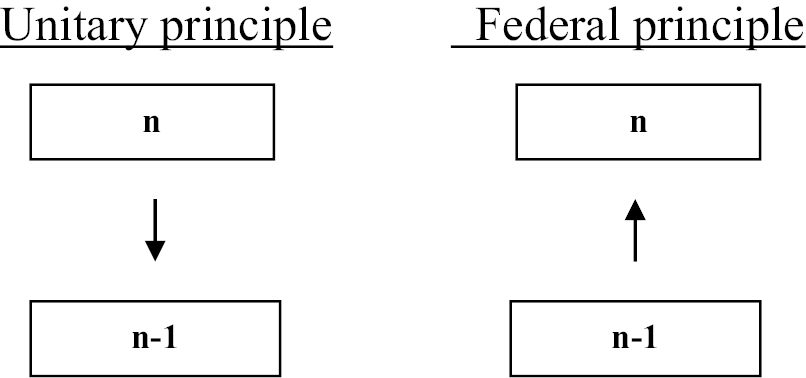

Social interaction occurs both within levels and between them. There exist two basic interaction models between the levels of spatial organization, the unitary one and the federal one. To better grasp their essence, let us go back to the very roots of the theory of federalism.

The conception of state sovereignty proposed by German philosopher Johannes Althusius, the father of federalism, suggests that state formation constitutes the unification process incrementally embracing all levels of social and political organization, from the family, the collegium, the craft guild, the church to the province and the state. Individuals united in families and corporations of their own free will form a consociation (a community); a province unites communities while the union of provinces and cities gives rise to a state. The pyramidal socio-political hierarchy, from the lowest level of self-governing rural and urban communities up to an all-embracing union or state, was perceived by the scholar as a system of federal entities based on the social contract. Thus, Johannes Althusius sees federalism through the prism of the relationship between the political levels, the central one, and the regional one.

The philosopher’s approach to federalism suggests that this principle can be applied to the individual level as well as to the state one. Apart from the levels on the political map of the world, he names social levels. He believes that the federal model can be used to form families, industrial corporations, and other institutions. In other words, federalism can be regarded as a principle of spatial organization as well as a type of state territorial structure. It can be used by various public institutions which may emerge, develop, and function along in accordance with the model. In this case, federalism as a philosophy or theory suggests that the lower levels of the institution (its parts) form the institution by delegating part of the functions to it.

➢The unitary principle of spatial organization implies that authority is vested with a higher-level entity, which is why a higher level of spatial organization institutionalizes a lower one.

The federal principle of spatial organization implies that authority is vested with a lower-level entity, which is why a lower level of spatial organization institutionalizes a higher one.

←24 | 25→The general schemes how the principles of spatial organization are implemented in society will ultimately look like the ones given in Figure 1.1.

Typically, in a unitary state central power determines regional power; that is, it defines the composition and status of the regions. In the meantime, regions can be granted statuses of administrative and territorial units or autonomies. Political rights – the autonomy status – may even be conferred on all the constituent regions. The federal principle is the opposite one. In a federal state, the regions (the regional authorities) form the state (the federal government) by delegating part of their power to it.

We have studied various forms of state territorial division. However, another advantage of the approach based on the political principle of relations is that it can explain and systematize the principles of spatial organization implemented at all political levels. The matter is that the patterns of relationships similar to the given one can be implemented at other political levels as well as at the state one.

The regional levels see the application of the principles found at the state level. Regional unitarism is the type of territorial division, which envisages the division of a region of the first order into regions of the second order, with the rights of the latter defined by the former. Regional federalism is typified by the opposite pattern, with a region of the first order running along the principles set out by the regions of the second order.

These principles are applied at the lower levels of the political map. There exists regional unitarism of the second (third, etc.) order. Theoretically speaking, there may arise regional federalism of the second (third, ←25 | 26→etc.) order. The cases of regional federalism of the second or lower order cannot be found on the modern political map of the world, which implies that nowadays every second-order (or lower) region is a unitary entity.

The same principles – the state one and the federal one – shape supranational entities. Supranational unitarism turns out to be the realization of unitary principle of spatial organization under which a supranational entity determines the composition and status of its constituent states. This form of territorial division was characteristic of numerous empires and unions of the past. Such a formation tends to comprise the central authority (metropolis), which decides on the composition and status of the colonies. In this case, supranational federalism is the realization of the federal principle of spatial organization in accordance with which states form a higher-level entity.

The European Union and some projects of supranational unions, such as the Union State of Russia and Belarus, former pan-Arab projects, and others exemplify supranational territorial entities. A global supranational entity can be formed by sovereign states, which unite and form the supranational governing bodies.

The principle that only higher-level federal institutions can exercise control over lower-level federal ones and only unitary institutions can be subordinate to unitary ones constitutes an important peculiarity of spatial organization. Therefore, a federation cannot be part of a higher-level unitary entity while federal subnational entities cannot be found in unitary entities.

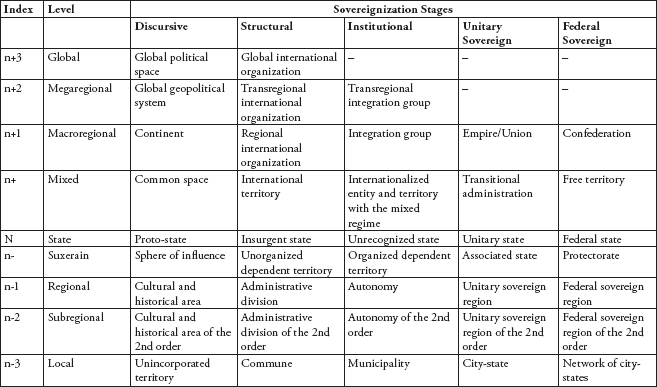

§ 4. Elements of Spatial Organization

Apart from the level where they are created, the constituents of the political space differ depending on the degree of political formalization. To put it differently, at every level constituents seek to become a legal personality, an entity endowed with the right to independently lay down rules on its territory. The stages on the way will be referred to as the levels of sovereignty (see Table 1.2):

■ The discursive level – the entity exists only in people’s imagination, and these ideas are used in the discourse;

■ The structural level – the entity takes the shape of a politically dependent structure, for example a forum for debate or an administrative unit;

←26 | 27→■ The institutional level – the entity functions as a political institution characterized by independent decision-making, but devoid of any traits of sovereignty;

■ The unitary sovereign level – the entity is sovereign and establishes lower-level entities;

■ The federal sovereign level – the entity is sovereign and is established by lower-level entities.

At the global level, there exists a discursive unit, a unified international community, which is often referred to when a universal opinion is meant. Global bodies, such as the UN, which act as permanently functioning platforms for world states to exchange opinions and find consensus, are the building blocks of the global level. Nowadays, there are no global entities of a higher level of sovereignty, and they are unlikely to emerge even in the long run.

At the megaregional level, the parts of global geopolitical systems (the West–the East, the North–the South, the Center–the Periphery, the Sea–the Land, etc.) are discursive entities while transregional bodies (e.g., BRICS) are structural ones. This level witnesses new, better-formalized entities. They are transregional integration groups (for instance, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which are independent players on the world stage, with some of their decisions binding on their member states.

At the macroregional level, discursive (the world’s continents such as Europe), structural (regional international organizations, say, the Council of Europe), and institutional (regional integration blocs, the European Union in particular) elements coexist with fully fledged sovereign entities that rest upon unitarism (in the form of empires or modern unions such as the Commonwealth realms) or federalism (e.g., confederations represented by the Union State).

The basic state level reflects evolutionary changes in the political map on the way to a full-fledged sovereign state. Everything starts only with the notion of statehood, which takes the form of a proto-state (Catalonia). While struggling for independence, such an entity acquires structural features, just as it is the case with Somalia’s insurgent region of Puntland. With the emergence of an unrecognized state, they are complemented by political institutions, just as it happened in Transnistria. After gaining international recognition, the territory transforms into a sovereign unitary or federal state.

←27 | 28→ ←28 | 29→When it comes to the auxiliary levels, they are typified by indirect sovereign units varying in organizational forms. The mixed level, the one between the state level and other supranational levels, includes predominantly discursive zones, which are the common heritage of humankind (outer space and celestial bodies); international territories structured by states and regulated by treaties (the high seas and international airspace); internationalized entities and territories with the mixed regime, which are partly governed by sovereign states (exclusive economic zones); sovereign entities supervised by the international community (for instance, the transitional administration for Brčko District in north-eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina); and, finally, free territories (Svalbard). The suzerain level, the one between the state level and subnational levels, is characterized by loosely structured spheres of influence (particularly, the Warsaw Pact’s Cold War-era members); unincorporated unorganized territories (American Samoa); unincorporated organized territories (Danish Greenland); and those which have reduced their sovereignty in favor of other states, namely associated states (New Zealand’s Niue Island) and protectorates (the Swiss-Liechtenstein protectorate arrangement).

Both regional and subregional levels share the same components, which merely function at the first, second, and lower levels of the administrative division. They involve unstructured cultural-historical areas (Lapland and Friesland); formal administrative units which, however, lack political autonomy (Odessa Oblast and Odintsovsky District); politically autonomous regions (the US State of Texas and the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture); and sovereign regions (a kind of a state within a state) of unitary (South Africa’s former Bantustans, or homelands) or federal (the Muslim-Croatian Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina) character.

Finally, at the local level, there exist unstructured and unincorporated areas (as it was the case with the port of Sabetta on the Yamal Peninsula before it gained its legal status); structured communes without a legal personality (kibbutz communities in Israel); municipalities exercising legislative powers (the Spanish city of Giron); and sovereign city-states (Singapore) and networks of city-states (the former Hanseatic League).

←29 | 30→§ 5. Research Methods in Political Geography

Although contemporary political geography uses traditional qualitative and quantitative research, a number of special tools of analysis are also available:

■ mapping or cartography denotes an operation that associates different political objects and phenomena to geographical locations. It makes it possible to align or distribute objects relative to one another. The next step is searching for the closest entities to the designated object and analyzing the relevant location patterns. Finally, the overlay of cartographic information, which implies taking different thematic maps of the same area and placing them on top of one another to form a new map, and map scale changes can help to gain new information about spatial distribution patterns;

■ clustering refers to grouping data items into regions (spatially contiguous clusters) or chorions (space-time clusters), which allows arriving at a conclusion about social structures and political processes. The process involves distinguishing territories on the basis of some feature or condition and its relationship and compatability with other spatial elements;

■ spatial analysis defines the search for those location patterns that explain the nature of political objects and processes. The method helps to identify key and secondary features of the space, spatial dependence vectors, and spatial barriers to dependence, and draws the hierarchical structure showing the interdependence of elements and levels of spatial organization.

❖ Let us look closely, say, at the Arab-Israeli conflict. While doing the mapping, we can associate the modern boundaries of Palestinian political entities with natural regions, former administrative borders, ethnic enclaves, and economic zones, thus specifying the nature of the Arab-Israeli dispute. Geographic clustering enables one to establish stability and tension zones, link them with the features of the territories, their socio-economic portrait, and their dependence on external forces, and make suggestions about pressure points and their defining factors. In turn, spatial analysis makes it possible to establish the correlation between political instability and the territorial ←30 | 31→organization of the Palestinian National Authority. It also allows determining the key dependence vectors of a future Palestinian state upon its Israeli neighbor and the barriers that will lay the basis for a more detailed model of peaceful cleavage.

Details

- Pages

- 474

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782807616219

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782807616226

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782807616233

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9782807616240

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17747

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (January)

- Keywords

- borders capitals spatial analysis techniques geopolitical systems political geography spatial dimensions of politics supranational unions

- Published

- Bruxelles, Berlin, Bern, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 474 pp., 33 fig. b/w, 54 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG