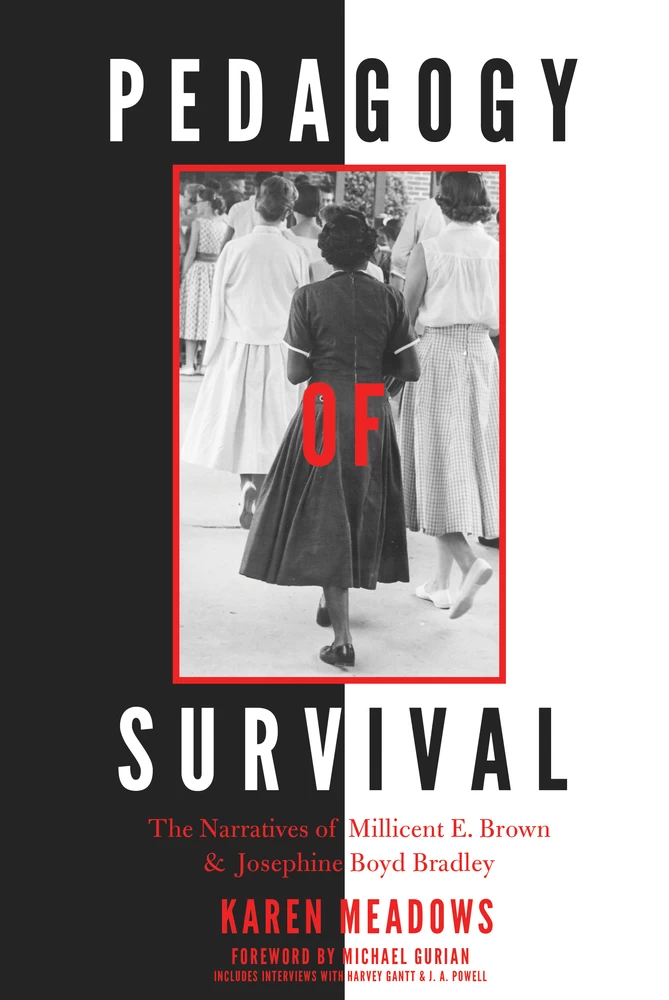

Pedagogy of Survival

The Narratives of Millicent E. Brown and Josephine Boyd Bradley

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Pedagogy of Survival

- Purpose of This Book

- The Methodology

- Chapter 1. The Desegregation of Rivers High School

- The Story

- The Groundwork

- A Turning Point

- The Trauma and Pedagogy of Survival

- The First Day

- Opposite the Front Door

- The Trauma

- Being Bullied

- Alienation

- Stress and Somatic Disturbances

- Pedagogy of Survival: The Intellect

- The Precedence for Her Pedagogy

- Buffered by Intellect

- The Teachers

- Blame, Guilt, and Responsibility

- Pedagogy of Survival: The Tragicomic

- Pedagogy of Survival: The Tiospaye

- Be Bigger

- Father

- Mother

- Sisters

- Conclusion

- Salute to Millicent Ellison Brown

- Chapter 2. The Desegregation of Greensboro (Grimsley) Senior High School

- The Story

- Dissension and Departure

- The Trauma and Pedagogy of Survival

- The First Day

- The Power of Counternarratives

- Counternarratives as Authentic Voice

- Counternarratives as Historical Contradictions

- The Trauma

- Hate and Pain

- Why Did They Do It?

- The Chosen One

- No One Ever Asked Me

- The Psychological

- The Isolation

- Pedagogy of Survival: Educational Schizophrenia

- Pedagogy of Survival: Faith, Family, and Community

- Hero Behind the Hero

- Faith and Family

- Mother and Father

- Three of the Seven

- Pedagogy of Survival: The Empathetic Practice of Peers

- Conclusion

- The Homegoing

- Salute to Josephine Ophelia Boyd Bradley

- Chapter 3. Pedagogy of Survival: Ordinary People with Extraordinary Lessons

- Pioneers Can’t Expect to Feel Normal: The Narratives of Harvey B. Gantt

- Entering through the Back Door: The Narratives of Dr. Larry Canady

- It’s Okay to Cry: The Narratives of Kristina Frazier

- Chapter 4. The Relevance

- Organic Intellectuals

- What Is an Organic Intellectual?

- Desegregation Pioneers as Organic Intellectuals

- Humility and Nonexceptionality

- Us, We, Me

- Insurgency

- Two Fronts

- The Organic Intellectual: Why Is This Concept Important?

- Implicit Bias

- What Is Implicit Bias?

- Awareness

- Priming

- Implicit Bias: Why Is This Concept Important?

- Donations

- Photos

- References

- Index

- Series Index

My thanks and gratitude, to so many, surpass written words, for the heart speaks its own language. However, it is the written word that I have as a communication tool and I hope these few words provide a glimpse into the impact you have made on my life. This book has been a labor of love, a test of endurance, an acknowledgment of those who have served as change agents, and a testimony to those who were willing to share their story and thus their pedagogy of survival.

I first thank and acknowledge God, my higher power, for directing me on this path. Thank you to my mother (Essie Mae Meadows) and my aunts (Catherine Meadows Thompson and Edith Morehead Davis), you have given me the faith, courage, and foundational supports I need to conquer any dream. Thank you to my cousin, Janine Davis, for being my best friend, confidante, and cheerleader. I appreciate you using your skill of read aloud to assist me with this book and thank you for building my confidence through my work with Girl Talk Foundation Inc. Thank you to my Greensboro and Miami family, especially my immediate family: Uncle Sonny/Robert Meadows (Rest in Peace), Susan and family, Omar (Rest in Peace), Marsha and family, Laurissa and family, Mitch, Terri, and family, and Kayla—thank you for sharing your teen perspective. Thank you to my friends whose support, concern, and belief ← xi | xii → in me made all the difference: Felicia Bowser for everything, from the use of your computer to the adjectives I needed from time to time to feeding this overworked author, I so appreciate you. Thank you to Yolanda Tate for the early years; I will never forget your support and ready-made dinners as I wrote my dissertation. Thank you to my “crew,” Donyell Roseboro, Sabrina Ross, and Tracey Snipes (Rest in Peace); your friendship during my doctoral journey was priceless and remains priceless today. Thank you to Hershela Washington and William Beatty “Big Will” (friends for over 20 years), Debbie Page and Donneka Byrd, your friendship means the world to me. Thank you to Renee Evans for being a listening ear, your story of Burt (the editor) and Bert (your grandmother) served as an impactful and life-changing testimony.

Thank you to Dr. Craig Peck for taking the time to read my work when I felt like giving up—your statement “I am proud of you” meant more than you know. Thank you to Jean Rohr who insisted, when I shared both my interest and fear about obtaining a doctorate degree, that I sit in on one of her doctoral classes—you have been a great model. Thank you to Dr. Kathleen Casey, my dissertation advisor, for spending countless hours reading and rereading my dissertation drafts. Thank you for teaching me the art and importance of narrative research.

Thank you to Cecil Williams, award-winning photographer, for your graciousness; it was an honor to speak with you. Thank you to Liz Foster, of the Post and Courier; your efforts were much appreciated as well. Thank you to the following for granting permission to use your photo(s) or research materials: The Avery Research Center, College of Charleston, SC, the Post and Courier, the Charlotte Observer, the News and Record/the Greensboro Daily News, Smith Studio (Photographers), Julia Adams, Virginia Parker Collier, Monika Engelken Stuhr, Katherine Groves Williams, Cecil Williams, Millicent Brown, Harvey Gantt, Larry Canady and Kristina Frazier. Every effort has been made to secure permission to use any copyrighted material. If you are a rights holder and feel that your material has been used without proper permission, please contact the publisher.

Thank you to Dr. William Hart for sharing your expertise during the early stages of my research and thank you to Dr. john a. powell for sharing your expertise in the latter stages. I acknowledge Monica Walker for broadening my understanding of implicit bias as her trainings provided me the opportunity to attend sessions by, personally meet and later interview Dr. john powell. Thank you to Peter Byrd (Grimsley High School Historian) for his attention to detail and willingness to share his expansive knowledge about the history of Greensboro (Grimsley) Senior High School. Thank you to Richard Greggory Johnson ← xii | xiii → and Dr. Deborah Davis—your encouraging words and editing expertise were greatly appreciated. To Richard Allen, I found you in the nick of time; thank you for editing both my dissertation and my book. A huge thank you to Michael Gurian for writing the Foreword; your research and books are transformative. I only hope that my research and text are as influential, inspiring, and transformative as yours.

Last, but not least, I am forever grateful to Josephine Boyd Bradley, Millicent E. Brown, Harvey B. Gantt, Dr. Larry Canady, and Kristina Frazier. I acknowledge the family of Dr. Boyd Bradley and am grateful for the ongoing friendship of Dr. Larry Canady—you are one of the most intelligent and upstanding people I know. I am confident that your wife, family, and especially your grandmother are extremely proud of you. Thank you to Rebecca Gibson; you were truly a godsend. I know our paths were connected for a reason and your assistance and belief in my work helped to transform my manuscript into the book you see before you, Pedagogy of Survival. ← xiii | xiv → ← xiv | xv →

Karen Meadows is a dynamo of energy and acumen. As she gathered these stories, she had a vision in mind: to link the power of personal narrative with the strength of the human spirit. Pedagogy of Survival has emerged from that vision, and I am grateful for it. I know you will be, too. As I read the narratives and counternarratives in this book, I find myself reflecting on issues of personal responsibility and expanding my vision on many points of view in an area of life too minimally studied thus far, the social and human agency of adolescents and young adults who comprised a powerful cadre of desegregation pioneers in the 1950s and 1960s.

These were survivors and their lives developed pedagogy at inchoate levels. Dr. Meadows shows us these internalized methodologies through her inclusion of (1) the Story, (2) the Trauma, and (3) the Pedagogy of Survival. Through their eyes and lenses, we understand and address ongoing educational discourses concerning academic and disciplinary disproportionality in our public schools. The interviews with Harvey B. Gantt, Dr. Larry Canady, and Kristina Frazier, in particular, reveal diverse ways in which an individual models and teaches his or her own method of survival.

Our adolescents today—especially those locked in melancholy and violence—hunger for these models. As adolescent life becomes more dis ← xv | xvi → tended in the new millennium for many youth and, for some, more truncated by early death, the hunger to identify with others who have struggled is an existential condition of our age. The author’s incorporation of reflective questions throughout the book is masterful: it requires readers to examine their own lives and the impact of their lives on others. Our youth need this reflection, in print, in story. Though our present-day media seems to present young people as constantly ironic, our youth are also deep thinkers. They carefully puzzle out the world even if they don’t always let us know what they are thinking. Dr. Meadows helps them (and us) by asking questions that can lead to good answers:

“How do we create opportunities for learning that will be accessible to students of varied backgrounds or circumstances?”

“How do we promote equity in a society and system permeated with a legacy of inequitable practices?”

“How do we inspire others to persevere, be empathetic, see their own capabilities, and move beyond individual and societal biases?”

These questions speak to the importance of including in our canon the ordinary people in our history who live out extraordinary lessons. As good books do, Pedagogy of Survival helps us find our answers to life-questions through the greatness and the humility of human stories. Each one teaches character and principles of social justice, and locates paths to a sense of life-purpose. Every young person, if left alone to talk frankly with someone he or she loves, will yearn to move from exhaustion or frenzy or shame or pain to “How did I make a difference?”

Youth in previous generations have endured and navigated traumatic experiences and been humanized by them—that humanity shaped purpose for them and can do so now for some of our youngest change agents. It is in this context that we read of the activism of a father, the determination of a woman, the struggles of a black man, the mentorship of a teacher, the belief of a grandmother, and the love of a mother—each changed the trajectory of young lives. Every youth wonders, “Who am I?” Answers come from struggle. Pedagogy that grows from suffering and ordeal is often its most trustworthy signpost.

If you are an educator at the secondary or collegiate level, I believe you will find this book a worthy supplemental text in related fields. If you are an administrator, parent, grandparent, or other mentor of youth, this book is a powerful way to learn and to teach. If you are tasked in any way with teaching character traits—courage, sacrifice, integrity, and resilience—this book will ← xvi | xvii → be useful and inspiring to you. As you reflect on these stories, I believe you can’t avoid wondering what your own blueprint for these traits is and can be.

Dr. Meadows tells us, “The circumstances in our lives matter; our acts of courage matter; our perseverance matters; our personal knowledge matters; and our story matters.” All indeed matter a great deal, and they are intertwined in a story of human struggle that is the bedrock of a free society.

Without story, we can live in illusion; intimate with story, we know who we are. ← xvii | xviii → ← xviii | xix →

It was a brisk autumn day and I’d made my usual “good morning” phone call to my mother. She did not answer, so I knew she would call me back as soon as my message was received. As I went about my morning routines, drinking a cup of coffee and preparing for work, my call still had not been returned. So I adjusted my preparation time; I thought, I’ll just stop by on my way to the office. Exercising my courtesy knock as I always did before using my key, I waited but there was no answer. I thought, perhaps she’s taking a walk. I’ll leave her a note and call back later (cell phones were not a household staple at this time, so there was no calling while en route to work). Opening the door, I called out, “Ma, Ma,” but there was no answer. I saw her glasses on the arm of the chair. That meant she must be at home. In utter confusion, I made my way through the house. My heart was racing. What is going on? What is happening? Still confused, I found her.

Details

- Pages

- XXVI, 214

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433131578

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433137587

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433137594

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453916919

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433131585

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1691-9

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (August)

- Keywords

- existentialism implicit bias organic intellectual pedagogy of survival trauma qualitative narrative research school desegregation Harvey B. Gantt Millicent E. Brown Josephine Boyd

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2016. XXVI, 214 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG