The Anatomy of National Revolution

Bolivia in the 20th Century

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction

- Index of maps

- Chapter 1: Bolivia First!

- Chapter 2: The Devil Incarnate: la Rosca

- Chapter 3: To take a rightful place among the nations of the world

- Chapter 4: All Power to the Labour Unions?

- Chapter 5: The New (Old) Nation

- Chapter 6: Let us Bring Bolivia into the 20th Century!

- Epilogue

- List of abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Resumen

- Index of names

← 6 | 7 → Introduction

I have been interested in Bolivia for the past 30 years. This interest began at the Warsaw University and Main School of Planning and Statistics Inter-University Center of Research on Underdeveloped Economies where I began my research career. Professor Michał Kalecki, the head of the centre’s Board, developed a concept of intermediate political regimes that seemed to fit a number of Third World countries1. He assumed that the Latin American country which might exemplify it could be Bolivia. After 1968, when the centre ceased to exist in its original form, I used to visit the professor who – unwilling to affirm the hysterical campaign against an alleged “Jewish fifth column” – had chosen to retire. It was for my conversations with him that I developed my first text on Bolivia. It later served as the basis for our joint study on that country and my own more descriptive article2.

I later became interested in Bolivia as part of my wider interest in Latin America and other regions. I became interested in the problem of revolution – and after all, the Bolivian revolution of 1952 was one of the most important events of its type in the history of Latin America. I became interested in revolutionary movements that combined elements of social liberation with demands for national independence – of which the Bolivian revolution could serve as a textbook example. I became interested in the problem of modernisation and the road of certain countries “towards Europe” – an issue of key importance to Bolivia in the 20th century, even though of course it was not moving towards Europe in the literal sense.

I was thus interested in Bolivia more or less from the time of the leftist and Marxist Cuban Revolution until the Solidarity strikes in Poland – anticommunist and national. And even though this might sound surprising, I see certain similarities between those two events. Both were marked by elements of a radical struggle to do away with all evil and build an ideal world – which can probably ← 7 | 8 → be said of all revolutionary movements. Another shared element that I see is the struggle for national independence, throwing off foreign economic dominance, and economic development and modernisation. Finally, I see both events as marked by the mutually-reinforcing phenomena of social revolt and a revolt in the name of achieving national ambitions.

All these elements were present in the thinking of many third-world, including subversive thinking in Bolivia. For this reason the title I chose for the present book is a modification of the titles of Huberman and Sweeze’s book about the Cuban Revolution and the classical book on revolutionary phenomena by Brinton, a modification created by the addition of the word “national”3.

I have been interested in Bolivia for so long, in fact, that in the meantime most elites of the world and of Bolivia have changed their minds on the correct road to modernisation. While initially it was generally believed that the instrument it required was the curtailing of the power of the upper classes, state intervention, state control over the means and factors of production and economic planning the current thinking points in the opposite direction. This change is interesting in and of itself and the answer that time will bring to the question of whether the new approach is more effective will be important not just to Bolivia but to the world at large.

While I constantly remained interested in Bolivia, I never had the opportunity to work on the subject of Bolivia as such – there always seemed to be something more urgent to do. Today, I can hardly believe that I have finally written this book. It is based on archival materials produced by US, British, French and Polish diplomatic services, kept at the National Archives in Washington, the Public Record Office in Kew near London, the Archives Diplomatiques in Paris and the Central Archives of Modern Records in Warsaw. The inclusion of archival materials produced by Polish diplomatic services is, by the way, more than just an ornament – in spite of the distance separating the two countries. Poland before World War Two was genuinely interested in Bolivia as a potential destination of émigrés and due to its participation in the League of Nations. The documents used are referenced in the footnotes with their titles, if available, the name of the author, the date and location of their production and location in the archives. In cases where it was impossible to determine the author’s name or it was illegible, it is replaced by the name of the diplomatic post where the document was created. ← 8 | 9 → The file card numbers after the file names are obviously given only in those cases when the files have been paginated.

The archival materials have been supplemented with printed texts, obtained mainly from the British Library and the library of the London School of Economics, as well as research papers, first and foremost the works of Robert J. Alexander, Herbert S. Klein, James M. Malloy, Hans C. Buechler, Charles J. Erasmus and Dwight B. Heath4.

Neither the source materials nor scientific descriptions exhaust the materials which should in fact be studied in the libraries and archives of different countries. And even though in the case of contemporary and modern history this situation is the norm, the inability to use the original Bolivian archives is still unfortunate. Even though those materials are far from ideal, there is no doubt that they contain many valuable items.

In spite of these flaws, I believe that the sources I was able to access present an acceptable picture of the modern Bolivian issues of interest to me. And quite honestly, it is an examination of these issues that interests me more than a monographic study of the very interesting country of Bolivia.

M. K.

22 Feb. 1998 ← 9 | 10 →

1M. Kalecki: Uwagi o społeczno-gospodarczych aspektach >>ustrojów pośrednich<<”, “Observations on Social and Economic Aspects of ‘Intermediate Regimes’” in: ibid, Dzieła, Vol. 5, Warszawa 1985, pgs. 22–29.

2M. Kalecki, M. Kula, Boliwia: przykład „ustroju pośredniego” w Ameryce Łacińskiej, “Bolivia: An Example of an Intermediate Regime In Latin America” in: ibid., pgs. 207–211; M. Kula, Boliwia: latynoamerykańska wersja ustroju pośredniego, Boliwia: A Latin American Version o fan Intermediate Regime „Ruch Ekonomiczny, Prawniczy i Socjologiczny” 1971, nr 1, pgs. 263–278.

3L. Huberman, P. M. Sweezy, Cuba: Anatomy of a Revolution, 1960 (Anatomia Rewolucji Kubańskiej, Warszawa 1961) C. Brinton, The Anatomy of Revolution (1938), New York 1965.

4R. J. Alexander, The Bolivian National Revolution, New Brunswick, N.J. 1958; H. S. Klein, Parties and Political Change in Bolivia 1880–1952, Cambridge 1969; J. M. Malloy, Bolivia: the Uncompleted Revolution, Pittsburgh 1970; D. B. Heath, Ch. J. Erasmus, H. C. Buechler, Land Reform and Social Revolution in Bolivia, New York–Washington–London 1969.

← 10 | 11 → Index of maps

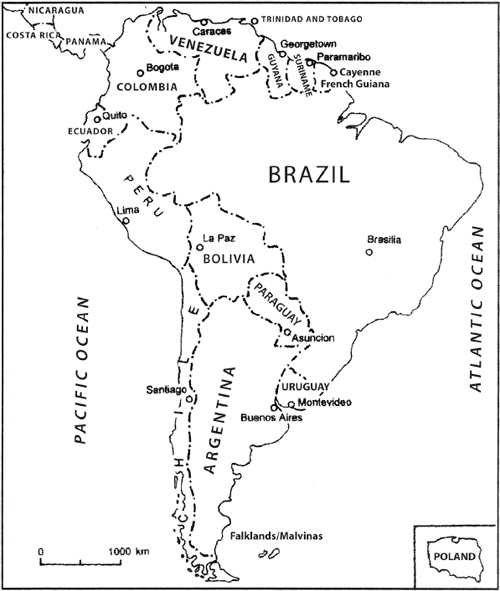

Map 1: Bolivia in Latin America.

← 11 | 12 → Map 2: Bolivia. Territorial division.

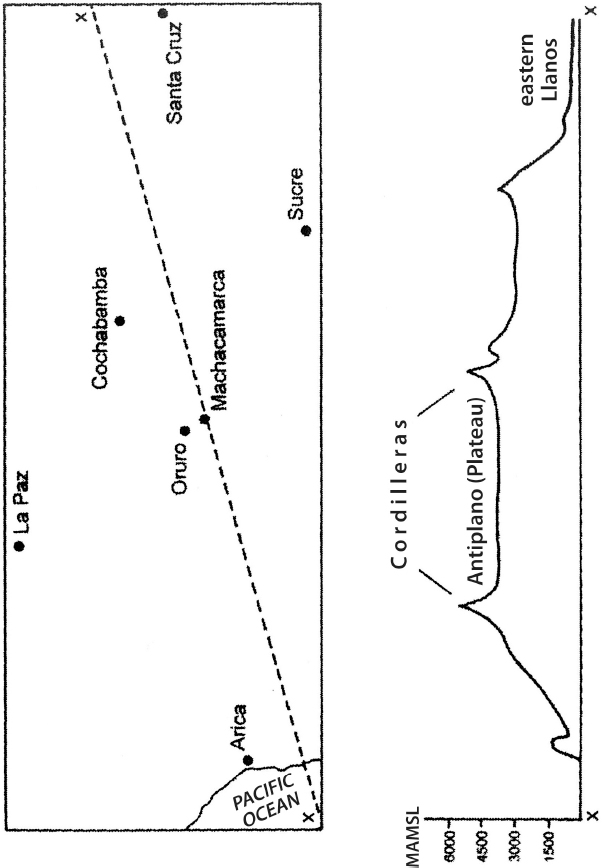

← 12 | 13 → Map 3: Bolivia. Vertical cross-section along the line x – x (source: Ch. F. Gaddes, Patiño. The Tin King, London 1972).

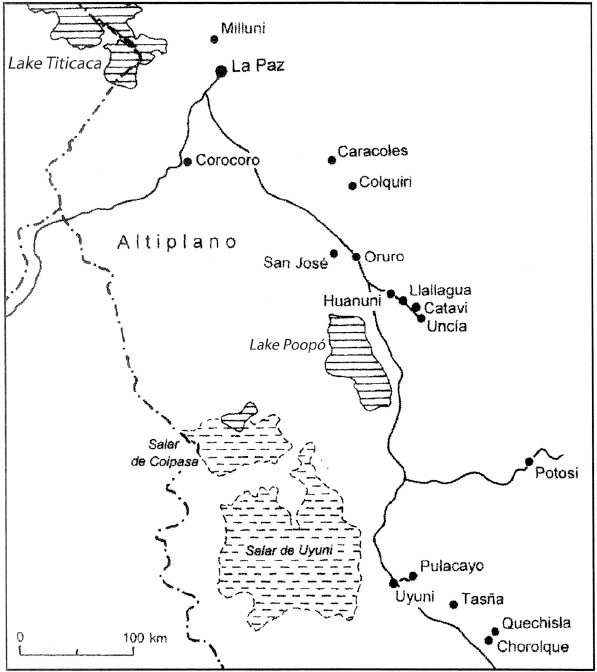

← 13 | 14 → Map 4: Bolivia. Selected mining centres.

← 14 | 15 → Chapter 1: Bolivia First!

For Bolivia, the 20th century began in 1932 with the outbreak of the war with Paraguay. It is impossible to give a more precise date, since there was no official inaugural shot.

The object of the conflict was the area known as the Chaco Boreal, which is the portion of the Gran Chaco to the north of the Rio Pilcomayo. The arid steppe region almost the size of today’s Poland, was at the time inhabited by a total of approximately 20,000 people including several hundred Whites. It had been disputed since the colonial times. The border had never been precisely defined. The exercise of sovereignty was rather theoretical; land was bought out just in case by people who resided far away; the local Indians, some of whom continued to live in nomadic tribes, were never even aware of the fact.

In the period in question, there was hope that large oil deposits would be discovered in the Chaco – and hence the area became valuable. When the war with Paraguay heated up, there were rumours that it had broken out because of the petroleum conglomerates. Standard Oil had significant investments in Bolivia at the time, while Royal Dutch Shell and various English and Argentinean interests were more closely allied with Paraguay. It was thus suspected that these companies were funding the war. This supposition became widespread not just in Bolivia but throughout Latin America. Even the young Cubans – far away though they were – wrote that the Bolivian students who died in the Chaco “were the victims of British and Yankee imperialism”5. After the war, no proof was found to substantiate these allegations, as was the case with oil deposits in the Chaco.

The reasons for this war cannot be explained away by referring to real direct interests – even though somewhere at the edge of the conflict there was probably competition between the United States and England for their position in Latin America and – most probably – between Argentina and the States for leadership in that part of the world. The first significant hostilities in the conflict that culminated in the Chaco War took place in 1928, when the Paraguayans launched a surprise attack, overrunning the Bolivian outpost of Fortin Vanguardia. The Bolivians responded by occupying several Paraguayan forts.

The transfer of the conflict onto the diplomatic plane (international mediation) delayed the start of hostilities somewhat. However, in July 1932 Bolivia ← 15 | 16 → occupied more forts in the Chaco – which Paraguay considered an act of war. On 1 August 1932, the Paraguayan parliament issued a decree for universal mobilisation, and on 10 May 1932 Paraguay formally declared war – which was already being fought anyway.

Bolivia was feeling that it was stronger than Paraguay and was probably militarily better prepared. It’s possible that its president, Daniel Salamanca (1931-1934) needed a “short victorious war” (to use von Plehve’s expression about Russia’s war with Japan) do resolve its internal problems. The country depended on exports of tin ores. However, by the 1920s his sector of the economy was already beginning to show signs of stagnation. The situation worsened with the onset of the Great Depression of the 1920s-1930s. In 1931 the price of tin fell to its historical low, causing Bolivia to suspend repayment of its foreign debt.

Bolivia was not alone in feeling the perturbations of the 1920s and the effects of the Great Depression, which strongly affected many Latin American countries, most of which had mono-export economies. Some of them experienced revolutions, in several others the governments collapsed. In Bolivia President Hernando Siles, who had ruled since 1926, was deposed in 1930 and a military junta took power. March 1931 saw the inauguration of President Salamanca who had to find a solution to the country’s problems – and found a solution of sorts, in the form of a war.

The Bolivian strategists turned out to be completely devoid of imagination. The combat zone lay far from the populated and economically developed areas of the country and had an underdeveloped transportation network. Everything had to be transported to the front from huge distances. It was said that in that war, for every front-line soldier two were needed in transport. It is true that at present the proportions are even more skewed but at the time the ratio was too large and proved fatal to Bolivia.

What is worse, the war also turned out to be difficult for Bolivia for other reasons. The terrain made large-scale use of cavalry or tanks impossible and proved very difficult for infantry as well. It was a war of heat, biting flies and thirst. Since many of the rivers, lakes and other natural bodies of water are saline, the most intense fighting was over sources of potable water, which frequently had to be replaced by cactus sap.

The Indians from the Bolivian Plateau who made up the majority of Bolivia’s army were not used to the hot lowlands where they had been dragged to fight. Because of Bolivia’s social structure, the Indian soldiers did not care much about the war of their white officers. Desertion was rampant.

The small Paraguay, on the other hand, turned out to be courageous, integrated, marked by a smaller degree of ethnic and class inequality, and its soldiers ← 16 | 17 → were at home in the combat zone. During 1926-1930 its army was trained by the French and later by the Argentineans. The Paraguayan commander-in-chief, Gen. José Félix Estigarribia, completed his military education in France and was considered a disciple of Foch. He was able to effectively confront the Bolivians who since 1911 had been receiving military training and support through the German embassy. A German officer, Col. Hans Kundt, had been Chief of Staff of the Bolivian army during 1911-1914, 1921-1926 and 1929-1930 before – having been promoted to the rank of general – he played a leading role in the Chaco War.

At least some outside observers expected Bolivia to be defeated. Mieczysław Lepecki, an explorer and expert on Latin America, recalled his conversation – although one he had later, in 1935 – with Józef Piłsudski, whose aide-de-camp he was:

In the evening, the Marshal asked me to say something about the war between Paraguay and Bolivia. After an hour-long conversation, he asked:

“And what do you think, who will win?”

“Paraguay, sir.”

“Well, well, aren’t you sure of yourself. Tell me, what makes you think that?”

I defended my opinion by pointing out that due to the mistakes made by the Bolivian command, the front was located in a remote area, too far from the Bolivian base of operations, and that the poor connections between the front and the base of supplies was the final argument in favour of Paraguay. Unlike the Bolivian forces, Paraguay’s army was operating relatively close to their base of supplies and were well connected with it.

The marshal, having listened to me, replied:

“If what you are saying about the connections between the front and the hinterland is true, then Paraguay will probably win.”6

And that is in fact what happened. In June 1935, when the armistice ending the war was signed, Bolivia was the clear loser. It had lost most of the disputed territory, which was confirmed by the peace treaty finally signed in 1938 (the countries already re-established diplomatic relations in 1936). The Chaco War claimed 52,000 soldiers, some of them dying in combat, others from thirst or as a result of drinking the first water they found which proved to be tainted. The country’s budgetary situation was catastrophic and inflation had radically reduced the value of its currency.

← 17 | 18 → The feeling of defeat was exacerbated by a factor of humiliation. This was due to the fact that the Paraguayans had taken more Bolivian prisoners of war than the Bolivians (32,000 vs. 3,000)7. Paraguay used the Bolivian POWs to perform farm work and was in no hurry to release them and what is more, it demanded payment for their upkeep. Bolivian public opinion was outraged. Paraguay finally returned the prisoners in 1936-1937 but Bolivia agreed to pay a significant amount for their upkeep. In addition, when setting the armistice line, for a long time Paraguay did not want to offer any concessions – even ones whose only effect would be letting Bolivia save face. The peace treaty, signed with the assistance of Argentinian Foreign Minister Carlos Saavedra Lamas (who received the Nobel Peace Prize) and at the express wish of the United States to end the whole conflict did not even award Bolivia a port on the Paraguay River which would have given it access to the Atlantic and the world. It can also be recalled that the League of Nations, which considered the Chaco War, did not prove effective in stopping or ending the conflict.

Equally important is the fact that the lost war embarrassed both the state and its army. President Salamanca, who went to the front in 1934 to dismiss the commander of the army, General Enrique Peñaranda del Castillo was arrested by the troops. He was replaced by his vice-president, José Luis Tejada Sorzano. However, General Peñaranda came to be viewed as the symbol of all that was evil. There appeared among the public the motif of confronting the image of dedicated soldier with that of the corrupt politicians and ineffective – if not treasonous – commanders.

The return of the General Staff led by General Peñaranda from the Chaco to La Paz in the autumn of 1935 did not turn out to be a national celebration. Several hours earlier, civilians had been prevented from approaching the train station, and machine guns were placed on the roofs of buildings. The general came to the presidential palace protected by a fully-armed cavalry unit whose officers were selected from among the most trustworthy. The crowd gathered in front of the palace was initially silent but then parts of it started began to whistle and jeer.

The first Bolivian prisoners returning from captivity in May 1936 received a much warmer welcome. “This was the first occasion during the twelve months I have been here that the people showed any signs of enthusiasm,” wrote a witness8. The Bolivian establishment was fearful of these people’s return.

Details

- Pages

- 316

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631653234

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653045000

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653983517

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653983524

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-04500-0

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (June)

- Keywords

- Bolivian revolution of 1952 Indians in Bolivia agrarian reform Bolivian intellectuals

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2015. 316 pp., 4 b/w fig.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG