Tweening the Girl

The Crystallization of the Tween Market

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Permissions

- 1. Introduction

- Defining the tween girl

- 2. “Discovering” the tween

- Shifting definitions of childhood and adolescence

- Childhood and adolescence in twentieth century consumer culture

- The mediated marketplace

- The tween girl as a commercial persona

- Defining personae

- The functions of commercial personae

- The circuitry of the mediated marketplace

- Doing the research

- Historical case study of crystallization

- 3. Girls just wanna have fun

- The renaissance of the girl

- The girl and teen culture

- Referencing girl subjectivity

- Feminism and the girl

- Feminism trivializes the girl

- Feminism “discovers” the girl

- Popular culture and feminism

- Conclusion: celebrating girlhood

- 4. Selling the in beTween

- Selling the in beTween: Commodifying transformation and transition

- Before the 1980s: Tracing the beginnings of the tween girls’ market

- Commodifing puberty

- Solving the riddle of the preteen

- The liminality of becoming

- BeTween in the school system

- Consumption and the feminine

- The tween as a female consumer

- Conclusion

- 5. Momma’s little shoppers: Upaging the child

- A history of the children’s market

- The changing mediascape

- Deregulation

- Kids getting older younger

- Loss of innocence

- Consumer socialization

- Feminism and the changing family

- Discovery of the tween

- The liminality of the upaging

- Conclusion

- 6. Selling cool: Downaging the teen

- The history of the teen market

- The expanding mediascape

- Expanding the boundaries of the youth market

- Downaging the teen

- Selling the value of the youth market

- Forging loyalty

- Teenaging culture

- Conclusion

- 7. Conclusion

- The Feminist Connection

- The new tween

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

This has been a long and tedious process throughout which I had much support. Like every great accomplishment this could not have been done without the encouragement of all of my loved ones. There is a little piece of all of you in this work.

On a personal level, I would like to give a heartfelt thanks to my parents Marie and Ken who have supported me in ways too numerous to count. I am so blessed to be their daughter and would never have started this journey without their love and guidance. To my incredible husband Troy who has put up with this project being in my life for a long time, and has encouraged me and loved me at all times, especially when I didn’t believe in myself. To my sister Lorna who has always been there with an encouraging word and my amazing Aunt Cathy who has supported me in many ways including coming through with some last minute editing. My Uncle Cecil would have loved to have seen this finished, as too would my parents-in-law Bev and Tom. I miss you all dearly and I know you would all be proud. Thank you to all of my extended family who have encouraged me and taken an interest in this project over the years. I also want to thank all of my friends who cheered me on and supported me in a myriad of ways including providing me with workspaces, looking after my daughters, listening to me whine, taking me out for wine and always being there for the belly laughs; Dorie, Amanda, Karen, Steph, Sue and Jay, Victoria, Courtney, Shelley, Laurel, Tom and Cath, and all my neighbours on Currie Ave. Thank you for never saying “aren’t you done with that thing yet?” but instead offering your support. ← ix | x →

Professionally, I owe a tremendous amount of gratitude to my dedicated advisor Stephen Kline who supported this project from the beginning and continues to support me in my academic career. As my advisor Steve was able to provide the delicate balance between guidance and stepping back trusting that I could figure it out myself. Steve along with my other committed advisor, Catherine Murray, provided much invaluable advice and encouragement over the many, many years of this project. Also I would like to thank those who were part of my dissertation examination and provided vital insight into this project, Dawn Currie, Zöe Druick and Özlem Sensoy. I must also acknowledge the enormous support of many friends and colleagues in the departments of Communication Studies at York University, at Wilfrid Laurier University and at the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University. I also would like to thank the Faculty of Liberal and Professional Studies, York University, for the financial support it provided this work.

To my academic colleagues and friends, Gillian Parekh, Christine LeNouvel, Mark Ihnat, Ian Roderick, Tracy Jenkin, Rhiannon Bury and Anne Marie Kinahan who have all provided a sympathetic ear when I most needed it and to my confidants in my writing group Graduate Students Group 3, who ended the loneliness of this process, I thank you. I also must thank the strong, articulate and thoughtful women who I interviewed for this book. These women took time out of their busy lives, opened up, provided honest answers, and waited and waited for a final product, I thank you.

I also must thank the wonderful team at Peter Lang who have made this process of being a first time author incredibly easy and smooth; my editor Mary Savigar and the series editor Sharon Mazzarella whose validation in the quality of my work in this book have given me great strength. Their insights along with Jackie Pavlovic’s guidance have helped steer this book to completion. And thank you to Jennifer Etches for her stellar photography, and all the girls in the photo, Maeve, Giselle, Macie, Hannah, Isla, and Pam.

Finally I must thank Maeve and Cambie who came into my life at various stages of this project. They have both given me so much; they have provided me with focus, perspective, distractions and joy during the many stages of this project. And a special thank you to Cambie who as an unborn baby gave me the final push to finish this thing.

Permissions

Coulter, N. The Consumption Chronicles: Tales from Suburban Tweens. Seven Going on Seventeen. Claudia Mitchell and Jacqueline Reid-Walsh, editors, Peter Lang (2005). Reprinted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ← x | xi →

Coulter, N. Selling Youth: Youth, Media and the Marketplace. Mediascapes. 3rd edition. Paul Attallah and Leslie Regan Shade, editors, Nelson Education. (2009). Reprinted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ← xi | xii → ← xii | xiii →

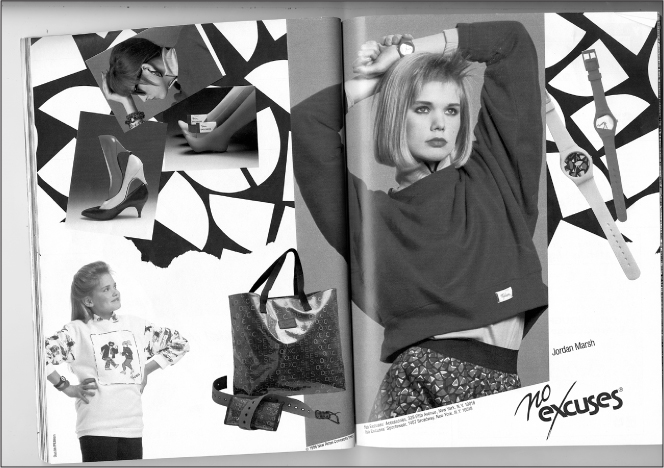

No Excuses advertisement from Seventeen Magazine (August 1986), pages 50–51 © 1986, No Excuses Sportswear Ltd.

← xiii | xiv →← xiv | 1 →On July 8 1996, the Spice Girls released ‘Wannabe’ and with it a new pre-teen generation was born.

—RICE, 2000

In the summer of 2012, I like virtually everyone else in the world was glued to the TV watching the closing ceremonies of the London Games. For weeks leading up to the ceremonies there were rumours of a Spice Girls reunion. The energy of the crowd in anticipation of the Girls was palpable even from my couch in my little living room half the globe away from London. True to form, when the Spice Girls did appear, rolling into the stage stadium precariously perched atop bejewelled London taxi- cabs, they brought the house down. I have always had a mixed reaction to the Spice Girls. When I had first learnt about the Spice Girls in the mid-1990s, my response was utter indignation. I mean who were these garishly clad women dancing around in sequin micro-minis and platform boots calling out to us to “Spice up [our] life”? My indignation was pushed even further when I found out that they had these ridiculously insipid stage names, like Posh Spice, Scary Spice and, even worse, Baby Spice. Nevertheless, once I became familiar with them, their anthem of Girl Power piqued my feminist sensibilities. Rarely had I heard such an overt declaration for equality. And there was a third response. While wrestling with my conflicted views, I could not help but smile and bop along with their catchy music on the radio. ← 1 | 2 →

But none of this really mattered to the band as I was not the chosen demographic of the Spice Girls audience. Being in my early 20s, I was much too old to be of consequence to the growing Spice empire. The phenomenal success of the Girls lay in the hearts and wallets of the millions of devoted pre-pubescent girls who lined up for hours to buy tickets to their concerts, concerts which sold out in minutes. These girls bought their albums at unprecedented rates, over 55 million albums worldwide, and sent the Girls to the top of the Billboard charts in over 31 countries, becoming the fastest-selling musical act since the Beatles (Sinclair 2004). And it did not stop there. These same girls bought all things Spice; stickers, dolls, lollipops, backpacks, notebooks, each item emboldened with messages of “Girl Power”. Ultimately, it was these girls who had the power to make the Spice Girls a commercial success.

The Spice Girls phenomenon awoke the world to the incredible commercial power of the girl consumer who became knows as a tween. In turn, it helped launch a campaign that solidified the tween category in the public conscious. The power of the Spice Girls was noted by Karen Brooks, spokesperson for the accessories retail chain Claire’s, who stated that with the release of their first album Wannabe in 1996 the “appearance of Sporty, Scary, Ginger, Posh and Baby unleashed a tsunami of genuine wannabes—a generation of little girls with money and aspirations, just waiting for a focus” (as quoted in Rice, 2000).

Since the Spice Girls, the tween phenomenon has flourished with ex-Mouseketeers Britney Spears and her rival Christina Aguilera, whose music dominated the pop charts in the late 1990s, followed by Hilary Duff who made the Forbes list of richest young stars under 25 in 2005 by flogging her clothing line, Stuff by Duff, alongside her movies, concerts and albums. The power of the tween star continued into the twenty-first century with the rise of Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen (MKA), a $1 billion-a-year global empire selling everything from phones to toothpaste to action dolls (Leith 2006, 57). Following MKA tween princess Miley Cyrus and her alter ego Hannah Montana dominated the marketplace with a clothing line, a record-breaking sell-out concert tour and, “to the [movie] industry’s astonishment,” a 3D film of her concert tour which made $31 million at its box office opening weekend (Dent 2008). The current titan of the tween is perhaps Justin Bieber with over 8.3 million song downloads, 2 billion YouTube views and 47 million Facebook fans. His concert sales for his latest concert alone are close to 85 million dollars, the box office take of his biopic Never Say Never is close to $100 million and his top song, “Baby,” spent 317 weeks on the charts.1 His influence is so extensive his young female fans are called “Beliebers”.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 191

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433121753

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453912447

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454199908

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454199915

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433121760

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1244-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2013 (July)

- Keywords

- adolescence childhood trade

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 191 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG