Reading Monuments

A Comparative Study of Monuments in Poznań and Strasbourg from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction

- The Shape of Monuments

- Space and Place

- Monument as a Thing

- Monuments from a Gender Perspective

- A Bio-graphical Attempt

- Monuments and Politics

- Politics of Memory

- Identity: From Regional Politics to National Politics

- Monuments and Affect

- Veneration

- Demolition

- Supplements

- Conclusion

- List of Figures

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Małgorzata Praczyk

Reading Monuments

A Comparative Study of Monuments in Poznań and

Strasbourg from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Translated by Marcin Tereszewski

Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche

Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at

http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the

Library of Congress.

The Publication is funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the

Republic of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the

Humanities (Universalia 21. No: 0038/NPRH/H12/84/2017, 2017-2020). This

publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Ministry cannot be held

responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

This publication was financially supported by the Adam Mickiewicz University in

Poznań.

Translated by Marcin Tereszewski

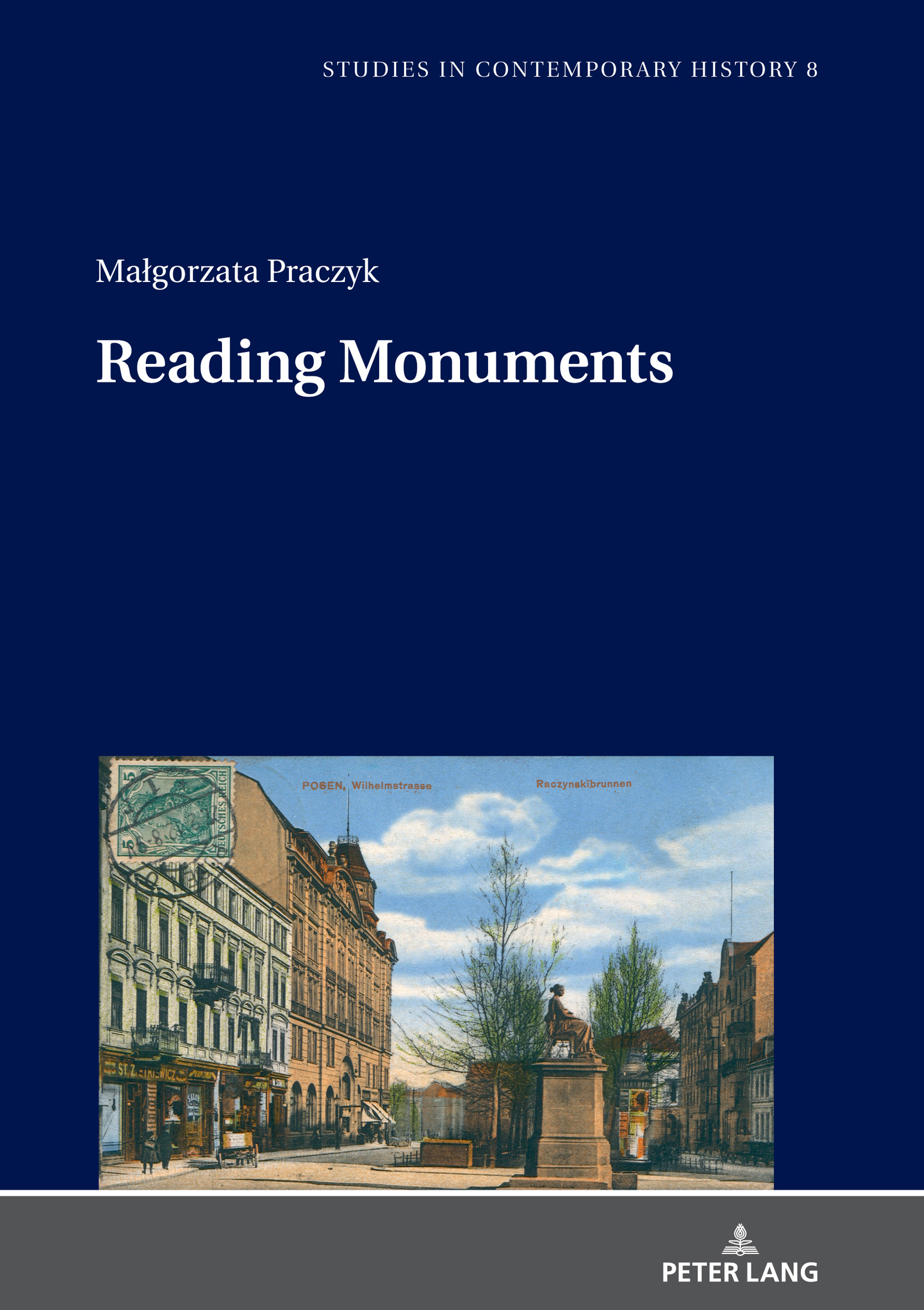

Cover Illustration: Wilhelmian Alley and the statue of Hygieia. Poznań. From the

collections of University Library in Poznań. Courtesy of the University Library in

Poznań.

ISSN 2364-2874 · ISBN 978-3-631-67675-2 (Print)

E-ISBN 978-3-653-07148-1 (E-PDF) · E-ISBN 978-3-631-71106-4 (EPUB)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-71107-1 (MOBI) · DOI 10.3726/b16685

Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this

license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

© Małgorzata Praczyk, 2020

Peter Lang – Berlin · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien

This publication has been peer reviewed.

About the book

Małgorzata Praczyk

Reading Monuments

This book tells the story of monuments in two cities that share a parallel and turbulent history: Strasbourg and Poznan. With the Franco-Prussian War begins the well-known story of the destruction and erection of memorials. This book not only explains the mechanisms related to how memorials have functioned in the past, but also contributes to our understanding of current modes of their perception. It analyzes their material shape, the problem of affect, and their meaning, not only in relation to the political context and the work of memory. This book shows how the form of monuments reflects the social understanding of such basic questions as the perception of nature, gender issues and the image of those who are in power, and how, and in which aspects, those kind of objects actually change the city space we live in.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Introduction

Among the cities located on the opposite ends of the Hohenzollern Empire, there are two whose parallel histories had a particularly strong influence on their urban space: Strasbourg, located in the Alsace region and Poznań in Greater Poland. The last quarter of the nineteenth century saw the expansion of the Prussian Hohenzollern Empire, whose western border reached the Rhine. As a result, after the Franco-Prussian war, the borders of the empire were absorbed by Alsatian Strasbourg. Already at the end of the eighteenth century, Poznań was located on the opposite end of this huge state. Near the end of the nineteenth century, both borderland centers were connected by a common history, one that is reflected by the history of erected and destroyed monuments. The history of monuments envelops changes in the political, social and cultural situation of these two, seemingly different and distant cities, and especially the communities that inhabit them. The history of Strasbourg’s and Poznań’s monuments is not only an extremely sensitive indicator of what has happened in cities and with cities, but above all, is an interesting example of how such objects function in public space, their role and the extent of their social impact.

Monuments are not, contrary to what Robert Musil claimed, neutral or passive actors in public space1. In exceptional, liminal moments of history, they evoke and channel powerful human emotions, whilst entering mainstream political events. This is what happened on the night of November 20–21, 1918, when Prussian monuments disappeared from Strasbourg, and when, on the night of April 3–4, 1919, the residents of Poznań dragged the plinths of German monuments onto Wilhelm Square. Anger and outrage mixed with joy and satisfaction were channeled in the act of destruction, undoubtedly serving as an emotional safety valve.

However, it is not only in liminal moments that monuments actively participate in the life of cities and their inhabitants. They also play important roles on a daily basis when, seemingly unnoticed, they complement the surrounding space. They serve as meeting places, appear in photographs, you can climb them or wear them on the shirts of your favorite sports teams. They are, in effect, the companions of city dwellers, passers-by, tourists in everyday life, not only during celebrations dedicated to events or people who they commemorate.

←11 | 12→In this book, I attempt to approach monuments from the perspective of the relationships that take place between them, the people and the space in which they are located. These considerations will center around three main levels of interpreting monuments: firstly, their shape, secondly, the politics of commemoration, and, finally, the problem of affect. I consider these levels crucial if one is to understand the complexity of monuments. Examples of monuments analyzed here are located in two cities: Poznań and Strasbourg in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For the purposes of these considerations, a monument is defined as an object that functions actively in public space and which communicates meanings both on the level of its materiality and on the level of the commemorated content that immerses it in history2. I intend to show that monuments are a kind of performative objects, whose agency is manifested in their material shape and when they constitute a catalyst for social and political change.

I find the comparison of Poznań and Strasbourg interesting for several reasons. The first has to do with their history3. Poznań was annexed into the Kingdom of Prussia as a result of the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, whereas Strasbourg was annexed after Prussia’s victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). The same conflict gave rise to the German Empire, on whose western border the capital of Alsace was located, and on the east – the capital of Greater Poland. Both cities shared a common nationality for over forty years. Both of them gained the rare status of imperial residences (kaiserliche Rezidenzstadt). It was during this period that representative German districts were built around carefully designed squares, where monuments manifesting the Germanic spirit were erected. These monuments were meant to demonstrate that these cities belong to one national ←12 | 13→organism. Then, after 1918–1919, both cities became part of separate states, France and Poland; however, already during World War II, they found themselves again within German borders as part of the Third Reich. After 1945, they once again were returned to France and Poland, but this time their histories were divided for a longer time, as for over forty years these cities found themselves on the opposite sides of the Cold War Iron Curtain. This situation changed after 1989, when Poznań, together with all of Poland, entered the European democratic realm. The next event that brought these cities together as part of a larger political body was Poland’s accession to the European Union.

Poznań and Strasbourg also have similar characteristics. Both are provincial cities, each of which is its own way also a borderland city, which meant that, in their turbulent histories, they had to struggle with multiculturalism, the changing nationalities and national identities of the people inhabiting them. However, this does not mean, of course, that both cities share the same problems regarding nationality and identity issues. Undoubtedly, a strong sense of Alsatian identity is clearly felt in Strasbourg. In the case of Poznań, it is difficult to talk about the Greater Poland identity of Poznań’s inhabitants, although there persists a sense of separateness, rooted in the region and its history, in particular in relation to nineteenth century history. In Poznań, identification with Polishness is certainly more pronounced than Strasbourg’s identification with France.

Details

- Pages

- 216

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631676752

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631711064

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631711071

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653071481

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16685

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (May)

- Keywords

- Memory studies Anthropology of space Theory of history Comparative history European history Cultural studies

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 216 pp., 27 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG