A Very Special Life: The Bernice Chronicles

One Woman’s Odyssey Through Twentieth Century Jewish America

Summary

Her life story reflects much of the development of American Jewry during the middle of the 20th century: the Great Depression, the Second World War, the development of Zionism, the response to the new State of Israel, and the development of Jewish suburbia. We follow Bernice's school years during the Depression, her connection with the Bronx Y, her college studies, her stint in the Women's Land Army, study trip to Israel in 1949, and marriage to Arthur Schwartz, a young army veteran and social work student from Nyack, NY.

After the couple's odyssey through several East Coast Jewish communities, they and their sons settled in Teaneck, New Jersey. We follow Bernice's response to her oldest son immigrating to Israel, and the couple's move to Riverdale, NY and life there during their "Golden Years" in the 21st century.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

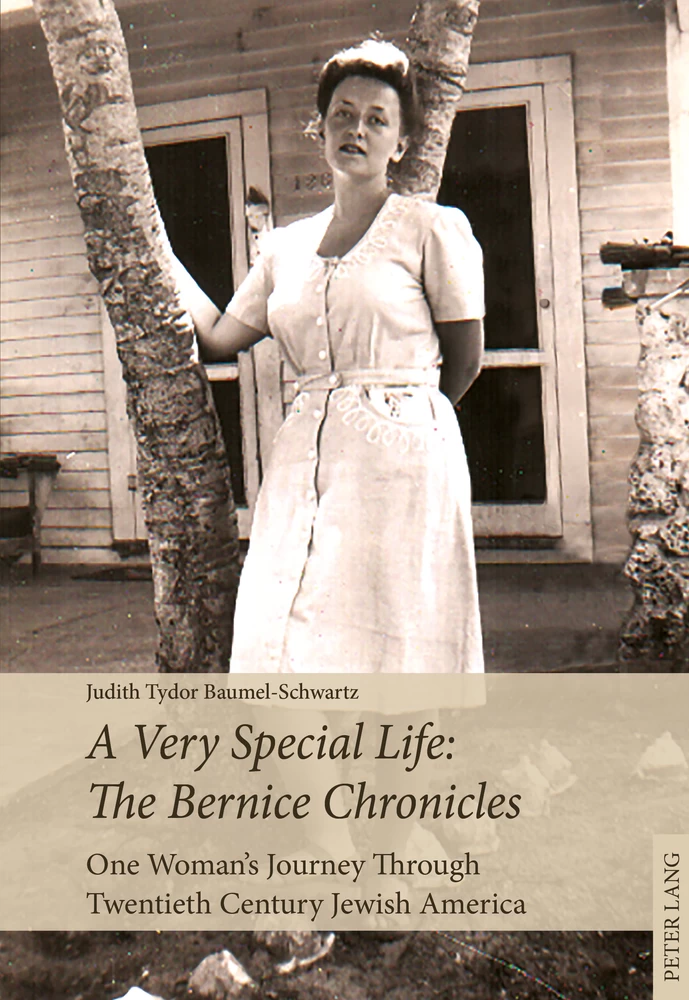

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Introduction to Part I: The Genesis of a Book

- Chapter 1 How it all Began

- Chapter 2 The Education of Bernice Cohen (1923–1939)

- Chapter 3 The War Years and the Women’s Land Army (1939–1945)

- Chapter 4 The Bronx Y: Bernice’s Home Away From Home (1930–1951)

- Chapter 5 Israel 1949: “A Wilderness of Magnificent Beauty”

- Introduction to Part II: The Courtship of Bernice Cohen

- Chapter 6 Arthur Schwartz: A Boy From Nyack

- Chapter 7 East Coast Adventures (1950–1960)

- Chapter 8 The Schwartzes of Teaneck (1960–1999)

- Chapter 9 Closing the Circle: A Son Makes Aliyah (1967–1974)

- Chapter 10 The Schwartzes of Riverdale (1999–)

- Epilogue: Reconstructing a Family

- Family Tree

- Glossary of Foreign Terms

- Bibliography

- Photographs

- Index names

- Index places

- Index organizations, institutions

Introduction to Part I: The Genesis of a Book

Sunday February 17, 2013 was a cold day in New York City. After a pleasant week of moderate weather, a snap of winter reality returned with howling winds and frigid temperatures. The one consolation was the clear skies, affording New Yorkers an unimpeded view of their city. Many chose to spend the day indoors, but others braved the sub-zero wind chill factor to appreciate the almost smog-free atmosphere. On Manhattan’s upper West Side the usual groups could be seen at midday: pet owners walking their dogs, joggers in Riverside park, parents out with children, all breathing the almost-frozen air that cut through your lungs like a knife.

Among those then outdoors on the upper West Side were some 50 people of diverse ages, making their way from various directions to the social hall of a synagogue on the corner of West End Avenue and 100th street. All were friends and relatives of my in-laws, Bernice and Arthur Schwartz, whose children had invited them to the couple’s “90th year celebration” being held there. Bernice’s 90th birthday had indeed taken place a few days earlier. Arthur’s would only be 90 in a few months, and the title of the party was chosen so as not to tempt fate.

As people entered the hall and began filling their plates with bagels, lox, and quiches from the buffet, Bernice looked around the room at those who had been closest to her during much of her life. Her husband, dressed in a red turtleneck and warm corduroy jacket against the cold, basking in the love of friends and family. Her three sons, the oldest of whom had flown in from Israel for the occasion. Two of her daughters-in-law, and her American grandchildren. Her Israeli granddaughter with her husband, doing a year of his surgical residency in New York City. Their two little boys, her great-grandsons. Her sister, brother-in-law, and their family. She and her sister had either lived together, or around the corner from one another, for over sixty years. Friends that she and Arthur had made throughout their lifetime, including her oldest girlfriend from Hunter College who she had met over seventy years ago. In-laws, cousins and relatives who had come to New York especially for the occasion. A room filled with her past, present, and future. ← 9 | 10 →

Soon it was time for speeches. One of the speakers for the family, her oldest son, my husband Joshua, quoted a Talmudic story about a father planting a fig tree that takes years to bear fruit, so that his children could eventually enjoy its fruit. “This is how my grandparents acted”, he continued, “caring, planning for, and helping my parents just as my parents later did for me, my brothers, and ultimately, our extended family.” Describing his parents as the perfect couple, he pointed out that they indeed prepared their children for life, but not at the expense of their own lives which they had lived and were still living to the fullest. That is the lesson that we can learn from them, he concluded: to know how to reach that equilibrium.

After all the speakers it was Bernice’s turn to respond, which she did by thanking everyone for coming and addressing the party’s purpose.

“What is this getting older? Who are you and what becomes of you?” she said to all the assembled. “You are getting on, you are a ‘Golden Ager’, you are a statistic, you are a study. You get up in the morning, put your feet on the ground and say ‘Thank G-d, another day’. You also think, ‘Maybe I shouldn’t have quit my job, maybe I shouldn’t have retired.’ But there is a great plus to it. If the weather is bad and you don’t feel so great, you turn around and go back to sleep.”

“There were three things that made me determine that I was getting older.” She continued. “One was that I looked in the mirror. The second one was that you walk into the subway or a bus and someone will get up, even though you may be stronger than that person giving you the seat. The third is the awareness that your children are as eligible as you for AARP (American Association of Retired Persons). And that is the clincher that all of a sudden you are not the same.”

“My brother-in-law Morris’s father used to say ‘we aren’t golden age, we are brass’. But as I was polishing my brass Shabbos candles, I realized that brass isn’t bad. You polish it and back it comes to its full warmth and glow, just like it did when it was new. And that’s true for us as well.”

Ending her response with the Yehi Ratzon (“May it be Thy will”) said on Shabbat after candle lighting, she asked the Lord “‘to show favor to my dear husband, our beloved children, their children, and their children, all our relatives, friends and their dear ones, and me, that you grant us all a long life, that you remember us with compassion, that you bless us all with great blessings’.…and now, in the spirit of ‘Fiddler on the Roof’, to all a ‘lechayim! (to life!)’”.

It was a party to remember, so said everyone who was there. I, however, could not be there with my in-laws, as I was in Israel, caring for my own invalided mother. My husband had included me in his opening greetings, I was sent dozens of pictures and a video of the speeches and participants, but it wasn’t the same. All day long I had thought about the party and how much I missed everyone there. Late that night, when my mother-in-law returned from the gathering, I received the email I was waiting for, in which she described the events of the day.

“It was a wonderful party and you were greatly missed”, she wrote me, listing who had been there, and what had been done and said. Summarizing her talk, she ended her message with the words “I have been blessed with a very special life, and I am grateful for all that I have been able to experience and to do, both for myself and for others, throughout the years.”

Bernice Cohen Schwartz and Her Generation

This book tells the story of that very special life which my mother-in-law described in her message to me, and through it, the story of an entire generation of Jewish women who came of age in America during and right after the Second World War. They were the daughters, and in some cases, like my mother-in-law, also the granddaughters of 2.2 million Jewish immigrants who had come to America during the Great Wave of Immigration (1881–1914), mostly from Russia, Rumania, and Austro-Hungary.1 For those Jewish immigrants, America was the Goldene Medine (the golden country) which had given them a new home. Their loyalty to America was absolute, but unless they had come at a young age, American society often remained somewhat foreign to them and sometimes even threatening, often causing them to retain a certain degree of disconnect throughout their lives.

In comparison, this generation of young women, children and in some cases, also grandchildren of those immigrants, could be described as being “at home in America” to use the term coined by Deborah Dash Moore ← 11 | 12 → in her study of second generation New York Jews.2 Most created a life for themselves that was fully compatible with American values, but at the same time, solidly Jewish. Leaving their parents’ working-class communities, the majority ultimately joined the middle class mainstream, confident in their ethnicity and unafraid to show their Jewishness. Looking for an institutional expression of their faith and acculturation, they developed the synagogue-center, a hybrid establishment serving both their religious beliefs and cultural needs. Attempting to reconcile the values of their parents’ generation with their American pluralistic character, they turned to the liberalism of the time and communal Jewish philanthropy as a means of expressing their ethnicity.

The “first” and “second” generations were similar in many respects, but differed in others. One was geographic. Similar to the immigrant generation, much of this new generation centered around the greater New York Metropolitan area where almost half of America’s Jews lived during the decade after the First World War. But unlike the immigrant generation in New York City, which had been concentrated primarily in Lower Manhattan and later in Harlem, by the end of the 1920s the majority of this new generation was living in the emerging neighborhoods of the Bronx or Brooklyn, the fastest growing Jewish areas in the city. In 1923, the year that Bernice was born, over 20% of New York’s Jews lived in the Bronx, her birth borough, and by 1930 that number had risen to 32%.3 The “second generation” was also a rapidly growing generation. By 1940, the under 20s – the group to which Bernice and this new generation belonged at that time – made up a third of the Jewish population of New York City.4

Another difference was language. While the “first generation” of immigrant Jews often expressed the time-honored and normal pattern of immigrant loyalty to their “home language”, the key linguistic shift took place ← 12 | 13 → among the “second generation” – their children – who were completely at home in English, with little nostalgia for the language of their parents.5 But the dichotomy was not absolute. Although few members of the “second generation” would buy a Yiddish newspaper, most, nevertheless, had a working knowledge of the language. Even those children who could not read or write Yiddish often retained a passive knowledge which made them into what is lexically known as “fluent comprehenders”.

If the “first generation”, the “immigrant generation”, had been defined by their immigration, the next generation did not begin with a pivotal definitive event that gave it definition. One might say that its definitive event, the one that changed its character and later, its future, was the Second World War, which only began as its members entered adulthood. Taking large numbers of them away from home for the first time, it laid the groundwork for a post-war demographic shift of New York City’s Jews. While in most cases, the immigrant generation spent their entire life in an urban environment, even if they had come from a rural one in Europe, the same could not always be said for their children. Large numbers of this new generation had been raised in a culturally distinct urban enclave, but did not remain in one after reaching adulthood. Life in suburbia, to the extent that there was one, was an alien concept to most of the immigrant generation, but not for their American-born children, a great number of whom spent their middle years in bedroom communities and more outlying areas, many of which were created or developed only after the war.

Going off to war also caused communication difficulties between the generations. As we saw earlier, much of the immigrant generation was still more comfortable in Yiddish than in English, while their American-born children, usually able to understand some Yiddish, rarely knew how to write in any language other than English.6 The result was a gap, sometimes of several years, when communication between certain immigrant parents and their American-born children, who either served overseas or were stationed in a distant part of the United States, was minimal.

Another result of the war among some of the “second generation” was a trend towards secularization or at least relinquishing Jewish tradition ← 13 | 14 → in order to fit into the American panorama. Army service exposed many of them to unfamiliar, non-kosher food for the first time, and even some formerly traditional Jewish young men of that generation found themselves “eating ham for Uncle Sam” in order to prove themselves equal soldiers.7 There were those who returned to a more traditional life after the army, but for others, the experience conditioned them to adopt a more “American” lifestyle in matters of Jewish tradition. In general, the military afforded some of this generation their first close contact with Gentiles, accelerating their later structural assimilation into the America mainstream.8

Despite the impact of the Second World War, and particularly military service, on the “second generation”, the war was an event that affected not only them, but the country’s entire population. Thus, it may have been definitive for their generation, but it was not unique to them.9 This “second generation” was therefore defined, first and foremost, by its relationship to the “first generation”, which is how it became the “second”. And as such, it functioned as a somewhat transitional group, blending immigrant communities and assimilating them into a new society.

Yet the immigrant-second generation split, at least among American Jews, was not necessarily a great divide, and the two groups retained much in common. A great number of social and cultural values were mutual to both generations, such as a respect for parents, drive for education, and ethnic solidarity. And while three generations usually no longer lived under one roof, as had at times been the case earlier in the century, the children and grandchildren of immigrants often continued to feel a sense of responsibility towards the previous generation, particularly as the members of that generation grew older.

In many ways, the story of Bernice Cohen Schwartz’s very special life is the story of this generation of young women who were “at home in America”. Born in 1923 to American-Jewish parents of Eastern European extraction, she was raised in a traditional Jewish home in the Bronx but received a modern American education. Throughout her elementary, high school and college years, her home-away-from-home was the nearby Bronx Y, a prototype of a synagogue-center, where she eventually directed the Teenage Division. Bernice supervised graduate students in social work ← 14 | 15 → doing their required service hours at the Y, and eventually married one of them, Arthur Schwartz.

Like much of her generation who believed that a married woman should stay home and raise her children, she spent the first decade-and-a-half of married life at home raising three sons, and only returned to work when her youngest entered school. Like many of them, she chose to live in a suburban (Jewish) community to give her children a yard and open spaces for play. But she and Arthur also made sure to be close enough to their aging parents in order to keep an eye on them and offer assistance if necessary. Active in their shul (synagogue) and her sons’ Jewish Day schools, Bernice continued her volunteering after retiring. But aware of the difficulties of living in suburbia as one aged, after she and Arthur retired, she eventually found them an apartment in Riverdale, a Bronx neighborhood populated partly by older Jewish retirees. Thus they joined that generation’s “exodus from suburbia”.

In other ways, however, her story differs somewhat from that of most young Jewish women of her generation. Raised in a traditional Jewish home in the Bronx, she experienced life in a four-generational household surrounded by extended family. The grandparents and great-grandfather who were part of that household had all been immigrants, but unlike most Jewish girls of her age, on her mother’s side she was already a second-generation New Yorker, while her father had arrived at the turn of the century as a toddler and remembered nothing from Europe. Although in many ways she was typical of the “second generation”, by virtue of her mother’s American birth she was, in fact, part of the lesser explored “2.5 generation” of that time.10

At a time when many Jewish immigrants were Yiddish speaking, and their children had a somewhat passive fluent understanding of the language, Bernice only learned Yiddish – her grandparents “secret language” – in Hebrew school classes which she later polished at university; her Yiddish was classroom Yiddish with grammatical rules. During the 1930s when few Jewish educational opportunities were open to girls and young women, in additional to her general studies, she graduated from an afternoon Hebrew High School which taught not only Hebrew but Bible, Jewish Literature, Jewish Philosophy and Jewish Dance. ← 15 | 16 →

Bernice was always an adventurer. When her family refused to let her join the army during the Second World War, during her summer break from Hunter College she volunteered as an agricultural worker in the Hudson River Valley through what was later called the “Women’s Land Army”. In 1949, while studying for a Master’s Degree in Public Administration at NYU, she participated in the first American graduate study trip to the newly born State of Israel, spending six weeks touring the country and wondering whether it would be her future, a dream she only relinquished finally when she married Arthur Schwartz.

Bernice indeed stayed home to raise her children, and ended up in suburbia, in her case, Teaneck, New Jersey, but for the first decade of her married life, “home” was a geographically changing location. During their early years as a family, the Schwartzes temporary “home” moved up and down the East Coast following Arthur’s professional development, where she had to adapt to life in a number of very different Jewish environments.

Not having planned to rejoin the workforce full time until her children were older, she found herself returning to work to support the family when Arthur was unexpectedly offered a graduate fellowship in gerontology at Teachers College, Columbia University. Ultimately directing a therapeutic nursery at Bronx Hospital, she ended up working in the same hospital as Arthur did after he completed his degree – Albert Einstein Hospital. There she once again directed their therapeutic nursery while Arthur became the Director of Community and Education, administering community services through various educational outlets. Only after retiring and moving back to New York City did her life, once again, enter the more standard generational pattern.

The Genesis of a Book

“Every person’s life is worth a novel”, writes Gestalt psychotherapist Erving Polster.11 People often marvel at the events of others and do not notice that their own lives are filled with action, drama and adventure. This was indeed ← 16 | 17 → the case with regard to my mother-in-law, Bernice Cohen Schwartz, when I first broached the idea of writing about her life. But to understand how the idea first came about, we must begin with another person, and a different story, which ultimately also became a book.

Throughout my very traditional Jewish upbringing I often heard the saying mitzvah goreret mitzvah – one good deed leads to another. Until recently, however, I did not realize that the same holds true with books. During much of the year before beginning work on this book, I had explored the history of my mother’s family, and particularly that of my grandmother, Freida Sima (Bertha) Eisenberg Kraus, as the basis for understanding the history of a generation of young Jewish immigrant women who had come to America during the late 19th and early 20th century. The result of that exploration was initially a series of front-page essays published throughout that year in The Jewish Press. With the unending encouragement of both my husband Joshua Schwartz and the indefatigable editor of The Jewish Press, Jason Maoz, I decided to expand the articles and turn them into a book which was published by Peter Lang Publishers in early 2017, entitled “My Name is Freida Sima”.

While writing the articles and later the book, I underwent a personal and family metamorphosis, discovering both new layers of my family’s history and an entire branch of my family of whom I had never known. Most of all, in writing the book I not only rediscovered my own family’s history, but I connected various family members who had not known of each other or of their common heritage, and reconnected others who had not been in contact for years. All in all, it was an exhilarating, redeeming, and positive experience on all levels.

At some point as the series was being published, my mother-in-law, impressed by one of the episodes, wrote my husband a short note in which she asked “and what about me? Aren’t any of my adventures worth an article?!” Although the statement had been made in jest, I asked her whether she would be interested in my writing a short article about her student study trip to Israel in 1949, based on the group’s diary she had kept at the time, and which she had given me to transcribe several years earlier. She reacted positively to the idea and so I went to work, using the journal as a basis for the article and fleshing out the story by asking her dozens of questions about the trip. There was also a pictorial record of the journey – a collection of over 80 photographs she had taken on the trip, including at the half a dozen stops they made during the flight to Lydda airport. ← 17 | 18 →

Originally I had thought of this as a single effort to show her that “her adventures were worth an article”. But when I sent it to the editor of The Jewish Press, his response “so is this going to be a new series?” planted a seed for the future. That future came several months later, when out of the blue, my then 93-year-old newly widowed mother-in-law, informed us that she would be returning to Israel with my husband after his trip to the United States, and would be staying with us for two months, until after her latest great-grandchild would be born in Jerusalem.

Initially we reacted with some surprise. There had been a thought that she might want to come for the birth and stay for the bris (circumcision), as we knew the baby would be a boy. But for two months? I truly love my mother-in-law, but how many daughters-in-law would react to such an announcement, coming from 6,000 miles away, with equanimity? How would we keep her occupied for all that time, especially as my teaching term had already begun? True, we had stayed with her in New York for a week here or there, but what would it be like living together in close quarters, often in rainy winter weather, for weeks on end?

Within days of her arrival the last episode of my grandmother’s series appeared in The Jewish Press. Now I knew that if I was thinking of turning what had begun as a single article about a student trip into a short series of four or five articles, it was time to act. With my mother-in-law in the house I finally had the opportunity to sit with her face-to-face and interview her about her family background, experiences, and opinions. There were family documents that she had already given us in the past to add to this background, and others which could corroborate certain facts were readily available on the internet. Initially hesitant about the project, she ultimately agreed to a short series that would focus on her immediate family and personal experiences.

Details

- Pages

- 434

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034327589

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034329866

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034329873

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034329880

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11245

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (July)

- Keywords

- Gender American Jewish History American Jewish Education American Jewish Institutional Development Immigration Family Studies Genealogy

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2017. 433 pp., 12 b/w ill., 42 coloured ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG