South Asia and Disability Studies

Redefining Boundaries and Extending Horizons

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface

- References

- Acknowledgments

- About the Cover Artist

- A Note on Language and Terminology

- Section I: Introduction

- Chapter 1: South Asia and Disability Studies: Time for a Conversation

- Tensions and Possibilities

- Considering a Reciprocal Relationship

- Situating the Conversation

- Section I: Introduction

- Section II: South Asia Disability Policy

- Section III: Understanding Historical and Cultural Contexts of Disability in South Asia

- Section IV: Identity and Constructions of Disability in South Asia

- Section V: Conclusion

- References

- Chapter 2: Charting the Landscape of Disability Studies in South Asia

- Disability Studies: Tracing the Roots

- The Social Model of Disability

- The Social Constructionist Model of Disability

- Postcolonial Theory and Disability Studies

- Disability Studies, Disability Studies in Education, and South Asia: Origins and Debates

- Transfer of Western Special Education Discourse and Technology

- Cultural and Indigenous Interpretations of Disability

- Disability and Development

- References

- Section II: South Asia Disability Policy

- Chapter 3: Mind the Gap: Special Education Policy and Practice in India in the Context of Globalization

- The Context of Globalization

- The Contextual Gap

- The Temporal Gap

- Globalization and Educational Systems

- Emphasis on English as a Medium of Instruction

- The Use of Universal Standards for Assessment

- The Consequences of Not Minding the Gap

- References

- Chapter 4: The Terrain of Disability Law in Sri Lanka: Obstacles and Possibilities for Change

- Disability in Sri Lanka

- Global Contexts

- Law in Sri Lanka

- Fundamental Rights (Chapter III)

- Disability Law in Sri Lanka

- Frameworks

- Protection of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (No. 28 of 1996)

- A Disability Rights Bill and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- Legal Mobilisation and Public Interest

- Conclusion

- Note

- References

- Chapter 5: Gender Sensitivity in Disability Initiatives: Perspectives on South Asia

- Disability and Gender

- Women with Disabilities in Asia

- Poverty and Women with Disabilities in Asia

- Gender and Disability in Development

- Empowerment of Women through Program Activities

- Disability Awareness

- Socioeconomic Empowerment

- Rights and Advocacy

- Health Promotion and Rehabilitation

- “Fixing” the Disability

- Implications for Women with Disabilities in South Asia

- Employability and Vocational Rehabilitation

- Structural Exclusion

- Barriers to Accessibility

- Integrating Disability in Women’s Agenda

- Women with Disabilities in Development

- Caregiving

- Conclusion

- References

- Section III: Understanding Historical and Cultural Contexts of Disability in South Asia

- Chapter 6: Studying Responses to Disability in South Asian Histories: Approaches Personal, Prakrital and Pragmatical

- Introduction

- Targets and Near-Misses

- Dodging Cross Disciplinarians?

- Soothing the Critical Tendency

- Casting Forth Demons

- Disability Historiography

- Reciprocal Viewpoint?

- Interpretation

- Bite-Sized Chunks

- Modest Conclusion

- Acknowledgment

- References

- Addendum in 2013 to Chapter 6

- References

- Updated URLs

- Chapter 7 Corporeality and Culture: Theorizing Difference in the South Asian Context

- Problems of Concept, Questions of History

- Toward a Reconceptualization of Corporeality in Non-Western Contexts

- Sitala

- Affect and Corporeality

- Giving, Detachment, and the Corporeal

- Space and Corporeality

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter 8: Colloquial Language and Disability: Local Contexts and Implications for Inclusion

- Discourse on Disability Labels and Nomenclature in the North

- Discourse on Disability Labels and Nomenclature in the South

- Method

- Findings

- “Inconvenience” in the Colloquial Form

- Disability as an “Inconvenience”

- Colloquial Language and Varying Interpretations of Intelligence

- Discussion

- References

- Section IV: Identity and Constructions of Disability in South Asia

- Chapter 9: Disability, Gender and Education: Exploring the Impact of Education on the Lives of Women with Disabilities in Pakistan

- Women with Disabilities in Southern Context—An Overview

- Disability in Pakistan

- Developing a Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Lives of Women with Disabilities

- Research Methodology

- Educational Profile of Women with Disabilities

- Educational Experiences

- Educational Outcomes

- Discussion

- Understanding Educational Outcomes through a Capabilities Lens

- Acknowledgments

- References

- Chapter 10: “Just a Member of the Neighborhood”: Bengali Mothers’ Efforts to Facilitate Inclusion for Their Children with Disabilities within Local Communities

- Inclusive Education: Global and Local Discourse

- Building Ties of Affection

- Building a Relationship with the Children

- Encouraging Ties of Affection Amongst the Children

- Providing a Context to Bring the Children Together

- Fighting Street Battles

- “I Spoke to Goutom’s Conscience and Not Goutom!”: Evoking the Humaneness in People who Exclude

- “Tell Me Who is Really Abnormal Here?” Challenging Labels

- The Neighborhood as a Family

- “He is the Son of a Cultured Man”: Evoking a Valued Status

- Discussion

- References

- Chapter 11: Disability and Modernity: Bringing Disability Studies to Literary Research in India

- Being Animal, Becoming “Disabled”

- Modernizing Disability Subjectivity

- Narrating Disability

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter 12: Body, Behavior, Boundaries, and Belonging: Disability in Contemporary Bollywood Films

- Bollywood Films and Disability Images

- A “Guzaarish” (Request) for Euthanasia

- The Disabled Body as a “Cage”—Visual Rhetorics and Enshrining the Able Body

- Whose Voice is it Anyway?

- A Discourse on “Euthanasia” in an Amorphous Cultural and Social Narrative

- My Name is Khan

- Bollywood and its Gaze on the Autistic Body and Behaviors

- Autistic Savant and Narrative Prosthesis in My Name is Khan

- Conclusion

- References

- Section V: Conclusion

- Chapter 13: Conclusion

- What are the Notions and Language of Disability in South Asia?

- What Analytical Lenses to Use?

- Who Conducts the Research?

- How is the Research Being Conducted and Presented?

- What is the Significance of This Research?

- References

- Contributors

- Index

- Series index

← viii | ix → Preface

We are both South Asian women with an interest in the area of culture and disability in general and disability within the Indian context in particular that has extended over decades. Our interest in this area began with our experiences as teachers of children with moderate and severe disabilities in India in the early 1980s and has continued as researchers through the years. As teachers, we challenged the circumscribed curriculum and the low expectations for children with disabilities that were reflected in instructional approaches and the labels assigned to the children. We struggled against perceptions that we were teaching pagal (crazy) or langda (lame) children, even as the government introduced the official, virtually unknown and, therefore interestingly, neutral term of vikhlang for disability. We were intrigued by the assumption that segregated settings were somehow considered to be the inevitable place for many students with significant disabilities despite the increasing emphasis on inclusion reflected in educational policy. Over the years, we were struck by how, in the absence of services, many children who, in the 1980s, were absorbed by the educational system, now are labeled “mentally retarded,” “dyslexic,” or “autistic” and often receive services in separate settings. In the absence of indigenous descriptors, these labels were imported directly from English in the insouciant assumption that their meanings would transfer unconditionally. So began our introduction to the language of disability, the arbitrariness of the labeling process, and the “othering” that resulted from the development of services intended to promote inclusion.

In our work as teachers and as researchers, we also noticed that socioeconomic status appeared to play a major role in parent participation. Most of the parents who were involved in developing services, establishing parent associations, or were themselves engaged as service providers were of the middle class. There were few services that targeted low-income families, and those that did tended to see parent participation more in terms of training parents to be, as it were, better parents for their child with disabilities. Yet our research suggested that, even though the consolidation of their status as ← ix | x → migrants to the city from rural areas was a main priority for low-income families, they were articulate about their concerns for their child or young adult and, in many cases, were not hesitant about seeking the appropriate supports to ensure that their child was included within the social fabric of their lives. We also noticed the striking contrast between the families’ strengths-based perceptions of their child and the deficit-oriented constructions implicit in professionals’ labels. We observed parents’ concerns about vocational opportunities for their young adult with disabilities whereby many middle-class families preferred to look within their circle of extended family and friends for jobs that were suited to their socioeconomic status, while many low-income families chose to keep their young adult daughters at home rather than risk her safety working outside the home. This intersectionality of class, sometimes linked with caste in India, and gender with disability made us aware of the complexity of the concepts of disability and parent participation as played out in the lived realities of families.

We brought this experience and knowledge with us when we arrived as graduate students in the U.S., hoping to learn from a country that had already progressed far beyond existing policy and practice in India, and we were surprised to find that the models that prevailed in the U.S. had little applicability to the current context in India. Whereas in the U.S. in the mid-1980s, group homes were being hailed as the new frontier for people with disabilities who had been institutionalized in what were, for many, inhumane conditions, the absence of a historical legacy of institutions and the efforts of families to create spaces of inclusion for their children within the relational network that we had witnessed in India suggested that group homes would be completely out of place in a South Asian context. Even as we learned about the principle of normalization that sought to identify the “normal rhythms of life” and ensure inclusion in the community for children and adults with disabilities, we wondered: normal to whose imagined community? Once again, we were made aware of the strong underpinnings of historical, cultural, political, and social contexts imbedded in special education practice and policy and in constructions of disability.

Our approach as researchers has been influenced predominantly by the social constructionist model of disability. We view disability as a construct or a creation that can be understood only in the specific cultural or social context within which it is situated (Taylor, 2008). We found our training in qualitative research to be a powerful tool to help understand how disability is understood and interpreted in the Indian context. Our prior work with the ← x | xi → Indian context of special education has focused on how families interpret and understand disability, how schooling is experienced by children with disabilities and their families, particularly from low-income backgrounds, how policy reflects both implicit and explicit constructions of disability, how colloquial language is used by families to navigate social reactions to disability within the community, how families define and challenge traditional notions of normalcy, and how they attempt to create inclusion. Our work in the U.S. has focused on the perspectives of culturally diverse families of children with disabilities, construction of disability in educational policies, and inclusive education. Similar to our journey as teachers in India, our work as scholars in the U.S. has further underscored the contextual underpinnings of disability. In our journey, we have come to agree with the disability studies perspective that while impairment exists everywhere, the interpretation and construction of disability differs (Barnes, Oliver, & Barton, 2008). To us, this means that the notion that constructions of disability are universal stands on tenuous grounds. Our early roots in the social constructionist approach and our work with culture and disability have significantly furthered our interest in the field of disability studies, the current interdisciplinary/intersectional conversations in this field, and the implications for disability studies within the South Asian perspective.

It has been exciting for us to watch this fledgling field come into its own as the significant contributions of other South Asian scholars on disability studies have grown. Understanding disability within South Asia from the disability studies approach requires examining the shifting interpretations of disability that come with increasing globalization, identifying the meanings ascribed to the disabled body and specific disability-related constructs such as “mental retardation,” and deconstructing the portrayal of disability in cultural narratives within South Asia. This book has been organized in a way so as to ensure an integrated and cogent sampling of works ranging from the examination of structural factors to historical and cultural factors framing the disability experience in South Asia. The organization of topics parallels the discourse in different areas within disability studies such as identity construction, language, historical constructions of disability, cultural representations of disability, etc. The chapters in this volume present an eclectic mix not only in terms of the specific disciplinary areas within disability studies in South Asia that they sample but also in terms of the disability studies strands that they originate from or align with. We hope that ← xi | xii → this book precipitates a deeply engaged and more sophisticated analysis that emerges from a reciprocal discourse and expands the current theoretical frameworks within disability studies.

Shridevi Rao

Maya Kalyanpur

December 2014

References

Barnes, C., Oliver, M., & Barton, L. (2008). Introduction. In C. Barnes, M. Oliver, & L. Barton (Eds.), Disability studies today (pp. 1–17). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Taylor, S. (2008). Before it had a name: Exploring the historical roots of disability studies in education. In S. Danforth & S. Gabel (Eds.), Vital questions facing disability studies in education (pp. xiii–xxiii). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

← xii | xiii → Acknowledgments

It takes a village “they say” to raise a child. It also takes a village to support an endeavor like this. We are deeply grateful to each of our wonderful authors whose contributions helped redefine the boundaries and extend the horizons. It has been an absolute pleasure working with you on this journey. Many thanks go to our Series Editors, Susan Gabel and Scott Danforth, for their insightful comments and support through this process and the team at Peter Lang for all their assistance. A special thank you to Ellen Farr for her meticulous and painstaking work with typesetting the manuscript. Much gratitude also to Adarsh Baji for the cover art. Thanks to my lifelong friend and intellectual mentor, my dad, Mr. Arkalgud Subba Rao. I could not have done this without your unwavering support, steadfast belief, and thoughtful feedback. Here is to our countless great conversations, conversations that set the stage for this book. I wish you were here to see the book but I know, wherever you are, you are smiling. I thank my son Tejas Srinivasan for reading the first drafts of some of my chapters. Your encouragement, astute feedback, and faith in my work kept me going. Thanks to my husband Sivaram Srinivasan and daughter Sarayu Srinivasan for patiently putting up with me throughout this process, for the smiles, numerous cups of tea, and loads of encouragement. You are amazing! Thanks to my mother Subhadra Rao, sister Shailaja Rao, and brother Satya Rao for their constant support through this process and my in-laws Mr. & Mrs. Srinivasan. And finally, much gratitude to my co-editor and friend Maya Kalyanpur. It has been a pleasure to have you as a partner through this journey. Could not have done it without you!

Shridevi Rao

I thank my faith-keepers, my husband, Vijay Rao, my son, David Rao, my sister, Sona Kalyanpur Rao, and my friend and colleague, Beth Harry, who continue to amaze me by their willingness to stand by me. I would like to acknowledge Shridevi Rao, co-editor, co-author and friend, who has contributed a great deal to my thinking on this topic over the past so many ← xiii | xiv → years. Your hands at the small of my back and unconditional love have given me the strength and confidence to start over, and over, and over. Much gratitude to the Towson clan, Mala Mathrani, Mubina Kirmani, and Suman and Bindu Noor, for their enduring friendship and for helping me to dance again.

Maya Kalyanpur

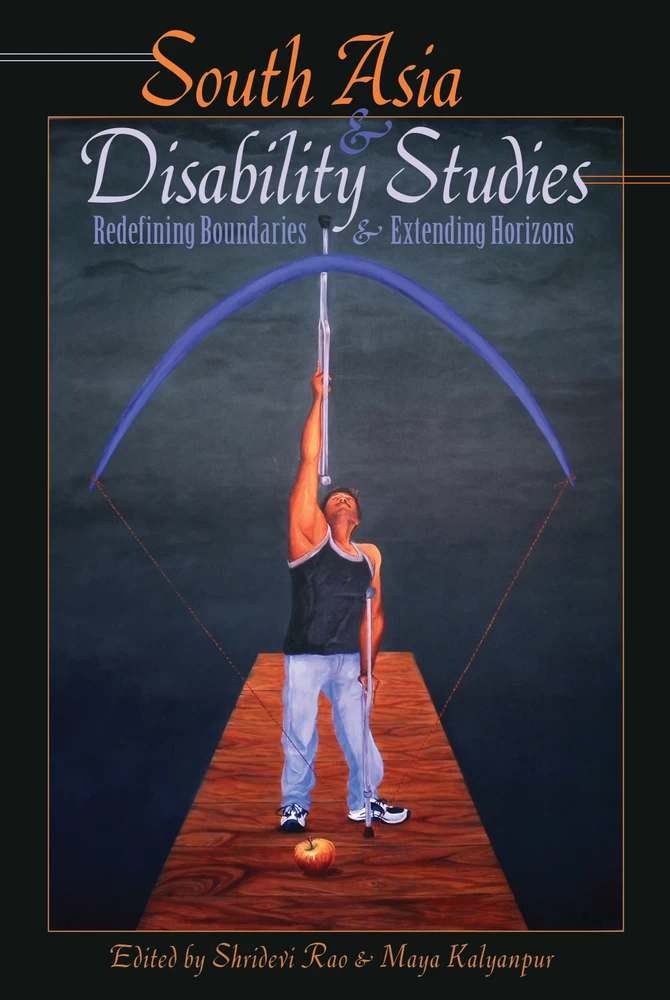

← xiv | xv → About the Cover Artist

The cover is a photograph of an original work of art—The Visioner—created by Adarsh Baji. Mr. Baji is an award-winning artist in Baroda, India, and identifies himself as a disabled person. His artwork has been exhibited in various prestigious national and international forums including M.S. Univerity Baroda, Coomaraswamy Hall Museum of Western India in Mumbai, Exhibition of Contemporary Indian Print Making Art at Wharepuke, New Zealand, and the Ahmedabad International Arts Festival. His paintings are provocative and offer nuanced, layered and metaphorical interpretations of the disabled experience. His interpretation of The Visioner is as follows:

In this painting, my intention is “don’t think I’m a weak person, if you have a chance, search for my strength & power. I’m also a son of God, God how He made you, He made me also like this. (If) you can use me in the right way, I’ll be like a weapon. I’ll reach a goal and target. I’m useful for society, don't neglect me. Every person is unique in this world, just search (for) his inner strength.” In this painting, I put one apple in front of me. Symbolically, this apple is temptation (like in the Bible, the garden of Eden story). In a disabled person’s life, they will get lots of temptation; e.g., somebody showing sympathy, somebody giving help, government giving reservations, etc. These are all small, small things in our life. “Don't get tempted by this, don’t bend yourself. You have power; you can choose your target. One day, you will get success; you will reach your target.”

Mr. Baji’s artwork can be accessed at http://adarshbaji.weebly.com. ← xv | xvi →

← xvi | xvii → A Note on Language and Terminology

The language and terminology used to denote disability have undergone significant shifts over the last few decades. No longer is the issue of terminology merely a choice of technicalities; it is inextricably linked to notions of identity, humanity, and personhood. However, at the same time, it is also an issue fraught with contradictions. The discourse on language within the US has favored the use of Person First language such as “people with disabilities.” Many disability rights advocates as well as scholars in the US have acknowledged this convention as one that recognizes the humanity and unique identity of the individual first and then the disability. However, the discourse in the UK has tended to favor the use of the term “disabled.” Rooted within the social model, the conversation on disability semantics in the UK has drawn attention to the need to consciously adopt language that underscores the ways in which disability is created through the systemic exclusion and oppression of people with disabilities through policies and practice. The term “disabled” is preferred as it puts the onus for the construction of disability squarely on society and societal practices. In contrast to the way this term is viewed within the US, the use of the term “disabled” is not seen as one that communicates disability as a characteristic that is intrinsic to the person. Furthermore, recently, the neurodiversity movement in the US has called for the celebration of the identity of disability. Thus within this context, some self-advocates with autism reject Person First language and choose to define themselves as autistic. They argue that autism is a part of human diversity and recognizing or presenting oneself as autistic is a means of embracing an identity that is imbedded in this diversity. Meanwhile, while much has transpired in the area of semantics and disability in the North and the conversations about terminology and their implications have continually shifted, conversations about terminology in South Asia bring up new quandaries. Whose terminology should we use? Do terms that have evolved with unique contextual roots in the UK or the US have the same connotations or implications for South Asia? How should we even approach the issue of language for a collection that focuses on the ← xvii | xviii → disability experience in South Asia when the discourse on language is emerging?

The contributions in this book represent varying contextual roots of disability studies terminology. Some of the contributors use Person First language or preface the term “disability” with qualifiers such as “labeled as.” Others use the term “disabled” as prevalent in the discourse within the UK. The term “autistic,” with its underlying implications for identity as prevalent in the current discourse, has also been used in some instances. Terms evolving from the medical model such as “mental retardation” are cited only in a context where participants or documents in a study refer to that language. Some contributions draw attention to indigenous language, which may present unique challenges in finding equivalent translations in English. The implications of these indigenous terminologies have been explored and examined. Our efforts have been to encourage the use of terminologies in a conscious, thoughtful, and reflexive way while being cognizant of the social, cultural, and contextual roots.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 311

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433119101

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453913536

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454191568

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454191575

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433119118

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1353-6

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (December)

- Keywords

- poverty education employment sociology historiography

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2015. 311 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG